During the pandemic, Baroness Mone referred a company called PPE Medpro to the Department of Health and Social Care to supply PPE equipment. PPE Medpro was awarded £200m of contracts, in circumstances which are now the subject of litigation and a fraud investigation by the National Crime Agency.

Baroness Mone at the time did not disclose any connection to PPE Medpro, and in 2020 her lawyers denied “any suggestion of an association”. However, new evidence suggests that PPE Medpro’s true ownership was hidden by a company controlled by her husband, Douglas Barrowman. If that was intentional, then criminal offences were committed.

Our full analysis is below, and the Sunday Times is carrying a report on our findings here.

PPE Medpro

PPE Medpro Limited was awarded two contracts to supply PPE equipment in June 2020, worth £200m, having been referred through the “High Priority Lane” by Baroness Mone.

The Department of Health and Social Care has commenced legal action to recover the £122m paid under the second of the two contracts. PPE Medpro is also the subject of an ongoing fraud investigation by the National Crime Agency, and Mone’s actions are the subject of an investigation by the House of Lords Commissioners for Standards’ Office1Currently stayed pending the outcome of the criminal investigation.

Mone has said she is in no way associated with PPE Medpro. Lots of press coverage has been highly sceptical of this.

Who really owns PPE Medpro?

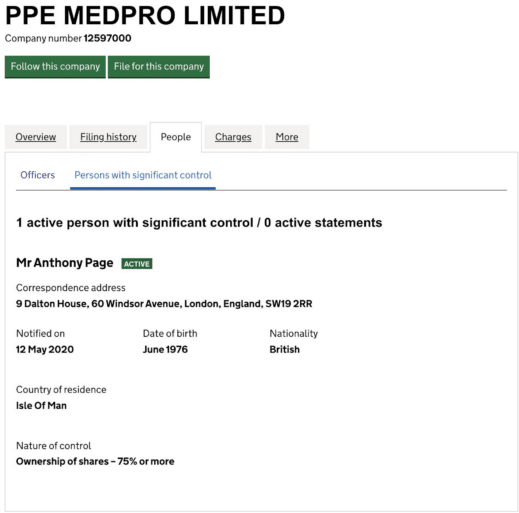

At the time, PPE Medpro’s shares were owned by an Isle of Man resident, Anthony Page.

Sometimes the true owner of a company – the “person with significant control” (PSC) – can be different from the shareholder. For example, if one person owns shares in a company, but there is a formal or informal understanding that they always act on the instructions of another person, then both people should be listed as PSCs.

But the Companies House register showed Mr Page as the sole PSC:

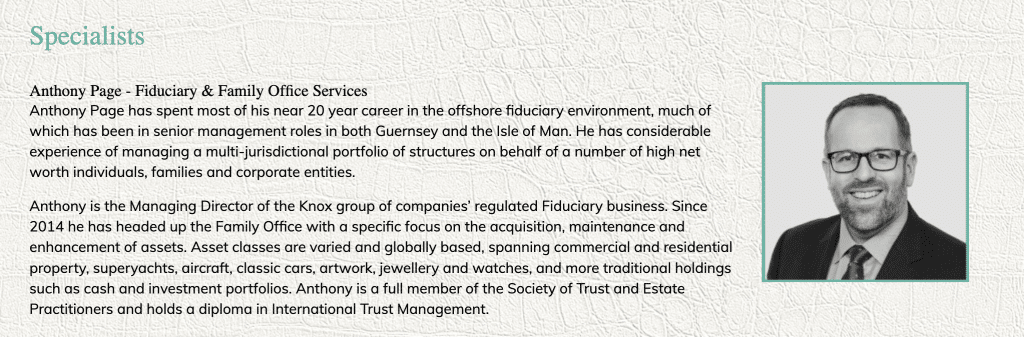

At the same time, Anthony Page was the managing director of the Knox Group.

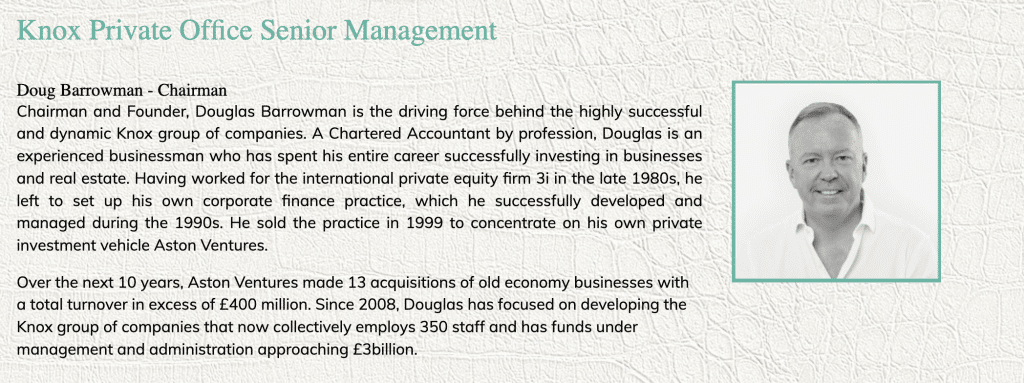

… which was (and is) owned by Mone’s husband, Douglas Barrowman:

Another director of PPE Medpro was Voirrey Coole – who was the director of another Barrowman company.

This suggests three possibilities:

- PPE Medpro was a private venture of Mr Page, and nothing to do with Mr Barrowman.

- Mr Barrowman’s Knox Group was engaged to provide corporate services for an unknown third party, and Mr Page was the shareholder in his capacity as employee of the Knox Group.

- Mr Barrowman was the true owner of PPE Medpro. The Guardian says it has a document listing PPE Medpro and LFI Diagnostics as “entities” of the Barrowman family office (but Tax Policy Associates has not seen that document, and so we cannot independently assess this claim).

How plausible are the three scenarios?

Scenario 1: Mr Page owned PPE Medpro in his own right

New evidence means that this scenario can now be ruled out.

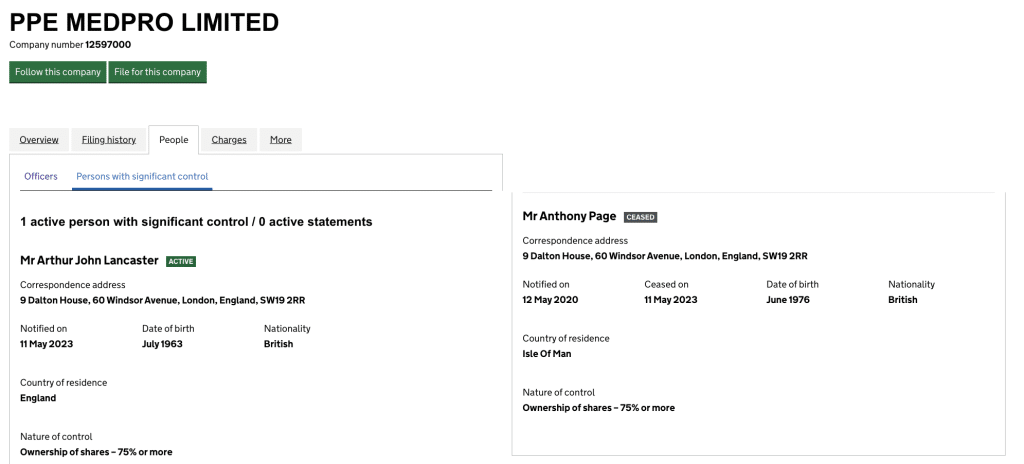

The Sunday Times reported last week that Anthony Page was dismissed from the Knox Group for “gross misconduct”. If Mr Page owned PPE Medpro in his own right then his ownership of PPE Medpro would have been unconnected with his employment by the Knox Group. Page would have remained the PSC of PPE Medpro when the Knox Group fired him.

But instead he was replaced:

Mr Page’s replacement as PSC, Arthur Lancaster, is an accountant who is closely connected to Douglas Barrowman and the Knox Group. Lancaster was recently described by a tax tribunal as “seriously misleading”, “evasive” and “lacking in candor”.

The obvious inference is that Mr Page held the PPE Medpro shares as part of his employment by the Knox Group and, when that employment ceased, he was required to transfer his ownership of those shares. He was not the true owner, and should not have been registered as the sole PSC.

Scenario 2: Mr Page and the Knox Group are acting for some unknown third party

That is what Mone’s people told the FT in 2021:

There are, however, two problems with this explanation.

First, Mr Page and Ms Coole are not acting at all like typical corporate service providers.

Mr Page actually holds the shares in PPE Medpro himself. This is highly unusual. Employees of corporate service providers (CSPs) are often directors for their clients’ companies, but rarely, if ever, shareholders – for the very good reason that this creates unacceptable risks for the client. What if the employee leaves the company? What if they die? Or decide to commit fraud? The best case is that a court order would be required. The worse case is that valuable assets could be lost. We asked one of our contacts, very familiar with the ultra-high net worth world, whether he had ever seen a fiduciary business put a client’s company’s shares in an employee’s own name – he described the suggestion as “insane”.

CSP businesses therefore don’t put shares in their client’s companies in the name of the CSP’s employees. The usual practice is that the CSP business has a nominee company to hold shares when required. For example (to pick two reputable corporate services businesses), Equiom Corporate Services Limited and Intertrust Fiduciary Services Ltd.2We should stress that Intertrust and Equiom are businesses with good reputations and we are listing them as examples of what we consider good practice.

Importantly: the client is a client, and the CSP will do what the client asks. That means that the client and not the CSP is the “person with significant control”.

You can see numerous examples of this if you look at companies where, for example, Intertrust or Equiom, provides one of its employees as director. That employee is never a shareholder, and never listed as the PSC.

Second, Mr Barrowman’s behaviour is hard to explain if in fact the Knox Group was acting as a CSP for some other party

Douglas Barrowman and Baroness Mone are facing serious allegations, and PPE Medpro is being investigated for fraud by the National Crime Agency. It is strongly in his interest to demonstrate that he is in fact not the controller of PPE Medpro. So why wouldn’t Mr Barrowman clear his and his wife’s name by revealing who the true owner of the company is? There is no obligation of confidentiality here – in fact the reverse, because the PSC rules require the true owner to be disclosed.

Hence the suggestion that Mr Page was acting in the ordinary course of his CSP business does not, we believe, fit the facts. It is also an inadequate explanation for those involved because, even if it were correct, the Knox Group will covered-up the identity of the true owner of PPE Medpro, and that has potentially serious legal consequences. We explain this further below.

Scenario 3: Mr Page was acting for Douglas Barrowman

This seems the most plausible scenario, even if we disregard the Guardian report. Mr Page is acting either informally on behalf of Mr Barrowman, as his agent, or as his nominee/trustee – in all these cases, Mr Barrowman should have been disclosed as the PSC.

If that is correct then, again, the Knox Group has covered-up the identity of the true owner of PPE Medpro, with potentially serious legal consequences.

The legal framework

The “people with significant control” rules

Until 2016, Companies House showed who the shareholders of a company were, but stopped there. So if, for example, a company had a “nominee” shareholder, acting at the direction of the real ultimate beneficial owner, then only the nominee would be shown in Company House’s records. There would be no way to find out who the real owner was.

That all changed with the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, putting rules in place requiring companies to identify their “people with significant control” – meaning the actual humans who were able to tell the company what to do.3The legislation starts here, and is fairly easy to read – there’s also useful (statutory) guidance.

The definition of “person with significant control”

The definition is set out in Schedule 1A of the Companies Act 2006, which sets out conditions that will each result in a person being a PSC. In our case, the relevant condition is in paragraph 5:

If, as appears to have happened, the Knox Group had the power to remove Mr Page as shareholder/director of PPE Medpro and replace him with Mr Lancaster, then the Knox Group (and Douglas Barrowman, as the person who controls the Knox Group) had “significant influence or control” over PPE Medpro. Mr Barrowman should have been listed as the PSC. If the Knox Group was acting for some other unknown party then they should also have been listed as a PSC.4With a few exceptions, for example if the unknown party was a consortium in which no person held more than 25% of the company

Either way, there has been a breach.

How the PSC rules work

A company is required to identify and then register its “people with significant control”.

Section 790D of the Companies Act requires a company to take reasonable steps to find out who controls it:

In some cases, a company may not know who its ultimate controller is, and so there are procedures for the directors to notify the immediate shareholder and require them to identify their owners. But in the PPE Medpro case there are no such complexities – Anthony Page and Arthur Lancaster are surely both aware of the circumstances in which they became shareholders of the company, and whose instructions they follow.

A company is then required by section 790M to keep and update a register of its PSCs:

![Duty to keep register

(1)A company to which this Part applies must keep a register of people with significant control over the company.

(2)The required particulars of any individual with significant control over the company who is “registrable” in relation to the company must be entered in the register [F17before the end of the period of 14 days beginning with the day after all the required particulars of that individual are first confirmed].

(3)The company must not enter any of the individual's particulars in the register until they have all been confirmed.

(4)Particulars of any individual with significant control over the company who is “non-registrable” in relation to the company must not be entered in the register.](/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screenshot-2023-08-11-at-13.06.44-1024x236.png)

And section 790VA requires entries in the company’s own PSC register to be notified to the Registrar of Companies (i.e. Companies House):

The criminal offences for directors

There are specific offences for breaches of sections 790D, 790M and 790VA, committed by the company itself, and every director responsible. On conviction, the director faces up to two years in jail and an unlimited fine.

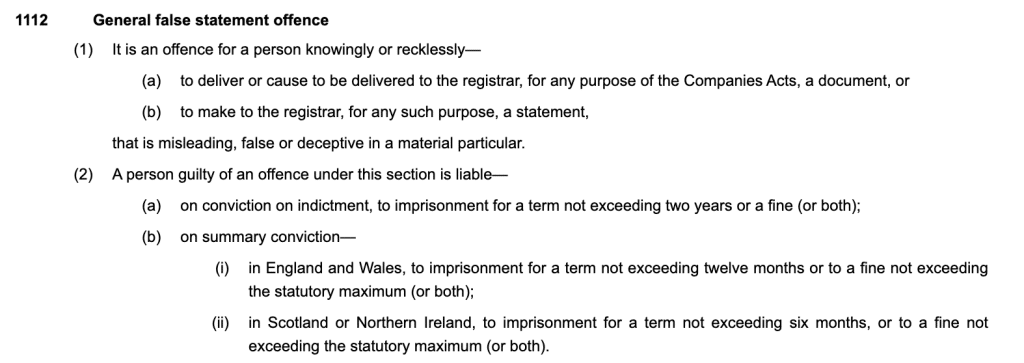

There is also a general Companies Act offence of knowingly or recklessly delivering a false statement or document to Companies House. Again, up to two years in jail and an unlimited fine:

If Messrs Page and Lancaster were responsible for PPE Medpro delivering statements which listed them as the PSCs, when they knew they were acting at the direction of one or more other people, then they potentially committed both offences.

What are the criminal offences applicable to Mr Barrowman?

Mr Barrowman may be a “shadow director” of PPE Medpro – i.e. a person who is not formally a director but who in practice calls the shots. If that is correct, then the specific criminal offences mentioned above will potentially apply to him, in the same way as the registered directors.

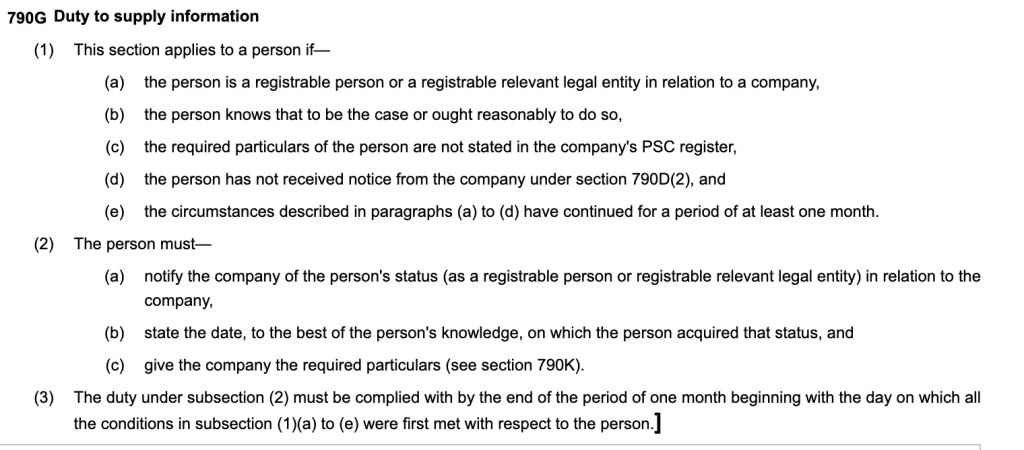

There is also a specific requirement in section 790G that, where someone knows they control a company, but they haven’t received a notice from the company requiring them to provide information, then they have to inform the company:

Failure to comply with section 790G is an offence under paragraph 14 of Schedule 1B of the Companies Act 2006, again punishable with up to two years’ imprisonment, and an unlimited fine.

![14(1)A person commits an offence if the person—

(a)fails to comply with a duty under section 790G or 790H, or

(b)in purported compliance with such a duty—

(i)makes a statement that the person knows to be false in a material particular, or

(ii)recklessly makes a statement that is false in a material particular.

(2)Where the person is a legal entity, an offence is also committed by every officer of the entity who is in default.

(3)A person guilty of an offence under this paragraph is liable—

(a)on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or a fine (or both);

(b)on summary conviction—

(i)in England and Wales, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding twelve months or to a fine (or both);

(ii)in Scotland, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding twelve months or to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (or both);

(iii)in Northern Ireland, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (or both).]](/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screenshot-2023-08-09-at-18.23.57-1024x482.png)

It follows that Douglas Barrowman may have committed a criminal offence if (as is plausible) he was the PSC of PPE Medpro, knew that he wasn’t correctly registered as the PSC, but took no steps to remedy that. Often someone in this position would run the defence that they didn’t understand the rules. For Mr Barrowman that may be difficult, given that he is a sophisticated businessman with years of experience in business, funds and corporate finance, who runs a group of companies that provide technical tax and legal services to private offices. All the more so given that he knows his links with PPE Medpro have been widely reported, and that PPE Medpro is under criminal investigation.

If Knox was acting on behalf of some unknown third party then that action may also constitute a criminal offence.

Will there be a prosecution?

Companies House only prosecutes the most serious offences; in other cases a civil fine is typically levied.

Here there is a possibility that the offence was very serious indeed: i.e. if Mr Barrowman was the true owner of PPE Medpro, and that fact was hidden to enable his wife to recommend the company to the Department of Health and Social Care.

Response from Messrs Barrowman, Page and Lancaster

We wrote to Douglas Barrowman, Anthony Page and Arthur Lancaster on Friday and asked them to comment; we received no reply. That is most unusual for accusations this serious.

We are, as ever, keen to understand if there are any facts we have misunderstood, or any explanation we have missed, and we will update this report as and when we hear anything further.

Next steps

Arthur Lancaster is a member of the Chartered Institute of Taxation and the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales. The CIOT and ICAEW require their members to follow high professional standards. Involvement in an apparent breach of the PSC rules breaches those standards. We have, therefore, written to the Taxation Disciplinary Board and the ICAEW, asking them to investigate Mr Lancaster. Mr Lancaster was previously the subject of a referral to the TDB for the “seriously misleading” evidence he gave to a tax tribunal.

Anthony Page is a member of STEP, the Society of Trust and Estate Practitioners, which has a Code of Professional Standards. Mr Page’s involvement in an apparent breach of the PSC rules breaches that Code, and we have therefore reported him to STEP.

We have provided the information in this report to the Metropolitan Police, and they are currently assessing the information to establish the appropriate investigative body.

Thanks to D and C for their help with the Companies Act and PSC analysis, and G for his insights into ultra-high net worth planning.

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – just so people can clearly see the more technical comments. I will also delete comments which are political in nature, or which are potentially legally problematic.

-

1Currently stayed pending the outcome of the criminal investigation

-

2We should stress that Intertrust and Equiom are businesses with good reputations and we are listing them as examples of what we consider good practice.

- 3

-

4With a few exceptions, for example if the unknown party was a consortium in which no person held more than 25% of the company

22 responses to “The PPE cover-up: Douglas Barrowman’s hidden ownership and the potentially criminal consequences”

Hi Dan, a very concise and interesting article. I did note that Barrowman made some flippant comment to Laura Kuenssberg in the interview that… (along the lines of) that he has hidden his identity for years using family members. Was this an admission? I recall (pre retirement) having to check clients as part of the AML checks and identifying who the PSC was and getting full details. This seems totally pointless if people can get away with this.

He mentions it after 20 minutes 30 seconds of the interview with Laura Kuenssberg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLCAqZBvnT4

I noted that Mr Barrowman said he had paid all the tax due on the £60 million in the Isle of Man. I assume that this amounted to the square root of SFA since the rate of corporate tax on the IOM is zero?

its always the rich who manage to get away with it!

In the light of the “car-crash” interview on Sunday, the accounts for PPE Medipro for the 11 month period to April 21 are interesting. They are abridged, of course, but indicate that the profit as £3.9m. However, in the interview they admitted they had made about £60m profit – which raises the question of where the rest of the profit was supposedly earned.

something very odd was going on

Dan, the PPE Medpro contract document in the Contract Award Notice https://www.contractsfinder.service.gov.uk/notice/79397607-466e-4891-b091-3307fd5819d9?origin=SearchResults&p=1 shows a contract value of £122 mn excluding VAT but the government’s particulars of claim lodged at the High Court https://media.licdn.com/dms/document/media/D4E1FAQGWrqwoNgk4wg/feedshare-document-pdf-analyzed/0/1685296788787?e=1693440000&v=beta&t=pw8PrxWFaUoEzJBwlN0uXgTFPU4fASNyTZm8v-BrqrE quotes the contract value as £122mn including VAT. If the government’s claim includes the recovery of VAT paid by DHSC to the supplier, this could mean that a similar situation has arisen on other disputed contracts, and the loss to the taxpayer is potentially 20% higher than the quoted ex VAT contract values published by the government. As most PPE contracts involved unsecured advance payments before the PPE arrived, it seems possible that DHSC made huge VAT payments to the PPE suppliers before realising that PPE was not acceptable and did not mitigate the massive risks of making advance payments by at least holding back VAT payments until the PPE was determined to be acceptable. Appreciate your thoughts.

Great article. There are some additional factors that make this considerably worse. On top of what is stated, Knox is Regulated by the Isle of Man Financial Services Authority. They have very strict rules as to how TCSP’s (Trust and Corporate Service Providers) operate. Included within the rules are limits to numbers of directorships one can hold. Your discussion on shareholders is correct. One commentator suggested an investment company. Again there are very strict rules and licences governing such activity on the Isle of Man. Many more questions arise when one starts to follow the money. I am not sure if PPE Medpro was incorporated in the IOM or England and Wales, which will have to be considered. It seems odd however that as an IOM resident Page detailed an English correspondence address. I suggest you follow up with the IOM FSA.

Fascinating investigation (and research) on your behalf. Is it possible that as time passes, this investigation (and many others) will fizzle out because convictions will bring too much scrutiny back to the current Government Ministers and their “VIP Lane” awarding of contracts. |I hope not but do fear this will be the case…

I don’t for a second think any Government Minister knew what was going on. If I’m right about what happened (and I may not be) then this was a scheme to deceive the Government.

Fraud on a grand scale the police after mone’s interview will now investigate 2 yrs bird for barrowman and mone awaits

sadly one cant help feeling that this will all disappear and there will be no action taken against anyone; Companies house appears to be as much as a shambles as HMRC.

Logical article, but one point left unexplained. Could Barrowman claim to be an “individual with significant control over the company who is “non-registrable” in relation to the company” 790M (4) ?

No – that would only be the case if Mr Barrowman held through a company that was itself registrable as the PSC, and that company disclosed Barrowman as the PSC. Or multiple tiers with the same principle.

The point of 790M(4) is to avoid duplication – it doesn’t have the effect of hiding the identity of individual controlling a group.

A very interesting article which highlights in a different area, the concerns we have harboured for many years over the ownership of the AML entities involved in “disguised remuneration” planning since 2007. It seems that even HMRC and the Tribunals have been unable to untangle the true ownership of the entities although they certainly seemed to do as directed by persons holding senior posts in AML.

SPV + bad-leaver?

A fascinating article as always, Dan. However, one possibility which you didn’t canvas (I guess a variation of your first scenario) is that Lancaster Knox alongside being a CSP has elements of a private equity firm to it – allowing the Lancaster Knox partners to “co-invest” their own money in a variety of investee companies. (Alternatively, their investment might be an employment-related security, as a reward of their employment (and presumably reported as such for income tax purposes). If that were the case but there some overarching “bad leaver” provisions in the Lancaster Knox “partnership agreement” then that would (just about) be consistent with Page being required to transfer his shares to Lancaster on leaving.

Admittedly the facts here don’t look like a “co-invest” as the Confirmation Statements seem to show Page as the owner of all 100 ordinary shares and then Lancaster as the owner, whereas for a co-invest you would obviously expect there to be other shareholders. But I guess with a lot of companies under a CSP, it is possible to envisage that different Lancaster Knox people might be given different SPVs to invest in. It certainly wouldn’t be unheard of for a senior employee in an organisation to be given the opportunity to branch out into a side-project set up under its own SPV, but with some overarching bad leaver provisions as part of their main employment.

I haven’t tracked through what such an SPV+bad-leaver model would require in terms of the PSC register and whether the controller of the overarching employment should also be registered as a PSC. But I think it is at least a possibility.

Hi John and thanks – I agree that the share structure doesn’t look much like a co-invest. It also contradicts the explanation Mone gave the FT, and the known features of Barrowman’s business. But if that was what was happening, I believe the controller of the employment should then be registered as a PSC – for most PE funds there are sufficient people holding the reins that you end up with no PSC, but Barrowman is more of a one-man band.

“Concise clear reporting” is an understatement. This is a superb story, crystal clear, highly compelling and very convincing.

Whilst I admire and support your work here Dan, may I ask why you describe Mr Page as an ‘accountant’? I appreciate it’s not the most significant element of the story but it risks further tainting my profession. Mr Lancaster, on the other hand IS an accountant ;-(

Whilst I know anyone can call themself an accountant, I can’t see that Mr Page has done so either in the profile referenced above, or on his Linkedin profile. So why have you? (The closest he comes is mentioning he is a member of STEP)

you are completely right – I will make both changes. I had missed Page was a member of STEP – we should consider referring him for a breach of the STEP professional conduct rules.

Concise clear reporting. Whilst I hope that Mr, Lancaster is appropriately sanctioned by the professional bodies of which he is a member, I’m not holding my breath. There is an inherent conflict. As far as I understand it only The Law Society have dealt (or have had dealt) with it. You can’t be a white collar union and a professional standards tribunal at the same time.

I can’t claim to have reviewed any historical charters, but from my ICAEW training last century my understanding is that the professional bodies were set up to benefit their members by distinguishing them from “cowboys”; they applied entrance requirements, and the disciplinary process was to kick out any member with low standards or who did wrong so dragging down the reputation of the body as a whole.

There is an obligation (not just a right) to report fellow-members one suspects of wrong-doing.

If you saw your partner doing something wrong, you reported them, or faced disciplinary action yourself (it would be interesting to search the archives to find whether this did ever actually happen)

This obligation is now being breached continually, partly because there are so many members.

In practice I get the impression that the professional bodies now only investigate after complaints by clients, news reports of convictions, complaints by public servants (E.g. HMRC inspectors, judges) or complaints by members of the public.

The last are very rare – Dan may have a monopoly in recent years?

An obligation to report statistics of each type (including by fellow-members), and a journalist compilation of them would be interesting.

Perhaps FOI requests could get something useful?

Dan – can you tell us whether in your time at CC were you ever aware of the firm or a partner reporting misconduct by members of their own or other professional bodies, and if so, an indication of the volume?

law firms rightly centralise such reporting so, whilst I wasn’t aware of anything, there’s no reason I would have been. However, I will say this kind of stuff was taken very seriously – I was one of a number of partners who tested potential new partners in ethical behaviour and misconduct, and the process was generally seen as extremely rigorous.