In 2016 and 2017, libel firm Carter-Ruck acted for a business called OneCoin, and threatened defamation proceedings against people who alleged OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme and a fraud. In fact OneCoin was a giant Ponzi fraud – second only to Madoff. Plenty of people realised this at the time. Why did Carter-Ruck agree to act for them?

We’ve investigated the history in detail. It presents a picture of a firm recklessly acting for a client it should have known was a fraud, and recklessly making accusations it should have known were false. It’s likely that Carter-Ruck’s actions caused more people to lose more money to the fraud – and this was foreseeable at the time.

OneCoin

OneCoin was founded in 2014. It presented itself as a cryptocurrency, akin to BitCoin, which was “mined” by computers, held on a blockchain, and traded on an exchange. OneChain was aggressively marketed online and offline.

Everything was a lie – OneCoin was one of the biggest scams in history. There was no “mining”. There was no blockchain. The “exchange” presented fake prices, designed to make investors think the price of OneCoin was rising when, in reality, there was no price at all. OneCoin was a fraud from the start – a Ponzi scheme, where new investors’ money was used to pay old investors. It also had pyramid scheme features – existing investors were incentivised to sell packages to new investors, who’d pay up to €118,000 for worthless “training courses” accompanied by “tokens” that could be exchanged for OneCoins1The “training courses” being an attempt to evade prohibitions on pyramid schemes that don’t actually sell products, and securities regulations that in many countries would prohibit direct sales of OneCoin

OneCoin failed spectacularly in 2017, and its executives are all now either in jail or in hiding. Around $4bn was stolen from millions of investors, across 125 countries. Its founder, Ruja Ignatova, is one of the FBI’s ten most wanted fugitives.2A side note: Ms Ignatova claimed to have studied European law at Oxford University. A poor quality scan of a degree certificate is available, which purports to show her having studied at St Hilda’s, and received a Magister Juris. There’s an open question if her Oxford qualification is genuine; media reports generally report her degree uncritically, but sources from St Hilda’s are sceptical she was there. I’ve asked St Hilda’s if they can confirm, and I’ll update this if I hear back.

Carter-Ruck and its decision to act for OneCoin

Carter-Ruck is possibly the UK’s most well-known libel-specialist law firm. At some point in 2016 it decided to act for OneCoin and Ruja Ignatova. How did it make that decision?

I was a partner in a large law firm for many years. Before a partner could act for a new client, a team went through procedures to check the bona fides of that client and their business. This included searches of the internet and other open source materials, as well as searches of private databases. Partly this was about protecting the firm’s reputation. But also it was about the serious consequences for a law firm which facilitated criminal activity or received money that was the proceeds of crime. I am not giving away any secrets by saying this, because these are procedures followed by all UK law firms.3The nature of many law firms’ work means they are also covered by anti-money laundering rules, which require more onerous procedures. I expect Carter-Ruck are not in scope of the AML regulations, and therefore this article assumes they were only required to undertake more basic due diligence.

What would reasonable due diligence have found in mid-2016, if we limit ourselves to material available on the public internet?

First, OneCoin’s own publicly available promotional material should have alerted any reasonable person to the likelihood that this was a fraud:

- A widely circulated projection prepared by OneCoin in 2016 claimed to show that in its “base case”, the value of each OneCoin would increase 200 times in two years. That should raise an immediate red flag.

- In 2015, OneCoin claimed it had been audited by a firm called Semper Fortis.4OneCoin published a somewhat odd video of Ms Ignatova interviewing the senior partner of Semper Fortis. It comes as no surprise that the audit turned out to be have been written by OneCoin staff. At that point OneCoin had a market capitalisation of around $2bn. Semper Fortis was a small and unknown firm with no obvious credentials. As at January 2016, its website consisted of one page saying “under construction”. The comparison with Madoff’s obscure auditor is obvious (although there aren’t many other similarities; the warning signs Madoff was running a Ponzi were much more subtle than those for OneCoin, and Madoff likely started off running a real investment fund).

- At a lavish event at Wembley Arena in June 2016, Ms Ignatova had said that OneCoin would double the number of coins in circulation, but the price of each coin would not change. That is not plausible.

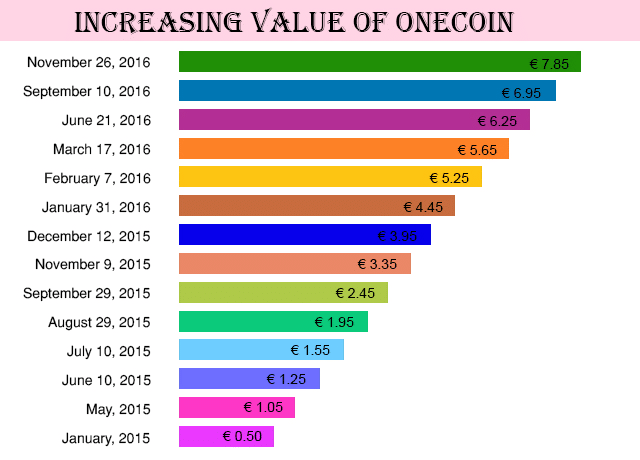

Second, one glance at OneCoin’s price showed that it did not behave like any cryptocurrency, or indeed any asset with a market price:

No real asset goes up over time so inexorably (noting of course that the bar chart has no scale and so the steps are not actually as regular as the chart suggests).

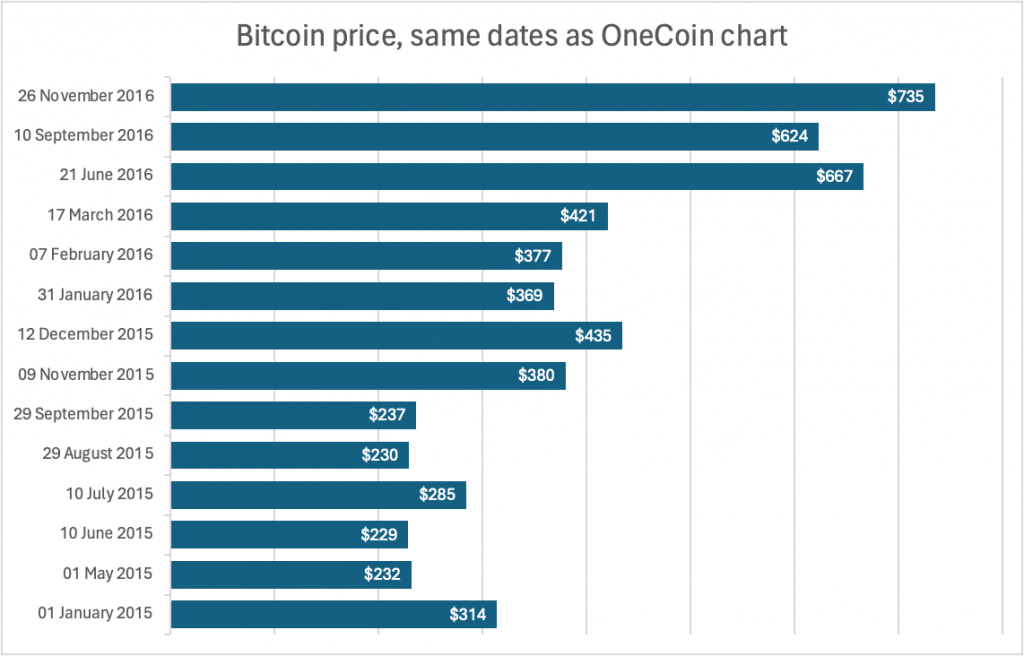

For comparison, here is the Bitcoin price on each of those dates:5Source: data from Yahoo Finance, chart by Tax Policy Associates Ltd. You can see a more conventional chart of the Bitcoin price here; no amount of cherry-picking dates will create a result like the OneCoin chart.

Third, The reported history of Ms Ignatova and OneCoin revealed additional signs of fraud:

- Ms Ignatova and her father had been accused of fraud in 2012 in connection with an acquisition of a foundry in Waltenhofen, Germany, which they asset-stripped and then bankrupted.6There is much more about this in Jamie Bartlett‘s book, however the Kreisbote article is probably all that would have been easily found by a desktop search exercise in 2017. That should have been enough to raise a red flag.

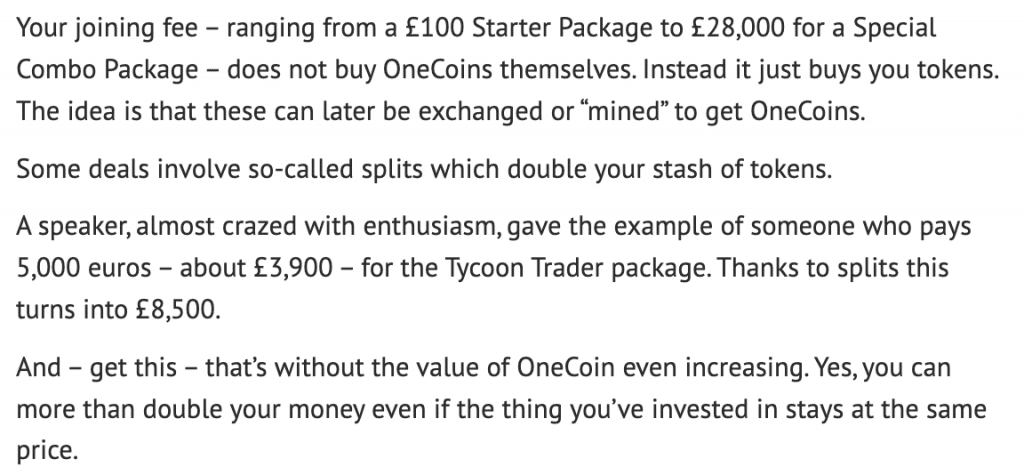

- In February 2016, the Daily Mirror had reported on a cult-like recruitment rally where OneCoin representatives presented a pyramid scheme-style fee structure, with some unbelievable claims about the price:

- In March 2016, the Swedish and Norwegian police had started investigating OneCoin. The Norwegian Direct Selling Association warned that OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme and a fraud.

- That same month, the Finnish Broadcasting Company reported (in English) that local police had interviewed OneCoin staff, and – more seriously – that the business was turning over €3bn, with cash paid by OneCoin “investors” going through a chain of companies that ended up with Ms Ignatova’s mother.

- There were numerous articles and postings online by cryptocurrency experts (like this, this, this, this, this and this) making a compelling case that OneCoin was not a cryptocurrency, but rather was a Ponzi fraud. In fact I’ve been unable to find a single article at the time by anyone with cryptocurrency expertise expressing a different opinion. This itself was evidence of fraud: cryptocurrency was a small world, and everyone knew which developers were developing which blockchain. Nobody knew anyone who’d developed a blockchain for OneCoin.

Should Carter-Ruck have agreed to act for OneCoin in mid-2016 given all these warning signs?

Coin Telegraph

Coin Telegraph is a website publishing news on the cryptocurrency industry. An indication of its prominence is that its Twitter account has 1.9 million followers.

In May 2015 it published an article: “One Coin, Much Scam: OneCoin Exposed as Global MLM Ponzi Scheme“.

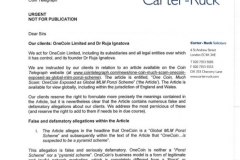

On 8 July 2016, Coin Telegraph received a letter from Carter-Ruck (PDF version here):

There are some very questionable elements to this letter.

1. False labelling

The letter is labelled “private and confidential” and “not for publication”. Nothing in the letter constituted confidential information. The claim it was “confidential” was false. In my view, these false claims are included to mislead non-legally qualified recipients, in an attempt to prevent libel threats from being published.

The Solicitors Regulation Authority said last year that this kind of false “labelling” of letters is unacceptable. This was not a change in practice: solicitors have never been permitted to mislead third parties.

2. Claims without merit

The letter threatened legal action if Coin Telegraph did not comply within seven days; it was a pre-action letter. It should, therefore, have complied with the pre-action protocol for defamation. This requires that a claimant should explain why a defamatory statement is incorrect. But, whilst the letter asserts that the allegation OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme was “false and seriously defamatory”, indeed so egregious as to amount to a malicious falsehood, at no point does the letter explain why the statement is incorrect.

It makes an attempt to do so which betrays a complete lack of understanding by Carter-Ruck:

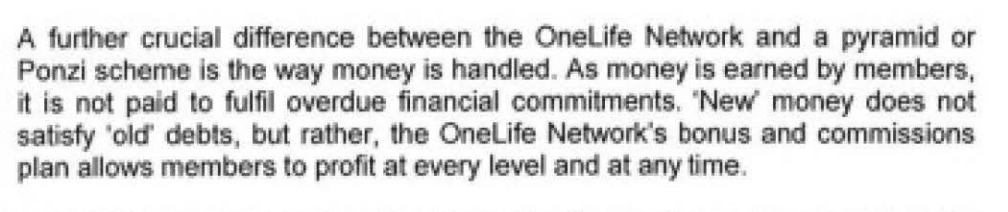

If new investors’ money is being used to pay out bonuses and commissions to existing investors then that absolutely is a Ponzi scheme. Carter-Ruck just admitted the very thing they were trying to deny.

The charitable interpretation is that Carter-Ruck had no idea what pyramids or Ponzis were, and didn’t understand the accusation being made. “Money earned being paid to fulfil overdue financial commitments” is not a correct definition of either a Ponzi scheme or a pyramid scheme.

The denial that OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme was, therefore, completely without merit, and refuted by the facts set out in Carter-Ruck’s own letter. They had, it seems, failed to speak to anyone with knowledge of financial fraud. This was reckless, incompetent, or both.

3. False claim about Greenwood and Allan

Second, Carter-Ruck’s letter makes a factual claim which five minutes’ research would have revealed was false and misleading.

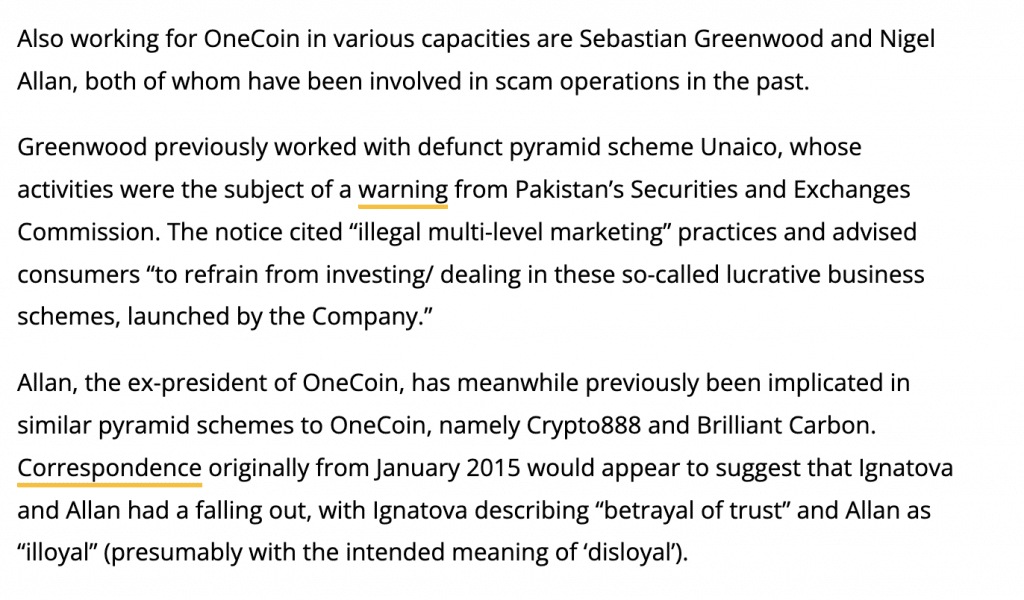

The Coin Telegraph article says this:

Carter-Ruck doesn’t deny the dubious history of the two individuals, but denies (or, at least, appears to deny) any connection between them and OneCoin:

This is a very peculiar paragraph. Coin Telegraph didn’t say they were “directors”. It said they were “working in various capacities” and that Allan was the “ex-president” of OneCoin. A Google search in 2016 would have immediately revealed that these statements were true:

- This slide deck from April 20157which we’ve made available in more readable form as a PDF here shows Greenwood as one of the two founders of OneCoin. This April 2016 interview and the Wembley Arena show gives him prominence second only to Ruja Ignatova. Greenwood’s “about me” website said that he had established the OneWorld Foundation (a supposedly charitable offshoot from OneCoin).

- Nigel Allen had been the first President of OneCoin. Here is his Facebook page from 2014. Here is an official early OneCoin YouTube video from February 2014.

This was, therefore, a false and misleading statement by Carter-Ruck, and one which even cursory investigation would have shown to be misleading. The claim that Coin Telegraph’s accusation was false and defamatory was completely without merit.

Either Carter-Ruck knew the statement was false, and made it anyway, or (more likely) was given the statement by their client and made no attempt whatsoever to check it.8I suppose a possible defence is that “we just said they weren’t directors and that is correct – they weren’t directors”. But if that was indeed the rationale, then this was a deliberate attempt to mislead.

Either way, the statement should not have been made.

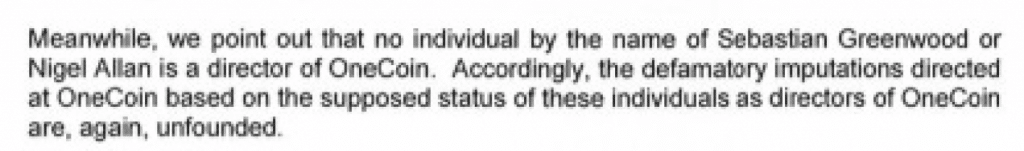

4. Abuse of data privacy law

The letter seeks to use the Data Protection Act as a weapon to silence Coin Telegraph:

Introducing a data privacy angle into what is really a defamation claim is a classic SLAPP tactic, designed to overload the defendant and obtain information on their sources. A similar tactic, also involving Carter-Ruck, was recently criticised by the High Court in the Amersi v Leslie case.

Carter Ruck’s use of it here is particularly egregious, because it fails to recognise the journalism exemption.9As this was 2016, the pre-GDPR position applied It is not appropriate for a law firm to advance an argument to an unrepresented person when it knows that a defence is potentially available.

Jen McAdam

Jen McAdam lived in Scotland and had worked as an IT B2B sales consultant. She’d invested her life savings in OneCoin, and encouraged her family to invest. By 2017 she had become convinced that OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme, in part based upon accusations made by Bjørn Bjercke, a Norwegian cryptocurrency expert.

Ms McAdam discussed the accusations with Mr Bjercke in this webinar in April 2017:

Mr Bjercke made two key allegations:

First, that he and others had undertaken extensive testing, and found that when OneCoins were sold from one account to another, the transactions were not visible on OneCoin’s supposed blockchain. Mr Bjercke went into some detail as to what he had found. Given that the whole point of a blockchain is to be a robust and unalterable record fo transactions, the obvious conclusion was that the blockchain was being faked.

Second, that he (and other blockchain specialists he knew) had been approached by recruiters for OneCoin at the end of September 2016 to build a new blockchain for OneCoin. That contradicted OneCoin’s claim that it had switched over to a new blockchain on 1 October 2016.

Mr Bjercke and Ms McAdam featured again in this Youtube video, and then another webinar10I haven’t been able to locate it; the link given by Carter-Ruck was https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OmQtWRd_FqU, but that link is now dead. The videos were posted by an account called “Crypto Xpose”, but Ms McAdam linked to the videos on her Facebook page.

This is what happened next:

Why was Carter-Ruck still acting for OneCoin in April 2017?

By this point there were considerably more signs that OneCoin was a fraud:

- Ms Ignatova had appeared on a promotional video in July 2016 claiming that anyone buying a €118,000 training course would receive 1,311,111 tokens, worth around $5m, which would turn into even more (around $14m) after OneCoin launched their “new blockchain”. These are, again, not credible claims.

- As Ms Ignatova had promised at the London event (reported by The Mirror), the supply of OneCoins doubled on 1 October 2016, but the price per-coin didn’t change. This should not be possible.

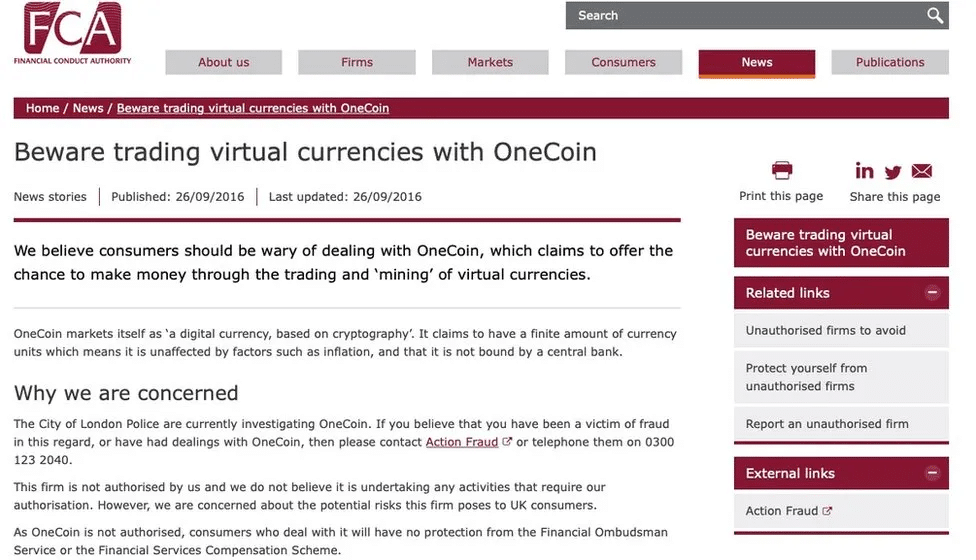

- On 26 September 2016, the FCA published a warning that consumers should be wary about OneCoin, and that the City of London Police was investigating it:

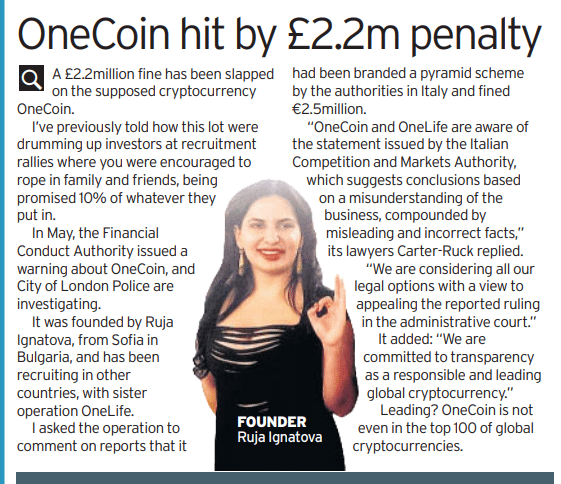

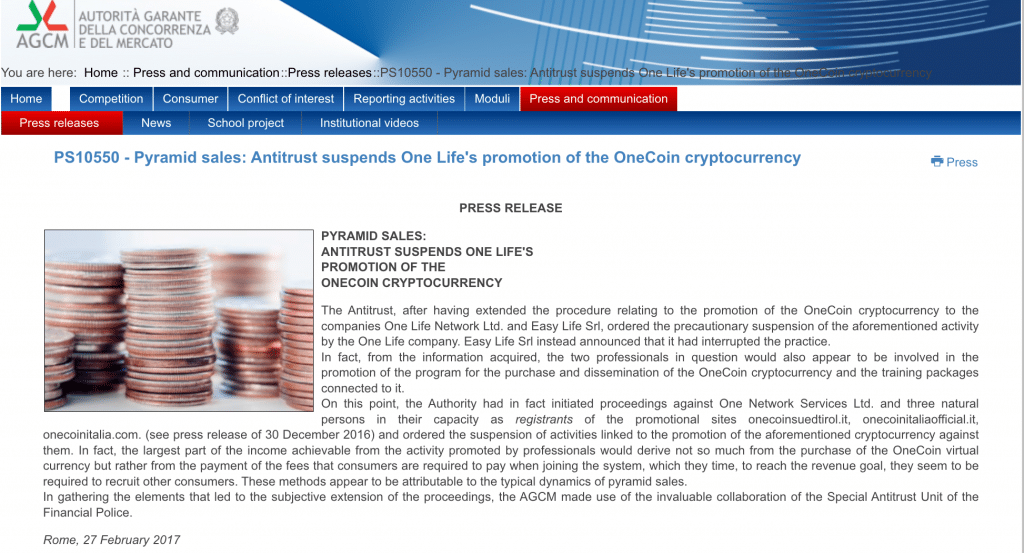

- In December 2016, the Italian Anti-Trust Authority suspended all promotion of OneCoin on the basis that it was a Ponzi/pyramid scheme, the Hungarian Central Bank warned that OneCoin was similar to a pyramid scheme, and the Austrian Financial Markets Authority issued a specific warning about OneCoin.

- Also in December, a Bulgarian newspaper reported that Ms Ignatova had transferred her legal ownership of the business to a 25 year old with a past history of selling his identity. This followed a previous article about Ms Ignatova’s pattern of suspicious transactions.

- In January 2017, OneCoin suspended clients’ withdrawals of money, but continued to accept new funds.

- In March 2017, the Croatian Central Bank issued a warning about OneCoin, referring to the warnings issued by other European authorities and regulators.

- Semper Fortis, the firm which had “audited” OneCoin in 2015 didn’t publish an audit for 2016 or 2017. As at April 2017 its website still consisted of one page saying “under construction”.

- Bob Summerwill, one of the founders of Ethereum, had described OneCoin as a “scam”, and explained why.

- The OneCoin Wikipedia page by this point stated OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme, and linked to multiple sources questioning OneCoin’s bona fides.

- British Muslims were a particular target for OneCoin sales (together with other minority groups). In November 2016, a paper was published by Wifaqul Ulama, a body representing Islamic scholars in Britain – it concluded that OneCoin involves fraud and deception, and therefore it was impermissible for Muslims to invest in the product. The value of the paper for non-Muslims is its careful and detailed analysis of the history and workings of OneCoin, and its extensive footnotes and links. The paper presents the clearest and most complete picture I can find of OneCoin as at late 2016 (although many of the links are now dead).

I found the materials listed above, and those in the pre-2016 section, after about two hours of basic internet research, using only Google, looking only at pre-April 2017 materials, and using only simple search terms11“onecoin ponzi”, “onecoin fraud” and so on. I didn’t use any terms which relied upon post-2017 knowledge, e.g. the names of the entities later discovered to be laundering the funds. I expect an experienced KYC professional would have done a better job, faster. A KYC professional would also have had access to newspaper archives, credit reports, corporate ownership databases and other private resources.

But we don’t need to speculate on what Carter-Ruck’s due diligence could have uncovered in 2017, because we can see the actual actions of two other firms.

First, thanks to a US civil judgment – we can see the findings of Bank of New York’s compliance team in December 2016. BNY had processed large transfers for a OneCoin affiliate, and so their compliance team was tasked with researching OneCoin. Using only standard internet searches, they concluded that OneCoin was operating a pyramid/Ponzi scheme (see page 7 of the judgment).

Second, thanks to testimony in a US criminal trial, we can see how Apex Fund Services, a UK investment fund administrator, reacted when they saw OneCoin’s name. Apex was administering a fund for a lawyer, Mark Scott. Paul Spendiff, a managing director at Apex, was concerned about the identity of Scott’s proposed investors. He spent the weekend of 30 June 2016 looking through the Apex team’s historic emails – and found one where Scott had accidentally included a previous email instructing him how to proceed, sent to him from an address at onecoin.eu. Paul Spendiff started Googling OneCoin and, when he saw the Mirror story and various online investigations into OneCoin, he reacted by calling an emergency meeting with his risk and compliance teams, and filing a “suspicious activity report” with his anti-money laundering regulator.12This is all from Spendiff’s testimony at Scott’s trial for money-laundering. I can’t find a primary source, but there is a good summary in this Twitter thread (unrolled here) and in Jamie Bartlett‘s book The Missing Cryptoqueen

Note that Spendiff and BNY made their conclusions in 2016. It was on 1 January 2017 that OneCoin blocked its “investors” from withdrawing their money – a significant additional warning sign.

Why did Carter-Ruck reach a different conclusion to Spendiff and BNY’s compliance team?

Carter-Ruck’s decision to act as a PR firm

We know that Carter-Ruck was aware of at least some of what was going on, because they issued a statement responding to the decision of the Italian Competition Authority. This is from The Mirror, 17 February 2017:

And this is what the Italian Competition Authority had said (rough Google translation):

A law firm is not a PR agency, and needs to be careful when it acts like one. There’s nothing that stops a PR agency from simply repeating the claims of its client, regardless of their apparent truth. Indeed there is nothing that stops a PR agency from misleading the public. But lawyers remain bound by ethical standards and the SRA Principles – they have a duty not to mislead, and acting as an uncritical mouthpiece for claims made by their client is not acceptable.

Did Carter-Ruck really have a legitimate basis for saying that the Italian authorities had misunderstood the business and had their facts wrong? What did Carter-Ruck think they had misunderstood?

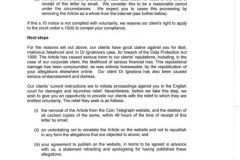

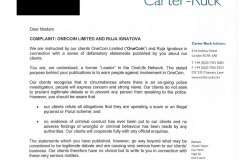

Carter-Ruck’s letter to Jen McAdam

Here is the full text of the letter, which Ms McAdam has kindly permitted us to publish for the first time (PDF version here):

There are, again, a number of curious elements to the letter:

- We once more see the false “confidential” labelling, which I believe was intended to intimidate Ms McAdam into not publishing the letter. It succeeded in this.

- The curious reference to Mr Bjercke “holding himself out as having links to Bitcoin, a competitor cryptocurrency”; perhaps the author thought that Bitcoin was a company or organisation?

- The letter denies Ms McAdam’s accusations that OneCoin is a scam, illegal pyramid scheme or a Ponzi scheme. However it does not say these statements are defamatory. That is very surprising.

- The letter also fails to engage with, or even mention, Mr Bjercke’s evidence that the OneCoin blockchain was faked.

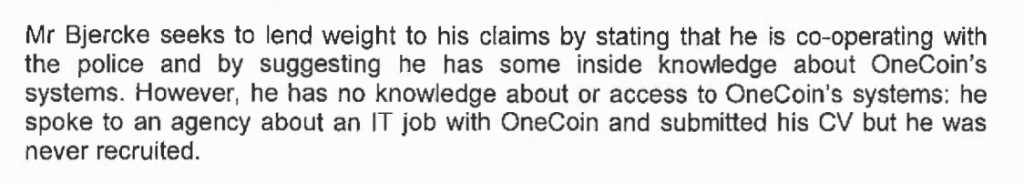

- Mr Bjercke had claimed that OneCoin had attempted to hire him to build a blockchain; he concluded that their “new blockchain” did not exist. Carter-Ruck completely misunderstand or misdescribe his claim:

- Instead, the letter focuses on Mr Bjercke’s conclusion that OneCoin was a criminal network, without referring to his reasons for that conclusion.

- The letter threatened legal action if Ms McAdam did not comply within seven days; it was a pre-action letter. However it failed to comply with the pre-action protocol for defamation. In particular, it objected to the “criminal network” accusation but did not “give a sufficient explanation to enable [Ms McAdam] to appreciate why the words are inaccurate or unsupportable”. That explanation could have consisted with quoting Mr Bjercke’s reasons for concluding that OneCoin was a criminal network, and explained why those reasons were wrong. But instead there was nothing. The letter makes no reference to the evidence cited by Mr Bjercke.

So this was a highly ineffective letter on its face; pursuing ancillary points of detail, missing the main “sting” of the accusations against OneCoin, and breaching the pre-action protocol. Carter-Ruck would have known this.

My view, and that of libel experts I’ve spoken to, is that the letter was not sent as a precursor to legal action. And indeed, when Ms McAdam (impressively) refused to back down, there was no legal action.

So why was it sent? To intimidate an unrepresented person of limited means, and to bluff them into a retraction. It failed.

Legal action against Bjørn Bjercke

There was a parallel attempt in Norway to bring a claim against Mr Bjercke, which went as far as an application to the Norwegian equivalent of a county court. The county court rejected the claim on grounds of complexity, and OneCoin never took the matter further.13My source for this is a discussion with Mr Bjercke.

The Norwegian lawyer acting for OneCoin, Per Danielsen, was struck off last year (following 67 complaints) for acting recklessly against third parties and his own clients, unlawfully using client funds, and breaches of money-laundering rules. Mr Danielsen’s appeal against that decision was rejected earlier this year. During those proceedings, his decision to act for OneCoin was specifically criticised for his lack of due diligence in identifying the potential money-laundering issues.

Mr Bjercke believes that Per Danielsen was instructed by Carter-Ruck. I don’t know if that’s correct, or if there’s a wider relationship between Carter-Ruck and Mr Danielsen, but he is featured on Carter-Ruck’s website, despite having been struck off.

Carter-Ruck write to the FCA

The warning notice that the FCA had placed on its website on 26 September 2016 had been highly effective, warning both potential investors and regulatory/enforcement authorities around the world.

Carter-Ruck wrote to the FCA in late July 2017, demanding that it take down the warning notice. By that time, OneCoin was very near its catastrophic end:14In March 2017 law enforcement agencies from around the world had met at Europol’s offices in The Hague to discuss OneCoin. This wasn’t public at the time, but it explains the subsequent acceleration in worldwide enforcement actions.

- On 14 April 2017, Kazakh authorities had placed the local OneCoin representative under house arrest.

- On 27 April 2017, Germany’s financial regulator issued a “cease and desist” order to OneCoin, requiring the companies to dismantle the OneCoin system, and stop sales and promotion in Germany.

- On 24 April 2017, the Indian authorities arrested 18 local OneCoin representatives and seized $2m in cash from OneCoin’s Indian bank accounts.

- Malta joined the other countries whose regulators were issuing warnings about OneCoin.

- On 9 May 2017, the Hungarian Central Bank published a statement announcing that it would be taking action against OneCoin in coordination with the police, tax authorities and prosecutors.

- On 31 May 2017, the Atlantic published a lengthy article describing OneCoin as a “criminal conspiracy” and detailing the enforcement actions that had been taken against it worldwide. The author wrote “it’s easy to see the lie in OneCoin’s fictional blockchain” which was “led and promoted by known fraudsters waving fake credentials”.

- In June 2017, the Vietnamese authorities announced that the claim by OneCoin’s CEO that OneCoin was licenced in Vietnam was based on a forged document.

- On 9 July 2017, OneCoin’s CEO was accused by the Indian authorities of defrauding investors. The Indian authorities arrested 23 people associated with the business, and issued a warrant for Rjua Ignatova herself.

Again the question should be asked why Carter-Ruck continued to act.

The FCA responded to Carter-Ruck’s letter by taking down its warning notice.

According to the BBC, the initial FCA explanation was that “it had been on our website for a sufficient amount of time to make investors aware of our concerns”. The subsequent explanation was that the decision to take it down had been made in conjunction with the City of London Police, and that – because the FCA does not regulate crypto-assets – it couldn’t take it further.

The FCA is now leaning further into that last explanation, telling TBIJ this was because OneCoin’s activities “did not require regulation”. I don’t understand that explanation; it certainly doesn’t prevent the FCA publishing other warnings about Ponzi and pyramid schemes, or initial coin offerings.15It is also not necessarily the case that OneCoin did not require regulation. Cryptocurrency usually falls outside UK regulatory rules, but in reality OneCoin had no connection to cryptocurrency aside from marketing. Plausibly the correct legal analysis is that OneCoin was a transferrable token issued by a company (OneCoin) – in which case it could well have been regulated in the UK, in the same way as some ICOs. Andrew Penman at The Mirror made this point back in 2020 and I’ve never seen it answered.

It seems a reasonable inference from the timing, and the changing explanations, that the FCA notice was in fact removed as a result of Carter-Ruck’s letter. Carter-Ruck themselves appear happy to take credit for the removal.

Jen McAdam was able to stand up to Carter-Ruck – why wasn’t the FCA?

The end

On 12 October 2017, Ignatova was charged with fraud and money laundering in New York; two weeks later, she vanished.

Things then deteriorated quickly:

- In January 2018, OneCoin’s headquarters in Bulgaria was raided by the Bulgarian authorities, following a request from the German authorities. The Bulgarian authorities said that the company was being investigated in the UK, Ireland, Italy, the United States, Canada, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and elsewhere.

- In July 2018, Ignatova’s co-founder, Karl Greenwood, was arrested in Thailand and extradited to the United States (he pled guilty to fraud and money-laundering charges).

- In March 2019, prosecutors in New York announced charges against Ignatova, and others in OneCoin’s executive team, and arrested its then-CEO, Konstantin Ignatov (Ms Igantova’s brother).

- Other executives have since been arrested; Ms Ignatova remains a fugitive – on the “most wanted” lists of the FBI and EUROPOL.

- In November 2023, the OneCoin head of legal and compliance pled guilty to fraud and money-laundering charges in New York.

This was not a Madoff-style situation where a business starts off legitimate and (for one reason or other) ends up as a fraud. This was a criminal operation right from the start, and emails revealed by US prosecutors make clear that the fraud was not an accident, but Ms Ignatova’s intention.

Why did Carter-Ruck act for OneCoin?

Why did Carter-Ruck feel it was appropriate, or even legal, to act for OneCoin given that:

- OneCoin claimed to be a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin but all the evidence suggested it was not.

- Its advertising promised returns which were impossible.

- There was no evidence of any blockchain (and the supposed blockchain entries on its website had been convincingly shown by Bjork Bjercke and others to be fake).

- The supposed “audit” of a $2bn business by an obscure firm (whose website had disappeared) was redolent of Madoff.

- All of this had led Apex and Bank of New York to conclude in 2016, solely on the basis of public internet searches, that OneCoin was a fraud.

- Events since then made it even more obvious, particularly OneCoin’s blocking of investor withdrawals in January 2017, and the various regulatory and criminal investigations/enforcements across the world.

There are two important reasons why this is different from the usual scenario where a law firm is acting for (or defending) an individual or business accused of behaving unethically or illegally.

First, this was a case where the accusations were that the entire business of OneCoin was a fraud. If the allegations were true, then Carter-Ruck would be receiving the proceeds of crime.

Second, Carter-Ruck would not be conducting a criminal defence of OneCoin – it would be assisting its business by silencing its critics.

Here are some possible hypothetical scenarios for how Carter-Ruck came to act:

- Carter-Ruck might have told OneCoin it was happy to act in principle, but was concerned about the multiple accusations from regulators, journalists, and others that OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme. Carter-Ruck therefore asked OneCoin to provide sufficient documentation to provide Carter-Ruck with assurance that it was a legitimate investment. OneCoin provided documentation that, at least at the time, provided a reasonable answer to the accusations that had been made, and on that basis Carter-Ruck thought it was appropriate to act.

- Carter-Ruck might have asked OneCoin if the accusations against it were true. OneCoin said they weren’t, and denied it was a Ponzi scheme (without any justification or evidence). Carter-Ruck accepted that assertion and proceeded to act.

- Carter-Ruck might have decided that it was in the business of advising controversial clients, and it was not for it to make any judgment about whether the accusations against OneCoin were correct.

- Carter-Ruck might have conducted no due diligence, or inadequate due diligence, and was not aware of the widely reported allegations against OneCoin.

The first of these scenarios could – in principle – have been a perfectly proper way for a law firm to act. No law firm can be expected to undertake a full-scale investigation of a potential client, but there should be a serious assessment undertaken, proportionate to the level of risk. In this case, the high level of risk and the seriousness of the accusations suggest that Carter-Ruck should have applied its procedures robustly. It is conceptually possible that this is what happened but, given the surrounding facts and circumstances, I find it very difficult to see how the conclusion of robust procedures could have resulted in a decision to act for OneCoin.

In my view, the other three scenarios above would represent ethically unacceptable behaviour, and possibly unlawful behaviour. In these scenarios, Carter-Ruck acted recklessly and, as a result, abetted a fraudster.

Of course the reality may have involved a completely different scenario from the four above, but the same question arises in each case: why, given everything that was known about OneCoin, did Carter-Ruck think it was appropriate to act? Did Carter-Ruck miss what BNY and Apex spotted? Or did Carter-Ruck not care?

Carter-Ruck’s decision to threaten defamation proceedings

The decision to act is one thing. The decision to threaten defamation proceedings against Coin Telegraph and Ms McAdam is another.

At this point, Carter-Ruck went beyond merely acting for a potentially criminal business. It was sending an aggressive communication to unrepresented individuals. If OneCoin was a fraud, its motivation in instructing Carter-Ruck to send these letters would be to protect its fraud from scrutiny, and enable it to continue to defraud investors. This should have been regarded by any law firm as a very high risk situation.

A meritless factual claim

What steps, if any should Carter-Ruck have taken to establish that the accusations were false?

One view is that Carter-Ruck had no duty to take any steps. If a client instructs it to make a factual assertion in correspondence to the other side, it may do so, and perhaps is even required to do so. In many ordinary cases this may be a respectable position to take; I don’t think it’s defensible in this case.

I’d suggest that the extent to which a firm is required to check factual points depends upon the likelihood that, by making those points, it will be misleading a court or a third party (such as Ms McAdam or Coin Telegraph). In this case there was, at the time, a high risk that the factual claim by OneCoin (“we are not a Ponzi scheme”) was false, and therefore a high risk that Carter-Ruck would be misleading Coin Telegraph and Ms McAdam (and, indirectly, the wider public). A solicitor’s duty to uphold the rule of law, act with integrity, and maintain the public trust meant that Carter-Ruck should have considered the matter extremely carefully before writing as it did.

The evidence of those letters, and the content of those letters, suggests that Carter-Ruck did not consider the matter carefully. It seems reasonably likely they did not conduct even basic background research into cryptocurrency, OneCoin, or the accusations. If that’s right, then Carter-Ruck’s decision to send the letters was even more reckless than its original decision to act.

Everyone has a right to a criminal defence, and a criminal lawyer is perfectly entitled to run a factual defence that the lawyer may privately regard as far-fetched (provided the lawyer does not positively know the defence is false). That does not apply to civil litigation. SRA guidance is clear that lawyers may not run meritless claims. This applies to meritless factual claims in the same way as meritless legal claims.

The FCA letter

More serious issues arise from Carter-Ruck’s decision, three months after their letter to Ms McAdam, to write to the FCA to request that it take down its warning notice. I say “more serious” for two reasons:

First, by this time it should have been clear to a reasonable observer that OneCoin was fraudulent – countries were starting to arrest OneCoin employees, and India had an arrest warrant out for Ms Ignatova herself.

Second, the letter to the FCA had more impact. Ms McAdam and The Coin Telegraph did not take down their postings; but the FCA did take down its warning notice. That plausibly facilitated the continued fleecing of “investors” by OneCoin until the whole enterprise exploded three months later. This was a very foreseeable outcome, and presumably OneCoin’s intended outcome. Carter-Ruck’s recklessness had consequences.

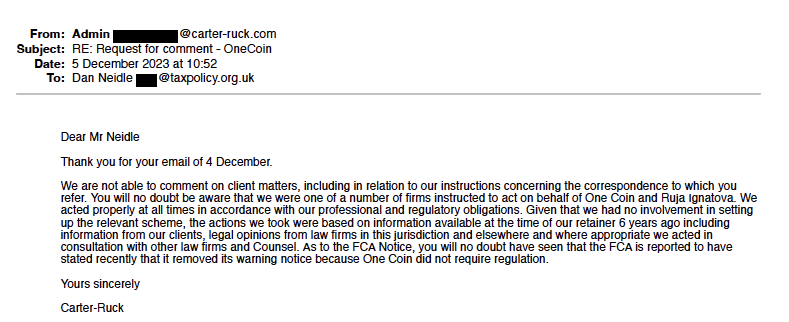

Carter-Ruck’s response

I asked Carter-Ruck why they acted for a client which public sources, at the time, indicated was likely involved in criminal activity. They refused to comment, citing legal privilege:

Carter-Ruck say they acted based on information available at the time. If that included the information set out above then Carter-Ruck’s decision to act is hard to defend. If it didn’t, then Carter-Ruck’s client due diligence procedures were inadequate.

Their other points are unconvincing:

- Nobody has accused Carter-Ruck of setting up the scheme. I’m not sure why they think this is relevant.

- The fact other firms may have acted is problematic for those firms, and hardly a defence for Carter-Ruck. However, as far as I’m aware, Carter-Ruck was the only UK firm which sent letters to unrepresented individuals threatening libel proceedings for accusing OneCoin of being a fraud.

- The content of the “legal opinions in this jurisdiction and elsewhere” is a mystery. I doubt very much they were opinions that considered the allegations of fraud (legal opinions cover the law, not factual matters). More likely they were opinions that OneCoin’s pretended business of offering training courses and a cryptocurrency did not fall foul of securities rules and/or prohibitions on pyramid schemes. If so, this is again not relevant – Carter-Ruck should have been on notice of OneCoin’s actual business of defrauding its investors.

- The reason why the FCA agreed to remove its warning notice is important but once more not relevant: the impetus for the removal was Carter-Ruck’s letter to the FCA, and Carter-Ruck should not have sent that letter.

Finally, the usual prohibition on commenting on client matters does not apply here. OneCoin was a fraud, right from the start. Even if Carter-Ruck had done nothing wrong, and had no way of knowing that they were furthering that fraud, that wouldn’t change the fact that they were furthering the fraud. Legal privilege and confidentiality do not apply in such circumstances. Unlike other recent cases, this isn’t just one transaction which is alleged to be fraudulent; it’s a business where the entire executive team is now either in jail or has disappeared. The man who instructed Carter-Ruck, Frank Schneider, is himself on the run.

I put this point to Carter-Ruck. They did not reply. A copy of my email requesting comment is here.

Lawyers understandably don’t disapply privilege and confidentiality whenever an accusation of fraud is made, but this is the rare case where there is no doubt that OneCoin’s business was entirely fraudulent. Carter-Ruck’s refusal to comment is therefore in my view self-serving.

The consequences for Carter-Ruck

I cannot recall a case where a law firm acted for a client whose business was entirely fraudulent, where that was widely understood at the time , and where the effect of the law firm’s involvement was to assist the fraud. It seems inconceivable Carter-Ruck knew that OneCoin was fraudulent, but all the signs were there. Carter-Ruck’s actions throughout were reckless, and that had serious consequences.

Carter-Ruck appears to have breached the SRA Principles on multiple occasions. In particular:

- The original decision to act, given the available evidence that OneCoin was fraudulent (evidence that warned off BNY and Apex).

- The decision to continue to act, as evidence piled up that OneCoin was a fraud.

- The lack of thought and research that went into the letter to Coin Telegraph showed a high level of recklessness. The fact that Carter-Ruck didn’t know what a Ponzi was, and so didn’t see that their own facts showed OneCoin to be a Ponzi. The denial that OneCoin was connected to Messrs Greenwood and Allan (which one Google search would have revealed was false and misleading). The inclusion of a false “confidentiality” heading in the letter.

- The decision to write to Jen McAdam, an unrepresented individual of limited means, with a false “confidentiality” heading that served to intimidate, when their letter breached the pre-action protocol and failed to engage with the actual evidence presented by Mr Bjerke that OneCoin was fraudulent. Did Carter-Ruck at that point have any legitimate basis for contesting Mr Bjercke’s allegations?

- Carter-Ruck’s decision to act as a PR firm and claim that actions of the Italian Competition Authority was based on a misunderstanding and incorrect facts. It wasn’t – it was based on an entirely correct understanding. What led Carter-Ruck to think otherwise? Or did they just issue their statement without any consideration of whether it was correct?

- The decision to write to the FCA at a time when the evidence OneCoin was a fraud was overwhelming. What was the content of that letter?

- All of this showed a lack of integrity. It also breached the specific rule that a solicitor “can only make assertions or put forward statements, representations or submissions to the court or others which are properly arguable”. The statements in Carter-Ruck’s letters were not properly arguable.

There are also uncomfortable questions for two other firms, Locke Lord16The SRA may already have investigated Locke-Lord following the conviction of Mark Scott (although I don’t believe he was a partner in their UK firm) and following the revelation that a UK corporate lawyer from Lock Lorde was still writing to Ms Ignatova as late as June 2018 (see chapter 32 of The Missing Cryptoqueen). and Hogan Lovells17 These extracts from a Hogan Lovells opinion (if genuine) show a disappointing failure to step back and appreciate the “big picture” of what was going on – this was March 2017, and there was already good reason to be highly suspicious of OneCoin. Some of the recommendations in the opinion were unreal; and signs that OneCoin was a pyramid/Ponzi were noted, but then there was a failure to realise what this meant. It is important to note that these two firms were not making accusations of defamation against people criticising OneCoin – Carter-Ruck should be held to a higher standard.18On the other hand, it is unclear how both firms’ due diligence failed to identify the obvious problems with OneCoin (both firms are AML-regulated).

I’ll be asking the SRA to consider these issues.

I’ll also ask the SRA to provide guidance to solicitors on the general question of the extent to which lawyers are required to verify factual matters before asserting them in civil litigation, or correspondence relating to potential civil litigation.

It appears from a number of recent cases that some defamation lawyers believe that they have no responsibility to verify factual claims by their clients, even when the claims are far-fetched. There’s a strong case for reforming defamation law, but on its own that won’t solve the problem. Lawyers would continue to make meritless legal and factual claims, with a reckless disregard as to whether they are true. There is a strong public interest in changing this behaviour; a high profile SRA intervention is the only way I can see this happening.

I wouldn’t have been motivated to look into OneCoin without Ed Siddons and Matthew Valencia‘s article for The Bureau of Investigative Journalism – many thanks to them. And thanks to Andrew Penman, former Daily Mirror columnist, probably the first journalist in the UK to write about OneCoin, who drew my attention to Carter-Ruck’s PR activity.

I’m very grateful to Jen McAdam and Bjørn Bjercke, who generously spent time talking me through their experiences.

As ever, I am completely reliant on the expertise and goodwill of legal experts across the profession. Thanks to Y and T for defamation law advice, P for criminal law input, A for data privacy advice, and G for an invaluable discussion on law firm client due diligence. Professor Richard Moorhead kindly reviewed an early draft from a legal ethics standpoint.

For anyone interested in reading more about OneCoin, I strongly recommend The Missing Cryptoqueen by Jamie Bartlett, and Devil’s Coin by Jen McAdam. There’s plenty more to be said – those books came out too early to pick up the latest New York trial evidence (Jamie has added an addendum-of-sorts here). We may see some of that in a documentary on OneCoin which Bjørn Bjercke has been working on, and is due to be released in 2024 – trailer here.

Thanks also to Trustnodes for their article, and for kindly fixing what was previously a dead link to the Carter-Ruck letter to Coin Telegraph.

Photo by Ronny Martin Junnilainen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

-

1The “training courses” being an attempt to evade prohibitions on pyramid schemes that don’t actually sell products, and securities regulations that in many countries would prohibit direct sales of OneCoin

-

2A side note: Ms Ignatova claimed to have studied European law at Oxford University. A poor quality scan of a degree certificate is available, which purports to show her having studied at St Hilda’s, and received a Magister Juris. There’s an open question if her Oxford qualification is genuine; media reports generally report her degree uncritically, but sources from St Hilda’s are sceptical she was there. I’ve asked St Hilda’s if they can confirm, and I’ll update this if I hear back.

-

3The nature of many law firms’ work means they are also covered by anti-money laundering rules, which require more onerous procedures. I expect Carter-Ruck are not in scope of the AML regulations, and therefore this article assumes they were only required to undertake more basic due diligence.

-

4OneCoin published a somewhat odd video of Ms Ignatova interviewing the senior partner of Semper Fortis. It comes as no surprise that the audit turned out to be have been written by OneCoin staff.

-

5Source: data from Yahoo Finance, chart by Tax Policy Associates Ltd. You can see a more conventional chart of the Bitcoin price here; no amount of cherry-picking dates will create a result like the OneCoin chart.

-

6There is much more about this in Jamie Bartlett‘s book, however the Kreisbote article is probably all that would have been easily found by a desktop search exercise in 2017. That should have been enough to raise a red flag.

-

7which we’ve made available in more readable form as a PDF here

-

8I suppose a possible defence is that “we just said they weren’t directors and that is correct – they weren’t directors”. But if that was indeed the rationale, then this was a deliberate attempt to mislead.

-

9As this was 2016, the pre-GDPR position applied

-

10I haven’t been able to locate it; the link given by Carter-Ruck was https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OmQtWRd_FqU, but that link is now dead

-

11“onecoin ponzi”, “onecoin fraud” and so on. I didn’t use any terms which relied upon post-2017 knowledge, e.g. the names of the entities later discovered to be laundering the funds

-

12This is all from Spendiff’s testimony at Scott’s trial for money-laundering. I can’t find a primary source, but there is a good summary in this Twitter thread (unrolled here) and in Jamie Bartlett‘s book The Missing Cryptoqueen

-

13My source for this is a discussion with Mr Bjercke.

-

14In March 2017 law enforcement agencies from around the world had met at Europol’s offices in The Hague to discuss OneCoin. This wasn’t public at the time, but it explains the subsequent acceleration in worldwide enforcement actions.

-

15It is also not necessarily the case that OneCoin did not require regulation. Cryptocurrency usually falls outside UK regulatory rules, but in reality OneCoin had no connection to cryptocurrency aside from marketing. Plausibly the correct legal analysis is that OneCoin was a transferrable token issued by a company (OneCoin) – in which case it could well have been regulated in the UK, in the same way as some ICOs. Andrew Penman at The Mirror made this point back in 2020 and I’ve never seen it answered.

-

16The SRA may already have investigated Locke-Lord following the conviction of Mark Scott (although I don’t believe he was a partner in their UK firm) and following the revelation that a UK corporate lawyer from Lock Lorde was still writing to Ms Ignatova as late as June 2018 (see chapter 32 of The Missing Cryptoqueen).

-

17These extracts from a Hogan Lovells opinion (if genuine) show a disappointing failure to step back and appreciate the “big picture” of what was going on – this was March 2017, and there was already good reason to be highly suspicious of OneCoin. Some of the recommendations in the opinion were unreal; and signs that OneCoin was a pyramid/Ponzi were noted, but then there was a failure to realise what this meant.

-

18On the other hand, it is unclear how both firms’ due diligence failed to identify the obvious problems with OneCoin (both firms are AML-regulated).

12 responses to “Carter-Ruck: how the UK’s best known libel firm recklessly acted for a $4bn fraudster”

As many of you know, I am the defendant in what I believe to be two SLAPP cases, both connected to an infamous property trainer who’s been in the headlines this week for all the wrong reasons.

The two solicitors involved did not appear to do any due diligence of the clients.

In the second case, the claimant created a highly defamatory and malicious CrowdJustice page to raise the funds to sue me. The page did not give anything like a true representation of what had happened and made all sorts of unsubstantiated & harmful accusations against me.

I wrote to the claimant’s solicitors pointing out that the page bearing their name was defamatory and malicous and they ignored me. They could have told their client that they refused to be associated with such false claims and he should amend the page, but they didn’t.

The behaviour of both sets of solicitors throughout has been truly awful with many abuses of court processes in my opinion.

I reported both to the SRA and are awaiting their verdict, but I don’t hold out much hope.

I am truly grateful to Dan Neidle for his continuing exposure of all the damage done by SLAPPs and it seems he is solely holding these SLAPP solicitors to account. Until something is done about SLAPPs, they will continue to be used by wealthy people – mostly men – to stifle public interest commentary and thereby control the on-line narrative.

The SRA needs to get a lot tougher on this matter and articles like Dan’s will hopefully aid the process of SLAPPs being stamped out.

[edited at Vanessa’s request to correct a typo]

So, is there any reason why the FCA should not publish the SLAPP letter it received, so that people can make up their own minds as to the most likely explanation?

great question

Sounds like a candidate for a Freedom of Information request…

Excellent investigation, many thanks Dan.

Firms like Carter Ruck will only start acting lawfully once (a) they have incurred severe, solvency-threatening fines; and (b) every individual partner and associate has been prosecuted by the SDT, and publicly struck off.

As the late Charlie Munger warned: “Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.”

SRA, over to you. Along with all of the Post Office solicitors, you have a lot to be getting on with.

Dan

Thanks.

Pleased to see you will “be asking the SRA to consider these issues”

I consider and would hope the integrity of not just Carter-Ruck but also all those professionals in the firm who were involved in decision making is urgently considered by their regulators and the outcome widely published without redaction.

Very interesting. Mr Bartlett and the BBC did a podcast series on this fraud. It’s on Iplayer for UK listeners and in rss feed podcast apps under the search term The Missing Crypto Queen, I don’t think the latter is geo-fenced.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/brand/p07nkd84

Do you know if CR tried it on with Mr Bartlett?

Well done on a very detailed exposé of Carter Ruck. As a reader of Private Eye, I have often seen articles about a law firm with a similar name – Carter Fuck. I wonder if they are related?

See this also:

“2.4 You only make assertions or put forward statements, representations or submissions to the court or others which are properly arguable.”

https://www.sra.org.uk/solicitors/standards-regulations/code-conduct-solicitors/

thank you – I should add that. Quite a few people seem to believe solicitors can put forward any old crap.

Excellent article, many thanks for posting

I’d be fascinated to hear more (at the appropriate time) about your various dealings with the SRA.

Does it engage? listen? follow up? I’d expect your reports contain rather more detail than many that it receives.