It’s a common complaint that the UK tax system is much too complicated. That complaint is correct.

Some of the complication is inevitable (modern life is complicated). Some is a response to avoidance. Some is driven by policy choices (e.g. VAT exemptions1Once you decide restaurants have to charge VAT at 20%, but ingredients should be 0%, you are on a one-way road paved with Jaffa Cakes and giant marshmellows). But some of the complication really is unnecessary. I’ll try to demonstrate the problem by taking one tax point that faces many companies investing in the UK, and working through each of the overlapping rules the company has to work through.

Judge for yourself how sensible those rules are, and how many are really necessary.

The scenario

Let’s pick a simple scenario that’s realistic – indeed very common:

- Waystar RoyCo is a large US business establishing a new UK subsidiary, Waystar UK.

- It has a finance company in the US (Waystar Finco) which raises money from the market (borrowing from banks, issuing bonds etc) and then makes it available to group companies.

- Waystar Finco wants to provide some of that funding to Waystar UK.

- So Waystar Finco makes an “intragroup loan” to Waystar UK, with an interest rate reflecting the cost of Waystar Finco’s funding plus Waystar Finco’s own admin etc costs.

Like most businesses, Waystar UK will expect to get UK corporation tax relief for its interest payments.2I’m only covering interest deductibility and not withholding tax, VAT, or any of the other issues the arrangement would raise. Will it?

From a policy perspective Waystar UK absolutely should get tax relief. It would if it borrowed directly from the market, and interposing Waystar Finco should make no difference (but is likely cheaper/more efficient for Waystar). But that rightly cuts no ice with HMRC – the question is, what do the rules say?

There are many, many, rules that can impact tax relief/deductibility of interest. Here’s how I’d advise Waystar UK on the main ones, with added commentary on whether each of the rules really still makes sense.3Like most lawyers, I was truly an expert in a very narrow field, had reasonable knowledge across a wider area, and no more than passing familiarity with anything else. Most Tax Policy Associates content is in areas where I was not truly an expert, and so I am entirely reliant on the generosity and expertise of many current and retired professionals. However the issues discussed in this article are ones where I had direct expertise. They are therefore very relevant to my past clients, but I have no financial relationship with those clients (or my former law firm, aside from my pension).

1. Transfer pricing

Most countries in the world have “transfer pricing” rules. In broad terms, they say that if a company has an arrangement which isn’t on “arm’s-length terms” and it’s taxed as if it was. So if, for example, current market interest rates are 6%, and Waystar UK borrows from Waystar Finco at 10%, then it will only get a deduction for the 6%. This is pretty sensible.

The UK has a reasonably standard implementation of the standard OECD rules – they’ve been around for ages and are well understood.

Advice: Waystar UK needs to be careful of the rate it borrows under, and should be able to justify that the rate is comparable to the commercial borrowing rate it could get in the market, plus a small commercial fee for Waystar Finco’s role arranging the finance. So if Waystar UK has zero assets it will not be able to borrow anything; if it has £1bn of assets it should be able to support a £200m loan. The maximum of debt it can support is a question of fact, on which Waystar’s own finance people can form a judgment.4And create and retain appropriate transfer pricing documentation. They could instruct a transfer pricing expert to prepare a report, but that is probably unnecessary; the more pragmatic approach is for Waystar UK to approach banks and obtain quotes as if it was borrowing itself. This will all be a few pages of advice.

Conclusion: These are international rules which the UK can’t realistically change on its own. They work well.5At least when applied to debt, where it’s easy to establish an arm’s length interest rate. More problematic when it comes to arrangements that have no obvious market equivalent. Keep them.

2. Corporate interest restriction

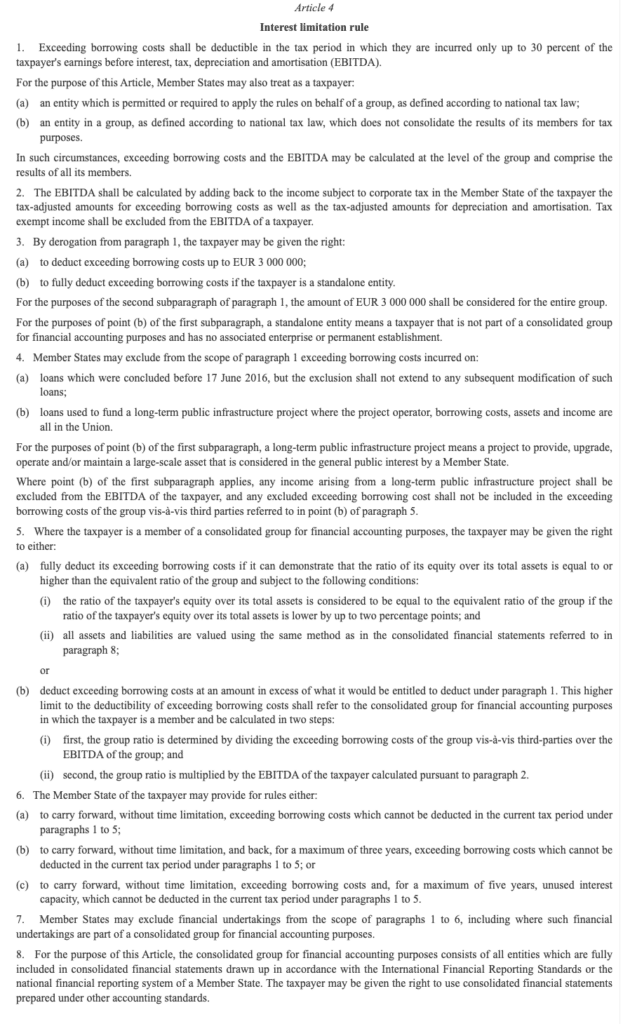

in 2015, as part of its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, the OECD created a set of rules which limit the amount of interest deductibility companies can claim.

Most developed countries adopted some variant on the rules – here’s a helpful map from the OECD:

The basic idea is simple: if you’re borrowing from a genuine third-party, like a bank or the bond market, there’s no restriction. If you’re borrowing from a related party, then you lose deductibility once your interest cost exceeds 30% of your EBITDA.

Here’s the EU implementation, part of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive:

Here’s the UK implementation:

no images were found

134 pages6I was lazy; this is the original text. It’s since been amended, and is longer.

That obviously isn’t enough, so there’s also 200 pages of detailed guidance.

You might ask what magic the EU performed in order to squeeze hundreds of pages into just two. There was no magic: it’s just a difference in approach to drafting rules. Civil law jurisdictions generally draft on the basis of broad principles. UK legislation generally provides detailed rules, catering for every possible circumstance.

There is a good argument that the classic common law approach creates certainty of application, which is particularly important in tax. However, by the time you have hundreds of pages of legislation and guidance, certainty has long since left the building. Complexity has become a source of uncertainty. And this isn’t a one off – the last decade has seen a series of new rules, each more complex than the last.

Businesses struggle to achieve the “obvious” result from the rules. HMRC struggles to apply them. 7In particular, the “group ratio rule” and the “public infrastruture election” are incredibly complex in practice and often don’t work as intended.

We should stop being so dogmatic, and adopt a principles-based approach when that is going to be easier for both business and HMRC to apply. Professor Judith Freedman has written persuasively on this point.

Advice: in theory this should be fine given that Waystar Finco is ultimately borrowing from the market, but the detail will take a significant amount of work. Easily 15 pages of analysis.

Conclusion: scrap the UK rules and guidance and adopt a simpler EU-style approach.

3. Hybrid mismatch rules

Here’s a classic way to avoid tax: cunningly craft the Waystar Finco/Waystar UK loan so that the UK tax system thinks it’s a loan, but the US tax system thinks it’s a preference share, or even doesn’t exist at all. The result? Tax relief in the UK, and either no tax in the US or even, if the CEO is greedy, tax credits. The loan is a “hybrid” – taxed differently in two different countries.8This is a considerable simplification. There are many ways to create hybrids, and certain features of the US tax system means it is particularly well-suited to the task

The hybrid rules were created to stop this kind of thing – they’re another part of the BEPS Project. That yielded 39 pages of really difficult legislation.

And OMG the guidance:

no images were found

484 pages.

I don’t want to be unfair to HMRC here. The horribleness of the legislation means people begged HMRC to clarify this point, that point, and the other point, and before you know it: 484 pages. I believe the longest guidance ever created by any tax authority in human history for one single tax rule.

Most of the time, HMRC ignores the rules entirely, and only actually cares when it sees something avoidancey – but, for large loans, and large risk-averse businesses, you can’t count on that. So expensive advisers (me, in a past life) occasionally spend weeks locked in a dark room making sure that highly complex, but innocent, structures aren’t caught. That same complexity means that guilty structures can sometimes escape scot-free.

Advice: Waystar’s commitment to high ethical standards mean it’s inconceivable they’d try to create a hybrid. But US tax rules, and typical US corporate structures, are so complicated that I can’t just assume the rules won’t apply. Significant time will need to be spent analysing the whole structure, with US tax and accounting input. This is potentially a big job.

Conclusion: Again, principles-based drafting is the answer. The EU rules are about 13 pages, split between ATAD and ATAD 2. Let’s do that.

4. Reasonable commercial return

Paragraph E of section 1000(1) CTA 2010 denies a deduction if securities are “non-commercial”, defined as follows:

This is a pretty reasonable rule. But why does it exist? If the securities are paying more than a reasonable commercial return, they can hardly be at arm’s-length, so the transfer pricing rules would be engaged. Wouldn’t they?

It’s not that easy, and I could write a 10 page memo on the subtle differences between the two tests,9One practical example; say market rates today, when the Waystar UK loan is created, are 6%. In two years time, rates are 3%, and Waystar amends its finance documentation to e.g. comply with some new regulatory rules. That may mean the loan is a “new loan” and “reasonable commercial return” needs to be assessed again. The problem is: 6% is no longer a “reasonable commercial return”, and half the interest therefore becomes non-deductible. A well-advised company will make the amendment in such a way that there won’t be a new loan, but a company that doesn’t seek advice could make an expensive mistake. Counter-intuitive “gotchas” like this are not a feature of a healthy tax system. but that memo should not exist. We don’t need two rules doing almost exactly the same thing.

My excerpt above could mislead you into thinking section 1005 is just a simple one sentence rule. There are, however, nine lengthy sections that follow, putting various glosses it. My favourite: section 1013 is an exception to an exception to an exception to an exception to s1005.10I am not exaggerating: s1007 is an exception to s1005, s1008 is an exception to s1007, then s1012 is an exception to section s1008, and s1013 is an exception to s1012. Yes, “exception” is a slight over-simplification, but that makes things worse, not better

Advice: the easy approach is for me to say to the client that everything is fine provided the interest under the loan is no more than a “reasonable commercial return”. But the client will probably ask what that means, and how it’s different from the transfer pricing test. Cue a lengthy memo, and an unhappy client walking away with the distinct impression that the UK is not a great place to do business.

Conclusion: abolish the rule. If parties are related then it adds nothing to transfer pricing. If parties aren’t related then the rate should de facto be commercial; if it isn’t then something weird is going on, which one of the approximately gazillion anti-avoidance rules will surely counter. “Reasonable commercial return” is a fossil, and belongs in a museum.

5. Results dependency

Here’s Condition C section 1015:

“Depends on the results of the company’s business” is a test that used again and again in tax legislation. So it’s a bit sad that nobody knows what it means.

There is a sensible meaning: “don’t pretend something’s a loan when it’s really shares, just so you can get a tax deduction”. Do we really need a rule like that? Wouldn’t one of the other many, many anti-avoidance rules kill something as obvious as dressing equity up as debt?

It’s worse, because there’s also a crazy meaning. HMRC think Condition C also means: “don’t create a loan where the borrower only has to pay interest if it can afford to pay interest”. This is often called a “limited recourse” or “non-recourse” loan. And HMRC say you can’t do it.

That’s a problem, because there are many commercial scenarios in which you want limited recourse funding, particularly if you have multiple projects (power stations, housing developments, investments) where each is funded by a different lender.

From a policy perspective, I’ve no clue why HMRC think this is a bad thing. Every other country in the world, I believe, permits it.

HMRC’s approach has two consequences. First, it’s super easy, barely an inconvenience, to get around the rule by establishing each new project in a new company. Second, if you can’t do that, or it’s too much effort, you just go to another country. So this is a rule that serves no purpose, creates complexity, and pushes business out of the UK. Excellent.

Advice: should be fine. Although, like many advisors, I’ve often seen loan documents where some helpful US advisor added a non-recourse clause at the last minute, not realising that it would mess up the tax. Another dangerous and pointless “gotcha”.

Conclusion: abolish the rule – it’s a fossil from the days when avoidance was easy. Make clear in guidance that any debt which really behaves like equity is, by definition non-arm’s length, and will lose deductibility under the transfer of pricing rules. But limited recourse shouldn’t offend anyone.

6. Equity notes

Section 1006 bars deductibility for an “equity note” (meaning, broadly, a security that can stick around for longer than 50 years) if it’s held by an “associated person” or someone funded by an “associated person”.

US companies have sometimes issued 100 year bonds. Perhaps Waystar Royco wants to, and then lend the proceeds into the UK?

Well, tough – the equity note rule means it can’t.

Why? I’ve no clue. If it’s a market instrument, and satisfies the transfer pricing rules, then what’s the problem with having a very long term? This is an obscure rule, and I’ve occasionally seen it catch people out.

Advice: don’t have a term of 50 years.

Conclusion: another fossil – abolish it.

7. Section 444

Remember the transfer pricing rules? Spot the difference between that, and this:

A completely unnecessary rule which creates complexity and uncertainty (not least because working out the consequence of that “independent terms assumption” is hard). It shouldn’t apply where the transfer pricing rules potentially apply, but there are weird scenarios where you’re not sure which case you’re in.

Advice: in this case reasonably clear it won’t apply. In other cases, that’s more difficult, but probably yields the same result as the transfer pricing result. If you want better than “probably”, that memo will cost £5,000.

Conclusion: scrap s444.

8. Anti-avoidance counteraction

Debt is taxed under the “loan relationships” regime, which contains a broadly drafted anti-avoidance rule:

And then:

So if you get a tax advantage in a way that’s contrary to the principles of the rules, then… you don’t.

The precise scope of this is unclear, but that’s not a bad thing for an anti-avoidance rule – it means people have a powerful incentive to steer clear of grey areas.

Advice: yes, one of the reasons to choose to fund Waystar UK with debt rather than equity was to get a tax deduction for the interest. Waystar could have funded with equity; that would have meant more tax. But I would say the “principles” of the rules envisage a choice between equity and debt, and so s455C doesn’t apply. This will run to several pages of analysis.

Conclusion: all tax regimes need an anti-avoidance rule of some kind,11When the general anti-abuse rule (GAAR) was introduced, some thought that meant we could have a bonfire of the TAARs (targetted, as opposed to general, anti-avoidance rules). But a lot of avoidance falls short of “abuse”, so it’s not surprising this didn’t happen and this is a pretty good one.

9. Unallowable purposes

There’s a much older anti avoidance rule in section 442:

and

This rule therefore does two things:

- If debt is borrowed for a non-business purpose then interest is not tax-deductible. So, for example, there’s a problem if Waystar UK is going to use all the funds to buy a yacht for its chairman. Fine.

- And if the main purposes include a “tax avoidance purpose”12The rule was introduced when the regime was created in 1996. It was then paragraph 13 Schedule 9 Finance Act 1996, and old cases and old advisers still refer to it as “paragraph 13”. Its ways were mysterious and unknown for a long time, but there have since been a number of cases. then the interest is not tax-deductible.

The fact the test assesses subjective “purpose” has an important but odd consequence.

Say that Wayco’s CFO sends a memo saying “hey, let’s use debt to get a juicy tax deduction”. There’s a clear tax main purpose and s442 applies.

Say that Wayco’s rival PGM establishes a precisely identical structure, but their CFO’s memo doesn’t mention tax (and instead speaks of the convenience of extracting profits through interest payments). Then it’s looking much better.

A rule that treats two identical businesses differently is not a good rule. A rule that can be beaten by carefully controlling communications13Yes technically the rule looks at the “purpose”, and that’s in hearts and minds not just documents, but in the real world contemporaneous documentation is critically important. Particularly given the length of time between a transaction and any future court appearance, which renders memory unreliable. is a terrible rule.

HMRC’s guidance acknowledges the uncertainty for intra-group loans here.

Advice: something like “You have told me the debt is being advanced for commercial (i.e. non-tax) reasons, the tax benefit of interest deductibility is ancillary and you would have lent to the UK even if there was no deduction. On that basis section 442 won’t apply”

Conclusion: we don’t need two overlapping anti-avoidance rules in the loan relationship regime. s442 did valuable duty for many years, but should be put out to pasture.

The cost

This complexity has a cost. HMRC and advisers spend money building expertise to police it. Clients pay lawyers and accountants large sums to advise on it. This is not a good use of anybody’s resources, and it makes the UK a worse place to do business.

I’m convinced we wouldn’t lose £1 in tax revenues if we scrapped/dramatically simplified the seven bad rules above (and put HMRC’s freed-up resources into anti-avoidance).

And this is just one tax question for one common business structure. There are dozens more areas just as ripe for simplification.

The first step would be the easy one: identify and repeal the “fossils”.

The second step, moving towards principles-based-drafting, would be significantly harder – but we can’t continue as we are, with hugely complex new rules added every few years. Let’s stop making generic complaints about tax complexity, and tackle some of the root causes.

5 responses to “The reality of tax complexity, and how to fix it”

When I started doing tax – the best part of 25 years – almost all of the UK’s tax legislation came in three volumes. Two for direct taxes, one for indirect taxes. I wish I had kept them.

I have watched as the annual books – Red and Green in bygone days, now Yellow and Orange – have got incrementally longer, year after year. More volumes with thinner paper and smaller type,

It wasn’t necessarily easier then – the old Capital Allowances Act 1990 was a dense thicket, for example – but I don’t really understand why the legislation needs to be several times longer now. Part of it can be attributed to the tax law rewrite, which was meant to make the legislation easier to read and understand but often just made it longer Meanwhile governments of all stripes have continued to tinker and add chunks year by year.

We are well past the point of needing to burn it all down and start again. But let me retire first!

Interesting that you identify Common Law with detailed rules and Roman Law with principles.

For Accounting Standards, IFRS (originally largely based on UK ideas with some allowances for continental Europe approaches that were whittled away over time) were principles, while US GAAP was detailed rules.

Continental European countries (at least the Catholic ones) were fairly detailed rules (from tax legislation)

Unfortunately with time IFRS has become almost as detailed as US GAAP, driven largely by the need for “anti-avoidance”.

Remoaner roman law style regulations in our fine common law thingamy? What is this popish plot? The tax avoidance directive is not a regulation, its direct effect is limited so one may find (I say “may” because I have no idea) that its integration into national tax codes is rather more complex than that shown above. If it is as long as ours then the lobbying effects of tax advisors etc are in fine shape. Good for them! Attempting certainty and keeping tribunal and prosecution activity to a minimum is, as you say, germane to our system. Are you suggesting we change this to accommodate areas of legislation where complexity increases exponentially, or at least quite a lot?

Definitely agree with all the specific rule changes you propose, although at least the short-term impact of shifting to a principles based approach would likely be more uncertainty while the courts decide points where HMRC and tax payers disagree on how any particular principle should be applied. It should be possible to rewrite concise versions of the anti-hybrid and corporate interest restriction rules and guidance without a full shift to a principles based approach, especially (as you say) if those are supported by effective, generic anti-avoidance rules. One major simplification your suggestions raise is also to have a generic schedule of definitions for a number of commonly used (or at least not substantially different) terms across tax legislation. there is no good reason I can see to include a separate definition of ‘related persons’ and ‘control group’ in the Hybrid Mismatch rules when there is a perfectly good definition of ‘related parties’ that covers the same points already in both CTA 2010 and ITA 2007.

Of all the many excellent crossover references I have caught whilst learning about tax from this blog, the Pitch Meetings one is possibly the most surprising. Tight!