We’ve reviewed multiple Property118 client files to investigate how they implement their tax avoidance scheme. We’ve found that the scheme is implemented so badly that our previous criticism is beside the point – a key drafting error means that the scheme fails immediately. It also appears that their clients receive templated “advice” which fails to identify key issues, or warn clients about the legal and tax risks they are running.

We’ve been reporting on a tax avoidance scheme promoter called “Property118”, which has sold over 1,000 tax avoidance schemes to landlords. The essence of the scheme is to obtain the tax benefits of incorporating a property rental business without the usual tax and commercial downsides. The scheme involves artificial steps with no purpose other than tax avoidance.

We previously concluded that the structure had significant technical flaws which meant that it likely did not work. However, this analysis assumed the structure was correctly implemented. It isn’t. We have now reviewed complete sets of Property118 advice and documentation, and there are very significant failings in both legal implementation and in Property118’s advice.1It’s relevant to note that a court or tribunal would not necessarily approach the Property118 structure point by point, in the way that we have analysed in our reports. In a recent podcast discussion on the Property118 structure, Patrick Way KC made the important point that, when a structure looks like tax avoidance, the modern judicial approach is to find against it on principled grounds and not undertake the full technical analysis.

- The most important document implementing the structure appears to be defective. A trust deed that is supposed to create a bare trust actually reserves rights for the landlord, and so likely creates a taxable settlement. This has complex and highly deleterious consequences for the landlord.

- There is another series of drafting errors around the indemnity which supposedly enables a company to claim mortgage interest tax relief. The documents are contradictory, and either don’t create an indemnity at all, or accidentally create a stream of taxable interest payments.

- A key tax consequence is whether the structure is disclosable to HMRC under DOTAS. It appears that Property118’s associated barristers chambers, “Cotswold Barristers” never considered this point until we raised it. The head of Cotswolds Barristers, Mark Smith, then published an article that the HMRC official who introduced DOTAS described as “hopelessly wrong”. Our view is that anyone who wrote that article is not competent to advise on tax.

- Cotswold Barristers appear to never advise on the application of anti-avoidance rules to their structure.

- Cotswold Barristers don’t appear to review their clients’ mortgage terms and conditions, despite promoting their scheme on the basis it is compliant with mortgage T&Cs.

- Cotswold Barristers have provided entirely incorrect technical advice to clients they’ve advised to use a “mixed partnership” structure. The advice missed a key section of the legislation.

- The documents and advice are almost identical for all clients – Mark Smith and Property118 use very standardised templates.

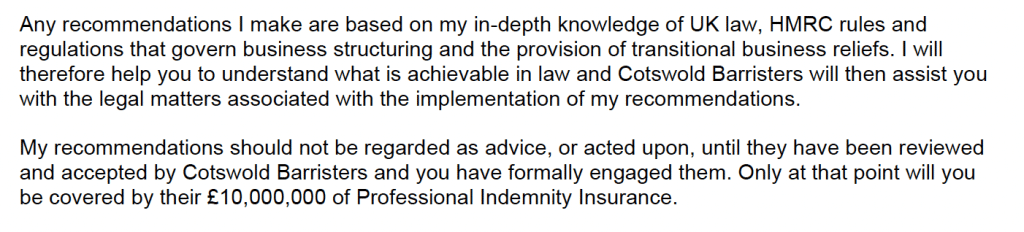

- Cotswold Barristers appear to mostly “rubber stamp” advice provided by unqualified “tax consultants” working for Property118. Nevertheless, fees of £30-70k are typically charged for implementing the structure.

- Tax advice usually draws clients’ attention to risks, whether large or small. Cotswold Barristers never mention risks of any kind, legal or tax.

- Instead, the clients are told that the barristers have £10m of insurance “per client” and therefore the clients are “shielded from financial risk”. This is not true. It’s not £10m “per client” – it’s effectively £10m across all 1,000+ clients. And in any case, professional insurance does not “shield clients from financial risk”. To access the insurance, clients have to successfully sue the barrister for negligence – which is far from straightforward.

- It is unclear whether Mark Smith, the only named member of Cotswold Barristers, has the qualifications or experience to advise on tax.

We explain these points further below.

If Property118 have really sold their scheme 1,000 times, and the documents are as standardised as they appear to be, then all 1,000 schemes will have failed. Not just failed because of the technical analysis in our previous article, but failed because of incompetent implementation. We believe many of the clients entered into the scheme on the basis of assurances about Mark Smith’s insurance which were false.

Given the scale of the problem, we believe it’s important that taxpayers and HMRC resolve these issues now, rather than years later, when the situation could become a loan charge-style crisis. We will also be asking the Bar Standards Board to investigate.

As ever, we will promptly correct any errors of fact or law that are identified; however we will not withdraw any statement we make because of threats of defamation proceedings, childish insults or vague and generic articles that fail to address our specific points.

A defective trust document

Central to the Property118 scheme is that the landlords declare a trust over their rental properties in favour of a newly incorporated company. Here’s the description of the deed of trust in Mark Smith’s advice:

So this is intended to be a “bare trust” – the company/beneficiary holds absolutely and the landlords are mere trustees. The company would then be taxed more-or-less as if it held the properties directly.

The first operative clause in the trust deed intends to achieve that:

But then, three clauses later, we see this::

This clause has astonished every lawyer who’s seen it. It enables the landlords/trustees to reacquire the property for no payment – but that’s entirely incompatible with a bare trust, where beneficiary absolutely owns the property.2This is the only meaning we can see “vest absolutely and immediately in the Trustees” can have. It is unclear what “in accordance with their various legal and equitable interests” means, given that a trustee obviously has no equitable interest. Possibly it means that the Trustee takes the same % beneficial ownership as they had before the trust was originally declared.

We have considered whether this could simply be a typo, and 2.4 should be read as meaning that the Property vests “absolutely and immediately in the Beneficiary“, but we don’t think that can be right. First, the property has already vested in the Beneficiary, so it doesn’t make sense to say that the Trustee can by notice vest it again. Second, it would be odd for the Trustee by notice to trigger its own loss of legal title. Third, the “or” clause at the end of the paragraph deals with the scenario where the Beneficiary has called for legal title; why would there be two subclauses doing the same thing? We therefore don’t believe the wording can be ignored, no matter how inconvenient it may be. The drafting is clearly a mistake from a tax perspective, but that doesn’t mean it can be ignored – there is, after all, commercial utility to enabling the landlord to unwind the structure at any time. It might be possible to make an application to the court for rectification on the basis there was a mistake of law and/or mistake of tax law, but this would be far from straightforward.

We have spoken to a range of trust and trust tax experts, and we believe there are three principal possibilities:3James Robertson added another point we missed in our initial analysis: the potential for an up-front market value CGT charge under s284 TCGA (sale with a right to reconveyance). The interaction between the different provisions would require considerable thought, but likely there would be only one up-front market value CGT charge, whether under the settlement rules, s284 or on the grant of an option.

- Clause 2.4 gives the landlord/settlor an interest in the trust, which means it is a settlement for tax purposes. This seems the most likely outcome.4This is the view of our team (including a KC specialising in the tax treatment of trusts), but should not be regarded as the final word; a definitive analysis would require consideration of the full facts and circumstances, and it would be wrong at this stage to preclude the other two possibilities.

- The trust is a bare trust, but Clause 2.4 gives the landlord/trustee an option to reacquire the beneficial interest at any time. We believe this is unlikely given that clause 2.4 is part of the trust, not an ancillary contract.

- The trust could be void and/or ineffective for tax purposes. We believe this is unlikely, given that the meaning of the document is clear, even if its tax effect is undesirable.

The first two scenarios result in an up-front capital gains tax charge as if the properties were sold for market value5The grant of an option is immediately subject to CGT. As the parties are connected, the consideration will be deemed to be market value, and the market value of an option to acquire the properties at any time for free will be (broadly speaking) the current market value of the properties. The transfer of property to a settlement triggers an immediate CGT charge at current market value. A settlement would also give rise to complex ongoing tax issues.6Including the settlor interested trust rules effectively reversing any potential income tax benefit, and a 6% inheritance tax charge every ten years. Possibly also a 20% entry charge, and the application of the gifts with reservation of benefit rules, although this would need a careful analysis which we have not undertaken. If a settlement arises then it would have to be registered with the Trust Registration Service. Mark Smith takes the view that the intended “bare trust” is not registrable – we are not sure that is correct, but it’s irrelevant if in fact the trust is not bare.. The third scenario might be a welcome one, as possibly it provides a way to take the position that the whole transaction had no effect.7This would, however, need careful thought. It would be very inadvisable and perhaps improper to simply proceed on this basis without detailed and case-specific legal analysis. In all three scenarios there is no possibility of the company claiming a tax deduction for mortgage interest, because you don’t “look through” a settlement in the way you look through a bare trust.

However, regardless of which of these three scenarios apply, none result in the structure intended by Property118 and Cotswold Barristers. The scheme is dead on arrival, and our previous analysis of the structure is no longer necessary (or indeed relevant);8i.e. because our previous analysis was on the assumption that Property118 correctly implemented their structure. We also note that, when Property118 briefly hired a tax KC in an attempt to threaten us with a libel suit, it seems likely that she did not review the transaction documents, as she said specifically that her views were on the basis that the structure was “properly implemented” – see paragraph 13 here. The KC did add that she had reviewed client files, but we expect this was advice and correspondence with HMRC, not transaction documentation – if the KC had reviewed transaction documentation then we believe her opinion would have been very different.

It is not uncommon for tax avoidance schemes to fail because of incorrect implementation. For example, the Vardy stamp duty/SDLT avoidance scheme involved an unlimited company paying a dividend ‘in specie’ of the real estate itself, and claiming that the dividend was outside SDLT. This was probably destined to fail, but it didn’t even get that far. The dividend wasn’t properly declared and was unlawful.

So far as we are aware, on the basis of the Property118 documents we’ve reviewed and the documents reviewed by advisers we’ve spoken to, this error is present in all Property118 documentation.

We do not believe a reasonably competent tax lawyer would have drafted a trust deed in this manner – it is basic trust law that the beneficiary of a bare trust has an absolute entitlement to the trust property, and no other party has any entitlement. The drafting therefore suggests that Cotswold Barristers may have been negligent.

The misdrafted indemnity

The central point of the structure is to solve the “section 24” limitation on landlords claiming mortgage interest tax relief. The idea is that the landlord continues making interest payments to the mortgage lender, but these are funded by the company, which can claim a tax deduction.

Here is how Mark Smith describes this in the “client care” letter he sends to accompany the draft documents:

The drafting to achieve this is a mess of confused and contradictory provisions.9In the interests of simplicity, this analysis in this section of our report ignores the first drafting error – the fact the trust is probably a settlement and not a bare trust. In reality the interaction of the two issues would need to be considered, and that is not at all straightforward.

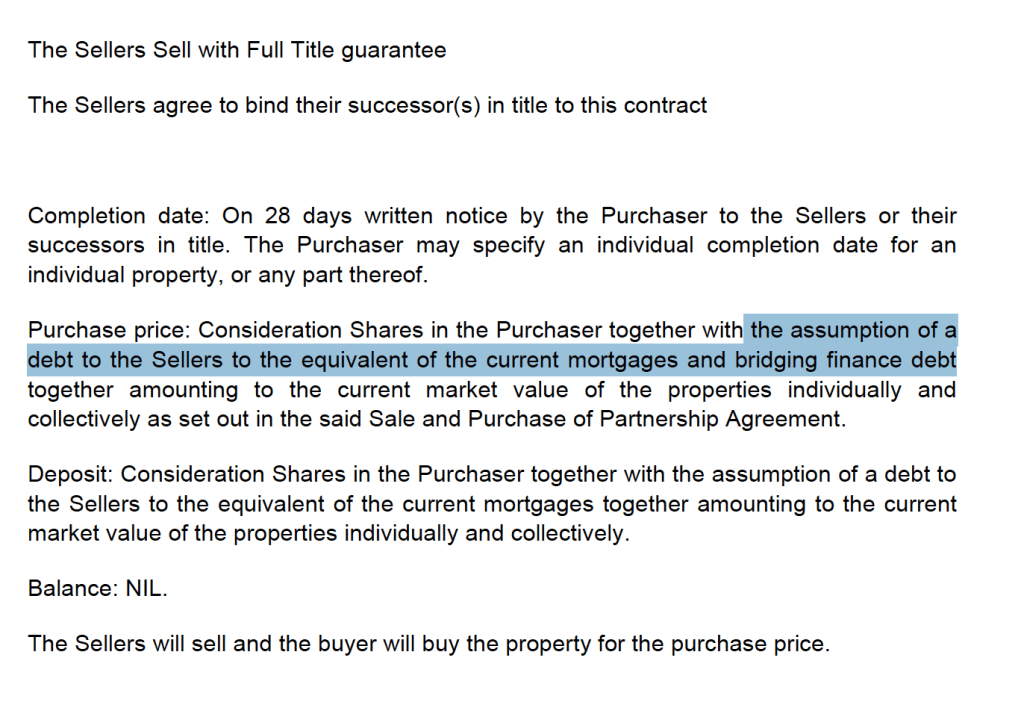

First, the Business Sale Agreement contains no indemnity. Instead it says:

The definition of “Liabilities” lists the outstanding mortgages. But law students usually learn in their first contract law class that English law doesn’t permit the purchase of liabilities. In some circumstances you can buy assets in consideration for an assumption of liabilities – but that won’t work here, because the mortgage lender won’t permit the company to assume the liabilities.10And is likely entirely unaware of the transaction.

The sale contract for the properties contradicts this:

In other words, the landlords continue to owe the mortgage to the lender (as they must), but the company now owes an equivalent debt to the landlords. That is a sensible approach, but legally different from an indemnity. It creates an obligation for the company to pay a principal amount to the landlord, but doesn’t create any obligation for the company to cover the landlord’s interest payments

There are then three very confusing clauses:

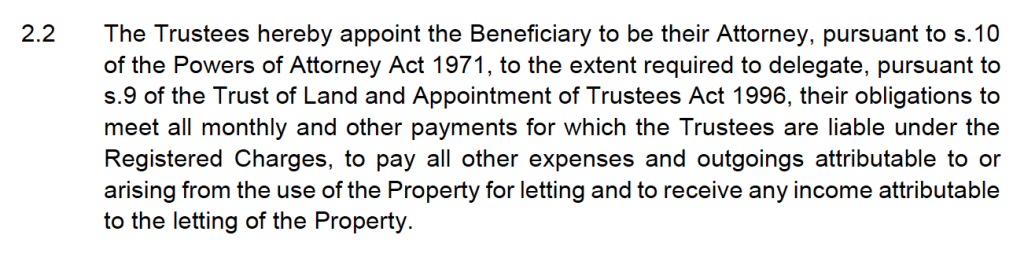

First, an attorney/delegation clause in the trust deed, under which the landlords appoint the company as their attorney to make interest payments on their behalf:

This normally won’t be permitted by the terms of the mortgage; only the borrower can make payments, and as a practical matter a lender would usually reject payments from another party. We don’t know why it’s included.

Then an indemnity in the trust document:

Does this cover the landlord’s mortgage interest payments? Unclear.11Our team had different views. Some of us believe the clause could be read broadly, given that the trust anticipates the existence of the mortgages. Others don’t agree, because the mortgage payments are not “chargeable on the Property” (rather, they are personal obligations of the landlord), and the mortgage payments do not “arise out of the settlement” (also, what does “payable to them” mean? The word “to” looks like a typo, but it’s included in all the versions of this document we’ve seen).

There is then an “agency agreement” with recitals as follows:

Unusually, recital B is the only operative term in the contract12Usually lawyers never put operative provisions into recitals, but where a contract is silent on a point, an operative provision in the recitals will be effective – see the old case of Aspdin v Austin (1844).

So, to recap: under the original mortgage, landlord has an obligation to pay interest to the mortgage lender. Under Clause 2.2 of the trust deed, the landlord delegates the making of these mortgage payments to the company. Under the agency agreement, the company then appoints the landlord as its agent to make the same payments – back where it started. We have no idea what the point of this is. Neither provision will have any tax effect – agency/delegation doesn’t normally change the tax character of a payment (because a payment by an agent or delegate is, for most tax purposes, regarded as made by the principal).

It’s a mess.

However, landlords may be better off if these provisions don’t create an obligation for the company to make indemnity payments in respect of the mortgage interest. First, given the debt created by the sale contract, the payments are likely to be “interest”13The fact the indemnity payments are not termed “interest” in the documents is irrelevant (see the Re Euro Hotel case) – economically they are interest on the principal amount created by the sale contract and therefore are interest for tax purposes (see Bennet v Ogston). Probably they would not be interest even if there was no principal amount – our original view (prior to having reviewed the document set) was that they would be either taxable annual payments or capital payments (i.e. sale consideration). for tax purposes, subject to 20% withholding tax, and additional income tax in the hands of the landlord. Second, the payments are unlikely to be deductible for the company (they are probably not payments under a loan relationship; if they are, the existence of a tax main purpose means they will be non-deductible).

In our view, a reasonably competent lawyer would not have drafted such a web of contradictory and confused clauses.

Incompetent advice on DOTAS

As we will discuss below, Cotswold Barristers rarely provide any advice on any tax issue. One of the many issues they do not discuss is DOTAS – the rules requiring a promoter of a tax avoidance structure to disclose it to HMRC.

We criticised this in our original analysis. Six weeks later, Mark Smith responded with an article that provided technical justification for a claim that DOTAS does not apply (link is to an archived version; it’s no longer on the Property118 website). This is important, because it is the only technical analysis we or any of our sources have seen from Mark Smith, and it therefore lets us assess his competence.

Smith’s article was reviewed by Ray McCann, a retired senior HMRC official. When Ray was at HMRC, he led the introduction of DOTAS. Ray described Smith’s article as “hopelessly wrong”.

Smith made the following serious mistakes, which call into question his basic competence.

- The article contains a lengthy argument that the scheme is not “tax avoidance”. This is technically irrelevant. DOTAS turns on whether an arrangement’s “main benefits” include obtaining a tax advantage. It is reasonably clear that tax is one of the main benefits of the Property118 structure; indeed it is not obvious what the other benefits are.14This is not the case for a normal incorporation, which achieves other objectives: e.g. segregating liability and obtaining commercial financing – however the Property118 structure does not achieve this Smith conceded that there is a tax main benefit, but in such a way that a layperson will not notice the importance of the concession.15And Smith did not then consider any of the many anti-avoidance rules which will be engaged if there is a tax main benefit or tax main purpose

- Mark Smith said Property118 was not a promoter because “CB is solely responsible for the design of the [structure], in the sense that any issues arising from the design would lead solely to CB being held accountable”. This is not correct. Property118 makes an initial structural proposal to clients, and therefore is “to any extent” responsible for the design of the scheme. Who is “held responsible” is irrelevant (although why Smith thinks Property118 wouldn’t be legally responsible for their own actions is a mystery).

- It appears Mark Smith believed that he could not be a promoter because of legal privilege. But there is no absolute DOTAS exemption for lawyers; the question is whether the “prescribed information” required to be delivered under DOTAS would breach legal privilege. Given the generic nature of the scheme, it is possible (depending on the precise facts) that DOTAS reporting would not in fact breach legal privilege, and Cotswold Barrister and/or Mark Smith is a promoter.

- Property118 markets, online and in person, a scheme that has a well-established design – and that makes them a promoter. Smith refers to the Curzon case, but that involved a mere administrator – it’s irrelevant. Anyone marketing a scheme will almost always be a promoter for DOTAS purposes.

- Smith then concluded the scheme is an “in-house” scheme. This is a complete misunderstanding of the term. An “in-house” scheme is where a company devices and implements its own avoidance scheme. That is not at all what is happening.16Smith misses that there are several ways in which there can be no promoter: (1) in-house schemes, clearly not relevant; (2) the promoter is outside the UK, not relevant; and (3) no promoter. If Smith was right that Property118 wasn’t a promoter then this would be the third scenario, not the first. He makes a bad mistake and is then badly wrong on the consequences of his mistake.

- Having applied the wrong set of rules, Smith then doesn’t consider if there’s a premium fee (which there obviously is). Smith says the “financial product hallmark” doesn’t apply to his scheme because the “scheme isn’t a financial product”. That isn’t the test. The question is whether the arrangement includes a financial product. The bridge loan obviously is a financial product. The indemnity enabling the company to achieve a tax deduction is be a financial product (if it exists)17And DOTAS looks at the “proposed arrangements”, and therefore the fact that Smith accidentally omits the indemnity is no defence. Both are probably “off-market” products, and therefore the hallmark applies.18The confidentiality hallmark would also likely apply, given that Property118 refused to disclose details of their scheme on the basis that it is “valuable intellectual property”

Mark Smith’s analysis therefore contained a series of elementary but serious mistakes. We believe it was incompetent. If Smith’s article is the basis on which he concluded DOTAS didn’t apply, or indeed if he had never previously considered DOTAS, then in our opinion he fell well below the standard of a reasonable tax barrister, and was negligent. It also leads us to believe he is not competent to advise on tax.

Smith’s article was heavily criticised by Ray McCann and others. At some point Smith reacted to this by silently rewriting his article, and removing the hopeless arguments that the scheme had no promoter and was an “in-house” scheme. Smith now relies upon three claims:

- The confidentiality hallmark doesn’t apply because they publish the scheme details widely. That’s not what Property118 told us – when we asked about the details of the structure we were told it was “valuable intellectual property”

- It isn’t a “standardised tax product” because they look at each case individually. But the documents and advice we’ve seen from Property118 and Cotswold Barristers have been completely standardised.

- There isn’t a “premium fee”. That is clearly incorrect for the “bridge loan” structure, where they charge a 1% “arrangement fee”. It also seems incorrect for the rest of their structure, where the fee varies from £30k to as high as £90k based upon the size of the landlord’s portfolio.

- HMRC have never raised this point across at least 20 “compliance checks”. We expect that is because they were not presented with the full facts.19A “compliance check” is not a tax term, but we are assuming these were “aspect enquiries” and not full enquiries.. Less Tax for Landlords told us their structure had been seen by HMRC on 40 occasions – but when HMRC became aware of the structure, they concluded it should have been disclosed.

- Smith doesn’t mention the “financial product” hallmark. This is a serious error. The bridge loan obviously is a financial product. The indemnity enabling the company to achieve a tax deduction is intended to give rise to a financial obligation for accounting purposes (or there would be no deduction) and is therefore a financial product. The loan and indemnity have the main benefit of creating a tax advantage, and wouldn’t have been entered into but for the tax advantage. The bridge loan and trust/indemnity are contrived and abnormal steps. The financial product hallmark therefore likely applies. We expect Smith failed to consider it because of his misunderstanding of the hallmark (evidenced in his original article).

This is therefore significantly less incompetent than Smith’s original article, but still contains bad errors of fact and law.

The consequence of DOTAS applying is serious for Property118 and (if he is a promoter) Mark Smith – penalties of up to £1m. There are also serious consequences for their clients: HMRC may have up to 20 years to investigate their tax affairs.

Incompetent advice on mixed partnership rules

We recently reported on the “hybrid partnership” scheme promoted by Less Tax for Landlords. HMRC has confirmed that the scheme does not work, and should have been reported under DOTAS. Property118 seemed delighted with that outcome, and said:

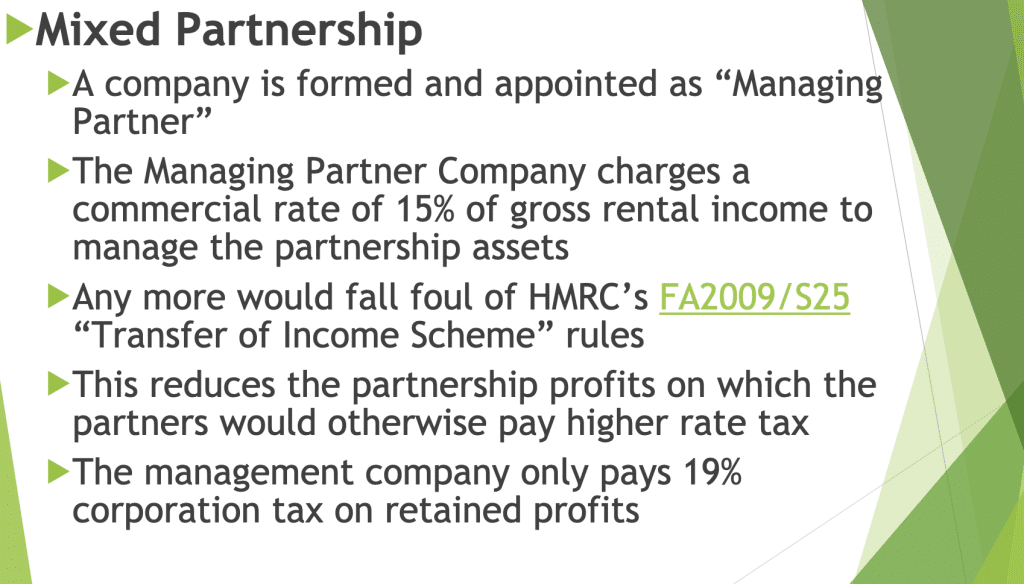

So it is surprising that Cotswold Barristers have endorsed a version of the same structure:

This slide has a series of errors:

- The “transfer of income streams” rules are in the Income Tax Act 2007, ss 809AZA–809AZF. As HMRC say in the Spotlight, section S809AAZA will apply to counter arrangements where the main purposes include the obtaining of a tax advantage (as they do here).

- There is no 15% rule in that Act or in any HMRC guidance of which we are aware.

- The mixed partnership rules also apply – broadly speaking, they counteract the diversion of income to corporate members of partnerships and LLPs. The 15% reference is perhaps meant to suggest that the allocation to the corporate member reflects an arm’s length return on services provided, and is therefore disregarded under section 850C(15) ITTOIA 2005. But where the services are personally provided by an individual member of the LLP then s850C(17) disapplies subsection 15. You can’t, in fact, allocate even 1% to the corporate member.

The failure to consider subsection 17 was in our view incompetent. A reasonable adviser reading the legislation would surely not have made that mistake.20As an aside, Smith tends to refer almost exclusively to HMRC guidance, and in this case the first guidance appearing on Google doesn’t mention the subsection 17 rule (probably because the guidance pre-dates the legislation). That is speculation; however it is notable that reliance on this out-of-date guidance was one of Less Tax for Landlords’ big mistakes.

Advice which is “templated” and fails to cover key points

Cotswold Barristers (which in practice means Mark Smith) advise their landlord client directly under the Bar’s public access scheme.

This is the claim made by Property118:21The reference to HMRC manuals is curious – advisers should be advising on the basis of the law, particularly when a transaction is tax-motivated (as HMRC guidance cannot be relied upon in such circumstances).

We have seen no evidence of any of this. The pattern we have seen, again and again, is that Property118 and Cotswold Barristers use standardised documents and provide highly standardised advice.22Which is why we are confident we will not reveal our sources by publishing extracts from Property118 advice and documentation In the cases we have reviewed, the written advice consists of four standardised communications:

- The initial proposal

The client pays £400 for an initial consultation.

They then receive a document from a “tax consultant” at Property118 (not a lawyer, accountant or CIOT/CTA qualified tax adviser) entitled “Incorporation and Smart Company structuring”.

This is a glossy document setting out the proposed structure, in a standardised form, including recommendations almost identical to this:23Note in passing that “a discretionary trust controlled by you” is not how discretionary trusts can work if they are to be respected for inheritance tax purposes.

It adds:

The document then sells the benefits of the structure, which are almost entirely tax benefits:

The fact there is an obvious tax “main purpose” means a multitude of anti-avoidance rules should be considered; there is no evidence they are considered at all.

The only tax advice contained in the document is a short and generic summary of CGT and SDLT relief upon incorporation.

2. Cotswold Barristers confirmation

If the client proceeds to instruct P118, they receive a letter from Mark Smith at Cotswold Barristers saying that he agrees with the recommendations in the initial proposal:

The letter then sets out a generic description of the structure and Smith’s terms of business.

There is no advice on any additional points beyond those in the original communication. We are not aware of any case where Mark Smith departs from the original Property118 advice – he appears to always “rubber stamp” the advice of the unqualified “tax consultant”.

3. Draft documents

The client then receives draft transaction documents, plus a one page cover letter entitled “Model client care letter” written by Mark Smith of Cotswold Barristers.

It explains the documents but contains no advice on the tax consequences of the arrangement. We excerpted above the incorrect descriptions of the trust deed and business sale agreement. Similar short descriptions are provided of the other documents.

4. Post-completion letter

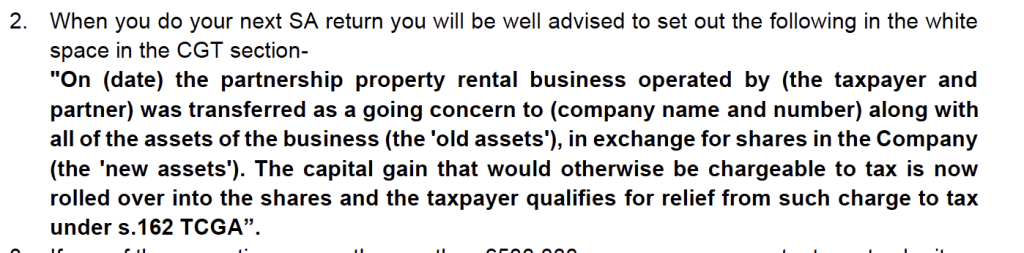

After the documents are signed, Mark Smith sends the client another “client care letter” confirming that the transaction has completed. The letter contains a FAQ and an explanation of the structure for conveyancers.

The letter is standardised, and it appears from the documents we have seen that only the salutation at the top of the page changes from client to client. The name of the new company is written as “(company name and number)”. The letter mentions the requirement to submit an ATED return “If any of the properties are worth more than £500,000”, even though Cotswold Barristers know that (in the cases we saw) they are worth significantly more than that.

The most hilarious example of standardisation is:

No advice is provided to the client in this letter.

Missing advice

It’s useful to look again at the original promises for the Property118 structure, made in the first communication:

Very little of this is covered by advice from Property118 or Cotswold Barristers. As far as we are aware, they never provide proper advice on the following key points:

Does the trust default the mortgage?

This is a hugely significant point for landlords. Property118 are very reassuring when making presentations, but when it comes to specific clients we have seen no evidence of any advice on this point. Most of their clients have multiple mortgages over different properties. There is no evidence of any review of the mortgage T&Cs in either the original Property118 advice or the Mark Smith letters. Mark Alexander now seems to concede that the structure legally defaults their clients mortgages:

A “technical” breach of mortgage T&Cs will in most cases entitle the bank to call a default and demand repayment.

Does CGT incorporation relief apply?

The first letter, from Property118, says it does, based upon a simple analysis of the facts. We would expect a barrister to then consider the technical analysis and, in particular, whether the fact legal title is not transferred means that there is a “sale of a business as a going concern”, and whether ESC D32 can be relied upon given that the transaction is tax-motivated.

There is no evidence of consideration of these points.

Cotswold Barristers make the serious error of advising clients to include incorrect disclosure in the client’s self assessment return:

This is an entirely incorrect description of the sale agreement, because it is a sale in consideration for shares plus the assumption of debt. That is highly material, because on the face of the legislation it prevents incorporation relief from applying. Reliance could then be placed on an HMRC extra-statutory concession, but that isn’t available in tax avoidance cases.

The description also fails to mention that the business is not being sold conventionally, but rather a trust is being declared.

The most favourable interpretation is that this is a serious error. The less favourable interpretation is that this is intentionally providing incomplete disclosure to HMRC to avoid alerting HMRC to the fact that incorporation relief may not apply.

In any event, the intended incorporation relief position is of merely academic interest given that the trust appears to be a settlement, which means an up-front CGT charge with no prospect of relief.

Does SDLT “partnership relief” apply?

Property118 and Cotswold Barristers claim that in many cases where a married couple jointly run a property rental business, they can retrospectively claim that a partnership always existed, and therefore incorporation benefits from SDLT rules that can provide relief for partnerships incorporating.

Technically it is very doubtful a partnership exists in most normal circumstances.

When Property118 instructed a KC, in an abortive attempt to threaten us with defamation proceedings, the KC said:

We see no evidence of Property118 and Cotswold Barristers ever carrying out a fact specific analysis before the strategy is recommended. The “strategy” is always set out in the first standardised advice note prepared by Property118, before Cotswold Barristers are engaged, and before any substantive work is undertaken. We have not seen any evidence of any legal analysis of this point subsequently.

Can the company claim a tax deduction for the mortgage interest?

The first letter, from Property118 says it can (see the second tick mark in the excerpt above). But the basis for this is never explained (and, for the reasons we explain around the misdrafted indemnity, in fact the company can’t claim a deduction).

The fact the trust appears to be a settlement further complicates this; naturally none of the advice from Property118/Cotswold Barristers considers that.

Is it correct that the “growth shares” issued by the company have a valuation of zero?

Property118’s structure involves issuing “growth shares” which carry an entitlement to all future capital gains of the company. The claim is that they initially have a valuation of zero. That is highly questionable. However neither Property118 nor Cotswold Barristers appears to undertake any valuation exercise to justify the claim.

Does the “director loan” structure work?

It’s the director loan which creates the “ability to draw down capital tax free”. It’s achieved using this astonishing structure – a bridge loan that’s put in place for a few hours immediately prior to incorporation, and moves between two escrow accounts without ever being available to the landlord or their business.

In our view the structure prevents incorporation relief applying, with an additional risk that “loan repayments” become taxable. Cotswold Barristers provide no advice at all on the effect of the structure.

Does anti-avoidance legislation apply?

There are a plethora of anti-avoidance rules that are engaged if, as here, a transaction has a “main purpose” or “main benefit” of obtaining a tax advantage: DOTAS, rules denying interest deductibility, GAAR, settlor-interested trust rules etc. Advisers would usually cover these issues even on simple and innocuous structures. We would also usually expect advisers to cover the Ramsay common law anti-avoidance principle.

However, there is no evidence that either Property118 or Cotswold Barristers have considered or advised on any of these issues. As we note above, Mark Smith’s DOTAS article demonstrated a complete lack of understanding of the rules.24It is also notable that Mark Alexander, who runs Property118, appeared completely unaware of Ramsay, thinking a reference to “WT Ramsay” was a mistaken reference to the recent Upper Tier Tribunal Elizabeth Moyne Ramsay case

To be clear, most clients don’t want or need detailed technical advice. However in our view a reasonable tax lawyer should always provide advice as to the tax consequences of a transaction, particularly when it is an unusual one – even if the advice is highly summarised.

We cannot explain the templated advice and lack of advice on key points. It is possible that there is detailed advice which all of our sources either missed or have mislaid. However, if that is wrong, it raises serious questions as to Mark Smith’s actions – the clients certainly believe they are receiving specific advice from a barrister.

So why aren’t they?

Inappropriate attitude to risk

Good tax advice on complex structures always contains a discussion of risks, both under current law and the risk of change of law. In 2017, the Court of Appeal found an adviser negligent for failing to warn of the risk of a structure, even when the advice was not itself negligent. This had the obvious effect of making risk warnings more common, even when tax advisers are looking at straightforward arrangements.

There are no risk warnings in the Cotswold Barristers (or Property118) advice we have seen.

Indeed, the claim is made that their clients are “shielded from financial risk” because the barristers carry £10m of professional indemnity insurance per client.

This is highly misleading.

To access professional indemnity insurance, clients have to successfully sue the barrister for negligence, and that is not straightforward.

David Turner KC, an insurance specialist, was doubtful that Cotwold Barristers really carry £10m of insurance “per client”. His view was that the standard Bar Mutual policy’s “aggregation” clause meant that it would be £10m per “originating cause”. If the Property118 structure is defective then that would likely be one “originating cause”, and the £10m would therefore be shared by all 1000+ clients. Cotswold Barristers subsequently confirmed that David Turner was correct (but tried to stop him publishing that confirmation).

The failure to warn clients of risks may itself amount to negligence. The false claims made about the insurance appear to make the situation more serious.

Who are Cotswold Barristers?

Barristers chambers usually list their members – the members being the whole point of the chambers. Cotswold Barristers is unusual in not doing this. It did at one point – and included as part of its team a fake barrister with a dubious past who was jailed for conning a dying woman out of her life savings.25There is no suggestion that Cotswold Barristers was aware of his actions, but Cotswold Barristers does appear to have been responsible for listing him as part of its team.

Cotswold Barristers’ correspondence address and registered office is an industrial unit at Cotswold airport.

The only barrister named in the advice sent to clients, or on the Cotswold Barristers website, is Mark Smith26Not to be confused with Mark Smith, the respected extradition barrister.. Smith is a generalist whose practice ranges from general business law, to copyright, to tax, to criminal defence work, to private prosecutions (including one where he was suspended by a month by the Bar Standards Board for acting negligently and “failing to act with reasonable competence“). His profiles in 2017 and 2020 didn’t include tax in his areas of practice.

Tax barristers usually train and practice in a “tax set” – a chambers entirely or partly dedicated to tax law. Mr Smith did not; indeed, in a discussion on LinkedIn, it was not clear Mr Smith had heard the term “tax set”.

A core duty of barristers is maintaining their independence. Cotswold Barristers Ltd is a director of Property118.

Conclusion

On the basis of the documents we have reviewed, it seems plausible that the Property118 scheme fails because of poor implementation, leading to a failure to achieve the intended tax benefits, and significant additional up-front tax. It also seems plausible that Mark Smith and Cotswold Barristers have been serially negligent.

Thanks to SH and D for their trust expertise, and J and K for their invaluable input and review. Thanks to David Turner KC for investigating the insurance position. Thanks to C for input on the indemnity/interest points. Thanks to F and N for technical accounting input. Thanks to G and S for helping locate Property118 advice and documentation, and for their assistance with the technical analysis. Thanks, as ever, to S2 for specialist SDLT input and reviewing after publication. Thanks to James Robertson for the s284 point. Finally, thanks to Ray McCann for his original comments on the DOTAS analysis, and to Patrick Way KC for his insights on a Bell Howley Perrotton LLP podcast (recorded 8 November 2023; not yet broadcast).

-

1It’s relevant to note that a court or tribunal would not necessarily approach the Property118 structure point by point, in the way that we have analysed in our reports. In a recent podcast discussion on the Property118 structure, Patrick Way KC made the important point that, when a structure looks like tax avoidance, the modern judicial approach is to find against it on principled grounds and not undertake the full technical analysis.

-

2This is the only meaning we can see “vest absolutely and immediately in the Trustees” can have. It is unclear what “in accordance with their various legal and equitable interests” means, given that a trustee obviously has no equitable interest. Possibly it means that the Trustee takes the same % beneficial ownership as they had before the trust was originally declared.

We have considered whether this could simply be a typo, and 2.4 should be read as meaning that the Property vests “absolutely and immediately in the Beneficiary“, but we don’t think that can be right. First, the property has already vested in the Beneficiary, so it doesn’t make sense to say that the Trustee can by notice vest it again. Second, it would be odd for the Trustee by notice to trigger its own loss of legal title. Third, the “or” clause at the end of the paragraph deals with the scenario where the Beneficiary has called for legal title; why would there be two subclauses doing the same thing? We therefore don’t believe the wording can be ignored, no matter how inconvenient it may be. The drafting is clearly a mistake from a tax perspective, but that doesn’t mean it can be ignored – there is, after all, commercial utility to enabling the landlord to unwind the structure at any time. It might be possible to make an application to the court for rectification on the basis there was a mistake of law and/or mistake of tax law, but this would be far from straightforward. -

3James Robertson added another point we missed in our initial analysis: the potential for an up-front market value CGT charge under s284 TCGA (sale with a right to reconveyance). The interaction between the different provisions would require considerable thought, but likely there would be only one up-front market value CGT charge, whether under the settlement rules, s284 or on the grant of an option.

-

4This is the view of our team (including a KC specialising in the tax treatment of trusts), but should not be regarded as the final word; a definitive analysis would require consideration of the full facts and circumstances, and it would be wrong at this stage to preclude the other two possibilities.

-

5The grant of an option is immediately subject to CGT. As the parties are connected, the consideration will be deemed to be market value, and the market value of an option to acquire the properties at any time for free will be (broadly speaking) the current market value of the properties. The transfer of property to a settlement triggers an immediate CGT charge at current market value.

-

6Including the settlor interested trust rules effectively reversing any potential income tax benefit, and a 6% inheritance tax charge every ten years. Possibly also a 20% entry charge, and the application of the gifts with reservation of benefit rules, although this would need a careful analysis which we have not undertaken. If a settlement arises then it would have to be registered with the Trust Registration Service. Mark Smith takes the view that the intended “bare trust” is not registrable – we are not sure that is correct, but it’s irrelevant if in fact the trust is not bare.

-

7This would, however, need careful thought. It would be very inadvisable and perhaps improper to simply proceed on this basis without detailed and case-specific legal analysis.

-

8i.e. because our previous analysis was on the assumption that Property118 correctly implemented their structure. We also note that, when Property118 briefly hired a tax KC in an attempt to threaten us with a libel suit, it seems likely that she did not review the transaction documents, as she said specifically that her views were on the basis that the structure was “properly implemented” – see paragraph 13 here. The KC did add that she had reviewed client files, but we expect this was advice and correspondence with HMRC, not transaction documentation – if the KC had reviewed transaction documentation then we believe her opinion would have been very different.

-

9In the interests of simplicity, this analysis in this section of our report ignores the first drafting error – the fact the trust is probably a settlement and not a bare trust. In reality the interaction of the two issues would need to be considered, and that is not at all straightforward.

-

10And is likely entirely unaware of the transaction.

-

11Our team had different views. Some of us believe the clause could be read broadly, given that the trust anticipates the existence of the mortgages. Others don’t agree, because the mortgage payments are not “chargeable on the Property” (rather, they are personal obligations of the landlord), and the mortgage payments do not “arise out of the settlement” (also, what does “payable to them” mean? The word “to” looks like a typo, but it’s included in all the versions of this document we’ve seen).

-

12Usually lawyers never put operative provisions into recitals, but where a contract is silent on a point, an operative provision in the recitals will be effective – see the old case of Aspdin v Austin (1844).

-

13The fact the indemnity payments are not termed “interest” in the documents is irrelevant (see the Re Euro Hotel case) – economically they are interest on the principal amount created by the sale contract and therefore are interest for tax purposes (see Bennet v Ogston). Probably they would not be interest even if there was no principal amount – our original view (prior to having reviewed the document set) was that they would be either taxable annual payments or capital payments (i.e. sale consideration).

-

14This is not the case for a normal incorporation, which achieves other objectives: e.g. segregating liability and obtaining commercial financing – however the Property118 structure does not achieve this

-

15And Smith did not then consider any of the many anti-avoidance rules which will be engaged if there is a tax main benefit or tax main purpose

-

16Smith misses that there are several ways in which there can be no promoter: (1) in-house schemes, clearly not relevant; (2) the promoter is outside the UK, not relevant; and (3) no promoter. If Smith was right that Property118 wasn’t a promoter then this would be the third scenario, not the first. He makes a bad mistake and is then badly wrong on the consequences of his mistake.

-

17And DOTAS looks at the “proposed arrangements”, and therefore the fact that Smith accidentally omits the indemnity is no defence

-

18The confidentiality hallmark would also likely apply, given that Property118 refused to disclose details of their scheme on the basis that it is “valuable intellectual property”

-

19A “compliance check” is not a tax term, but we are assuming these were “aspect enquiries” and not full enquiries.

-

20As an aside, Smith tends to refer almost exclusively to HMRC guidance, and in this case the first guidance appearing on Google doesn’t mention the subsection 17 rule (probably because the guidance pre-dates the legislation). That is speculation; however it is notable that reliance on this out-of-date guidance was one of Less Tax for Landlords’ big mistakes.

-

21The reference to HMRC manuals is curious – advisers should be advising on the basis of the law, particularly when a transaction is tax-motivated (as HMRC guidance cannot be relied upon in such circumstances).

-

22Which is why we are confident we will not reveal our sources by publishing extracts from Property118 advice and documentation

-

23Note in passing that “a discretionary trust controlled by you” is not how discretionary trusts can work if they are to be respected for inheritance tax purposes.

-

24It is also notable that Mark Alexander, who runs Property118, appeared completely unaware of Ramsay, thinking a reference to “WT Ramsay” was a mistaken reference to the recent Upper Tier Tribunal Elizabeth Moyne Ramsay case

-

25There is no suggestion that Cotswold Barristers was aware of his actions, but Cotswold Barristers does appear to have been responsible for listing him as part of its team.

-

26Not to be confused with Mark Smith, the respected extradition barrister.

21 responses to “What’s worse than a tax avoidance scheme? A badly implemented tax avoidance scheme.”

I see from the CIOT page here https://www.tax.org.uk/hmrc-one-to-many-letter-capital-gains-tax-incorporation-relief-property-businesses that HMRC will be writing “one to many” letters to some individuals who incorporated their property businesses into a limited company, but reported no capital gains tax liability on the basis that incorporation tax relief applies. They seem to be starting with the 2017/18 tax year.

One of the points that the standard form of letter says to check is: “that your calculation of the incorporation relief available to you didn’t include any other type of consideration apart from shares received in exchange for the property business – for example, a sum credited to director’s loan account.”

I suspect the expert tax advice from Cotswold Barristers will be that the only other consideration was the assumption of “business liabilities” within ESC D32, so nothing to report.

Hello,

Yes, the penny has finally dropped! If the arrangement of the declaration of trust is NOT intended to be transitory and you have no plan in place for the refinancing and indeed no intention of doing so then you are trying to obtain a tax advantage which is not available to you via a usual/regular path to incorporation.

Shocking to see how P118 recruits their “tax advisors”.

https://www.propertytribes.com/less-tax-4-lls-vs-property-118-structures-t-127642288-lastpost-user-404750.html

I’m really proud of you having the courage to post articles around a time when solicitors are SLAPP happy. Stay true and stay amazing Dan. I’m a massive fan of your work and if everyone in society was like you then life would be as it should be, accountable, honourable and uncomplicated

I agree that it would be good to resolve the issues now.

As this scheme is fairly new (oldest is 2020?) I suggest that HMRC offer a “wipe clean” approach to any client who has done this who comes forward by some short deadline – i.e. that the contracts are regarded as void, so tax is recalculated as if they never existed (which may mean paying extra tax for the last couple of years with interest but no penalties).

Clients are then out of pocket by the fees they paid to P118, plus fees to proper tax advisers as they deal with HMRC, which seems a roughly appropriate level of punishment, learn not to believe such things again, and pass on the message which discourages future such bad actions.

That removes the hassle of untying the legal mess of trusts created and issues with mortgage lenders which really doesn’t would not add any value to the world.

Mark Smith gets struck off.

But there remains the question of the c£50M that the Marks have received, less some costs to innocent staff (and perhaps to some less innocent ones too?)

By moral right, that should go to the government.

The DOTAS penalty rules say £5k per client as well as the £1M, but that’s only another £5M.

Theoretically I like the idea that the clients’ settlement with HMRC should involve their assigning their claim for loss (the fees) to HMRC but that would require some legal innovation (they do pay a penalty so suffer a loss, but then get it refunded??)

It seems that Bernie Ecclestone has introduced Section 153a of German Code for Criminal Procedure to the UK this year, so there is a path to follow?

Do the insurers deserve to take a hit for not monitoring their policyholder, or would that introduce more red tape on bona fide practitioners?

Hi Dan. In relation to their defective advice on mixed member partnerships, you have said that the failure to consider s850C(17) ITTOIA was “incompetent”. That is certainly the case. However, I believe, based on my experience of dealing with CB, that you are being too kind to them. About 7 years ago (I cannot be more precise), when I was still in practice (I am now retired), a client brought to me some advice they had received from Mark Smith recommending the set up a mixed member partnership in exactly the way set out in your article, with profits being routed to the corporate partner in return for alleged services provided in manging the properties. I pointed out that s850C(17) meant that this would not work. After a bit of a delay Mark Smith responded by saying that he agreed with this and they would amend their advice accordingly. I never saw the amended advice. I remember being flabbergasted that they were advising on a structure that simply did not work. At the time the mixed member partnership rules had been in place for at least a couple of years. There really was no excuse. However, it now appears, from what you have said, that they have been continuing to sell this structure. This is not just incompetence since, given the exchange that I had with them all those years ago, they could be in no doubt that it didn’t work. This goes beyond incompetence. Choose your own word to describe it. i know what I think.

As an aside, on the same case Mark Smith was also suggesting that they change the partnership profit sharing ratios each year in order to maximise tax “efficiency”. He was completely unaware of the fact that para 14 sch 15 FA03 would mean that, each time the profit sharing ratios were tweaked, an SDLT charge would arise. He attempted to make the lame excuse that it was likely that any such charge would be covered by the nil rate band. It did not take much effort to show that, on a portfolio of the size in question, it would only take a small adjustment to the profit shares to trigger a real tax charge. And this would arise every year! “Incompetence” does not do it justice!

Thanks, Robert. I would still put this down to disorganisation/lack of competence rather than anything more serious.

The multiple SDLT point is indeed a big problem. It was one of the many issues with the Less Tax for Landlords’ structure – we talked about it here.

You’re a generous man Dan! But perhaps you’re right.

Will Mark Smith follow through on his promise to put his clients back into the position they would be in but for his negligent acts? I hope he has deep pockets or maybe some substantially incorporated rental properties of his own.

Excellent as ever. As someone who never practiced in this area, there would have been some danger signals that I would have missed but plenty more that would have prompted me to advise getting good counsel’s opinion even if I was not sure why in every instance. My question is:

1) The agreement is contingent on using their counsel. That may be duress if…

2) The client does not have sight of the full agreement on which to get external advice.

Does the work flow allow for either of the above?

More good points highlighted (or should I say Spotlighted?) in this article.

P118 and CB are joined at the hip so it’s bizarre for P118 to suggest they aren’t a ‘promoter’ of a scheme. Their own words in one of the paragraphs Dan posted above states the words ‘Joint Venture’ when referencing P118 and CB.

The outright delusion in the comments section on the P118 website continues. It is clearly a case of “I WANT this to be safe and above board so it IS safe and above board”.

It won’t take HMRC long to check back over a few SA tax returns to find that templated script P118 ‘advise’ their clients to put in the CGT box. A basic algorithm will spot how many people have been talked into this blatant avoidance scheme just by scanning tax returns, and I fear the outcome will be financially painful for scheme users.

The two Marks will probably stop posting nonsense articles on their website now because they are literally providing the ammunition for HMRC to fire at them each time they do. I also suspect some ‘chair shuffling’ might be going on at CB and P118 soon to avoid incoming claims that their insurers will/won’t be paying out IF it turns out negligence is at play.

Maybe they could ask someone for advice to transfer their Barristers’ Chambers into a new company that negates the requirement to honour previous client advice in exchange for shares in the new company that are valued at ZERO?

I would not be sleeping soundly if I was one of their ‘advised’ clients. In the words of Gorgeous George, “This will get messy”.

Good work Dan.

As the trust does not seem to be a bare trust and the option to acquire the property would seem to have some value, would there be a chargeable lifetime transfer for IHT purposes on the individual? Either because the individual has given value away to the trust or because the close company has (s94 IHTA).

It’s a great question and I confess we haven’t spent time thinking about it. Not easy given the company is giving value (but in a hard-to-understand way)

I think there is a strong argument that the close company transfers of value provisions apply, or that HMRC could argue that there has been a transfer of value to a person that is not an individual, so that it is a RPT and has an IHT entry charge, although CGT holdover under s 260 may apply to mitigate CGT. That still means a 20% liability on the MV of the properties, rather than a 28% liability on the property gains.

Has anyone heard when the “official” verdict on all this will be announced (publication of HMRC Spotlight?)

HMRC Spotlights are unusual – plenty of schemes attacked by HMRC never featured in a Spotlight. The “official” HMRC verdict more often comes in a series of individual enquiries (none of which are public) and the real verdict, perhaps, in a tribunal hearing years later.

In the meantime, taxpayers have to make their own mind up based on advice from qualified professionals.

Quite right of course although I did wonder why the mixed LLP structure got Spotlighted and this didn’t. Maybe we have a while to go yet of Mr Alexander continuing to insist that you’re unreasonably seeking to ruin his perfectly good business.

The LT4L “hybrid partnership” structure seems a good deal worse because claims are made (e.g. BPR, base cost uplift, mixed partnership rules not applying) which seem to have no legal basis at all.

There is this, per CIOT website, this afternoon (10 Nov 23): https://www.tax.org.uk/hmrc-one-to-many-letters-concerning-spotlight-63-llp-property-tax-planning

thanks – yes, writing about that on Monday.