The “carried interest loophole” means private equity executives pay tax at the low, low, capital gains rate of 28%, and not the 47% rate that an equivalent banker would pay. Earlier this year I wrote a slightly controversial paper, published in the British Tax Review, which suggested that the loophole didn’t actually exist. I said that the 1987 agreement between the DTI, Inland Revenue and British Venture Capital Association (which created the loophole) got the law wrong, and it was unlawful for HMRC to stick to it.

The Good Law Project brought legal action against HMRC using these arguments. That has now ended. The Good Law Project say it’s won. HMRC say nothing’s changed.

Who’s right?

Carried interest

Private equity executives take a special interest in the funds they manage – “carried interest”. It’s very different from the investments that third parties make in their funds, because they don’t pay for it1Or they pay a very small amount. Or they pay a larger amount, perhaps even as much as 5% of the total capital of the fund, but that is provided by a non-recourse loan which means they’re not actually out fo pocket. Either way, the executives are getting a deal that isn’t available to anyone else.. But if the fund performs past a pre-determined “hurdle”, then the carried interest usually pays out 20% of everything over the hurdle. For a successful fund that can be multiple £100m, shared between a relatively small executive team.

Bankers receiving bonuses pay income tax/NI at the full marginal rate of 47% – and the bank pays employer national insurance at 13.8%. But private equity executives receiving carried interest are taxed at 28%.

The reason goes back to 1987.

The 1987 deal

In 1987, the British Venture Capital Association reached a deal with the Inland Revenue (as it was then) and the Department of Trade and Industry on how private equity funds were taxed.

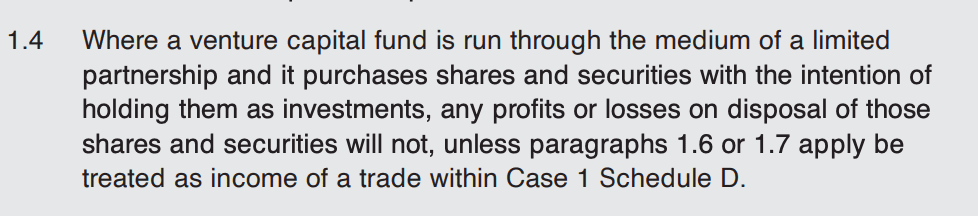

Here’s the key paragraph:

This created the “carried interest loophole”.2Not really a loophole; because that and successive Governments have known and approved of it. However that’s the term often used, and so I’m afraid I will use it in this article. My apologies to purists. As long as the fund is structured as described in the statement, and the executives say their “intention” is to hold the fund’s shares etc as investments, the fund is not “trading” (a key tax concept). Meaning that executives get capital gain treatment on their return when the fund performs – their “carried interest”.

It’s this that enables private equity executives to pay tax at a lower rate, because (at least for now) the rate of capital gains tax is so much lower than the rate of income tax. Overall, the “loophole” is worth over £600m a year to private equity fund managers.3The source for the £600m figure is this FOIA, which shows £3.4bn of gains in the most recent tax year. The difference between CGT and income tax/NI on £3.4bn is £600m. This will be a significant under-estimate, because it doesn’t include the very substantial amount of unremitted carry received by non-dom investment managers. But there are also obvious factors the other way, as some private equity managers will undoubtedly respond by leaving the UK (particularly non-doms, although they mostly aren’t in that £600m figure). Where managers leave there would be knock-on effects throughout the City and the wider economy, for good or for bad, which I am not competent to assess. Some would say these effects mean we shouldn’t change the way carried interest is taxed. Some would be sceptical about these effects. Others would say, as a matter of principle, everyone should pay tax on their employment income (which is realistically what it is) at the same rate. This article isn’t about these arguments.

The background to the deal

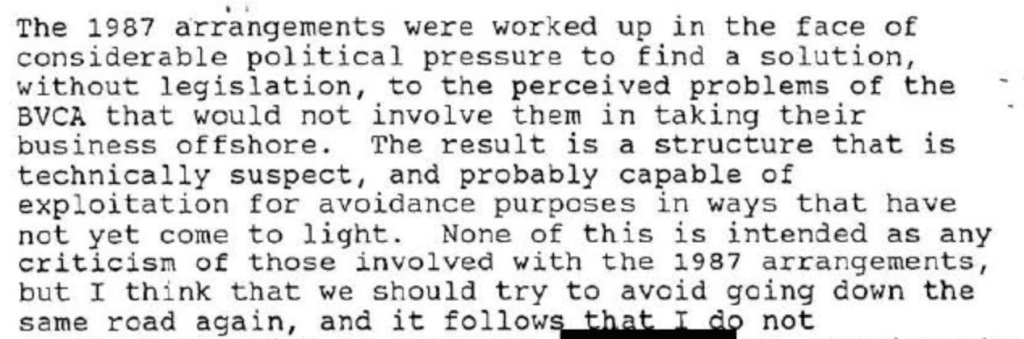

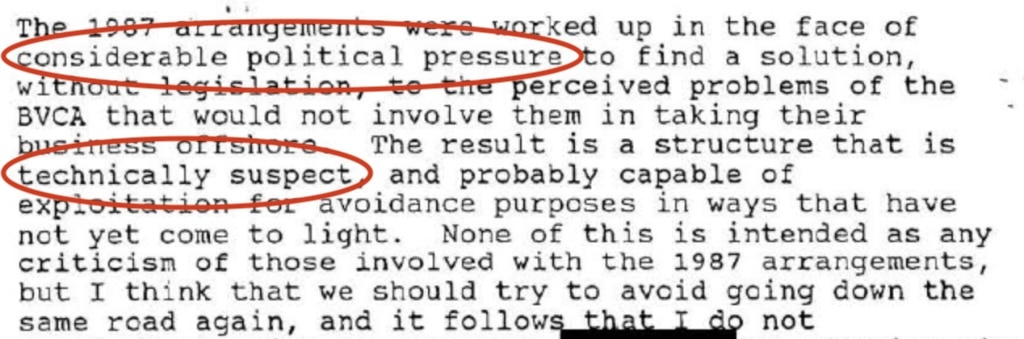

The FT published an illuminating history of the background to these discussions; you’ll see that it’s heavy on policy justifications, and light on technical tax justifications.4That continues to be the case. I think it’s fair to say that most of the pieces disagreeing with my original paper spent at least 25% of their time justifying the loophole on policy grounds; which is irrelevant to the point at issue. Now, thanks to documents disclosed by HMRC to the Good Law Project, we also know that senior HMRC personnel (writing two years later) believed it was created “in the face of considerable political pressure” and was “technically suspect”:5The prediction about the structure being “capable of exploitation” was very far-sighted. There have been multiple schemes, most egregiously the “base-cost shift”, which was common across the industry until 2015, and which enabled private equity fund managers to achieve an effective rate of tax on their carried interest in the single digits.

I wrote a paper, published by the British Tax Review earlier this year, saying that I too believed the 1987 deal was technically suspect.6Although I wasn’t aware of that memo at the time. I wrote a summary of the paper here.

The paper said that classic venture capital – acquiring a minority interest in a startup business – is unlikely to be trading. But the term “private equity” usually refers to “buyout funds”, which buy mature businesses, and later flip them at a profit. In my view, a typical buyout fund is likely trading. So I thought it was wrong, and very possibly unlawful, that HMRC permitted buyout funds to rely on the 1987 statement. It follows that managers of most buyout funds should pay tax at 47%.

The value of the deal

The beauty of the 1987 statement is that it reduces the capital gains vs trading question to just two boxes you can tick off: have the right structure and have the right intention. Compare with the HMRC guidance on trading, which goes on forever. Then tell me with a straight face that the 1987 statement is just a bland statement of the law.

In practice, everybody knows that paragraph 1.4 of the 1987 statement is a “cheat code” which enables private equity to skip the careful and cautious positions on trading taken by tax advisers on almost every other type of business.

When I was a practising lawyer, I would often be asked to issue opinions on whether an entity was trading.7Disclosure: I didn’t issue an opinions on this point to private equity firms, and this article and my other work in this area reveals no client-confidential information. At that point, I would suck my teeth in and say it was all very difficult, and the best I could do would be to say that I didn’t expect it to be trading, but it was a question of fact and HMRC might take a different view. My analysis would then proceed on the prudent basis that it either might be trading, or it might not be trading, and the client had to be happy with both outcomes.

This is how tax lawyers usually approach trading questions. What they never do is make deals or get clearances from HMRC: there are no sector-level deals apart from the 1987 BVCA statement, and in my experience HMRC would always refuse to give clearances on trading.

Private equity is completely different. There, the 1987 statement means that most8Certainly not all. advisers are supremely relaxed. In fact fund managers often don’t even ask for detailed specific advice on the point.

And that’s because of the BVCA statement.

Buyout funds therefore rely on the BVCA statement

That wasn’t the original intention. The 1987 statement the statement refers to “venture capital”, not private equity generally, or buyout funds. But at some point it started being extended.

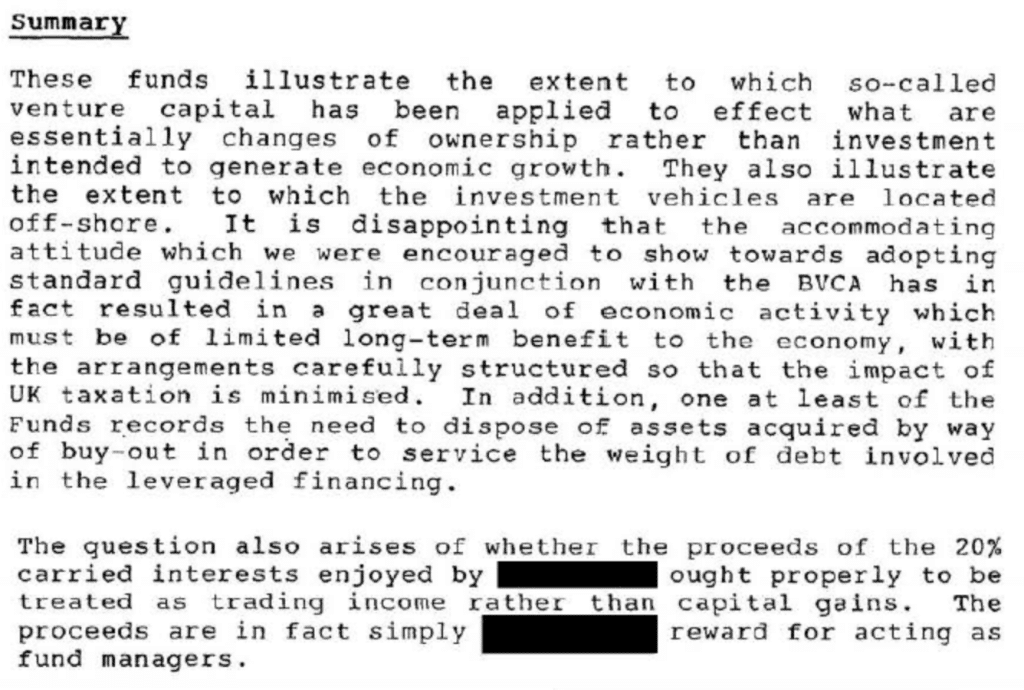

We now know, thanks thanks to another document disclosed by HMRC to the Good Law Project, that some people at HMRC saw this happening, and were unhappy. This is a 1989 memo from a tax inspector9Not the same person who wrote the memo excerpted above bemoaning the extension of the 1987 statement to buyout funds, and saying that this wasn’t the original intention:10Also far-sighted – look at the complaint about excessive leverage, well before it was fashionable.

But, whether that tax inspector liked it or not, it happened. The 1987 BVCA statement has, for the last 36 years, been used to extend the carried interest loophole to the whole private equity industry. They say this themselves:

Here’s how the BVCA’s website presents the document. Note “venture capital and private equity fund managers“:

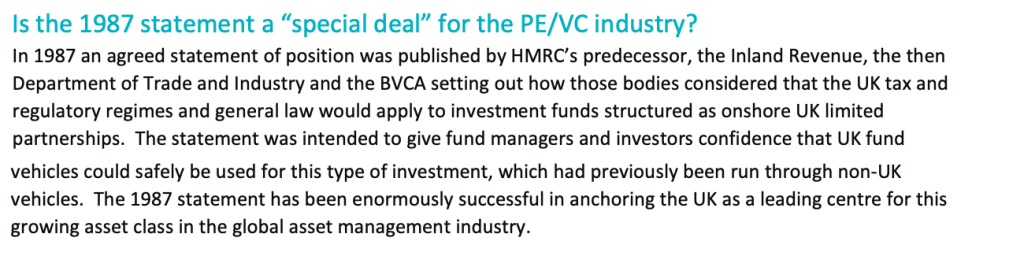

Here’s the BVCA’s response to my paper. Note “PE/VC“, and the reference to the industry as a whole:11We can also pause to raise our eyebrows at the two contradictory claims: it was just a statement of the law, not not a “special deal”. But it also gave the industry such confidence that it’s been an enormous success for the industry. Can’t be both.

That has now changed

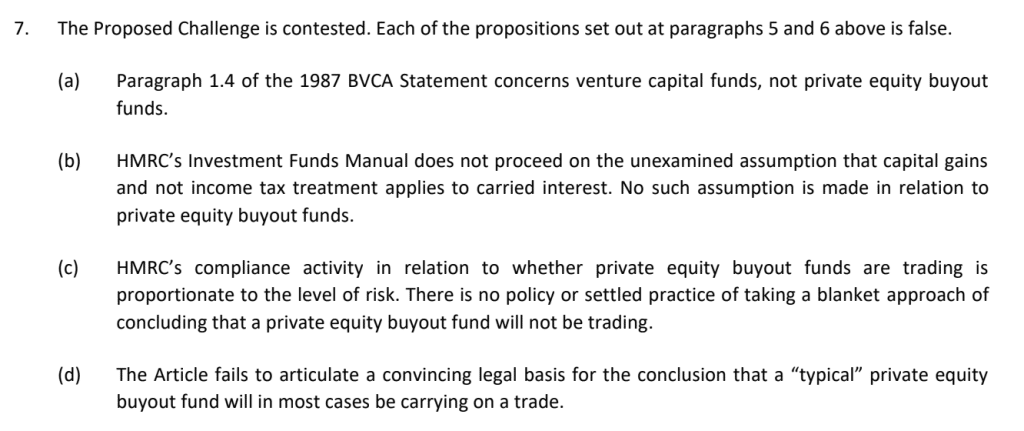

The Good Law Project recently commenced legal action against HMRC regarding the legality of the 1987 statement and its current policy. There’s lots to say about this, but here’s the key passage in HMRC’s response to the original Good Law Project letter:

Now HMRC contest everything, and that’s to be expected, but check out (a) and (b).

HMRC say the 1987 statement doesn’t apply to buyout funds. I spoke to a senior industry figure this morning and read this out to him, and he initially thought I was joking.

This gives the Good Law Project what they wanted, and so they don’t need to take the legal action any further.

And it puts private equity in a brave new world. Buyout fund tax advice can’t just rely on paragraph 1.4 of the 1987 BVCA statement. It has to consider the law. The fund managers will ask the advisers how confident they really are that they’re not trading (and if they don’t, investors12Investors because one of the silly consequences of the 1987 statement is that many investors’ own tax position will blow up if a manager does something that results in a fund trading will). And the advisers will have to say it’s not completely clear. HMRC is now able to open enquiries on individual funds – currently it seems they don’t have appetite to do this, but that could easily change within the 4-6 year lifetime of a fund. Any adviser who gives a clear opinion that a buyout fund isn’t trading is being commendably courageous.

That results in a level of uncertainty that managers may regard as unacceptable, and well-advised investors certainly will.

Some people will blame the Good Law Project, or even me, for this situation. They’d be right in that I don’t think lawsuits from campaigning groups are the answer. But we can’t have a tax system where one sector gets special favours thanks to a politically-driven “technically suspect” backroom deal 36 years ago. We should be taxed by law, not by lobbying or litigation.

It’s now in everyone’s interest for the taxation of carried interest to be put on a proper footing. Government should have the courage to take a position (one way or another) and Parliament should legislate.13And we should detach the tax consequence for the management team, whatever it may be, from the tax position of third party investors – their investment should never be on trading account for tax purposes.

-

1Or they pay a very small amount. Or they pay a larger amount, perhaps even as much as 5% of the total capital of the fund, but that is provided by a non-recourse loan which means they’re not actually out fo pocket. Either way, the executives are getting a deal that isn’t available to anyone else.

-

2Not really a loophole; because that and successive Governments have known and approved of it. However that’s the term often used, and so I’m afraid I will use it in this article. My apologies to purists.

-

3The source for the £600m figure is this FOIA, which shows £3.4bn of gains in the most recent tax year. The difference between CGT and income tax/NI on £3.4bn is £600m. This will be a significant under-estimate, because it doesn’t include the very substantial amount of unremitted carry received by non-dom investment managers. But there are also obvious factors the other way, as some private equity managers will undoubtedly respond by leaving the UK (particularly non-doms, although they mostly aren’t in that £600m figure). Where managers leave there would be knock-on effects throughout the City and the wider economy, for good or for bad, which I am not competent to assess. Some would say these effects mean we shouldn’t change the way carried interest is taxed. Some would be sceptical about these effects. Others would say, as a matter of principle, everyone should pay tax on their employment income (which is realistically what it is) at the same rate. This article isn’t about these arguments.

-

4That continues to be the case. I think it’s fair to say that most of the pieces disagreeing with my original paper spent at least 25% of their time justifying the loophole on policy grounds; which is irrelevant to the point at issue.

-

5The prediction about the structure being “capable of exploitation” was very far-sighted. There have been multiple schemes, most egregiously the “base-cost shift”, which was common across the industry until 2015, and which enabled private equity fund managers to achieve an effective rate of tax on their carried interest in the single digits.

-

6Although I wasn’t aware of that memo at the time.

-

7Disclosure: I didn’t issue an opinions on this point to private equity firms, and this article and my other work in this area reveals no client-confidential information.

-

8Certainly not all.

-

9Not the same person who wrote the memo excerpted above

-

10Also far-sighted – look at the complaint about excessive leverage, well before it was fashionable.

-

11We can also pause to raise our eyebrows at the two contradictory claims: it was just a statement of the law, not not a “special deal”. But it also gave the industry such confidence that it’s been an enormous success for the industry. Can’t be both.

-

12Investors because one of the silly consequences of the 1987 statement is that many investors’ own tax position will blow up if a manager does something that results in a fund trading

-

13And we should detach the tax consequence for the management team, whatever it may be, from the tax position of third party investors – their investment should never be on trading account for tax purposes.

10 responses to “Did the Good Law Project just kill carried interest?”

Notwithstanding HMRC’s comment at 7(b), and repeated subsequently, that “no such assumption is made in relation to private equity funds”, HMRC’s response then goes on to forcefully rebut the starting position that buyout funds are so trading. While comments such as “the typical buyout fund is unlikely to be trading” opened the door to doubt, in practice this doubt must be vanishingly small given HMRC states it has no plans to frequently investigate whether particular funds may not be so typical, and neither major political party seems to have any ambition to apply pressure otherwise. So as it stands, I’m not sure I would be particularly concerned if I was an individual fortunate enough to have a carry entitlement. As an aside… I wish HMRC would so vigorously defend my own rights to pay concessional rates of tax.

The problem, and it is a problem, could be substantially addressed, along with many other Capital / Revenue issues, simply by equalising rates of taxation for Capital Gains with those or income.

Yes and no. Agreed, it is a problem and adds to the issue of perceived unfairness by the general population. I’d argue however that equalising income and CGT is reasonable only with the proviso that there is indexation, to account for the time value of money.

The unfairness is not merely “perceived” but actual.

You may have a point with regard to indexation but as long as we tax interest on deposits paid at below the rate of inflation then there is no reason why we should not also tax the inflationary part of gains. Consistency would require that gains are fully taxed.

Correct, thanks John, I realised after my post that I should have said actual not perceived unfairness (remember the “I pay less tax than my cleaner” outcry).

You also have a point about interest (apart from the personal savings allowance) but I can’t get my head around someone being taxed the same on a gain made over several decades holding an asset versus flipping something over a few hours or days. I suppose tapering relief was an attempt to make a proxy for indexation without the need for lots of valuation arguments. Tricky one.

From 1982, Capital Gains (net of inflation) *were* taxed as a top slice of income.

I seem to remember something about gains prior to 1965 not being taxable.

In 1988, all assets were rebased to their values as of 1982/03/31. (was it 1982/04/05 for individuals?)

So for the first 10 years after the statement, how much difference did the statement make?

Was it just that no NI (employer or employee) was payable? In practice about 9.5% (10.45/110.45).

The big gap opened up in 1997 when Gordon Brown got rid of indexation from 1998/04/05 and cut the CGT rate “to compensate”.

Currently the gap is (47+13.8/113.8) – 28 = 25.4%, but without indexation for inflation.

From 1998-2008 taper relief meant that it was between than 25.4% and 35%.

Could HMRC argue that thier view stated in para 7 of their letter to Good Law Project ( quoted above) has ALWAYS been the case? This position may then allow HMRC to open up enquiries into tax returns of fund managers, who declared carried interest on buy-out deals as capital gains, for up to 20 previous years?

This could turn into a ‘loan charge’ type scandal for well-healed private equity executives. With a change of Government I could see this happening.

I have to say I’d be on the fund manager’s side there. Whatever HMRC says now, I think fund managers had a legitimate expectation that carried interest was taxed as a capital gain provided the narrow conditions in the 1987 statement were satisfied.

There’s a difference between what the fund manager does (trading) and what the fund does (possibly trading, possibly not). The IME requires that distinction if the fund is trading.

The DIMF and income based carried interest rules cover most of the worse abuses. If the fund is having to hold investments with a lifespan of over 3 years before you get capital treatment, the probability is that its capital, not income. Housebuilders, retailers, other ‘trading’ businesses dont intend to hold stock for 3 years.

This is a ‘whatevs’ from HMRC

Dan,

Clearly an area where there are different interpretations and not a universal agreement. Other commentators (eg Simmons & Simmons) have expressed a different interpretation, so there is professional disagreement about the material in the public domain.

Personally, in any case or dispute I would be very reluctant to place any substance on a few words by an anonymous tax official. So not convinced of the claim of political pressure or technically suspect. Incidentally, I am assuming that arguments over whether or not trading has occured is primarily a factual question, to which the legal badges can then be applied. I think it entirely possible that the issue came to attention (like other issues) and there was a view that it needed to be resolved and a central position adopted. I don’t see that as political pressure. That’s not really any different from other areas (eg Discovery after Veltema). As Stephen Daly has written, there is a discretion over legal interpretation – what else are statements of practice?

People may have misunderstood or misapplied the principles but I don’t see this as the Inland Revenue consciously and persistently acting in contravention of the law.

Whether the memo was well drafted, or created ambiguity, is a different question. I suspect that it would now not be written in the same way, or perhaps not even written at all given subsequent judicial steers on tbe scope of HMRC’s discretion. Wonder if Stephen Daly has read any of the current material and has a view?