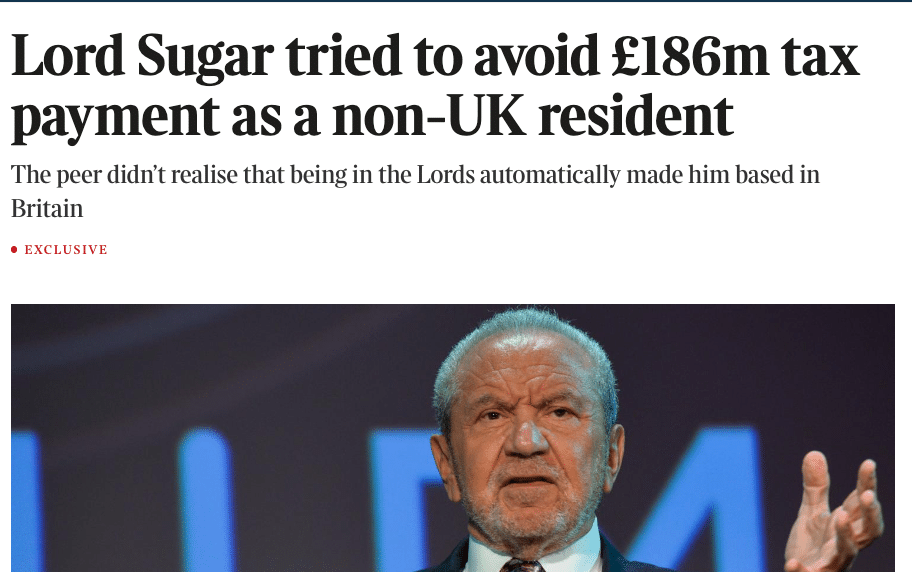

The Sunday Times has a remarkable story that Lord Sugar tried to avoid tax by leaving the UK for Australia. The idea was that he’d cease to be UK resident, and so would escape £186m of tax on some very large UK dividends.

Somehow neither Sugar, his team, or his advisers ever thought to do a simple Google search:

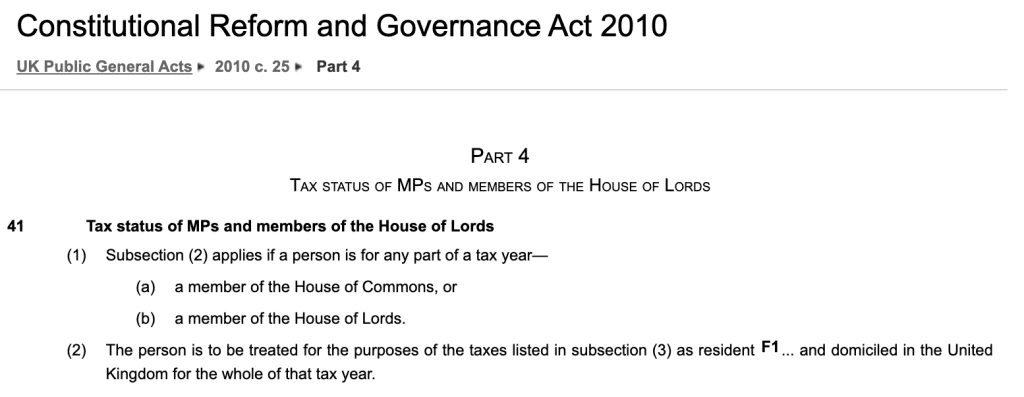

Which would have led them to this:

So the answer as to why Lord Sugar failed to become a tax exile is easy. The CRGA means that, as a member of the House of Lords, he would have been UK tax resident whether he lived in Basingstoke, Sydney or on the Moon.

It’s a fun story (not for Alan Sugar, and not for his advisers, who the Sunday Times says he’s now suing 1Most professional negligence claims settle well before reaching a court, but on on the face of it this looks like a slam-dunk. However, we don’t know all the circumstances, what questions were asked, and whether advice was preliminary or definitive. The advisers may also be able to point to limitations of liability in their standard terms – accountants often limit liability to £1m (or thereabouts), even on very large transactions, and whether these limitations apply in a particular case is often a difficult question. Sugar would also have to show that, if he had been properly advised, he would have resigned his seat in the Lords, and then remained non-UK resident for five years – and demonstrating these kinds of counter-factual questions isn’t always easy). But there’s a bigger question: why does the UK make it so easy to become a tax exile?

Tax exiles

There is a longstanding debate in some circles on whether, and to what extent, people in general move in response to high taxes (often based around studies of US state taxes). I confess this always seems a little unreal to me. Just to start: Sir Jim Ratcliffe (Ineos),2The original version of this article included Toto Wolff, the motorsport executive. I don’t think he really belongs in it – he left the UK for tax security reasons, but given he wasn’t born here, and didn’t make his money here, he shouldn’t be on the list. Lewis Hamilton (racing), Tina Green, the Barclay brothers, Richard Branson, David and Simon Reuben (property), John Hargreaves (Matalan), Terry Smith (fund manager), Steve Morgan (housebuilder Redrow), David Rowland (financier), Joe Lewis (Tavistock Group), Anthony Buckingham (Heritage Oil), David Ross (Carphone Warehouse, Mark Dixon (IWG)3Dixon’s Wikipedia article says he voluntarily pays tax in the UK. I doubt it.. There are many more. Some estimate that one in seven British billionaires now live in tax havens; others one in three.

Looking at the Sunday Times “Rich List”, I’m struck by how few of those listed still live in the UK. Most of these people left the UK for a very specific reason. They built up a successful business, and were about to make a large amount of money from that business (perhaps by selling it; perhaps through a large dividend). They left the UK, sold the business (or received the dividend) and made a large tax-free gain/profit. They became a tax exile.

How tax exile works

There isn’t a loophole or trick – its just that, like almost all4“almost all” meaning “everyone except the US”. There’s a reason the US is an outlier here. other countries, the UK only taxes people who live here – who are “UK tax resident”.5There used to be a huge loophole – you could leave the UK on 4 April 2020, become non-resident for the 2020/21 tax year and receive your massive gain tax-free, then fly back into Heathrow on 5 April 2022. That no longer works. There’s a special rule to tax “temporary non-residents”. If you leave the UK but become UK resident again within five years, any capital gains you made during the five years are immediately taxable.

- A Frenchman in Paris won’t be subject to UK tax on dividends from UK companies. If he moves to the UK, he’ll become UK tax resident, and be subject to tax on that income6But not his unremitted French income/gains, because he will be a “non-dom“..

- A Brit living in London is of course UK resident, and subject to UK tax on her UK dividends. But if she leaves the UK, she’ll no longer be taxed on those dividends.

This is sensible and uncontroversial. The UK has no business taxing people who don’t live here.

It becomes more controversial if that Brit has spent her life in the UK growing a business, and is (say) sitting on an offer from someone to buy the business for £50m. The UK has, by international standards, a pretty low rate of tax on capital gains – 20%. But if she leaves the UK and moves to a country that doesn’t tax capital gains then she’ll escape all tax on the £50m. That used to mean going to a tedious tax haven like Monaco, but there are an increasing list of non-tax havens that don’t tax recent immigrants on their foreign gains – e.g. Australia, Portugal7Correction: Portugal would tax gains, but not dividends. So obvious ploy is to keep hold of the shares, but extract all the value via a dividend. Which amounts to the same thing, subject to a bit of messing around with distributable reserves and Israel.8And the UK is in a similar category in the reverse case – the UK non-dom rules means that a foreigner coming to the UK is not taxed on their foreign gains, unless they remit them to the UK. That is less generous than Australia, Portugal and Israel, where the gains are exempt even if brought into the country.

Could we stop tax exiles?

Absolutely. Many countries try to stop tax exiles, or limit the tax they avoid, with “exit taxes”.

Typically how this works is that, if you leave the country, the tax rules deem you to sell your assets now, and if there’s a gain then you pay tax immediately (not when you later come to sell). Sometimes you can defer the tax until a future point when you actually sell the assets or receive a dividend.9Often you have to provide some form of guarantee so you can’t just promise you’ll pay in future, and then scarper And if your new home taxes your eventual sale, then your original country will normally credit that tax against your exit tax. Of course, it works out more complicated than this in practice because it’s tax, but the basic principle is both straightforward and commonly implemented in other countries. For example:

- France has a 30% exit tax on unrealised capital gains, with a potentially permanent deferment if you’re moving elsewhere in the EU, or to a country with an appropriate tax treaty with France.

- Germany has a 30% exit tax on unrealised capital gains. If you’re moving elsewhere in the EU you used to get a deferral; from the start of 2022 you instead have to pay in instalments over seven years.

- Australia has an exit tax on capital gains tax – unrealised gains are taxed at your normal income tax rate for that year. There is a complicated option to defer.

- The US has an exit tax for people leaving the US tax system by either renouncing their citizenship, or giving up a long-term green card. Unrealised gains in their assets, including their home, become subject to capital gains tax at the usual rate. No deferral.

- Canada is of course much nicer than the US. Unrealised gains are taxed, but there’s a deferral option, and your home isn’t taxed at all.

Why didn’t the UK create an exit tax years ago? We didn’t have capital gains tax at all until 1965, and it was easy to avoid until the 90s. After that, we ran into a big problem with EU law, which greatly complicates exit taxes – in particular by requiring an unconditional interest-free deferral of exit tax until an actual disposal of the assets. That enables a massive loophole for taxpayers to leave a country, and then extract value through dividends, rather than a sale. Germany is attempting to ignore this, and I expect that will not end well.

So one new freedom the UK has post-Brexit is the ability to impose our own exit tax that has no leaks, and which the CJEU can’t stop. 10Some tax nerds will worry that the UK’s many double tax treaties make this hard, because we often give up our right to tax non-residents on their capital gain. To which I say: easy, deem the tax to apply on the last day they were UK resident, so the treaty isn’t relevant. And then expressly override the treaty anyway, just to be safe. After all, treaties are supposed to be used to prevent double taxation, not to avoid taxation altogether.

(The UK has some exit taxes already. Companies migrating from the UK pay an exit tax. Stock options are subject to a mini-exit tax. Some trusts are subject to an exit tax. I’m sure there are a few more. But we currently have no general exit tax on individuals).

Should we stop tax exiles?

There are, inevitably, two opposing views:

One is that everyone is free to live where they wish, and if they move somewhere with lower tax, that’s up to them. No Government has a right to tax people for leaving. The knowledge that high-earning individuals can skip the jurisdiction, imposes a useful pressure on governments not to raise tax too high. It’s a useful form of tax competition.

The other view is that if you spend years in the UK building up your business, it’s only right that the UK should have the right to tax the gain you make on selling that business. More pragmatically, it seems counterproductive for the tax system to incentivise people to leave. This kind of “tax competition” is an undesirable infringement on countries’ right to raise taxes, particularly on the wealthy.

So what should we do?

I’m not sure. I’d want to see more evidence and analysis of the real-world impact of an exit tax. A poorly designed tax could put people off coming to the UK, or even accelerate departures (i.e. by causing entrepreneurs to flee to Monaco as soon as things start going well, rather than waiting until just before their big payday). And even just talking about an exit tax is dangerous, because it could prompt tax exiles to skedaddle immediately.11It follows that any exit tax would have to be announced suddenly and with great fanfare, and made retrospective to the date of the announcement. This would be controversial, but introducing a non-retrospective exit tax would be *massively damaging* – there would be a mass exodus of the super-wealthy Any exit tax would also need to be carefully designed to have no impact on people genuinely leaving the UK for other “normal” countries in which they’ll be fully taxed on their future gains – it should be targeted specifically at those who leave for tax havens (but targeting specific tax results, not specific countries).

In the interests of fairness, if we’re introducing new rules for capital gains when people leave the UK, we should also look again at the capital gain rules when you arrive in the UK. Right now if (for example), you build a business worth £100m from nothing, come to the UK and sell your business the next day, the UK will tax you on all £100m of gain. Even though little or none of that gain was made in the UK. That feels unfair; and there is anecdotal evidence that it deters some entrepreneurs from moving here. So we should have an entry adjustment – “rebasing” the asset to its market value at the date you arrive in the UK.

So there is a case to be made for changing the law in both directions, and establishing a principle that the UK taxes gains made when you were in the UK, and doesn’t tax gains made when you weren’t. But any change needs to be implemented cautiously and with great care.

-

1Most professional negligence claims settle well before reaching a court, but on on the face of it this looks like a slam-dunk. However, we don’t know all the circumstances, what questions were asked, and whether advice was preliminary or definitive. The advisers may also be able to point to limitations of liability in their standard terms – accountants often limit liability to £1m (or thereabouts), even on very large transactions, and whether these limitations apply in a particular case is often a difficult question. Sugar would also have to show that, if he had been properly advised, he would have resigned his seat in the Lords, and then remained non-UK resident for five years – and demonstrating these kinds of counter-factual questions isn’t always easy

-

2The original version of this article included Toto Wolff, the motorsport executive. I don’t think he really belongs in it – he left the UK for

taxsecurity reasons, but given he wasn’t born here, and didn’t make his money here, he shouldn’t be on the list. -

3Dixon’s Wikipedia article says he voluntarily pays tax in the UK. I doubt it.

-

4“almost all” meaning “everyone except the US”. There’s a reason the US is an outlier here.

-

5There used to be a huge loophole – you could leave the UK on 4 April 2020, become non-resident for the 2020/21 tax year and receive your massive gain tax-free, then fly back into Heathrow on 5 April 2022. That no longer works. There’s a special rule to tax “temporary non-residents”. If you leave the UK but become UK resident again within five years, any capital gains you made during the five years are immediately taxable.

-

6But not his unremitted French income/gains, because he will be a “non-dom“.

-

7Correction: Portugal would tax gains, but not dividends. So obvious ploy is to keep hold of the shares, but extract all the value via a dividend. Which amounts to the same thing, subject to a bit of messing around with distributable reserves

-

8And the UK is in a similar category in the reverse case – the UK non-dom rules means that a foreigner coming to the UK is not taxed on their foreign gains, unless they remit them to the UK. That is less generous than Australia, Portugal and Israel, where the gains are exempt even if brought into the country.

-

9Often you have to provide some form of guarantee so you can’t just promise you’ll pay in future, and then scarper

-

10Some tax nerds will worry that the UK’s many double tax treaties make this hard, because we often give up our right to tax non-residents on their capital gain. To which I say: easy, deem the tax to apply on the last day they were UK resident, so the treaty isn’t relevant. And then expressly override the treaty anyway, just to be safe. After all, treaties are supposed to be used to prevent double taxation, not to avoid taxation altogether.

-

11It follows that any exit tax would have to be announced suddenly and with great fanfare, and made retrospective to the date of the announcement. This would be controversial, but introducing a non-retrospective exit tax would be *massively damaging* – there would be a mass exodus of the super-wealthy

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – just so people can clearly see the more technical comments. I will also delete comments which are political in nature.

17 responses to “Why Alan Sugar failed to become a tax exile, and why so many others succeed.”

A rebasing of gains on becoming UK resident would be very popular with returning expats who chose, historically to invest in property.

The Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill was debated in the House of Lords in March & April 2010.

Lord Sugar was appointed to the House of Lords in 2009.

Perhaps if he had attended on those dates, or at least kept up with the legislative schedule, he would have been aware of the rule.

Lord Sugar would have had to become non-resident for at least five UK tax years to avoid income tax arising on the dividend, as dividends from close companies are caught by the temporary non-resident rules.

The Times mentions Australia as his new location. Australia has no inheritance tax. Lord Sugar is 76.

That’s a great point! Although he may be mostly exempt from IHT anyway, under business property relief…

I believe a large chunk of his fortune is held in non-residential investment property which would not qualify for BPR.

https://www.amsprop.com/portfolio.html

Acquiring a domicile of choice in Australia and losing his UK domicile of origin would however be difficult for a former member of the House of Lords. He would have to renounce his allegiance to King Charles III and swear fealty to Ned Kelly or Skippy The Bush Kangaroo.

When the original article in the FT was published (“Alan Sugar faces call to clarify UK tax status” – 20 July 2022) I saw this quote from his spokesman: “We are instructed to tell you that Lord Sugar is a UK taxpayer and will remain so. We have not asked you to write about our client, and as such we are not prepared to act as your editor. Please do not ask any further questions, as they will not be answered.” and thought it a bit rude and so I looked at the legislation (and found s41). I then spent a bit of time seeing whether taking a leave of absence changes that but couldn’t see that it did.

I did wonder how he was going to deal with the temporary non-residence rules and so I looked at the accounts for Amshold Limited for the year ended 30 June 2021 and this showed a £31m consolidated profit after tax and a dividend of £390m. The company-only statement of changes in equity shows that on 27 March 2019 the company randomly issued £545 million of shares and then on 8 April 2021 reduced this by £75m, with that amount going to distributable reserves. Another £465 million was transferred from share capital to reserves in September 2021. So I’d assumed that this non-resident process was due to happen for the 2021/22 tax year (but I can’t be certain as the date that the £390m dividend paid wasn’t disclosed). That date also ties in with the income tax being due on 31 January 2023 and so ties in with suggestions that the advisors are being sued at the moment.

So I then looked at s401C ITTOIA 2005 and what “post-departure trade profits” means but I couldn’t see that these were trading profits of Amshold Limited and so I though that he was planning on being away for at least five years. But by this stage I had better things to do and so didn’t try to reconcile the apparent conflict between HoL tax residency rules and what he was trying to do.

The temp non-res loophole closure came in during the late 90s didn’t it? The article suggests it’s very recent

Temporary non-residence for CGT came in in 1998 but it was only introduced for dividends in 2013 (along with the statutory residence test). Still 10 years though, so not terribly recent. It can take more than 5 years to be clear now too. It has to be more than 5 years, but you can include overseas parts of split years. This could be 5 years and a day of actual absence, but it can also mean six whole tax years if you fail split year treatment in both directions.

thank you both!

Lord Sugar became a peer in 2009 and so presumably was one of the only 1,500 or so parliamentarians (members of the House of Commons and House of Lords) who had a vote on the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010, which received Royal assent on 8 April 2010. So he ought to have known what it said about the tax residence of members of the House of Commons and House of Lords. But then, when he was asked in 2009 when he joined the Lords whether he would be taking the Labour Whip, it was clear that he didn’t know what that meant. Downing Street responded that he would indeed be taking the Labour Whip. So he’ll probably be claiming that although the party which was whipping him had introduced the legislation, he knew nothing about it and, if his advisers had told him about it, he’d never have taken the dividend. Humm. And what was his loss?

As far as I can make out, the Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill passed through the Lords in March-April 2010 without any of the readings being formally put to division. There were a couple of divisions on amendments on 7 April, and then “Report and Third Reading agreed without debate”. After a bit of Parliamentary ping pong, but no further divisions, it was passed and given Royal Assent on 8 April. So Sugar really had no opportunity to vote on this Bill, because there were no formal votes in the Lords “on this Bill” (as distinct from a couple of amendment) at all.

I am slightly surprised at the lack of scrutiny, but the Bill was passed quickly on the nod in Gordon Brown’s wash-up period – Parliament was dissolved on 12 April, before the general election in May 2010 that led to the Conservative / Liberal Democrat coalition.

After Alan Sugar became Gordon Brown’s “Enterprise Champion” in June 2009, he became Baron Sugar on 20 July, but voted in the Lords just four times before the May 2010 election, twice on the Coroners and Justice Bill and twice on the Personal Care at Home Bill. There are currently 777 peers entitle to sit in the House of Lords, and many rarely turn up to vote. Sugar has not voted since 2017.

I believe Capital Gains Tax was introduced in 1965, during the Labour Government. Not 1968 as in the article!

An embarrassing error, now fixed. Thank you!

How did The Sunday Times obtain the information about Lord Sugar’s tax affairs? An individual’s tax affairs should be private and confidential so where did the information come from?

Is there a published tax tribunal decision of a case where he challenged HMRC’s assessment? – I couldn’t find one.

Did someone within HMRC leak the details? – unlikely.

Did the information come from the negligence case against the advisers? – Has this been published somewhere?

There’s nothing public about either his taxes or his dispute with the advisers, but plenty of people around Sugar and his advisers will have known about this. I expect that’s where the story comes from – most unlikely it comes from HMRC (not least because HMRC wouldn’t have known he’s suing his advisers).

On the professional negligence aspect, it’s a bit difficult to see what Lord Sugar’s claim is. If the advice given was wrong, then there is probably a breach of duty.

But what is his loss?

If the tax could have been legitimately avoided, then it could be that. Or it could be his reliance losses in paying fees and moving to Australia. Or could he say that he wouldn’t have caused the dividends to be paid out?

I expect he’ll say that, if he’d known the position, he would have given up his seat in the Lords (which is easy to do, and he famously hardly ever turns up).