There’s speculation today we might see a stamp duty/SDLT “holiday”.1Apologies to all tax professionals, but I’m going to call SDLT “stamp duty” throughout this article.2 What effect have previous “holidays” had?

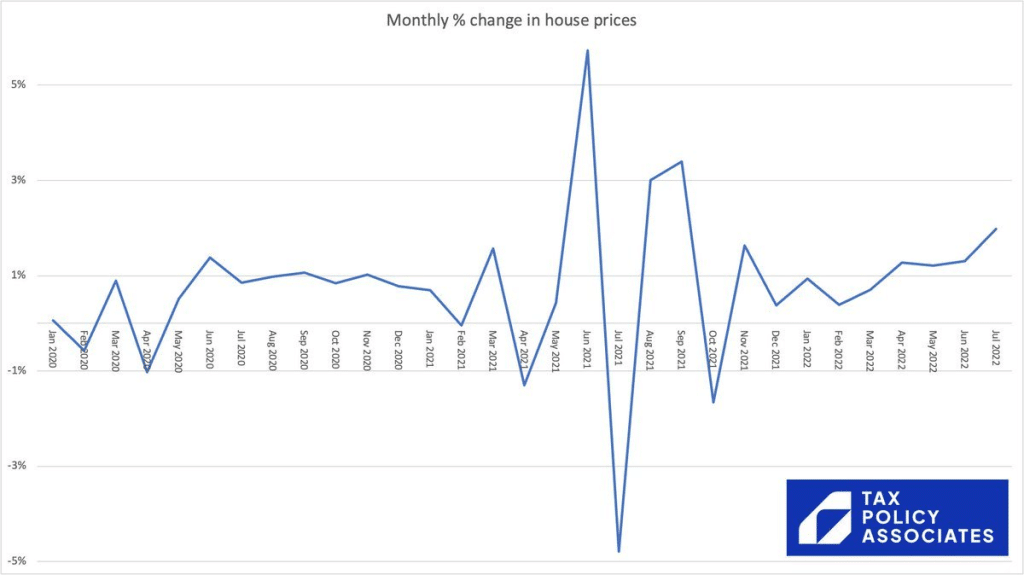

Here’s a chart showing changes in the average UK house price.

Guess what triggered the heart attack in the middle?

The big spike in June 2021 just happens to coincide with the last month of the £500k stamp duty “holiday”:

- Buy a £500k property in June 2021: £0 stamp duty.

- Buy in July 2021: £12,500.

So a nice stamp duty saving equal to 2.5% of the purchase price. But the chart shows a 5% price hike in June 2021, so – overall – buyers lost out. And the 2.5% figure is only achieved by properties worth £500k – the saving will be smaller for both cheaper and more expensive properties.

Then another price spike before the end of the £250k nil rate band in October:

- Buy a £500k property in September 2021: £12,500 stamp.

- Buy it in October: £15,000.

A stamp duty saving worth 0.5% of the house price – again swallowed by house price increases (and again for most people the average stamp duty saving would be less than 0.5%).

These look like irrational results: buyers would have been better off waiting til the “holidays” ended. That’s not necessarily right. Possibly lower stamp duty but higher house prices benefits buyers (as they can get a mortgage against the house price but not the stamp duty).

But irrationality is also likely a cause here – the desire to get your purchase in before the end of the holiday created a demand crunch with a dynamic of its own, even though waiting a week could have reduced overall costs.

These two factors, plus the “stickiness” of house prices mean that, even when the holiday is over, the increase in house prices appears to stick.

Previous stamp duty holidays had less dramatic effects: there’s good evidence that the 2008/9 stamp duty holiday did lead to lower net prices, but 40% of the benefit still went to sellers, not buyers. There’s some published research on the 2021 holiday, but it was completed too soon to catch the September heart attack. I’m not aware of anything more recent.

So all of this suggests stamp duty holidays are a bad policy, an inefficient way of helping buyers, and perhaps even triggering price rises greater than the tax saving.

A permanent stamp duty change shouldn’t have so dramatic an effect *if* people believed it was permanent. But a chunk of the benefit would still be swallowed up in higher prices. And from a distributional point of view, stamp duty cuts are a way to hand money to those who already have it.

The bigger picture: residential stamp duty is a terrible tax because it discourages people from moving house when otherwise they’d want to. I’d scrap it, and replace the c£10bn of revenue with increased council tax on high-value properties (not hard, when council tax raises £42bn). In principle that would prevent the stamp duty cut from fuelling house price inflation.

But, whatever your view about the future of stamp duty, a “holiday” looks like a mistake.

Photo by David Vives on Unsplash

- 1

- 2

3 responses to “Why stamp duty “holidays” are counter-productive”

I’m not sure I agree with you Dan.

I don’t think that the success or otherwise of the July 2020 change can be judged on its impact on house prices. The chancellor said “So to catalyse the housing market and boost confidence, I have decided today to cut stamp duty”. Thereferore, who shares the benefit of this reduction does not seem to be a measure of the policy’s success.

This reduction was from July 2020 until (after being extended) September 2021. The context was that there had been a lock down, employees were being furloughed (or laid off) and many self-employed individuals were suffering a reduction in income. This meant many people were more cautious and less likely to move. Other people may have been more likely to move because they wanted to be in a bigger house and/or more rural location after being locked down. This will have an impact on house prices but you don’t mention this type of thing as a factor and just sight irrationality or the potential impact of stamp duty on getting a mortgage.

To know whether the policy was a success, you need to look at whether the reduction increased the number of transactions compared with a counterfactual. I don’t see that you have done that. It may be that transactions increased tenfold compared with what would have been the case in the midst of covid and job uncertainty. In that case, the policy would have met its objectives. Perhaps, the focus on reducing transaction costs focused minds on moving and there was also irrationality. I have no idea. But that doesn’t mean the reductions countered the policy objective.

Is this something to do with you then? https://fairershare.org.uk/proportional-property-tax/ I agree with it

nothing to do with me. Looks a bit rubbish. High % tax on the *improved* value of property is a bad idea. Naive to think none of it gets passed onto tenants. The authors should read up on the land value tax.