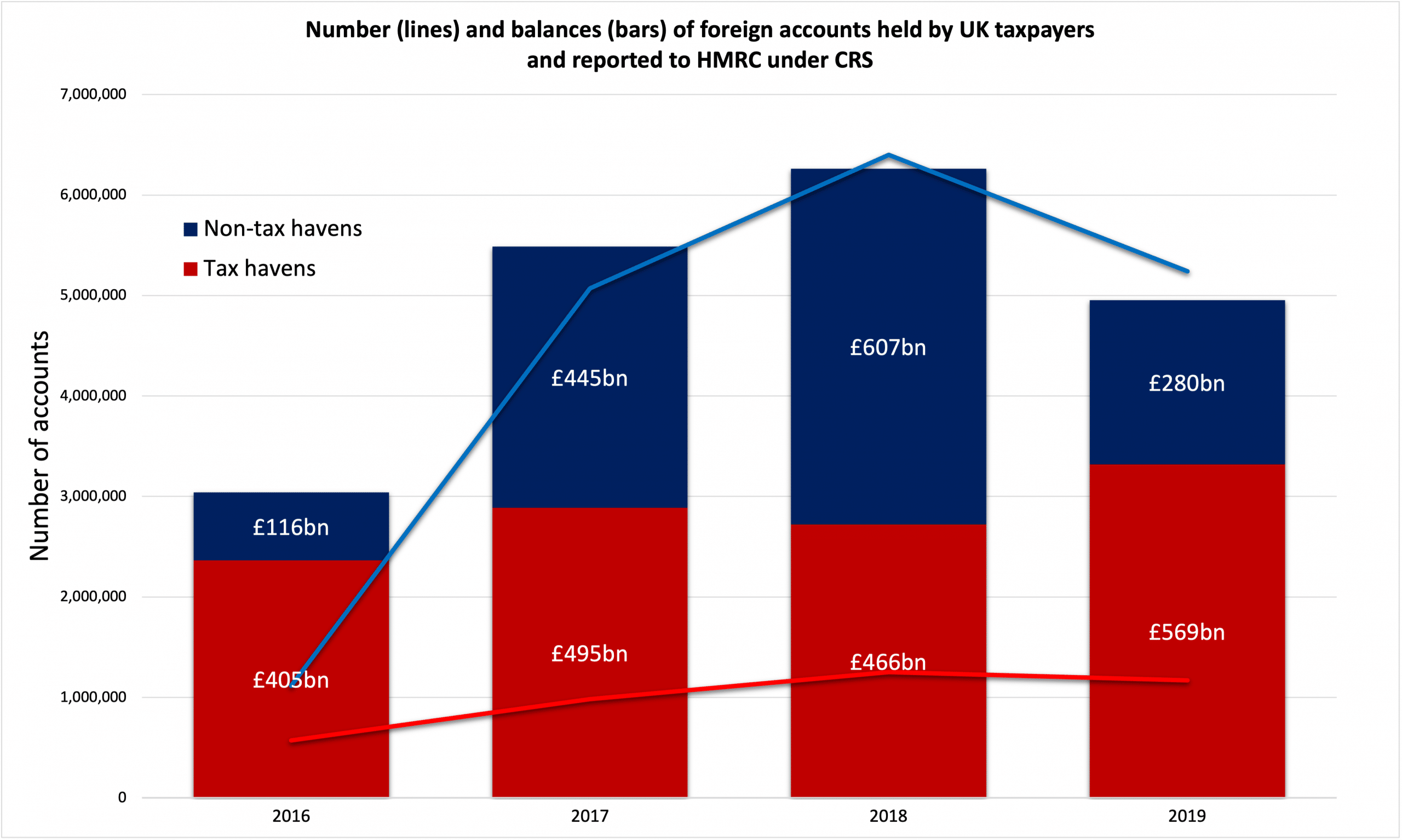

FOIA requests made by Tax Policy Associates reveal that £570bn is held in tax haven bank accounts by UK taxpayers, but HMRC has made no attempt to estimate how much of this is undeclared in UK tax returns, and therefore reflects tax lost to criminal tax evasion.

The background

Since 2018, almost all UK residents with overseas bank accounts have had their name, tax ID, and the balance and income on those accounts automatically reported to HMRC every year. That’s part of a revolutionary global project – the OECD Automatic Exchange of Information/Common Reporting Standard (CRS), under which €10 trillion of accounts were reported worldwide in 2019.

This should be a bonanza for HMRC. We’re all (except non-doms) supposed to declare income from foreign accounts in our tax returns, with up to 300% penalties if we don’t. So if someone has foreign account income reported under CRS which wasn’t included in their tax return, and they’re not a non-dom, HMRC should be able to immediately identify potential tax evasion.

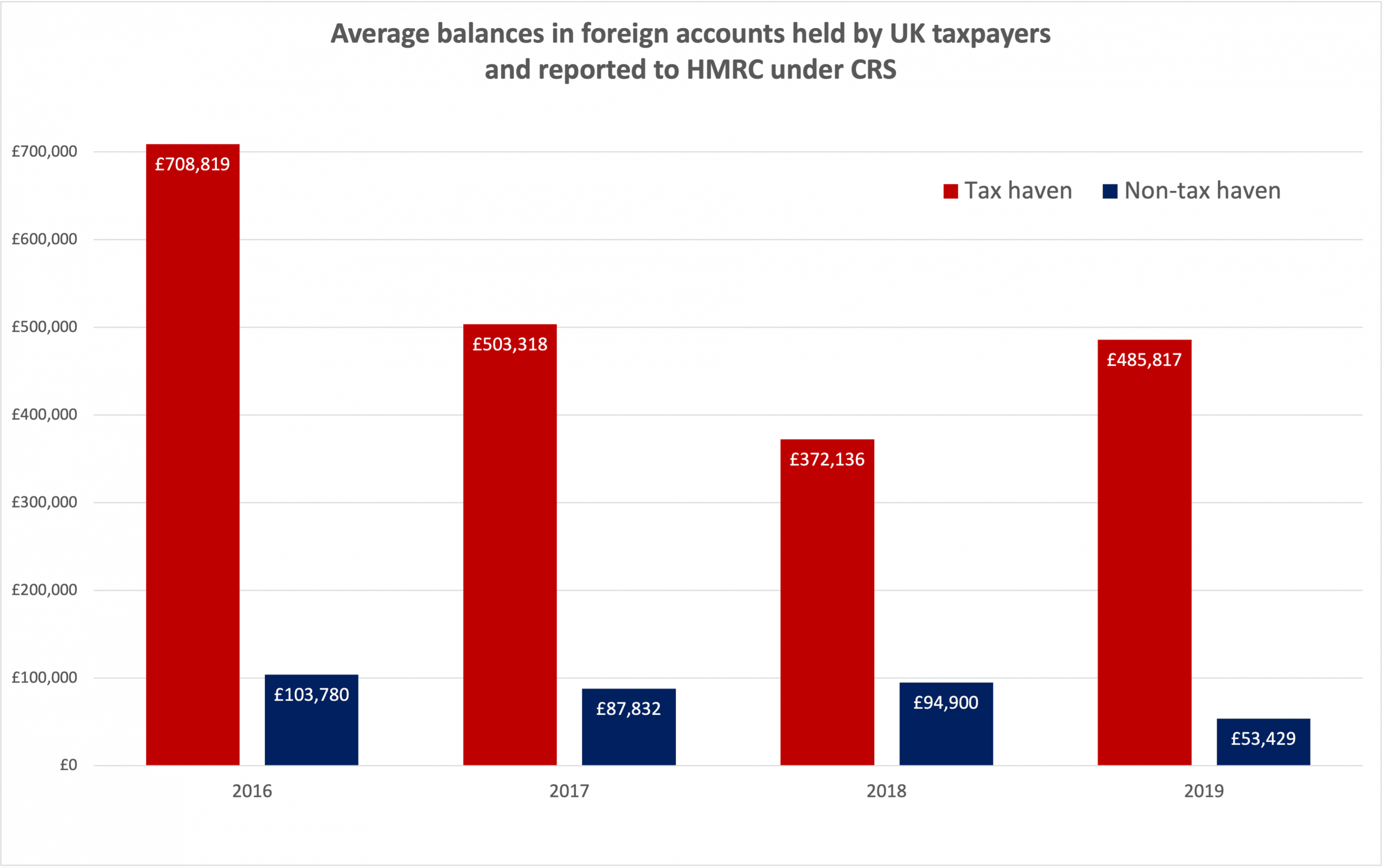

The amounts are very large – in 2019 UK taxpayers had over £850bn in foreign accounts, of which £570bn was in tax havens – see chart above (and my definition of “tax haven” below). And the average account size in tax havens is considerably larger than the average in the rest of the world1A tax professional with a huge amount of experience in this area made the excellent point that we need to be careful to distinguish actual account holders vs UK controlling persons of companies (“Passive NFEs”) are accountholders. Otherwise we can be double or multiple counting – i.e. because one company can have multiple controlling persons, and some of those (trustees) won’t be taxed on the account. My FOIA should have extracted the accountholders only, but absent full disclosure by HMRC it is possible they have mistakenly given me UK controlling person data as well:

Update: the FT story on our report is here.

Why is it important to have an estimate of the proportion of the £570bn that reflects tax evasion?

Because the scale of the estimate has enormous public policy implications.

If 30% of the accounts are undeclared (as some have previously suggested), then it’s a massive scandal and immediate action of the most serious kind will need to be taken. I’d say the same if the figure were 3%.

If, on the other hand, it’s 0.1% then all we should expect is efficient and effective HMRC enforcement.

The options

When HMRC started receiving this data back in 2016, it had several options:

- The traditional approach. Build a computer system to cross-check the CRS data with everyone’s tax return, to see who has an offshore account on which they’ve received income that wasn’t declared on a tax return. Version 1.0 doesn’t need to be very expensive or complex – just pull out matching tax IDs (national insurance numbers or UTRs) from the two sets of data, where CRS data indicates large tax haven accounts but nothing is declared in the “offshore income” section of the tax return. See what comes out. Build up the complexity and sophistication from there.

- The quick option. Set a bunch of junior tax inspectors to work manually pulling out a random sample of say 1,000 high-value individual CRS accounts in tax havens, locate those individuals’ tax returns, and look for anything suspicious. Then apply statistical tools to the result so you can estimate the overall level of non-compliance (albeit with significant uncertainty). Use that to inform whether you build a big system to automate this, and how you do it. Or maybe you find it’s slim pickings, and so just continue random manual checks for the largest accounts.

- The nerd option. Anonymise all the CRS data, hashing names, addresses, and tax IDs. Do the same with the overseas income section from tax returns. Hand both datasets over to a bunch of smart academics and data scientists, so they can do all the hard cross-checking for you. For free.

- The Thatcherite option. Do the anonymising thing again. But ditch the nerds – instead, offer private sector companies the chance to crunch the data and identify tax evaders, in return for payment of 10% of tax evasion recoveries. The nerds could apply too.

- The implausible option. Don’t do any cross checking, automated or manual, large scale or small scale. Make no effort to match up CRS data with tax returns.

Right now it’s unclear quite what HMRC have done – they’re refusing to say. They’ve told the FT’s excellent Emma Ageyemang that they “systematically” check the CRS data, but won’t reveal more. We can speculate they’re looking only for huge anomalies (e.g. millions in CRS accounts but nothing in a self-assessment return) but not cross-checking everything (or they would surely say so).

That speculation is consistent with the letters we know HMRC have sent to people with foreign accounts disclosed under CRS, reminding them of their responsibility to declare foreign income. HMRC has made clear these letters are sent on the sole basis of the CRS data, and without cross-checking with actual tax returns.

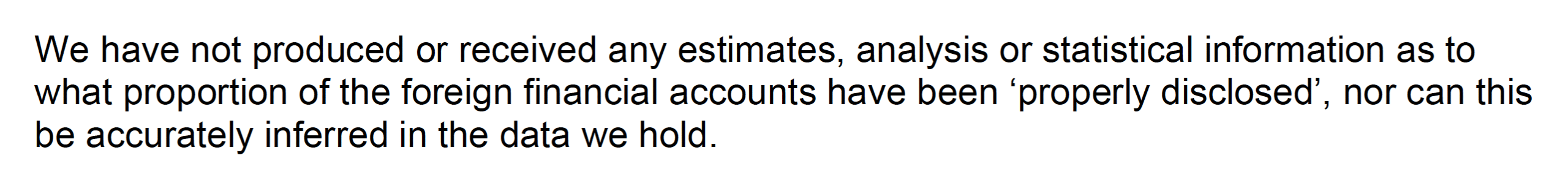

What is clear is that HMRC have made no attempt to estimate the scale of the offshore tax evasion problem, or even determine if it is a problem. The FOIA response says:

Why?

We’ve had several justifications from HMRC.

First, in the FoIA response:

“A number of the accounts reported through the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) are not actually chargeable to UK tax, nor is every account of a suitable value to impact on a persons’ UK tax position”

These, and many other factors, are why the CRS data has to be used with care. They are not reasons to discard the statistical value of the data altogether. You’d expect any kind of audit or cross-check to exclude non-taxable accounts and low-value accounts. (Although the obvious reason why some accounts of UK residents are not taxable is that they are held by non-doms, and given HMRC normally receives no data at all on non-doms’ foreign assets, you’d think this itself would be very useful data.)

Second, when speaking to the FT, HMRC said:

Not all of the worlds’ jurisdictions are signed up to CRS and we could not say with certainty whether each account was ‘properly disclosed’. We would not publish a figure where we did not have certainty that is accurate.

Here HMRC seem to be taking the odd position that no estimate can be made unless it is certain to be accurate. That is not what the word “estimate” means, and statistical methods have been developed to deal with errors for at least two hundred years.

HMRC is certainly familiar with producing estimates which are highly uncertain – they do so very competently in their annual tax gap report. This contains estimates for tax evasion and avoidance which have very large uncertainties – HMRC describes them as the “best estimates based on the information available”. And that’s fine. What’s not at all fine, and in fact inexplicable, is using uncertainty as a reason for making no estimate at all.

Furthermore, the stated reasons for uncertainty do not seem very hard to overcome. Whilst there are some jurisdictions not signed up to CRS/FATCA, they are generally ones where rational tax evaders would not risk keeping funds. They’d make any estimate a baseline/lower bound, but that would not diminish its usefulness.

“Properly disclosed” is also not terribly challenging to overcome. For example: focus on CRS accounts where the income/gains is larger than the annual exemption, and where there is a straightforward national insurance number/UTR match with the tax return of a taxpayer who is not a non-dom. Again that would result in a lower bound estimate, but still a useful one.

So HMRC’s explanation for the lack of any estimate doesn’t make sense.

Can we use other sources to estimate how much of the £570bn reflects tax evasion?

I don’t think we can – which is why HMRC’s failure to product estimates is so unfortunate.

I am very sceptical of some of the claims that have been made that over 30% of offshore accounts are undeclared. Tax authorities have now had the CRS data for five years or more, those that aren’t asleep at the wheel have been cross-checking against tax returns, and there have been a handful of prosecutions rather than thousands. And the existence of CRS means that pre-2016 estimates are of limited value.

It’s also important to remember that there can be many entirely legitimate reasons for having a financial account in a tax haven:

- Private equity funds, hedge funds and other types of non-retail funds are very commonly established in tax havens (most often Jersey, Bermuda, Guernsey and the Cayman Islands). As with most investment funds, the investors expect to pay tax on their return from the fund, but don’t expect the fund to also pay tax – that would be double taxation. You could achieve this in e.g. the UK with a great deal of work, but is much, much easier in a tax haven. So this isn’t tax avoidance – it’s tax lawyer avoidance. I expect a substantial part of the £570bn reflects fund holdings, and that almost all of this is properly declared to HMRC.

- Corporate joint ventures often use tax haven companies for the same reason – preventing double taxation is just easier/cheaper.

- Many companies will have legitimate business in some of the tax havens, e.g. shipping companies in Panama, lots of companies in Hong Kong and Brazil.

- Non-doms who are trying to avoid taxable remittances will often do so with a tax haven account. I don’t like the non-dom regime, but given we have that regime, they’re making a legitimate choice.

- Some of the tax havens have sizeable ex-pat populations in the UK, who have excellent reasons for retaining their home bank accounts.

But historically tax haven accounts were certainly used by the wealthy to hide assets away from tax authorities. Chances are some people are still doing this, whether because they are too disorganised to appreciate the risk of CRS, have some legal impediment which prevents them reacting to the risk (e.g. missing documentation), or are gambling that HMRC won’t spot them.

So I would be equally sceptical of any claim that there is no evasion hidden in the £570bn.

Are most of the offshore accounts held by non-doms?

Plainly not. The FOIAs show over a million tax haven accounts held by UK taxpayers in 2019. In that same year, there were fewer than 100,000 non-domiciled taxpayers claiming the remittance basis (i.e. for whom offshore accounts have a permitted tax benefit).

What should happen now?

In the interests of transparency, HMRC should publicly commit to:

- Annually publishing aggregated CRS statistics, such as number of accounts, and the mean and median balances. It shouldn’t take FOIAs to extract this information.

- An initial analysis of the CRS data, with – as a first step – the aim of estimating the proportion of accounts that haven’t been declared in tax returns. Any such estimate will be highly approximate, and number to numerous uncertainties. The HMRC tax gap report ably deals with much more difficult uncertainties (“unknown unknowns”); this is straightforward by comparison (“known unknowns”).

- Publishing the result of that analysis (minus any details that could assist tax evaders).

- Sharing the two key datasets: CRS data and the self-assessment foreign income returns – with academics, with suitable measures in place to protect taxpayer confidentiality.

- Equivalent measures for FATCA.

- To assist the ongoing public debate about the non-dom regime, publish the total balance of foreign accounts disclosed under CRS which are held by non-doms, the number of those non-doms, and the median account balance.

HMRC obviously should not reveal precisely how it uses CRS data, but it should be open about the results. How much additional tax has been collected from investigations sparked by CRS? How many penalties and prosecutions have there been?

This transparency is important for three reasons: keeping HMRC accountable; deterring tax evasion; and bolstering public faith and confidence in the tax system.

Full details

Everything is in three FoIA responses. The first reveals that the total amount held by UK taxpayers in foreign accounts is £850bn, the second says that £570bn of this is in tax havens, and the third admits that no effort has been made to estimate the proportion of CRS accounts which are undeclared to HMRC.

HMRC prefers not to use the term “tax haven”, so I defined the term using a particular technical definition which covers the following countries: Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Colombia, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Curacao, Faroe Islands, Gibraltar, Greenland, Grenada, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Isle of Man, Jersey, Korea, Lebanon, Lichtenstein, Macao (China), Mauritius, Monaco, Montserrat, Niue, Panama, Samoa, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Vanuatu.

That’s not a perfect list of tax havens (I’d exclude Brazil and include Switzerland and possibly Singapore), but it’s a good approximation.

The data covers all financial accounts (cash bank accounts, security custody accounts, interests in investment funds) held by UK resident individuals and corporates that are not financial institutions.

This is CRS data only, and so doesn’t include accounts in the US, as the US reports under a different set of rules (FATCA) and HMRC wasn’t willing to disclose anything about the FATCA data it had received. So the actual total for non-tax haven accounts is likely much higher than the figures above.

-

1A tax professional with a huge amount of experience in this area made the excellent point that we need to be careful to distinguish actual account holders vs UK controlling persons of companies (“Passive NFEs”) are accountholders. Otherwise we can be double or multiple counting – i.e. because one company can have multiple controlling persons, and some of those (trustees) won’t be taxed on the account. My FOIA should have extracted the accountholders only, but absent full disclosure by HMRC it is possible they have mistakenly given me UK controlling person data as well

2 responses to “Tax Policy Associates report: UK taxpayers have £570bn in tax haven accounts, and HMRC has no idea how much of this reflects tax evasion”

HMRC’s reasons for refusing to provide data derived from the US seem spurious. They claim that “Information about exchanges under international tax instruments is confidential both under the terms of relevant instruments and because other states have an expectation that this information will remain confidential”. The UK-US tax treaty under which the FATCA operates says that information received “shall be treated as secret in the same manner as information obtained under the domestic laws of that State”. It’s hard to see why this should apply to large scale aggregate data of this kind. It seems more likely that the US wants to keep FATCA data secret, not least because it would reveal the imbalance between countries such as the UK which have negotiated a bilateral FATCA agreement, and those that simply provide information to the US.

It’s not just FATCA – HMRC have refused to provide any information which relates specifically to any CRS country or small group of CRS countries. There seems to be obsessive secrecy relating to all things FATCA and CRS. I am working on it!