UPDATE: this was written on 19 January, and I haven’t updated it. We subsequently learned (thanks to the Guardian) that Zahawi had been charged a large penalty. And we now know, thanks to Sir Laurie Magnus, that HMRC started investigating Zahawi well before the start of this timeline, and that Zahawi knew about that by April 2021. This timeline therefore is too kind to Zahawi: his deceptions were more serious than I knew on 19 January. It is also not kind enough to HMRC; it seems likely that, but the time I started analysing the Balshore structure, HMRC were already onto it.

There’s a very lengthy backstory to Nadhim Zahawi’s HMRC settlement, and lots of people have been asking me to summarise it. Here goes:

23 June 2022: I fired a Freedom of Information Act request at HMRC to establish if any Ministers are under HMRC enquiry. I was initially told at at least one was; HMRC now tell me none are. (This is important later.) Mentioned in the later FT story here.1For completeness, the story doesn’t mention me because I asked Jim Pickard to keep my name out of it, and he kindly obliged – it felt too political for where I wanted Tax Policy Associates to be. The original FOIA application was mine, but Jim worked with me on interpreting it and responding to it, and deserves credit for the story that started the path that led to my Zahawi findings.

5 July 2022: Nadhim Zahawi becomes Chancellor of the Exchequer

6 July 2022: The Independent reports that Zahawi had been the subject of an investigation by the NCA, the SFO and HMRC. Zahawi denied this – but how would he know if he was being investigated? Then the Guardian reports that the Cabinet Office had raised a “red flag” about Zahawi’s tax affairs before his appointment as Chancellor. This was pointedly not denied by the Cabinet Office. That caught my interest. I pulled all the publicly available documents on Zahawi’s business activities and started looking through them.

7 July 2022: I spot a filing error in the accounts of an unrelated company, Crowd2Fund Limited, which proves that Balshore Investments Limited, a Gibraltar company previously linked to Zahawi, is held by a trust controlled by Zahawi’s parents.

9 July 2022: I conclude that, when Zahawi established YouGov in 2000, he arranged for the founder shares that would have been his to go to Balshore. It paid nothing for the shares. The only plausible reason for this is tax avoidance. I check my conclusions carefully and speak to tax accountants, solicitors, QCs and retired HMRC inspectors, as well as entrepreneurs familiar with startup formation. I’m stunned by the unanimity of opinion: this stinks.

10 July 2022: I publish. I’ve calculated the tax I think Zahawi avoided – it’s mostly the gain on the YouGov shares which would have been subject to CGT had Zahawi held them, but is tax free in Gibraltar. The figure is £3.7m (a lower bound; I make some conservative assumptions).

11 July 2022: Zahawi is interviewed by Kay Burley. He says: “There have been claims I benefit from an offshore trust. Again let me be clear, I do not benefit from an offshore trust. Nor does my wife. We don’t benefit at all from that.”

13 July 2022: Zahawi’s people have been claiming Balshore got the shares because his father provided startup capital. I go through all the documents and accounts again, and am satisfied this is false. I say so, and challenge Zahawi to correct me if I’ve gotten it wrong. I know his people see this.

14 July 2022: Zahawi’s people respond by seamlessly jumping to a new explanation: that Balshore got the YouGov shares because Zahawi “had no experience of running a business at the time and so relied heavily on the support and guidance of his father, who was an experienced entrepreneur”. There is nothing in any documentation I could find, or in the publically known history of YouGov, to support this story.

16 July 2022, 8am: An investigation by The Times suggests the new explanation is false – YouGov itself, and people present at its founding, say his father wasn’t involved in the business. Zahawi is able to rustle up two people who say they met his father and he was helpful. I’m pretty helpful – nobody hands me a 40% shareholding in their startup.

16 July 2022, 8.40am: I conclude this all means Zahawi’s first explanation, that his father provided startup capital, was a lie. It is provably false, and the ease with which he slipped to a new explanation suggests it was deliberately false. I tweet this.

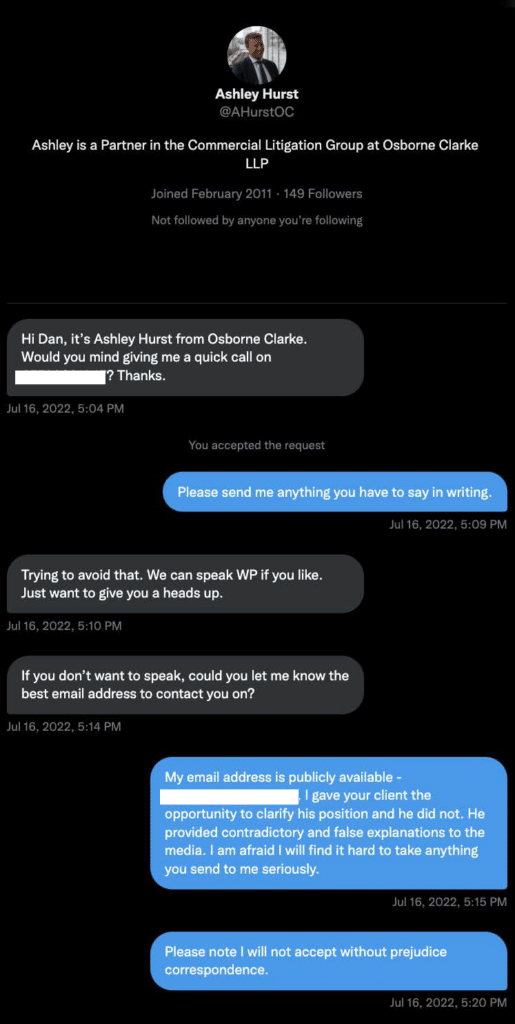

16 July 2022, 5pm: I receive a Twitter direct message from Osborne Clarke, Zahawi’s libel lawyers, asking to speak. I tell him to put anything he has to say in writing, and that I won’t accept “without prejudice” correspondence (which is normally kept private):

16 July 2022, 7pm: I receive an email from Osborne Clarke, labelled “without prejudice”. It tells me I cannot publish or even refer to it, and that would be a “serious matter”. It requires me to retract my allegation of lies by the end of the day, or they will write to me on an “open basis” (which usually means: they will send a “letter before action” threatening to sue me). The email is a confused mess, accusing me of saying Zahawi’s second explanation was a lie, when in fact I said his first explanation was a lie. Seems like pure bluster. No need to react.

17 July 2022: I do some more analysis. A chance company law error means YouGov IPO documents disclosed that a £99,000 dividend from Balshore was redirected to Zahawi. His claim to not have benefited from the trust is false. The obvious inference is that there were many gifts; it’s just happenstance we see this one. A forensic accountant working with me identifies almost £30m of unsecured loans going into Zahawi’s property company. Another obvious inference: some of this may be the YouGov profits coming back to Zahawi.

19 July 2022, 8am: I receive a letter from Osborne Clarke. This time it addresses what I actually said, but tells two fibs. First, it says that Balshore paid £7,000 for the shares in 2000. I’m reasonably confident it didn’t – two years later a back-dated Companies House form was filed and £7,000 paid (see page 4 here; the accounts are consistent with that). Second, it claims that £7,000 was “startup capital” – just daft. Why is he saying things that clearly aren’t true? Why are his lawyers repeating them? Again I’m warned I can’t publish the letter.

19 July 2022, 9am: I realise what the letter doesn’t contain: a statement that Zahawi’s taxes have been fully reported and paid to HMRC. I publish my analysis from the 17th.

20 July 2022: I keep hearing that other people are receiving threatening letters from Osborne Clarke, containing warnings not to publish. Time to think about whether these warnings are true. I’m not an expert in confidentiality law, but I know enough to get by, and their claim feels like nonsense. And it’s outrageous that Zahawi thinks he can not only use libel law to shut people up, and do it in secret. I call a contact who is a leading expert in confidentiality law, and he snorts with derision down the line. I call a few more, just to be cautious – lots of snorting.

22 July 2022: I publish the Osborne Clarke letters, and explain why legally I am entitled to. The Times reports it. This goes slightly viral. The Tax Policy Associates website normally gets a few thousand readers a day – today we got 400,000. Turns out people don’t like the Chancellor of the Exchequer secretly stopping people writing about his tax avoidance.

25 July 2022: I write to the Solicitors Regulation Authority, asking them to end the practice of libel lawyers sending threatening letters which they falsely claim can’t be published (or even mentioned).

1 August 2022. At this point I’ve reached an impasse. I think I’ve proven that Zahawi has lied about the YouGov structure – that and everything else makes me reasonably certain that he has avoided around £3.7m in tax. But there’s been little media interest. Why? Partly Zahawi firing out libel threats. But I think mostly that we’ve been overwhelmed by politics, and scandal, and this just didn’t break through. All I can do is keep plugging away.

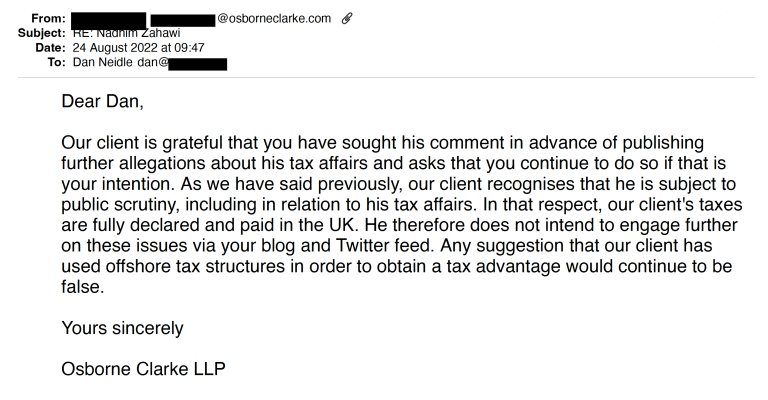

24 August 2022. I ask Zahawi, through his lawyers, why there are so many inconsistencies in his story. And specifically, why he told Kay Burley he doesn’t benefit from the trust, when we know he received £99,000 from it. They duck the question. But they tell me Zahawi’s taxes are “fully declared and paid in the UK”.

6 September 2022: Zahawi steps down as Chancellor.

We now know that, at about this time, his accountants probably approached HMRC to settle his unpaid YouGov taxes – likely the same taxes I said he’d tried to avoid. Why now? Because settlements take time. If everything was finalised in early January, then he must have approached HMRC in early Autumn. And for several weeks before that (at least) his accountants must have been preparing their approach.

So we can’t be sure exactly when – but it’s likely that at some point around this date, Zahawi knew that his tax was not fully declared and paid, and that what I’d written in July was in substance correct.

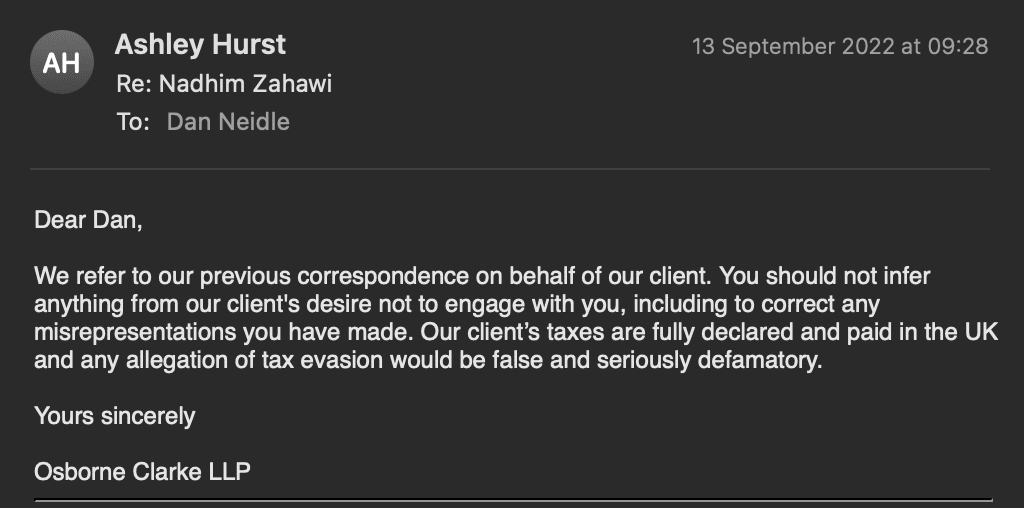

13 September 2022. More evasion from Osborne Clarke. But one clear statement: “Our client’s taxes are fully declared and paid in the UK”.

15 October 2022. A second libel threat from a second set of lawyers acting for Zahawi. I posted an innocuous tweet referring to the Independent report that Zahawi had been investigated by the NCA and HMRC. The threat looks like an automated mailshot – it doesn’t refer to my previous correspondence with Zahawi, and doesn’t seem to realise I am a tax lawyer. It’s amateur hour.

29 November 2022. A great response from the SRA. They issue a warning for solicitors to stop sending libel letters which falsely claim to be confidential, and say they can’t be published. It’s not a change in practice, it’s a statement of what has always been the case – lawyers can’t lie.

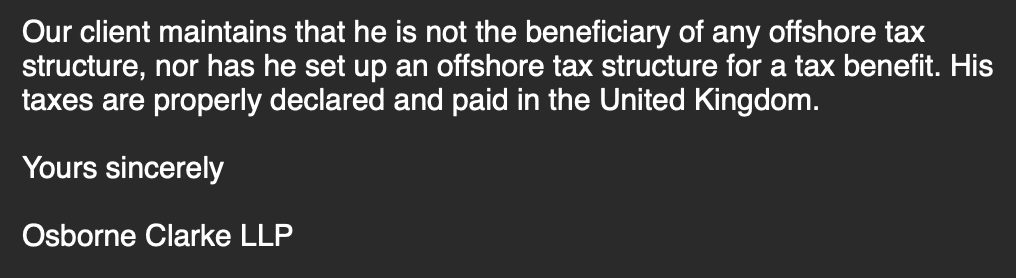

1 December 2022: yet another evasive non-response from Osborne Clarke to my questions. But again one clear statement: “[Zahawi’s] taxes are properly declared and paid in the United Kingdom”:

(At this point it seems highly likely that Zahawi was deep into settlement discussions with HMRC, and therefore he knew that this statement was false)

2 December 2022. Given the clear statement from the SRA, I refer Zahawi’s lawyers, Osborne Clarke, to the SRA. Lying and bullying should have consequences.

3 December 2022: At this point the Zahawi story looks dead. His strategy of saying nothing seems to have won out.

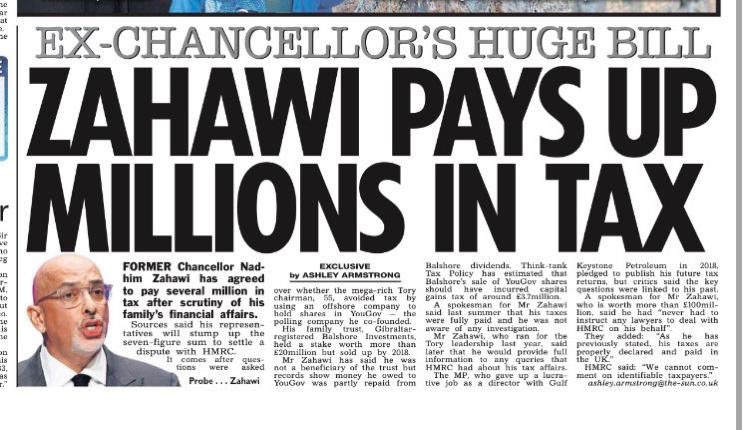

15 January 2023. Everything changes. An absolute scoop from Ashley Armstrong in The Sun on Sunday. Zahawi paid millions in tax to settle a dispute. There’s a hilarious non-denial denial from Zahawi that he “never had to instruct any lawyers to deal with HMRC on his behalf”. Later that day, that line is dropped – he doesn’t deny the story, he just refuses to comment.

The obvious conclusion: Zahawi responded to my July analysis by instructing accountants to seek a “contractual settlement” with HMRC before an enquiry could be raised. This isn’t a dispute in the usual sense (“taxpayer says X, HMRC says Y”). It’s an admission that tax that was due wasn’t paid. These settlements are confidential. Zahawi was trying to make it all go away, quickly and quietly.

16 January 2023. There is now a flurry of press interest. The Times. The FT. BBC online. LBC. Five Live (starts at 2:41:07). Radio 4 pm (starts at 46:44). The Independent. Sky News. More.

Zahawi puts out a statement: his taxes are “properly declared and paid in the UK”. This can only be true in the most hyper-literal sense: today, his taxes (maybe) are properly declared in the UK. When he approached HMRC for a settlement, they certainly weren’t.

18 January 2023, 12pm: Rishi Sunak is asked about Zahawi’s settlement at Prime Minister’s questions. I’ve the highest regard for Sunak’s probity. I know people who worked with him – they’ve no doubt as to his intelligence and his honesty. So it’s disappointing to hear this. No, Zahawi has not “addressed this matter in full”.

18 January 2023. 10:30pm: Zahawi provides a clear statement to Newsnight (report starts at 13:25) that his tax affairs “were and are fully up to date”. No more games with tenses.

If/when the settlement details come out, we will know for sure this was a lie. And we’ll know that all the denials his lawyers issued to me were a lie – because at the very time they were made, Zahawi was negotiating a settlement to quietly cover up the fact he’d avoided millions in tax.

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – just so people can clearly see the more technical comments. I will also delete comments which are political in nature.

-

1For completeness, the story doesn’t mention me because I asked Jim Pickard to keep my name out of it, and he kindly obliged – it felt too political for where I wanted Tax Policy Associates to be. The original FOIA application was mine, but Jim worked with me on interpreting it and responding to it, and deserves credit for the story that started the path that led to my Zahawi findings.

31 responses to “Nadhim Zahawi – the whole story”

This is really great work , well done . What is it with chancellors and tax avoidance ? I would highly recommend a look at Phillip Hammonds trust arrangements.

Hi Dan,

I could be wrong, but isn’t it the case that if a mistake is made under one HMRC tax regime and the regime has changed by the time the penalty is imposed, the current or more punitive of the two regimes is applied as an additional condition of failing to properly declare one’s taxes?

So in March 2020 the 10% lifetime Entrepreneurs relief on the first £10m was cut right down to £1m.

Given Zahawi sold his company before this CGT change, and was so carelessly greedy that he even tried to avoid that. How is it that he is still being allowed to enjoy all the preferential pre-rule change and yet his conduct has been deemed sufficiently purposeful to collect a penalty?

In other words should the fine and taxes reflect that there was only a 10% on the first £1m by the time he settled up and so he’s liable for a full CGT rate and not 10% on the other £9m?

Has HMRC been lenient and might that have anything to do that he was the chancellor at the time he negotiated his way out of this mess!

The annoying answer is “it depends on the precise transitional provisions”. As to how it ends up at 3.7m, I’m not sure. The coincidence of aligning with my original estimate is a little surprising, given that he presumably didn’t actually claim entrepreneur’s relief. So it may well be that I’m right on the big 2017/18 gain, the earlier 2005/6 gain was out of time, and there’s some additional gain or dividends I’ve missed. We may never know!

Thanks Dan. The reduction in the £10m Entrepreneurs relief to £1m was driven by an increasing fear that small group had been gaming this privilege. Using companies in spouses or dependents names to somehow reduce their taxes on amounts many times greater than even the £10m! Unfortunately rather than go after this lot, they changed the rule for all.

But returning to your point, its outrageous that a cabinet level position, even more so one were the title was head of the very ministry investigating them wasn’t required to be completely transparent. The transgression/penalty alone should be enough reason for post-event sunlight to be shone on Zahawi’s affairs.

Mention has been made of ER. But this needs to be claimed and looking at the dates he would have been time barred.

thanks – yes, that’s a great point.

There is never a justiiification ofr setting up – at some considerable expense (both initial and on-going) – any offshore structure unless it is for avoidance or evasion.

For a Uk domiciled individual, in this case, I agree. More widely, there absolutely are legitimate uses for offshore, which I should write about sometime!

Dan, this is an excellent forensic piece of work – but I am curious to know more. Do you know what the actual cash gain was for Balshore? It looks from the tax NZ has paid that he might have been allowed to claim Entrepreneurs’ relief (CGT @ 10%) when the tax charge was eventually calculated. But the gain was made by Balshore, which wouldn’t have been entitled to that relief if it had been a UK entity liable to CGT. So if NZ chose NOT to make his gain onshore, would he be able to calculate his tax at the same super-low rate as those who stayed within the UK tax system all along?

of course you’re right – when I talk in that article about the tax avoided, I’m calculating the tax that would have been paid had the shares been in Zahawi’s hands. How the tax computation actually works depends on the precise basis on which Zahawi was taxed. Here I suspect HMRC had a long menu of options, and at this point it’s premature to speculate which road they went down. The coincidence of numbers suggests it was very like the calculation I made (and not, e.g., application of ERS rules, which could have resulted in a whole lot more tax at the marginal income tax rate).

In due course, when the facts are clear, I look forward to an article in The Tax Journal on the seventeen possible tax outcomes here!

Sorry, a second long comment today. But I did wonder if we could try to understand what actually happened in 2017-2018, toto try to get a little more specific about the calculation of the capital gains and the tax due.

You gave an estimate of about £3.7m of tax potentially unpaid last July.

Ignoring transactions in 2006 and 2008, and focusing on the 2017-2018 transactions, is it as simple as Balshore Investments holding about 8 million shares (7.6% of the capital) in the 31 July 2017 annual accounts of YouGov plc, when they were worth about 250 pence each, and no shares (less than 3%, so less than around 3.1 million) in the 2018 accounts?

So, on the assumption that Balshore sold all 8 million shares at 250 pence, with little or no base cost or other deductions or reliefs, the proceeds of £20 million becomes a taxable gain of about the same amount.

If entrepreneurs’ relief applied then the first £10 million of gain would be taxed at 10%, and the next £10 million at 20% That would be £3 million of tax. But query if ER did apply. For example, was Zahawi an officer or employee? If not, the tax could be £4 million. And based on the public information mentioned below, the assumed price of 250 pence look like a lower bound.

Zahawi could put some more facts into the public domain to be more transparent – the legal and factual basis for the recent settlement must be spelled out somewhere, including the timing of the transactions, the disposal proceeds, and the calculation of the gain and the penalty. It is not at all clear to me why we should have to wait for the conclusions of an ethics adviser when the facts must have been agreed with HMRC.

In the absence of clear facts openly acknowledged, we can interrogate the available public sources of information to supplement the outline analysis above and draw some reasonable inferences. Perhaps this is a fools errand without clear facts, but here goes.

YouGov has been AIM listed since 2005 so its share price is a matter of public record. It ranged from about 250 pence in July 2017 up towards 500 pence 12 months later. (The share price is currently about £10, but reached £16 last year, so Balshore might have done better to hold on to the shares, but perhaps the net proceeds have been invested wisely…)

We don’t know exactly in 2017-2018 when these shares were sold – I suspect not in one lot, nor in a series of small packets spread over the whole year, but probably as a private deal to offload shares to one or more other large shareholders in a few relatively large chunks, as it is no simple matter to sell nearly 8% of a listed company – but the daily trade volumes are also a matter of public record. The volume of YouGov shares traded on a typical day in that period is under 100,000. In that year, there are only five days when the volume was over 1 million – three days in September 2017 when just over 1 million shares were traded each day and the quoted price was around 250 pence, and two days when over four million shares were traded, 23 October 2017 and 9 February 2018, when the quoted price was around 315 pence.

That said, if this was an off-market private deal, the sale price may be a somewhat below the quoted price on the market. Perhaps it was £2.50, but around £3 might be right. That could push the gain up to £24 million. With ER on the first £10m, that might be tax of about £3.8 million (similar to your initial estimate). At a flat 20% it would be £4.8 million. So are we sure the penalty was 30%?

YouGov’s Regulatory News Service announcements are also a matter of public record. (As I understand it, a shareholder in a listed company must disclose and the company must publish when the shareholder crosses a 3% threshold, and every whole percentage of shares above that, but there is no mandatory reporting when a shareholder drops below a reporting level.) As a matter of fact, shortly after both of the two days when over 4 million shares were traded, one major shareholder reported that its shareholding increased substantially. From July 2017 to July 2018, that shareholder’s holding increased by about 8.2 million shares. This could be a coincidence: the holdings of a few other major shareholders increased by a few million shares, and a few fell by similar amounts, over that year. Together, the major (3%+) shareholders account for about 79% of the capital in the July 2017 accounts, and about 80% in July 2018, so it seems unlikely that many of the shares were bought from or sold to “the public”.

It would be an easy matter to put a clear statement of facts on the record, so I can’t help being a little suspicious that the facts remain so unclear. Perhaps there is more to find out here?

Hi Andrew, you are absolutely right – there is so much we don’t know, and the safe assumption is that this isn’t because things are better/cleaner than they appear.

We don’t know how the money found its way back to Zahawi (although I expect it did). We don’t know the total gain, or total dividends received. My calculation was a fairly conservative estimate that excluded dividends altogether. I deliberately haven’t set out how I think the transaction was taxed, because there are too many unknowns (and indeed too many options for HMRC).

The one feature throughout has been that, of the thousands of qualified tax accountants/lawyers in the UK, nobody has said “yeah, this is completely fine and normal!”

Along with many others very grateful and full of admiration for your persistence on this matter.

There must have been an occasion, a moment when Z went from not knowing/realising that he owed tax, to knowing/realising that he did. Was it a damascene moment, or a creeping realisation? Presumably the events went something like this (with dates and certain facts to be established, so this may not be in correct chronological order):

Date Event To be established Z’s position

?? Shares in You Gov are sold, for a sum that was c. £20m greater than acquisition cost. Who was the selling party?

Whose bank account received the proceeds? Z does not consider that taxable gain has accrued to him.

?? Z completes UK tax Return for the year in which sale was made. No taxable gain to be reported.

?? Z realises or concludes taxable gain has accrued to him What triggers this? Loss of carelessness? Some CGT payable. When was this due?

?? Z informs HMRC that he omitted to declare a taxable gain that has accrued to him How does he explain the original omission?

?? HMRC calculates tax payable on gain and determines penalty and interest payable. Agreed after negotiation with Z and his advisers, or was HMRC calculation accepted by Z?

?? Z pays amounts due to HMRC Tax affairs are in order

?? Z informs PM that his tax affairs are in order

Which are the action(s) or decision(s) of Z that in his opnion constitute ‘carelessness’?

In addition, of uncertainty in terms of sequence are:

1 At what stage does Z consider/realise that his tax affairs are not in order? Presumably at all times up to this time he did consider them to be in order.

2 At what stage after that does he consider them to be in order once again? On agreement with HMRC of the amount due and the fine payable [date?], or on payment of these amounts [date?]?

3 When do the incidents involving/reported by Dan E occur in the timetable above, in particular:

16 July 2022: Osborne Clarke send email to DE, labelled “without prejudice”.

?? ????: Z’s accountants approach HMRC to settle any unpaid YouGov taxes

15 October 2022. Second libel threat from a second set of lawyers acting for Zahawi.

I have just posted a comment on the FT website about all this. I am concerned that insufficient attention is being paid to the reasons why Zahawi put the founder shares in the family trust in Gibraltar in the first place if it was not to avoid tax. And who received the realised capital gain? Do we know that? Is it possible to find out.

I cannot believe that when Zahawi set up YouGov with Shakespeare that he did not hope/expect that he would gain financially from the enterprise.

Great work here – I’m particularly enjoying the hilarious “Careless” defence.

Carelessness is seldom associated with tax planning and Gibraltar-based trusts!

Mr Zahawi says HMRC accept that he was merely careless.

It is reported that a penalty of 30% makes up part of the settlement.

I understand that 30%is the maximum percentage for careless conduct. So, I’m puzzled why he apparently got no discount for cooperating with HMRC in their enquiry, assuming that he did cooperate.

It seems to be a case of failing to disclosure a capital gain made on the sale of shares in a UK company that he was the beneficial owner of., ie the gain was not of an overseas asset.

Careless penalties can be suspended. It would be interesting to know if suspension was sought and, if sought, refused.

Typo? I think you filed the FOI request rather than fired it with either rifle or fuel !

my wife said the same! I always think I’m firing them at HMRC, but that could just be my over-dramatic sensibilities…

I’m not convinced that there wasn’t an enquiry/investigation. The FT article refers to HMRC admitting a mistake when they said no ministers were under enquiry and correcting their statement to say that one was.

The “never had to instruct any lawyers to deal with HMRC on his behalf” leaves open the possibility that his accountants were dealing with HMRC (possibly with legal support in the background).

Most importantly, though, the reports that he paid a 30% penalty in relation to “careless” behaviour, if true, strongly suggest that this wasn’t a disclosure case. 30% is the maximum of the carelessness range and it’s fairly unusual to land here. Disclosure, the quality of disclosure, and the assistance the taxpayer gives in getting to the right answer, will typically reduce it.

If he’s receiving no credit for “telling” and “helping” then, even if a disclosure was made, it was obviously so poor that HMRC would almost certainly have opened an investigation to get to the bottom of it.

One other, rather pedantic, possibility could be around the difference between a Self-assessment “Enquiry” and the investigation that would follow HMRC making a discovery assessment, which strictly isn’t under the legal framework referred to as an Enquiry .

Second Patrick’s comment above – ditto the clarity of your blog. Active citizens read and learn. Thank you, Dan – and a much belated but HNY2023 🕊

This Active citizen Is reading and learning…and is “gob smacked” .

Brilliant work.

Great work Dan. The people who have influence, power and wealth deprive us all of a civilised society by not paying their tax. Brooks in his work The Great Tax Robbery, in 2013 states direct and indirect taxation fraud achieves 55 prosecutions per £1bn of fraud compared to 9100 prosecutions for benefit fraud. It’s clear where all the effort is directed. In these difficult times the government pleads poverty continuously for the last 12 years to pay public services but tax avoidance and fraud is alleged to be up to £32bn. Even with all the forensic work from Dan, Zahawi will never face a court and is in the enviable position of his ilk of negotiating how much they pay in tax, and when. Wish that we could all have that privilege!

Brilliant investigative work Dan. Maybe the time has come for all Government Ministers to have to declare their tax affairs on a public register together with any commercial interests.

It’s definitely worth discussing. My feeling is not. It invades the privacy of people who probably have done nothing wrong. It wouldn’t catch people who “forget” to declare income/assets. And the fun stuff often isn’t in the personal tax return anyway

>And the fun stuff often isn’t in the personal tax return anyway.

Where does the “fun stuff” usually lie Dan? What’s the most common form of tax avoidance for these horrible people?

Do something in a company/trust. Reach a position that it doesn’t impact your own tax return. Ta-da! And that is absolutely what Zahawi did – his tax return would have revealed nothing!

Well done indeed! A triumph for expertise, courage, determination and the FOI. Does payment of a penalty, said today to be 30% of the unpaid CGT, preclude prosecution for tax evasion?

A contractual settlement generally precludes prosecution. The taxpayer promises they’ve given full and complete disclosure to HMRC and pays the tax (and penalties). If it later turns out that the taxpayer wasn’t complete in their disclosure, prosecution can follow…

Surely the 99k dividend (your 17 July entry) would have to be on his tax return? Either way brilliant work.

It certainly should have been! I asked him repeatedly if it was, and he refused to answer. The suspicion is that it wasn’t, because if you knew what you were doing, you wouldn’t have a structure like this. I think it’s now reasonable to say that it probably wasn’t reported to HMRC.