Douglas Barrowman describes himself as an “entrepreneur”. The reality is that his businesses made a fortune mis-selling tax avoidance schemes on an industrial scale to people on modest incomes. The schemes all failed, leaving their clients with huge tax bills – many went bankrupt; at least two killed themselves. The clients were then directed to a new company – Vanquish – with a new scheme that supposedly could make those tax bills disappear. That scheme was legally hopeless and relied upon false documents – we believe those involved should be prosecuted for tax fraud. And, whilst Barrowman has denied any connection to Vanquish, the evidence suggests he is lying.

The Times first reported on Vanquish in 2019. BBC File on Four carried a further, more detailed report in 2020. We’ve used these reports as a starting point, and obtained significant amounts of additional documentation and correspondence from AML’s former clients. That new evidence, plus the expertise of the tax specialists we work with, enables us to reach new conclusions.

We believe that the evidence shows that the AML and Vanquish schemes were fraudulent, that the Vanquish schemes relied upon a false document signed by key Barrowman personnel, and that Barrowman’s denial of any connection to Vanquish was a lie. Whether the criminal offences of fraud or tax evasion were actually committed are questions of fact, which ultimately a jury would have to decide, but we believe there is sufficient evidence for a prosecution.

To understand the nature of that evidence, we have to go back through some of the history. This report is therefore inevitably somewhat lengthy.1We nevertheless cover only a very small part of the history – a big omission is IR35. Anyone interested in the full background should start with the Morse Review

Contents

- Loan schemes – the history

- Barrowman’s AML Tax business

- The 2019 loan charge

- AML’s first response to the loan charge

- The Vanquish scheme

- The false documents

- How responsible is Douglas Barrowman?

- How much money did Barrowman make from the schemes?

- Evidence for a prosecution

- Why prosecute?

- Barrowman’s response

Loan schemes – the history

There’s an obvious way to avoid tax on your income: replace it with a loan. Income is taxable; a loan isn’t. If you turn £80,000 of salary into a loan you’ll save £33,600 (40% income tax, 2% employee’s NIC).2We’ll ignore the personal allowance to make the calculation easier

But the equally obvious problem is: you’ll have to repay the loan. This problem was solved in the 1980s3One of the key originators of the scheme was Paul Baxendale-Walker – a barrister and solicitor who moonlit as a porn star, and eventually ended up struck off, bankrupt, and convicted of fraud. It’s very strange that someone so peculiar was responsible for so much damage to the tax system, to many peoples’ lives, and led to the downfall of a football team. There’s a good summary of much of this in the Wikipedia article on Baxendale-Walker, but be warned that the article is out of date and parts of it appear to have been written by him. with the invention of the offshore employee benefit trust (EBT). The idea was that if (for example) you normally earned £90,000, then £10,000 of that would be paid normally, but your employer would pay the other £80,000 to the EBT. The EBT would lend you £70,000 of it, saving you £23,600 each year, and retaining £10,000 as a fee. The claim was that the nature of the trust meant that the trustee wouldn’t, and perhaps even couldn’t, demand repayment of the loan. So the promise (rarely put in writing) was that the “loan” was a very funny kind of loan which would never be repaid, and would remain in existence forever.

In our view these schemes never worked – the uncommercial nature of the loan meant that it wasn’t a loan at all – it was simply remuneration, taxable in the usual way. HMRC was, however, slow to challenge the schemes, and they became widely adopted by large corporates. Eventually, in 2000, HMRC started a challenge against Dextra, a scheme used by John Caudwell, the founder of Phones4U.4Interestingly, in 2022 John Caudwell said he was “extremely proud” of paying tax in the UK and “absolutely wouldn’t” use loopholes to save money again. Caudwell and colleagues had avoided tax on about £17m of income,5See paragraph 18 of the case here but the significance of the case was much wider than that. So it was unfortunate that HMRC lost – the failure of the court6The old Special Commissioners, who heard first instance tax appeals until the modern tax tribunal system was adopted in 2009 to step back and look at the reality of what was going on looks very wrong in retrospect.7HMRC did appeal on the question of whether the company was entitled to a deduction for its payment to the EBT, but didn’t appeal on the question of whether the individuals should be taxed on the loan amounts.

The Government’s response was to change the law (but only somewhat). That was insufficient – Dextra was seen as a green light by promoters of the scheme, who just slightly adapted their schemes to (they claimed) get around the new laws. The Revenue lost more cases, the law changed a bit more and the promoters responded by tweaking their schemes again. This “arms race” between Revenue and promoters continued for years, so in the last twenty years we have had eighteen different versions of the “employee benefit contributions” tax rules.8See e.g. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/14/schedule/23 and https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/4/part/20/chapter/1/crossheading/employee-benefit-contributions.

In 2004, the Government warned that future game-playing would result in retrospective legislation. Retrospective legislation duly followed in 2006, but only a subset of schemes were targeted. From that point, it became standard practice for law firms issuing opinions on tax matters9i.e. mundane vanilla transactions, not tax-motivated transaction, as by that time major law firms would rarely if ever advise on tax avoidance arrangements to add a caveat that retrospective legislation was a possibility. However we are not aware of any promoters of loan schemes ever warning about retrospection risk (or indeed of any risk).

HMRC lost another case – Sempra – in 2008. Again, it wasn’t appealed. To be fair to HMRC, at this point the courts seemed to be refusing to look at the “loans” realistically, which was peculiar given that in other contexts tax avoidance schemes were being merrily struck down where elements were artificial.10As late as 2014, the First Tier Tax Tribunal (FTT) and (on appeal) Upper Tier Tribunal (UTT) found for the taxpayer in Murray Group Holdings (the Rangers case) on the basis that the repayment of the loans was not a “remote contingency”. This showed a remarkable failure by the tribunals to understand what was going on – these structures only make commercial sense if the loans aren’t repaid. The “loans” are, in reality, not loans at all.

These failures and half-measures just emboldened the promoters.

In 2010, the Government finally stopped fiddling with the details of the legislation, and introduced a broad anti-avoidance rule specifically designed to stop all the variants of the loan schemes – the “disguised remuneration” rules. As tax barrister Patrick Cannon says, it was clear from that point (at least to advisers) that anyone engaging in a disguised remuneration scheme would be acting contrary to the intention of Parliament, and that rarely ends well.

Large corporates and banks generally received sensible advice from specialists like Mr Cannon, and ended their loan schemes. But individual self employed contractors, typically working through their own services company or another intermediary, and earning relatively modest incomes, didn’t have the benefit of any of this advice. That created a huge opportunity for unscrupulous promoters, who could market schemes to individual contractors which supposedly got round the disguised remuneration rules, take highly aggressive positions, collect large fees, but suffer little or no downside if (as was always likely) the schemes failed to work.

Barrowman’s business, AML (UK) Tax Limited, had started up in 200911Although other AML entities appear to have started to run schemes as early as 2006 – it was not in the least bit deterred by the new legislation.

Barrowman’s AML Tax business

Here’s their pitch – on the face of it’s exactly the EBT loan scheme we summarised above:12Barrowman had numerous companies selling what was always basically the same scheme. This video is badged “Principal Contractors”. A lawyer looking at their emails and website immediately sees something odd: no company name is ever stated, just “Principal Contractors”. We can find no evidence that company ever existed. However “Principal Contractors” is registered in the Isle of Man as a “business name” of Principal Contracts Limited, one of Barrowman’s companies. We can also tie Barrowman directly to documents sent out by Principal Contractors.

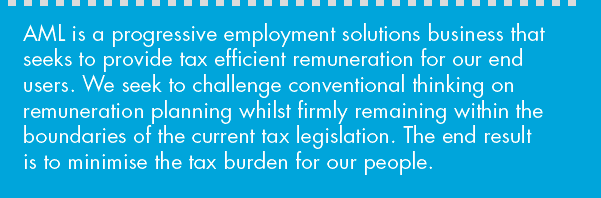

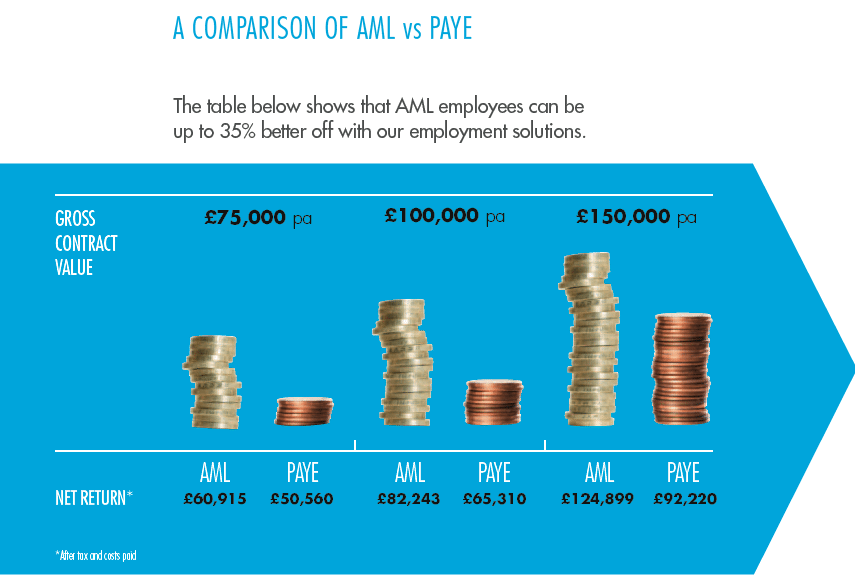

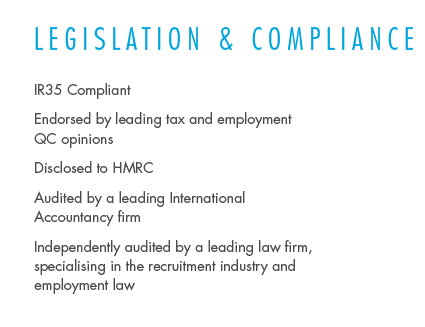

There’s more detail in AML Tax’s brochures (full PDF copy here).

Words that are missing: “loan”, “offshore”, “avoidance”, “risk”, “retrospective”.

And the following promises were made:

The marketing of these schemes appears to be false and deceptive in a number of respects:

- Were the schemes really endorsed by a leading tax QC? We’ll probably never know. But even if they were, the opinions almost certainly provided no actual comfort to clients – we explained why here.

- Was the scheme really “audited by a leading international accountancy firm”? Or was the only audit the standard audit of AML’s own accounts?

- Where is the warning that the scheme creates a loan which is legally required to be repaid? We have reviewed the AML loan documentation, and it enables the lender to demand repayment, with no protection for the borrower – and that has recently had terrible consequences for some of AML’s clients. However the clients were, so far as we are aware, never warned of this. The assurances that the loan would never have to be repaid were critical to the scheme (because otherwise who would accept it?) but false.

- Where is the warning that the Government had already threatened retrospective legislation to reverse remuneration tax avoidance, and had actually done so on one recent occasion? This was known to all competent advisers. But, as far as we are aware, AML never mentioned it to their clients – and the fact retrospective legislation was even technically possible came as a shock to most of them when (as we’ll come to shortly) the Government used exactly that route.

- The “disclosed to HMRC” line is particularly troubling. There is usually only one way a structure gets disclosed to HMRC – under the “disclosure of tax avoidance schemes” (DOTAS) rules.13The point being to identify avoidance structures early to “inform legislation to close loopholes” (see e.g. paragraph 2.2. here Early iterations of the AML structure were disclosed to HMRC, later iterations weren’t.14AML has twice been found by a court to have unlawfully failed to disclose under DOTAS; those schemes were slightly different, but we believe all were disclosable. We’ve reviewed a email explaining AML’s basis for not disclosing under DOTAS in 2015, and in our view it’s clear AML was acting unlawfully. We even have an email from Arthur Lancaster (an AML director) using the lack of DOTAS disclosure as a selling point.15In theory the structure could have been disclosed on some informal basis, but that would be contrary to HMRC’s usual practice. Another possibility is that elements of the scheme were individually disclosed in response to preliminary HMRC enquiries. But we would very much doubt the whole scheme was confirmed, outside DOTAS. So why did this brochure claim the opposite?

- Contractors were assured in emails that the trustees who’d be making their loan were “independent”. In fact, all the trustees we’re aware of were companies in Barrowman’s group. We’ve more about the trustees later.

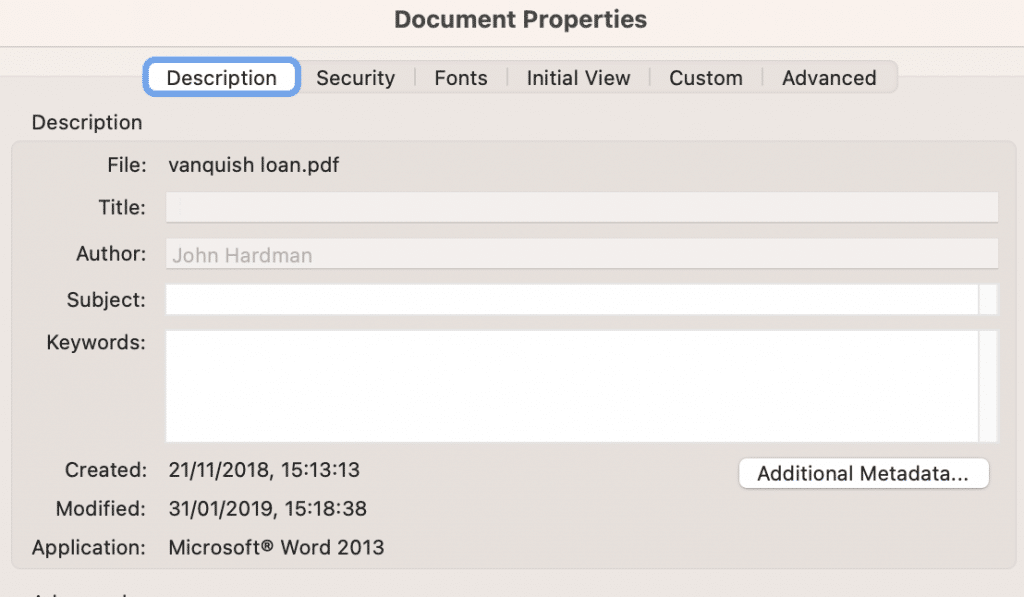

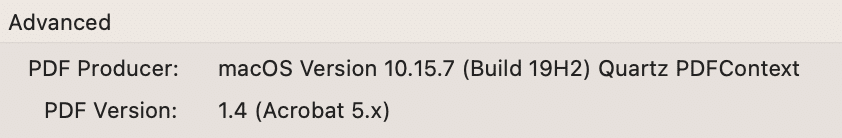

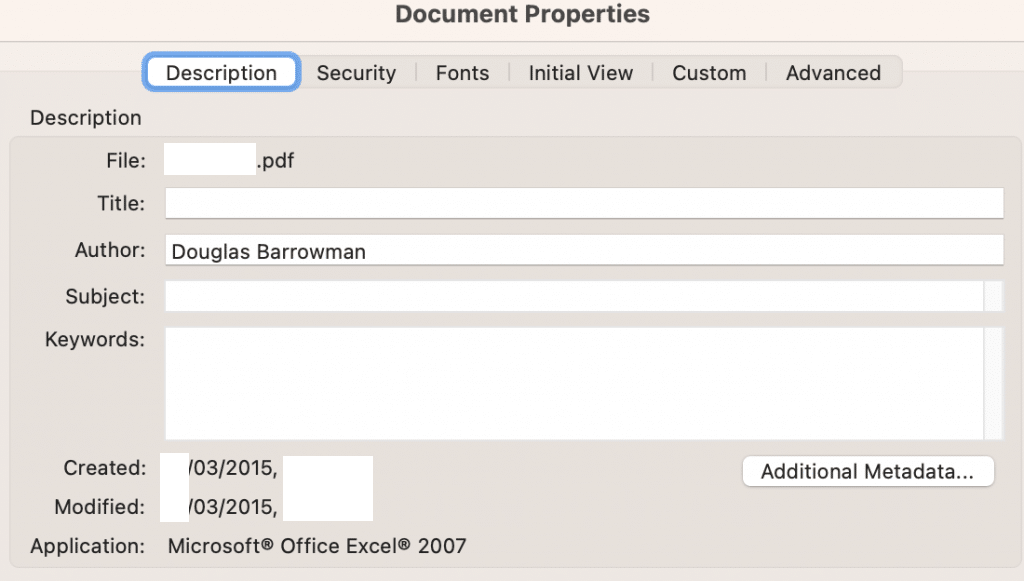

- And who, really, was running this scheme? Were there appropriately qualified people advising on the tax and drafting the documents? We don’t know who provided the tax advice, but metadata16Metadata is the hidden information contained in computer document files. For example, if you open a PDF document in Adobe Acrobat, then click “File” and “Properties”, you will see the author of the document (or at least the person whose details were entered into the application that generated the original document) and the details of the application that generated the PDF in the loan documentation indicates who drafted it – John Hardman: a former solicitor, struck off for dishonesty, who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser. There were various different lenders over the years; all the documents we’ve reviewed which have author metadata show Hardman, or his firm (“HC Legal Consulting“) as the author. 17Metadata needs to be viewed with caution. It can be changed, although here that would mean multiple former AML clients sent us documents with identically forged metadata, before they even knew we were looking at metadata (or, in many cases, before they knew that metadata existed). That is therefore very unlikely. More importantly, metadata does not tell you who wrote a document. The default setting is that the “author” is taken from the user of the machine on which the PDF was created, but this default can be changed. Someone else could be using that person’s computer. If we had one loan document with Hardman in the author metadata then that could easily be an accident, but multiple documents created over years for different lender entities, sent to us by unrelated people, is much less easy to dismiss.

- Contractors were also assured that AML “employed its own in-house barrister”. As far as we are aware, AML never employed any barristers; the only legally qualified individual we’re aware of was John Hardman.

- There was no warning at all about the risks that the scheme was running. As the Chartered Institute of Taxation (CIOT) put it, loan schemes, whilst not illegal, were contrived avoidance schemes which were always likely to be robustly challenged by HMRC.

- Nor was there any warning that if HMRC successfully challenged the schemes, or if there was a retrospective change of law, contractors could be solely responsible for paying the tax. The contractors we’ve spoken to had no idea this was the case – they assumed that AML would be responsible.

- The failure to outline the risk, and who would be responsible if it crystallised, was in our view critical to the contractors agreeing to the scheme – we believe that, if it had been outlined, few if any would have signed up to it. And we believe the people marketing the AML scheme knew that.

The 2019 loan charge

HMRC could have aggressively challenged all of the contractor loan schemes using the disguised remuneration legislation, and made clear public statements (aimed at contractors, not advisers) that the schemes didn’t work. They didn’t do either of these things.18There was a Spotlight published in 2015, updated/replaced in 2016, but by then it was too late. Contractors would readily believe promoters who responded by claiming that their scheme was totally different from the Spotlight scheme, and the lack of HMRC challenge proved this. The industry probably could have been strangled at birth: it wasn’t.

It’s unclear why HMRC did not react more aggressively. It may have been chastened by the judgments against it. Possibly HMRC did not appreciate quite how many people were now using the schemes.19The schemes were not disclosed on tax returns but there were fairly obvious tell-tale signs: the sudden 90% drop in reported income, and the use of AML affiliates as the accountants submitting the tax return; query how fair it is to expect HMRC to have spotted this at the time. But, regardless of the reason, by the mid-2010s there were around 67,000 users – the true number may be higher. Many were under HMRC enquiry (i.e. a formal tax investigation); many were not. When HMRC did open an enquiry, promoters often took control of correspondence and sent back obstructive replies. This, combined with the huge scale, made conventional HMRC challenges difficult and perhaps impossible.

One option would have been to change the law going forwards to put beyond all doubt that the schemes didn’t work. But it was highly likely the promoters would ignore any new rule in exactly the same way as they’d ignored the old rules.20As indeed happened – see Smartpay below It meant HMRC would have to continue with the very difficult large-scale enquiry process. And there would be a big revenue loss from all the existing schemes that were not already under enquiry – well over £3bn.

The situation was out of control.

So HMRC and HM Treasury did something quite different: a return to the old tactic of retrospective legislation, but this time with much more impact. They created a one-off tax in 2019 for all loans made since 1999. People would have three years to repay the loans. If they were normal loans (like a standard season ticket loan) people would repay them and there would be no tax. But if the loans were really disguised salary then the loans would remain, and would be taxed.

Now imagine you took part in these schemes. You’ve been borrowing £70,000 a year for each of the last ten years. Perhaps HMRC has never opened an enquiry; perhaps they have but the promoter never told you; perhaps the promoter told you, but seemed confident HMRC would go away.

Now you’re facing a tax hit – the “loan charge”. £70,000 x 10 x 45% = £315,000 of tax. How are you going to pay that? HMRC will give you time to pay the tax – but you can’t afford it. Repaying the loan would eliminate the tax, but that requires an even-more-impossible £700,000 (plus interest). This retrospection was highly controversial and was described by the CIOT as a “blunt instrument“.

This might feel just if (in our example) the £315k just took you back to where you would have been if you hadn’t bought into the scheme. But it’s worse than that, because AML extracted their 16% fee, and you won’t be getting that back. You end up in a much worse position than if you’d never bought into the scheme at all. And of course, who earning £70k/year can afford a lump sum £315k payment?

This caused, and continues to cause, terrible financial and personal consequences for AML’s former clients. HMRC were warned about the hardship the loan charge would cause some people back in 2016, and the risk to mental health and even suicide was mentioned; but momentum had built up, and it was clear that the loan charge was coming regardless of opposition. To be fair to HMRC, by that point there were no good options – the mistakes of the past could not be fixed.

What would have happened if, instead of the loan charge, HMRC had properly pursued the schemes in the early 2010s, before they spiralled out of control? Many scheme users would have been put in equally dire financial straits. Escaping tax on all of your income inevitably creates a very large liability if the tax scheme fails, which most people will not be able to afford to pay.21Which is why we believe no reasonably prudent adviser would ever advise someone on a relatively modest income to use a scheme of this type, even if it had good prospects of success But earlier HMRC action could have reduced the numbers involved, and the number of years’ tax at stake.

This report won’t go into the rights and wrongs of the loan charge, and HMRC’s actions (and lack of action). Many AML clients/victims are understandably furious with HMRC. It is, however, our belief that primary responsibility rests with AML, and the others promoting and profiting from the schemes. At least two Barrowman/AML clients have killed themselves22Our source for this is the Loan Charge Action Group, who have identified that two of the reported cases of suicide were of former AML clients: moral responsibility for that is on AML and Barrowman. It is their involvement that is the focus of this report.

AML’s first response to the loan charge

The loan charge was announced in April 2016. At that point it was clear to all that the loan schemes were dead, and the only effect of advancing additional loans was to increase the contractors’ liability.

But additional loans would also mean additional fees for Barrowman’s group. So the loans continued.

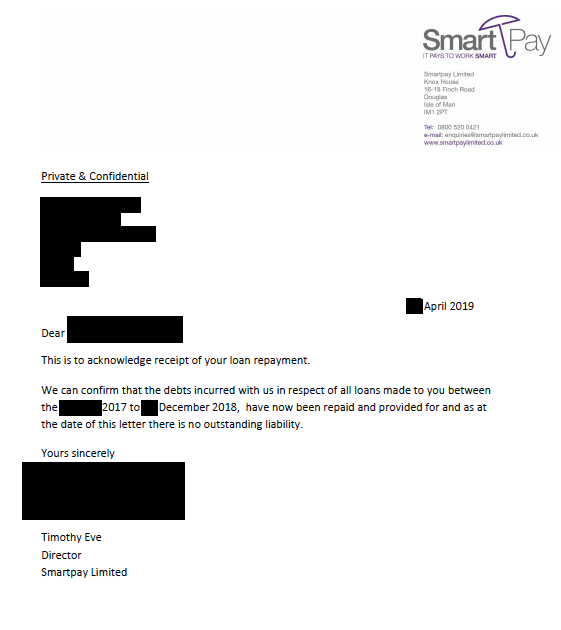

Astonishingly, we have evidence that Barrowman’s companies continued with the loan schemes until as late as December 2018, two-and-a-half years after the loan charge had been announced. We cannot understand how anyone would have regarded this as appropriate. In our view it approaches, and may have been, fraud.

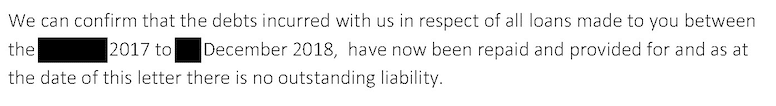

This is a serious allegation to make, so we feel it is right we present the evidence. This is a letter from Smartpay Limited, signed by the Deputy Chairman of Knox (Barrowman’s business), showing they continued to make loans right up to December 2018:23We are redacting the details to protect our source.

The letter was sent as part of AML’s other post-loan charge plan – to create another scheme that it claimed would rescue its clients from the loan charge. That was Vanquish.

The Vanquish scheme

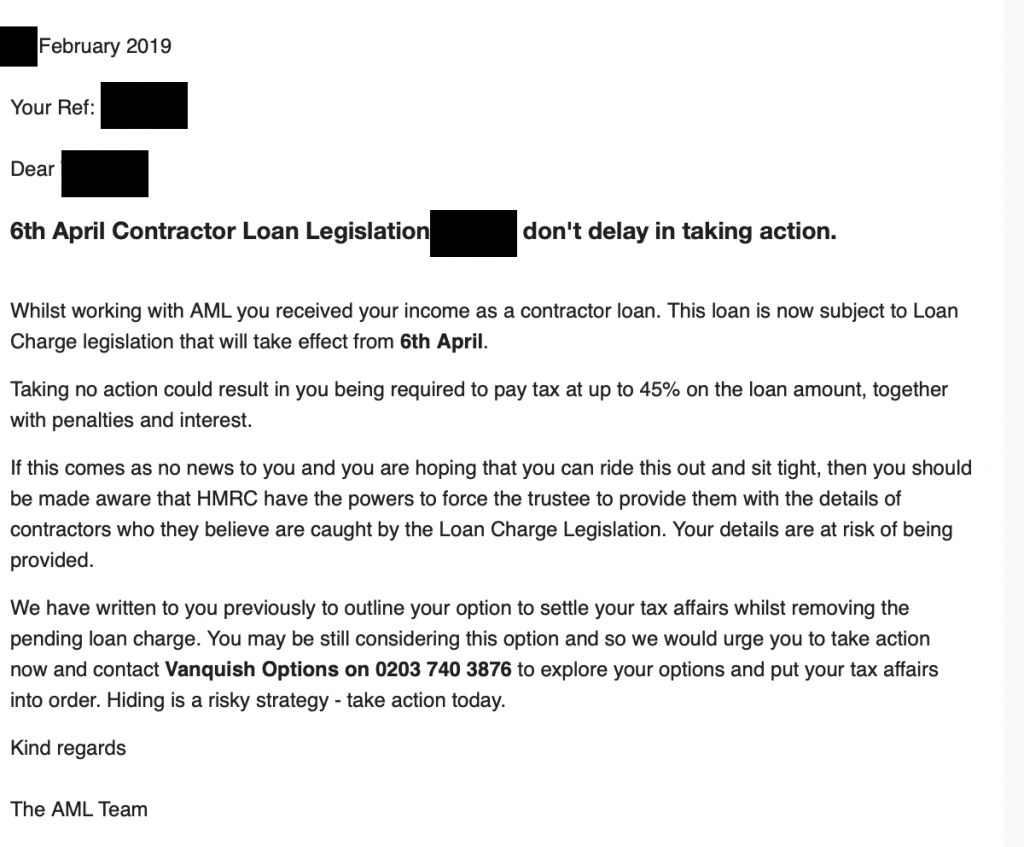

AML and the other related Barrowman companies ceased trading around the time the loan charge came in. They sent their former clients an email like this:

Vanquish also had a website.24This and many other links in this report are to the “Internet Archive“, which enables us to view websites as at particular dates in the past, even if they no longer exist. Note that many corporate networks block the Internet Archive (because it could otherwise let users circumvent restrictions on which websites they can view), so you may need to view these links on a mobile or home computer.

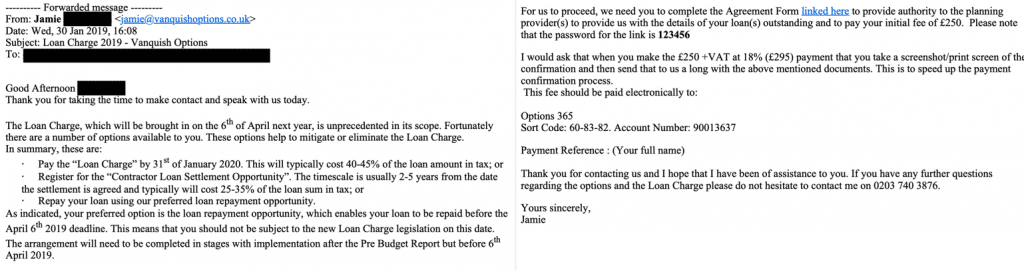

When asked what precisely their “option” involved, Vanquish were reluctant to spell out the details.25See this forum post – there are many others like it They described it as a “preferred loan repayment opportunity” which would mean that the contractor would “not be subject to the new Loan Charge legislation”. Payment should be made to a mysterious new Malta entity, Options 365:26We would not normally include publish bank account details, but the same information has been visible in forum postings for four years; furthermore there is a chance this information will be helpful to other researchers.

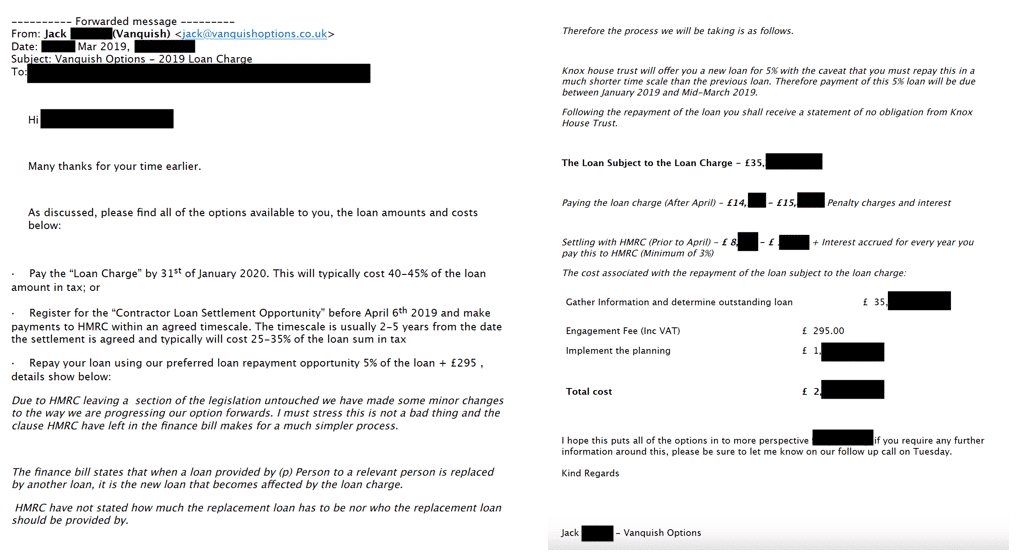

People kept pressing, and eventually they were able to extract some details from Vanquish. The “preferred repayment opportunity” turned out to involve taking another small loan to pay back the original large loan27See this forum post. That doesn’t make much sense, so people who agreed to proceed were given a more detailed explanation – here from “Jack”:28We have not been able to positively identify Jack or any of the other individuals appearing in the Vanquish emails we have reviewed. This is surprising given that most people working in marketing, tax, accounting and business development are on LinkedIn. One possibility is that these were assumed names. We are not publishing the full names, because of the potential for innocent people to be wrongly identified (if the names are false) and the potential for junior employees to be unfairly blamed (if the names are real).

Thanks to File on Four we have the benefit of a recorded telephone call with one of Jack’s colleagues, “Jamie”.29See the File on Four transcript – paragraph 16 Putting all of this together, the Vanquish structure looks like this:

- The EBT will split your loan into a 5% and a 95% bit.

- You’ll then repay the 5%, bringing its balance to zero.

- The 5% is then invested into a third-party investment company.

- The third-party investment company takes on the remaining 95% loan.

- The 95% loan would not be written off because that would trigger a tax charge.

- But the 95% loan is no longer your problem – you won’t have to repay it, and you won’t have to pay the April 2019 loan charge.

So on our example numbers above: you owe £700,000. The loan is split into £35,000 and £665,000 sections. You repay £35,000 and the £665,000 disappears, with no loan charge.

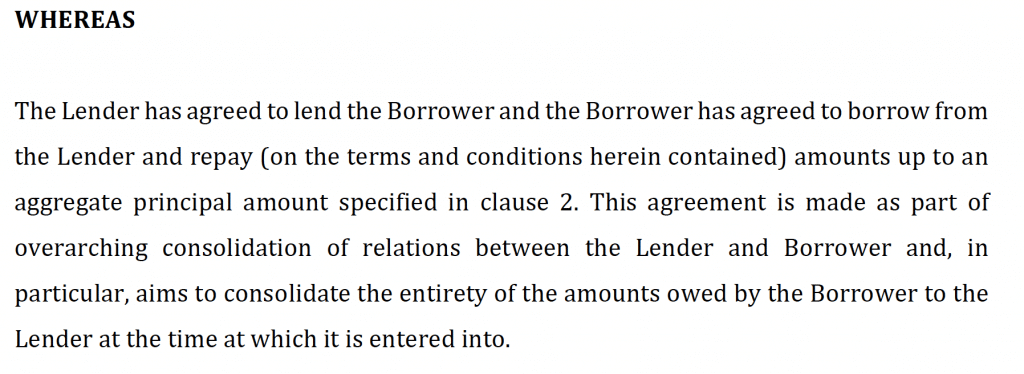

But this isn’t what actually happened. Here are the documents Vanquish’s clients were given (PDF version here):30When we first received Vanquish documents from a contractor we assumed that he had mislaid the document moving the loan to the third-party investment company. However when we received more sets of documents, we were still missing any document referring to the investment company. We spoke to advisers representing former Vanquish clients, and they’d had the same experience. We’ve also reviewed HMRC correspondence sent to former Vanquish clients, and it is apparent HMRC have also never seen any documents relating to a third party-investment company. A review of forum postings suggest that by early 2019 the scheme had changed. It is therefore our conclusion, as well as that of the advisers we spoke to, that Vanquish never implemented the “Jamie” structure.30Could the structure still have been implemented behind the scenes, with the lender entering into some kind of agreement with the third-party investment company? We think not, or at least not in a legally coherent manner. As a legal matter it’s not possible for the borrower’s side of a loan to be transferred (“novated”) to a company without the borrower signing a legal agreement (there is a nice explanation of novation from law firm Watson Farley Williams here).

All these documents do is:

- Supposedly grant a new loan of the 5%, from the same lender (“to consolidate” the previous loan, which is nonsense). Contrary to the description by Jamie, it’s not a split of the original loan at all – it is (at least on its face) a new loan. But it’s a very curious loan, because no money is advanced by the “lender” to the contractor under this document. It’s not really a loan at all.

- Create a “statement of no liability” – a letter saying that the original loan has been “repaid and provided for”. We don’t know what “repaid and provided for” is supposed to mean, but the original loan (£700,000 on our figures) certainly wasn’t repaid by the client.

- What the documents don’t say, but what happens, is that the new 5% “loan” is repaid soon after it’s granted. The contractor never received the 5% from the lender, but they make a “repayment” of that 5% anyway. The “statement of no liability” then is issued. So the “loan repayment” is more realistically a fee, in return for which the contractor gets the “statement of no liability” to show to HMRC that the loan doesn’t exist.

How could this work? Jack’s email mentions paragraph 2 of the loan charge rules. This says that, when an old loan is replaced by a new replacement loan, then the April 2019 loan charge applies to the replacement loan. It seems Vanquish think that if the original loan was £700,000, but the replacement loan is for £35,000 then that £35,000 is all that’s taxed under the April 2019 loan charge rules (and if the £35,000 is repaid then there is no loan charge at all). That would be a wonderful result for the client. It is, however, indefensible as a matter of tax law:

- For a start, as we say above, the “new loan” isn’t really a loan at all – realistically it’s just a fee for entering into a tax avoidance scheme to avoid the loan charge.

- But if paragraph 2 does treat the new “loan” as a loan then the effect is that, for the purposes of paragraph 1, the replacement loan is deemed to be the original loan. That means that the replacement loan is brought into the April 2019 loan charge. But the amount taxed isn’t the £35,000 amount of the replacement loan – it’s the original £700,000 lent.31Because the charge is based on the amount that is “outstanding” on 5 April 2019. The term “outstanding” is defined in paragraph 3 as the “initial principal amount lent” (with some adjustments, including for amounts have really been repaid). This is not defined further but has nothing to do with the amount of the replacement loan and so would not change the amount taxed in April 2019. In other words, replacing a loan for £700k with a loan for £35k doesn’t change the fact that the amount initially lent was £700k, and so doesn’t change the tax charge. The scheme fails.32This was a failure common to a number of loan charge avoidance schemes. The leading practitioners’ textbook, Pett on Disguised Remuneration and the Loan Charge says that none of the loan charge avoidance schemes addressed this point, and follows this with a statement that criminal charges had been brought against a number of individuals in connection with the such schemes – see para 15.6.

- However the scheme does worse than fail. There’s a specific tax charge if someone “releases or writes off” a loan under the normal disguised remuneration rules (and perhaps under the normal rules for beneficial loans and general earnings charge as well). Jamie seems to think there isn’t a problem because the £665,000 now owed by the investment company is never released. The final structure doesn’t appear to have actually worked like that, as we can’t find evidence there was ever an investment company, but even if there was one behind the scenes, Jamie’s claim is false. The question is whether the £665,000 you owed was released – and clearly it was. You previously owed £665,000, and now you don’t. That’s a release, no matter how you describe it or dress it up.33As a matter of English law and UK tax law you can assign the lender’s side of a loan, but you cannot assign the borrower’s liability. Anything that looks like the borrower is moving their liability to someone else is actually a release of the old debt and the creation of a new debt – often called a “novation“. The courts have always been clear on this. So the scheme doesn’t just fail to eliminate the loan charge, it triggers an additional 95% liability on the release.

- It then gets worse still. There is a targeted anti-avoidance rule (“TAAR”) in paragraph 4 that says that a payment (e.g. the repayment of the 5% loan) is to be ignored if there is any connection (direct or indirect) between the payment and a tax avoidance arrangement. Vanquish is, needless to say, a tax avoidance arrangement. So even though the new 5% loan might actually be repaid, it is still outstanding for the purposes of the loan charge and tax would still be due. That’s an additional 5% liability. The repayment of the 5% achieves nothing except giving money to Vanquish. We don’t understand how anyone could think the TAAR wouldn’t apply.

- There is also a General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR) which HMRC can apply to defeat schemes. The question then is whether entering into an artificial arrangement to defeat an anti-avoidance rule is a reasonable thing to do, when it involves artificially splitting a loan into two and somehow transferring 95% of the borrower’s liability to a random company solely for a tax avoidance purpose. Or, in the actually implemented version of the structure, whether pretending to “consolidate” a loan and then magicking the 95% away behind the scenes is a reasonable thing to do. Neither sounds reasonable to us. Contrived disguised remuneration schemes have been considered by the GAAR Advisory Panel many times, and failed each time. There is no reason to expect a different result here. The loan charge tax would be due and, in addition, the individual could be landed with a GAAR penalty of 60% on top.

- All of this means that a client buying the Vanquish scheme would incur multiple tax charges, including (but not limited to) the original loan scheme charge, a disguised remuneration charge on the new loan, and a charge on the release of the old loan. The liability could more than double. 34In practice HMRC doesn’t appear to take these points, but we believe technically multiple charges do apply (there are others in addition to those mentioned in this paragraph).

- It was clear that HMRC would contest the scheme – only days earlier it had published a “Spotlight” (a public notification highlighting common tax avoidance schemes) saying that these kind of attempts to avoid the loan charge wouldn’t work.

In our opinion any reasonable adviser, even a non-specialist, would have known that the Vanquish structure would be challenged by HMRC, and that the structure would fail. This goes beyond normal negligence. Proceeding in the teeth of the HMRC Spotlight looks like madness.

But actually it made absolute sense for Vanquish, because (on our numbers) it made £35,000 in fees and took no risk. Vanquish then ceased trading soon after the loan charge kicked in. And, of course, HMRC did contest the structure, using some of the arguments above.

Clients buying the Vanquish scheme were asked to sign a letter authorising the transaction to proceed. But the letters weren’t with Vanquish35There is an ancillary question as to whether Vanquish itself has properly accounted for corporation tax on its profits. It was introducing clients to a variety of offshore companies who were charging large fees; however from Vanquish’s accounts it appears as though Vanquish received no compensation for this. That is not the result one would expect. – they were with the mysterious Maltese company, Options 365 Limited (which File on Four found was held by Barrowman’s Knox Group.36see page 17 of the transcript).

The false documents

The whole point of the Vanquish scheme was to make the loans disappear, and so eliminate the loan charge. That required something contractors could give to HMRC as evidence that the loan had been repaid. This was the “statement of no liability” (the last document in the above gallery and also this PDF).

The key paragraph is this:

This statement is a lie: the loans had not been repaid.37The document says “repaid and provided for”. This is curious terminology. If a loan is “provided for” that usually means that the lender thinks it won’t be repaid, and so has written it off in its accounts, even though it remains in existence as a legal matter. “Repaid and provided for” is a non-sequitur. Possibly the authors thought this gave them sufficient cover to avoid any suggestion of fraud. It does not. The document says the loan was repaid, and it wasn’t. The other potential argument the authors might raise is that the loan was repaid, just not by the contractor. That may have happened (one can imagine a circular movements of funds behind the scenes, not involving the contractor at all), but it is not what most ordinary people would understand by the word “repaid”. And that ordinary meaning of “repaid” is expressly adopted by the loan charge legislation, which says a repayment must be a “payment in money” by the contractor. We don’t believe the authors of the letter can credibly claim that “repaid” was intended to have a meaning which both defies common sense and the legislation that the letter was created to thwart. This is a false document.

As we note above, the new 5% loan created by the Vanquish structure is not really a loan at all. This is what the Vanquish loan says is happening:

…

But this isn’t true – in no sense does the Borrower receive a loan advance from the lender.38It is of course not necessary for a borrower to actually receive cash themselves – for example in a typical mortgage, a person is borrowing to finance the purchase of a house, but the loan goes straight to the seller (via the solicitor) and the money is never received by the borrower. There is however no doubt that in that case the borrower is receiving the benefit of the loan advance, both in practical terms and legal terms – the way the money moves is a point of detail. By contrast, in Vanquish there is no loan advance in any sense. The purpose of the arrangement is to create something they can claim is a “replacement loan” which has been repaid (hopeless as that argument is technically), and then extract fees from the contractor dressed up as a repayment of the loan. This is another false document.

What kind of lawyer would draft such a document? We can look at the metadata:

It’s John Hardman again, the former solicitor, struck off for dishonesty, who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser.

Intentionally providing a false document to HMRC is very serious. HMRC commenced a criminal investigation against other loan scheme promoters for submitting false documentation to HMRC.

We have reviewed substantively identical “statements of no liability” and “loans” sent by six companies linked to Barrowman39We trace the links below, in “How responsible is Barrowman”? which acted as trustee lenders under contractor loan schemes:

- AML Management Limited: signed by Timothy Eve, the Deputy Chairman of Knox (Barrowman’s business).

- Smartpay Limited: also signed by Timothy Eve.

- Knox House Trustees Limited: signed by Anthony Page and Voirrey Coole. Page worked for Knox/Barrowman, and was a director of many Barrowman companies (including PPE Medpro) until he was sacked in disputed circumstances. Coole was a director of PPE Medpro and multiple other Barrowman-linked companies.

- Principal Contracts Limited: signed by Lisa Rowe.

- SP Management Limited, a Maltese company: signed by Timothy Blackburn (a senior member of Barrowman’s management team, and director of a number of Barrowman’s Maltese entities).

- SP Management Limited, an identically named Isle of Man company: signed by Lisa Rowe.

These individuals include some of the most senior people in Barrowman’s organisation.

These documents are sent on the headed notepaper of the separate companies. However, one client received documentation from Smartpay, Knox House and Principal Contracts on the same day, and the metadata suggests all three companies created documents using the same computer:40i.e. a Mac using the same os/version of Preview. This looks like a one-off: the other documents we have were either exported from Word or are scans.

How responsible is Douglas Barrowman?

As is typical of Barrowman, he is not a director or shareholder of any of the companies involved, and the Companies House entries don’t list him as the “person with significant control” (PSC).

The links between Barrowman and AML

The schemes were originally sold by AML Tax (UK) Limited, a UK company. Its director at the time in question was Arthur Lancaster – a senior employee of Barrowman.41Lancaster’s efforts to stymie an HMRC enquiry into the company were recently described by a tax tribunal as “seriously misleading”, “evasive” and “lacking in candor”. There is more about Lancaster here.

The other directors of AML Tax were Timothy Eve and Paul Ruocco. Eve is Deputy Chairman of Knox, Barrowman’s business. Ruocco is closely connected to Barrowman.

UK companies have to register their PSC at Companies House. AML’s registered PSC is Braaid Limited42The Panama Papers list Braaid as the road where Barrowman’s house is located., a BVI company.43On 9 September 2016 the PSC was listed as “Knox Limited Ref Willowbarn Trust”; this was then changed to Braaid Limited on the same day. A mistake? Or an accidental reveal of the real ownership structure? The rules don’t permit a BVI company to be a PSC – the entry should show the actual individual who has significant control or influence over AML – AML’s directors therefore broke the law.44Companies have to identify their actual human owners – they’re only permitted to identify companies as their PSCs/beneficial owners if those companies report their owners (preventing multiple duplicated filings). There are certain other cases where a PSC/beneficial owner can be a company which are not relevant here – there is helpful guidance in paragraph 2.2 here. So, for example, if I own UK company A which owns UK company B, then company B will declare that company A is the PSC, and company A will declare that I am the PSC. But if I own BVI company A which owns UK company B, then company B will declare that I am the PSC.

Despite this attempt at obfuscation, Barrowman has, to our knowledge, never denied his ownership of AML Tax – his defence is that “the schemes were lawful“. We don’t agree with that – after 2010 we believe they did not work and were not compliant with tax law. The way in which they were marketed and sold to unsophisticated individuals was disgraceful, and possibly fraudulent. Two courts have found that AML’s failure to disclose to HMRC under the “disclosure of tax avoidance schemes” (DOTAS) rules was unlawful. Another court found that AML’s failure to comply with HMRC’s information notices was unlawful. The failure to disclose Barrowman’s ownership of AML was also unlawful. This is a pattern of law-breaking.

The links between Barrowman and other scheme companies

Barrowman also controls other companies that sold schemes for AML, or sold essentially identical schemes to AML.

Dentists were sold schemes by AML Healthcare Contracts Ltd, later renamed to Denmedical (UK) Ltd. Barrowman himself was originally listed as the “person with significant control” of Denmedical; this was then changed to Anthony Page. Page worked for Knox/Barrowman until he was sacked in disputed circumstances.

Many contractors were introduced to the scheme by “Principal Contractors” – registered in the Isle of Man as a “business name” of Principal Contracts Limited, one of Barrowman’s companies.

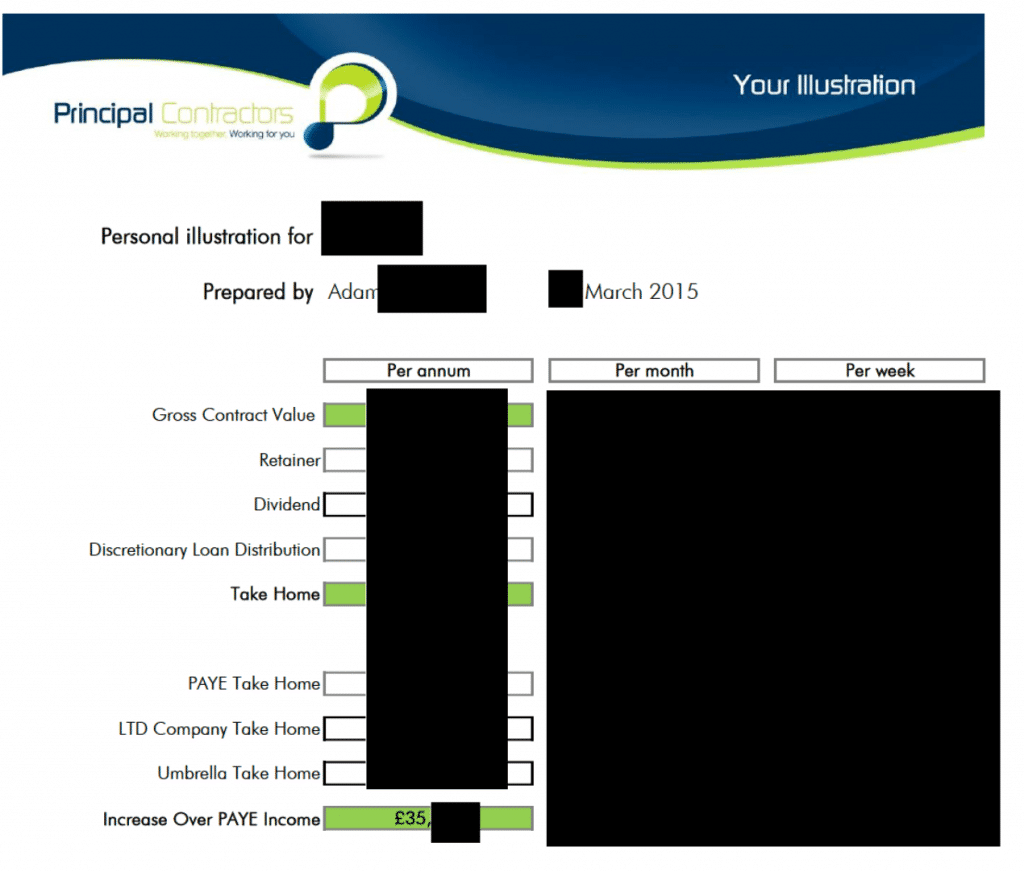

Here’s a financial projection prepared by “Principal Contractors” for a potential client:

And here’s the metadata for that document:45We assume this was Barrowman’s assistant, or someone using Barrowman’s computer; it seems most unlikely that Barrowman prepared the financial projection himself. We’ve redacted some of the metadata, and the details from the PDF itself, to protect our source.

Once clients signed up, the actual loans ended up being made by a variety of offshore company trustee entities, all connected to Barrowman. Many of the loans also show Hardman, or his firm (“HC Legal Consulting“) as the author.

Some of the early loans were made by AML Management Limited. Later loans were less easily traceable to Barrowman.

One example was SP Management Limited, a Maltese company owned by Soldado (PTC) Limited (which we have previously seen holding a property in Belgravia acquired by Barrowman and his wife). The metadata in the SP Management Limited documents shows John Hardman as the author – the former solicitor, struck off for dishonesty, who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser. Another example is an Isle of Man company also called SP Management Limited, with Knox House Trust Limited as its agent. 46It’s very unusual for groups to set up multiple companies with the same name in different jurisdictions – ordinarily one wants to avoid even similar names given the potential for confusion. We cannot think of a legitimate reason to do this – but Barrowman’s group often does. We do not know why.

As noted above, letters supposedly written by Smartpay Limited, PCL and Knox House Trust have metadata suggesting they were all prepared on the same computer.

Smartpay Limited made the outrageous December 2018 loan. Its letters to clients use Knox House as its address, and are signed by its director, Timothy Eve. Eve is Deputy Chairman of Knox, Barrowman’s business.47Oddly there is also a UK company called Smartpay Limited; its PSC is said to be Paul Ruocco. Most groups don’t register identically named companies in different jurisdictions, but Barrowman seems to make a habit of it, with one particularly well-known example. It is unclear what legitimate purpose this could have.

So we can confidently link Barrowman to AML and the other related companies selling the same scheme (as well as firms supposedly providing tax/accounting advice). It’s plausible that a large proportion of his fortune came from AML’s tax avoidance schemes.

The links between Barrowman and Vanquish

Whilst Barrowman doesn’t deny that AML is his company, he does deny a link to Vanquish Options Limited, possibly because he realises how very questionable, and potentially criminal, its actions were.

- His lawyers told The Times in 2019 that he denied having “any involvement or interest in Vanquish Options“.

- Barrowman’s lawyers told File on Four that neither he nor Knox48Knox Group plc is Barrowman’s main holding company; it owns Knox Family Office, holds/manages Barrowman’s own assets. Knox at one point had a business of running family offices for third parties, but it is unclear if that exists today other than on paper have at any time owned or controlled Vanquish.

- At the time Vanquish was selling its schemes, its personnel told clients that there was no link to AML or Knox House (which was important, because by that point most of the clients were very unhappy with AML). Here’s one contractor asking “Jamie” of Vanquish directly if the two companies share a director, or if Vanquish is a subsidiary of AML. The answer is a clear “no”:49This is part of the same recorded phone call covered in the File on Four broadcast, although they didn’t include this question/answer

Our starting point is that there is no reason to believe any denial by Barrowman that he is linked to a particular company, because it is now a matter of public record that he and his wife have admitted lying about their ownership of another company controlled by Barrowman, PPE Medpro. A lawyer who relayed one of their lies has issued a public apology.

And multiple lines of evidence evidence suggests that in reality Vanquish was part of Barrowman’s Knox Group:

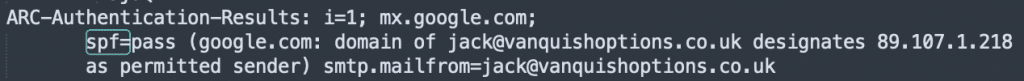

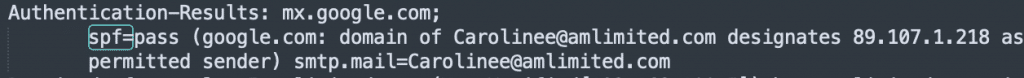

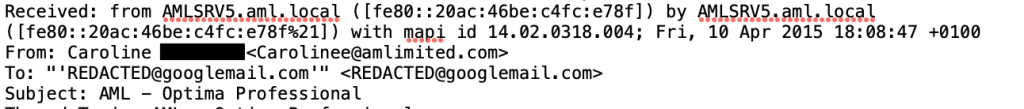

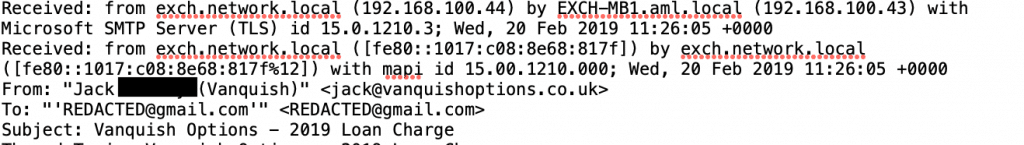

- Vanquish, AML and other Knox companies used the same email server. Electronically signed Vanquish documents show that Vanquish sent the document from IP 89.107.1.218, which geo-locates to Douglas, in the Isle of Man, where Knox is based. Vanquish’s email headers50All emails include “headers” which contain information about the sender, the recipient, and the route that the email took through the sender and recipient’s network, and through the public internet. This data is usually hidden, but it’s easy to reveal and analyse it – there is a good explanation and analysis tool here. show that its emails originate from the same IP address. Jamie denied being associated with AML, but his own emails come from the same server.51i.e. 89.107.1.218 was specified in the Sender Policy Framework (SPF) for the Vanquish domain. SPF is a protocol designed to prevent email impersonation. The receiving server checks that emails claiming to come from a domain originate from the SPF IP address. So 89.107.1.218 isn’t just a random node on the internet; it’s the email server from which the Vanquish email was sent, and which Vanquish officially designated as their email server. And AML emails also originated from that IP:52As do emails from Carnegie Knox, Grosvenor Tax (not to be confused with the unrelated Grosvenor Tax Services) and Principal Contractors Ltd.

- Vanquish, AML and Knox companies all used computers on the same network. Email headers show that emails from Vanquish (including Jamie’s) were all sent by computers on the “aml.local” subnet. We see the same subnet in emails sent by AML and other Knox companies:

- Vanquish shared a director with AML and its other directors are closely linked to Barrowman. Arthur Lancaster is a director of AML Tax; he is also a director of Vanquish Options Limited. “Jamie” in the audio clip above was straight-out lying. Lancaster was also Vanquish Options’ listed PSC at the time (he was also the PSC for PPE Medpro, but appears to have been (unlawfully) “fronting” that company for Barrowman. 53There was, again, also a Maltese company with the same name.

- Vanquish’s documents were written by AML/Knox personnel. Metadata in the PDF documents Vanquish sent to clients reveal that the authors included John Hardman (the struck off solicitor who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser), HC Legal Consulting (Hardman’s firm), Sandra Robertson (at the time a director of Barrowman’s Knox Group) and Nerys Roberts/Rowlands (head of marketing for the Knox Group, covering all entities owned by the Knox Group).54The Roberts document contains no information identifying a particular contractor, and so we have made it available here, and you can view the metadata yourself. We have established Roberts’ role from two independent sources, but there is no confirmation of this in any public material. There is clear evidence Roberts ran the “AML 250” network which managed referrals by advisers to AML – see Chartered One – “the Quarterly Bulletin of the Liverpool Society of Chartered Accountants”, edition 10 from Autumn 2014 contains an interview with Roberts. That’s not available online, but there is a Google cache available here, which we have archived here. Roberts’ marketing role also included Barrowman’s PTS Tax/c business, which claimed to help AML clients with their HMRC enquiries. We can demonstrate that Roberts worked for PTS thanks to metadata in PTS documents. These documents on their face were prepared only by Vanquish.

- AML Tax specifically recommended Vanquish Options to its clients (so far as we are aware, all of its clients). Barrowman’s other tax scheme companies did too. If Barrowman really had no interest in Vanquish, why would they do this?

- Knox businesses were involved in the structure. A bona fide structure to repay the original loans would not have required any involvement from the original Knox lenders of the contractor loans. However, in this case, the lenders were deeply involved, supposedly making the new 5% “loans” (which were not really loans at all). The lenders were all Knox businesses – Smartpay, PCL and Knox House Trust.

- AML admitted the link on one occasion. We have reviewed an email exchange between AML’s Isle of Man entity and a client. The client asked if AML was associated with Vanquish Options. AML replied that AML (UK) Tax “appointed” Vanquish Options “to assist with the loan charge once AML ceased trading”.

- The link is made even clearer by Companies House filings. Vanquish was established in 2008 as “Aston Ventures Consultants Limited”. “Aston Ventures” was Barrowman’s first successful business endeavour, a private equity fund of sorts. The register of debentures (i.e. lenders), and later its registered office, was at the offices of John Hardman’s law firm at the time (before he was struck off). The company soon became dormant, before being revived in 2018 when its name was changed to Vanquish Options Limited. During the time Vanquish Options was most active, its registered office remained Hardman’s law firm – it only changed in March 2019.

- There is a Maltese connection which also traces back to Knox. As File on Four reported, some of the Vanquish documentation creates a contract with Option 365 Limited, a Maltese company owned by Knox Limited, Barrowman’s company. Clients were also told to make their payments to Option 365. Barrowman’s lawyers told File on Four that the Option 365 shares were held for third parties (who they wouldn’t disclose). We note again that there are good reasons to be sceptical about such denials.

On the basis of this evidence, we believe that Barrowman’s denial of involvement in Vanquish was another lie.

How much money did Barrowman make from the schemes?

There are a large number of uncertainties here, but we can make a reasonably reliable lower-bound estimate based on the following figures and assumptions:

- Most of the schemes ran for about nine years.

- This case suggests AML’s fee was 16-18% of gross income (and that is consistent with what we hear from former AML clients).

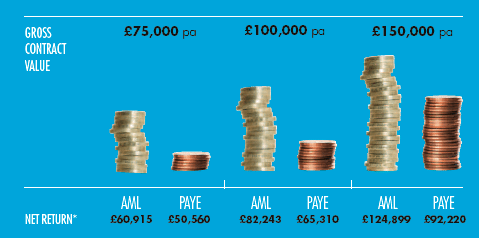

- Average contractor salary was around £75,000 (that’s consistent with HMRC’s figures and the data we’ve reviewed).

- About 67,000 contractors used loan schemes55This figure comes from the 21,900 loan charges HMRC has settled, plus the 45,000 that HMRC estimate have not settled – see these select committee minutes. The number will be higher than this, given that the loans were not disclosed on tax returns, and HMRC can only discover them if the taxpayer comes forward, the trustee/lender discloses the taxpayers’ identity (which they should, but may not), or HMRC’s own analysis of tax returns reveals that a taxpayer likely took a loan. However we have no idea how much higher the true number is. The Loan Charge Action Group believes the figure could be as high as 100,000.

- We’ll assume that at any given time only half of the 67,000 were using a scheme (on the basis that four or five years seems typical in the cases we’ve reviewed).

On this basis, the total fee revenue for all loan scheme promoters was approximately £3.6bn.56i.e. 9 x 16% x £75,000 x 50% x 67,000.

We can test this estimate independently by looking at HMRC’s stated recoveries from the loan charge. HMRC say they settled 21,900 cases of either individuals or employers, and the total tax brought into charge as a result of that was about £3.9 billion. That implies total loans of approximately £9.8bn57£3.9bn/40%, because the £3.9bn represents tax on the marginal rate, usually 40%, on the loan amount. Scale this up to the total 67,000 users and we have total loans of £29.8bn. 16% of that is £4.8bn. This will be an over-estimate because around 25% of the original £3.9bn is likely to include interest; the figure also includes companies. On the other hand, the marginal rate will be lower in many cases. But overall this confirms that our £3.6bn estimate is in the correct ballpark.

How much of the approximately total £3.6bn did AML and the other Barrowman companies receive?

AML was one of many promoters selling these schemes, but had a large presence in the market – informed sources have told us at least 10% and perhaps much more. In March 2022, the Loan Charge & Taxpayer APPG issued a call for evidence to loan charge users – the responses from scheme users disclosed 1,006 contractor loans, of which 295 (29%) were from Barrowman’s companies. That figure should, however, be used with caution, because these were voluntary responses to a questionnaire and not a random sample, and there could be reasons why the responses over-represent or under-represent Barrowman.

We will therefore prudently use the 10% figure, suggesting fee revenue for Barrowman’s companies of £360m, but plausibly the true figure was much higher (over £1bn if the 29% figure is correct).

(20 January 2024 update – we’ve seen an email from a Knox Group company dated 2015 which boasts they have 7,500 contractors on their books. If that was a true statement at the time that implies Barrowman’s companies had at least 12% of the market by 2019, and likely more)

This certainly won’t all have been profit for Barrowman – he had all the fixed costs that come from running a medium-sized business, and was also paying commission to independent financial advisers (IFAs) and accountants who referred clients to AML.

There are many uncertainties, but we believe it is safe to say that Barrowman made comfortably north of £100m from the original contractor loan schemes, and potentially much more.

We currently have no reliable way of estimating the income/profit from the Vanquish scheme. Only about one in twenty of the AML contractors who’ve contacted us used the Vanquish scheme, but that could easily be unrepresentative of contractors generally (in either direction).

Evidence for a prosecution

We believe this report demonstrates there is sufficient evidence for a criminal investigation and, if that supports it, a prosecution of some of the individuals responsible for the AML and Vanquish schemes.

There are several key questions: did AML and the other companies defraud their clients? Did they defraud HMRC? Which individuals and companies should be prosecuted?

1. Did AML and the other companies defraud their clients?

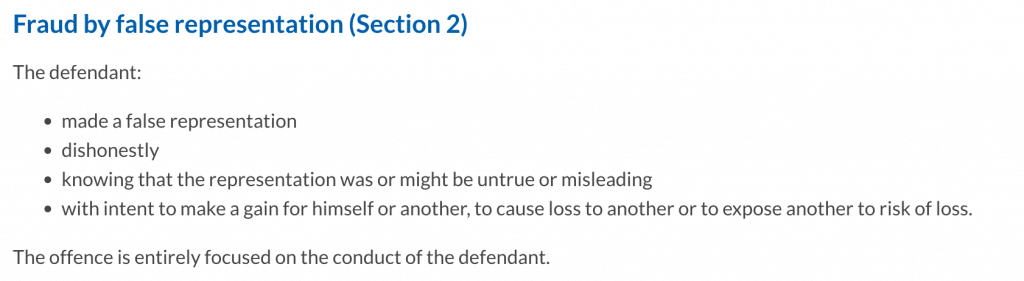

Here’s how the Crown Prosecution Service summarises the offence of fraud by false representation:

This report identifies numerous instances where individuals working for AML, Vanquish and other Barrowman entities made false representations to clients to gain or retain their business, in circumstances where we believe they must have known those representations were false:

- The implication that the original AML scheme had been “audited by a leading international accountancy firm”. We expect that was not true.

- The assurances that the original AML scheme loans wouldn’t have to be repaid. These were untrue.

- The assurances that the schemes were legally robust, when everyone in the sector knew that the Government had already threatened retrospective legislation to reverse remuneration tax avoidance, and had actually done so on one recent occasion.

- The claim in marketing brochures that the scheme had been “disclosed to HMRC”, when at the same time AML were assuring people in private emails that the scheme had not been disclosed under DOTAS.

- The claim that the schemes were “HMRC compliant”, which was understood by clients to mean that HMRC would not object to it – AML surely knew that HMRC would absolutely object to the scheme.

- The claim in emails to contractors that the trustees who’d be making their loan were “independent”, when in fact all the trustees we’re aware of were companies in Barrowman’s group.

- The claim that AML “employed its own in-house barrister”. We believe this was untrue.

- The fact at least one of the AML companies continued making loans even after the loan charge had been enacted, when the only consequence of those loans was (inevitably) a large tax liability for the contractors (plus, of course, fees for Barrowman’s companies).

- The claim that Vanquish was not linked to AML, including a specific claim by “Jamie” that AML and Vanquish had no directors in common. These claims were false; the companies had a key director in common; they used the same staff; they were on the same computer network and used the same email server.

- The description of the Vanquish scheme as a “preferred repayment opportunity” when it reality it was a very aggressive tax avoidance scheme.

- The claim, that the Vanquish scheme would work, when it had no technical prospect of working, and even a non tax-specialist would have realised that upon reading the whole of the legislation. That isn’t speculation – a (presumably) non-specialist on a web-forum took less than an hour to spot this point.58See the post here, responding to a question posed 55 minutes earlier. See also this post. A specialist – and Barrowman’s team hold themselves out as tax specialists – would also have appreciated that HMRC were easily able to counter it in any one of several different ways, with the potential for multiple tax charges plus penalties.59Vanquish claimed their scheme was “supported by tax counsel”. We’d be very surprised if the scheme they actually implemented was supported by tax counsel; if it was, that raises very serious questions for the tax counsel involved. And we would be amazed if an opinion didn’t include warnings about the TAAR, GAAR and further retrospective legislation. Saying “we have a KC opinion” is no defence – the question is, what does the opinion say, how was it obtained, and what precisely does it cover? There is more about KC opinions here.

- Furthermore, Vanquish were proposing a scheme to avoid the loan charge just days after HMRC had said schemes of that type wouldn’t work, and that HMRC would challenge them.

- Vanquish mentioned none of these issues to clients; their clear representation was that the scheme worked. This was enough to persuade some people, who couldn’t believe that an adviser would sell a scheme that didn’t work.

In addition:

- AML and then Vanquish stood to gain significant fees by selling the schemes, but would have no liability if the schemes failed.60You might say clients could sue AML/Vanquish for negligence. In principle that’s right; in practice these claims have very rarely succeeded, not least because promoter companies tend not to stick around to face the music. We are not aware of any successful claims against AML, Vanquish, or any of Barrowman’s companies.

- The scheme Vanquish actually implemented was not the scheme it told clients it would implement.

- Both the original contractor loans and the Vanquish loans were drafted by a former solicitor previously struck off for dishonesty.

- Vanquish did not stick around to defend its position; it stopped trading right at the point when its structure would become visible to HMRC.

Were the AML/Vanquish individuals involved “dishonest”?

That means asking whether their conduct was dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people (regardless of whether the individuals in question believed at the time they were being dishonest).61The subjective element of the test for dishonesty (see Ghosh (1982)) was removed by Ivey [2017] for civil cases, and that decision was confirmed to apply to criminal cases in Barton [2020]. The fact that a defendant might plead he or she was acting in line with what others in the sector were doing, and therefore did not believe it to be dishonest is no longer relevant if the jury finds they knew what they were doing and it was objectively dishonest. The leading textbook of criminal law and practice, Archbold, says:

“In most cases the jury will need no further direction than the short two-limb test in Barton “(a) what was the defendant’s actual state of knowledge or belief as to the facts and (b) was his conduct dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people?”

In our view it is plausible, even likely, that Barrowman’s team knew full well that what they were doing (particularly Vanquish) would not result in the advertised outcomes, would leave their customers exposed and yet create a profit for themselves. We expect most ordinary decent people would say that was dishonest; but ultimately that is something a jury would have to decide.

Given the terrible consequences of the schemes for AML’s clients, the clear public interest, we’d have hoped the CPS would have considered a prosecution. We don’t believe they did. We hope they reconsider in light of the evidence in this report.

There is no statute of limitation on criminal fraud.

2. Did Vanquish defraud HMRC?

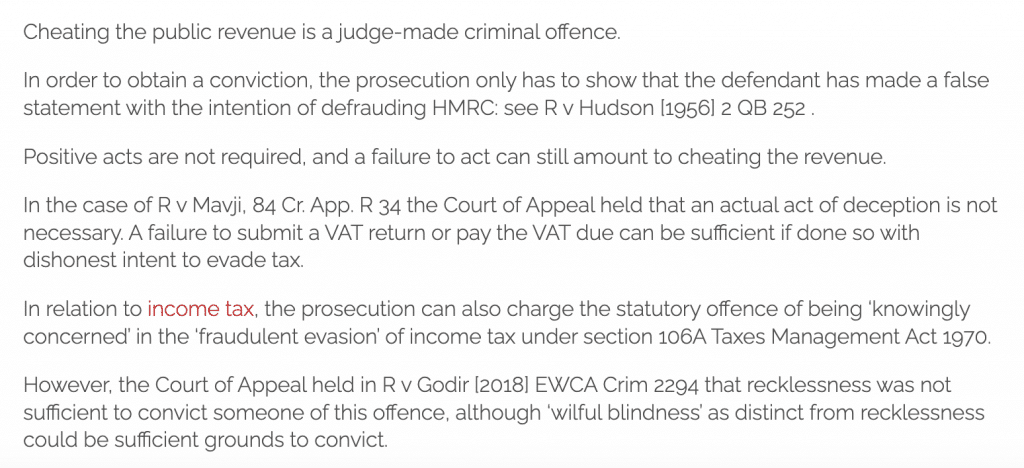

There’s a good summary of the law on “cheating the revenue” (the technical term for “tax evasion”) from barrister Patrick Cannon:

There are also statutory offences, for example s106A Taxes Management Act 1970:

![106AOffence of fraudulent evasion of income tax

(1)A person commits an offence if that person is knowingly concerned in the fraudulent evasion of income tax by that or any other person.

(2)A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable—

(a)on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding [F212 months] [F2the general limit in a magistrates’ court] or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum, or both, or

(b)on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years or a fine, or both.](/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Screenshot-2024-01-18-at-11.07.20-1024x202.png)

We can identify the following false statements made, or facilitated by Barrowman’s companies:

- The scheme involved producing false documents, procured by Vanquish and signed by the directors of AML Management Limited, Smartpay Limited, Knox House Trustees Limited, Principal Contracts Limited, SP Management Limited (Isle of Man) and SP Management Limited (Malta). There were loans that said on their face that money was being lent, when it was not. There were statements that loans had been repaid, when they had not been (in either the usual meaning of the word “repaid” or its technical tax meaning in this context). These documents were produced for the purpose of leading HMRC to believe (incorrectly) that the loan charge would not apply.

- Vanquish told clients to submit false tax returns, declaring no disguised remuneration loans, and including a note in the “white space” on the tax return reading “I did receive loans that were caught by the loan charge, but these were all repaid by 5 April 2019”. The loans were not repaid, so this statement would again be false.

- Whilst we have not been able to verify this, there is one report that Vanquish told a client that, after the Vanquish structure had been executed, the trustee would report a zero loan balance to HMRC (and not disclose that the Vanquish structure had been used). Any such report would be false.

- The stated technical basis for the Vanquish scheme, on the strength of which clients filed their tax returns, was false, and anyone reading the legislation (even a non-specialist) would have realised it was false.

- Vanquish told its clients not to mention the arrangement to HMRC: “We do not want to weaken the position of the individual by giving out any information that could end up with HMRC”. That is not how normal tax advisers behave. Advisers have been prosecuted for failing to disclose material facts to HMRC.

Were these false statements made with the intention of defrauding HMRC? That again comes down to whether the individuals in question were being dishonest, by the standards of an ordinary decent person. On the evidence available to us, we expect an ordinary decent person would regard the making of these statements as dishonest, but ultimately that is a question for a jury to decide.

In our view, the evidence is strong enough, and clear enough, that a prosecution is in the public interest.

There is no statute of limitation for tax fraud. However, Vanquish will soon be wound up, complicating any investigation – HMRC and other interested parties may wish to act to prevent this.

(It possible that AML and the other loan scheme companies were responsible for false statements during the period when they were active, prior to Vanquish (particularly during the post-2016 period when it was very obvious that the loan schemes were doomed). However, our detailed analysis of scheme documentation for this report was limited to Vanquish.)

3. Who should be prosecuted?

A criminal investigation would be able to identify all the people involved in the false statements and potential frauds identified above, but from our research we can identify the following individuals:

- False documents were signed by the six lenders who participated in the Vanquish arrangements. The signatories were the directors of those companies: Timothy Eve, Anthony Page, Voirrey Coole, Lisa Rowe and Timothy Blackburn. Eve and Rowe were, we understand, responsible for the day-to-day management of the tax business. The others may or may not have been familiar with every aspect of the Vanquish structure, but as directors we expect they knew that new loans were not really being made, and the old loans were not really being repaid. Yet they signed documents saying they were.

- Metadata indicates that false documents were drafted by John Hardman.62Noting our caution above about reaching conclusions from metadata

- Metadata indicates that Sandra Robertson and Nerys Roberts/Rowlands were involved in the marketing of the Vanquish scheme. We do not know how much they knew about the details.

- The directors of Vanquish were Arthur Lancaster (who we understand takes a key role in the design of the Knox Group’s tax products), Timothy Eve and Paul Ruocco. We do not know what role Ruocco had in the business.

- Douglas Barrowman ultimately controls all of the entities named above. We do not know how involved he was personally in the actions of the entities and their personnel, but given the very large amount of money these businesses made for him, and the involvement of some of his most senior personnel, it is in our view unlikely that he was a mere passive investor.

- False representations were made by more junior Vanquish personnel; it is possible that their understanding of the arrangements was such that they did not realise what they were saying was false, and they were just following a script, but the denial by “Jamie” of a connection between Vanquish and AML appears to have been intentional deceit (and it doesn’t seem from the recording as if “Jamie” was following a script).

In addition, Barrowman’s companies may themselves be liable for the corporate criminal offence of facilitating tax evasion.

The potential for civil claims

Our findings raise the possibility that a civil claim could be made against various entities in Barrowman’s group, for example based on deceit, unlawful means conspiracy or negligent misstatement. There is also the potential to bring deceit/conspiracy claims against Barrowman himself, and the directors of his companies, on the basis that they were the real controlling minds behind the statements, or were party to a plan that others made.

Any such claim would not be straightforward, particularly given the passage of time and the difficulty of establishing what precisely was relied upon – nevertheless the evidence we’ve assembled, particularly in relation to Vanquish, suggests this is worth serious consideration.

As a practical matter, the initial challenge would be organising a group claim, and arranging funding and/or insurance – given the amounts that contractors have lost as a result of Barrowman’s schemes, they will rightly be reluctant to put their own money at risk. We hope that there are law firms willing and able to take this forward.

Why prosecute?

In our view, Barrowman is morally responsible for the damage caused by the AML and Vanquish schemes to thousands of people, including two suicides. Whether he’s legally responsible, and whether he knew about, was complicit in, or directed, the numerous false statements made by his associates, is something that should be considered by a jury.

If, on the other hand, the behaviour of Barrowman and his companies – the false representations, the impossible legal positions, the false documents, the obfuscation and lies – does not result in prosecutions, then Barrowman and other bad actors will know they can act with impunity, and make illicit fortunes without any accountability.

Barrowman’s response

We gave Douglas Barrowman the opportunity to respond to the serious, specific and evidenced allegations we make in this report. His lawyers, Grosvenor Law, initially responded with an entirely non-specific denial – “your outright and unqualified allegations of dishonesty, wrongdoing and misconduct are denied by our clients in their entirety.”

The only point of substance in their response was a claim that the AML and Vanquish arrangements were properly notified to HMRC. We believe that is untrue – it’s reasonably clear from the evidence we cite above that neither the original AML nor the Vanquish structures were properly notified to HMRC. So we’ve asked Grosvenor Law why they are relaying this false claim. They have so far refused to answer.

His lawyers also claimed to be acting for Barrowman and the “Knox Group”. Given Barrowman’s previous attempts to conceal the identity of his the members of his group, we asked specifically which companies Grosvenor Law were acting for. They have, again, refused to answer. It highly unusual, and may be improper, for a law firm to refuse to identify its clients.

The full email chain is available as a PDF here.

The BBC asked Grosvenor Law specifically if Barrowman now accepted that his previous denial of links to Vanquish was misleading. The lawyers responded with another generic denial:

STATEMENT BY THE KNOX GROUP

The Knox Group denies any and all allegations of dishonesty, misconduct and wrongdoing. HMRC has had disclosures of all relevant documents and information relating to the loan charge arrangements for a lengthy period and the parties have been engaged in an ongoing and extensive process of dialogue and disclosure with the HMRC for several years in relation to such schemes.

HMRC has had all relevant materials for several years during which time it has never even suggested, let alone alleged, that there has been any form of dishonesty or wrongdoing by the Knox Group.

For the BBC to allege otherwise is speculative and not justified.

The Knox Group deeply and sincerely regrets that any contractor or their families suffered any distress or anguish arising from tax charges levied by HMRC when it retrospectively and retroactively amended the relevant legal framework. This retrospective change in the law was a matter of industry-wide criticism at the time from bodies such as the Chartered Institute of Taxation and the Institute of Chartered Accountants.

This is a weak response, which fails to engage with the substance of our evidence and our accusations, and which notably fails to even defend Barrowman’s past denials of his link to Vanquish.

The claim that HMRC has not alleged wrongdoing is false. We do not know if HMRC has ever suggested dishonesty, but we also do not know if it has had access to the same information as us.

This is also a misrepresentation of the CIOT, which has said the loan schemes were contrived avoidance schemes which were always likely to be robustly challenged by HMRC. Advisers expected challenges, and the Government had expressly warned of retrospective legislation – the question is why Barrowman’s businesses hid this from their clients.

Grosvenor have since added:

By way of context, HMRC estimate that there are 50,000 tax payers in the UK who have used a loan scheme. My instructions are that a large number of companies and professional advisors promoted these (legally compliant) schemes at the time: the Knox Group accounted for a small percentage of this number overall.

The fact other promoters were pushing similar schemes is irrelevant; we are specifically identifying evidence of fraud by the Knox Group.

Many thanks to M, the remuneration tax guru who provided most of the technical content for this article on the schemes and the loan charge, and wrote the first draft. Thanks also to K and N for tax law input, to L and Michael Gomulka of 25 Bedford Row for the criminal mens rea and dishonesty content, to H for the “cheating the revenue” analysis, and to Y for general insight. Thanks to F and B for their invaluable review and research, and P for advice on metadata and email IP address tracing. Thanks to the advisers working with former Vanquish and AML clients who provided their expertise and experience (particularly T). Thanks to Ray McCann (former senior HMRC inspector and past President of the Chartered Institute of Taxation) for reviewing a late draft, and to YK for a critical review and her invaluable suggestions on how to best structure this report. Thanks to PS for a final read-through. And thanks, as ever, to J.

Thanks to The Times and File on Four for their journalism that originally exposed the Vanquish scheme.

Thanks to Simon Goodley at the Guardian, and Ben Chu and team at Newsnight.

Most of all, thanks to all of the the clients/victims of AML and Vanquish who spent time corresponding with us, and digging out old documents and emails – we can’t name them, but the evidence highlighted in this report would never have been found without them.

-

1We nevertheless cover only a very small part of the history – a big omission is IR35. Anyone interested in the full background should start with the Morse Review

-

2We’ll ignore the personal allowance to make the calculation easier

-

3One of the key originators of the scheme was Paul Baxendale-Walker – a barrister and solicitor who moonlit as a porn star, and eventually ended up struck off, bankrupt, and convicted of fraud. It’s very strange that someone so peculiar was responsible for so much damage to the tax system, to many peoples’ lives, and led to the downfall of a football team. There’s a good summary of much of this in the Wikipedia article on Baxendale-Walker, but be warned that the article is out of date and parts of it appear to have been written by him.

-

4Interestingly, in 2022 John Caudwell said he was “extremely proud” of paying tax in the UK and “absolutely wouldn’t” use loopholes to save money again.

-

5See paragraph 18 of the case here

-

6The old Special Commissioners, who heard first instance tax appeals until the modern tax tribunal system was adopted in 2009

-

7HMRC did appeal on the question of whether the company was entitled to a deduction for its payment to the EBT, but didn’t appeal on the question of whether the individuals should be taxed on the loan amounts.

- 8

-

9i.e. mundane vanilla transactions, not tax-motivated transaction, as by that time major law firms would rarely if ever advise on tax avoidance arrangements

-

10As late as 2014, the First Tier Tax Tribunal (FTT) and (on appeal) Upper Tier Tribunal (UTT) found for the taxpayer in Murray Group Holdings (the Rangers case) on the basis that the repayment of the loans was not a “remote contingency”. This showed a remarkable failure by the tribunals to understand what was going on – these structures only make commercial sense if the loans aren’t repaid. The “loans” are, in reality, not loans at all.

-

11Although other AML entities appear to have started to run schemes as early as 2006

-

12Barrowman had numerous companies selling what was always basically the same scheme. This video is badged “Principal Contractors”. A lawyer looking at their emails and website immediately sees something odd: no company name is ever stated, just “Principal Contractors”. We can find no evidence that company ever existed. However “Principal Contractors” is registered in the Isle of Man as a “business name” of Principal Contracts Limited, one of Barrowman’s companies. We can also tie Barrowman directly to documents sent out by Principal Contractors.

-

13The point being to identify avoidance structures early to “inform legislation to close loopholes” (see e.g. paragraph 2.2. here

-

14AML has twice been found by a court to have unlawfully failed to disclose under DOTAS; those schemes were slightly different, but we believe all were disclosable. We’ve reviewed a email explaining AML’s basis for not disclosing under DOTAS in 2015, and in our view it’s clear AML was acting unlawfully.

-

15In theory the structure could have been disclosed on some informal basis, but that would be contrary to HMRC’s usual practice. Another possibility is that elements of the scheme were individually disclosed in response to preliminary HMRC enquiries. But we would very much doubt the whole scheme was confirmed, outside DOTAS.

-