Uber’s latest financial reports, filed yesterday, reveal that HMRC is challenging its VAT position and claiming £386m. Uber is appealing but has had to pay the disputed VAT up-front.

Uber historically charged no VAT. It said it was just an app, with its drivers supplying the service to customers. As most drivers‘ income fell below the VAT threshold of £85,000, that meant Uber rides were free from VAT. That was challenged by HMRC in 2022, with Uber paying £615m. Many people expected Uber to then charge 20% VAT on its fares, but it instead used the Tour Operators Margin Scheme to pay a low effective rate of VAT HMRC is now challenging that.

UPDATE: Uber just got in touch to confirm that I’m correct that the new dispute is about TOMS; but I was wrong to think the 2022 settlement was on the basis of TOMS – it wasn’t.

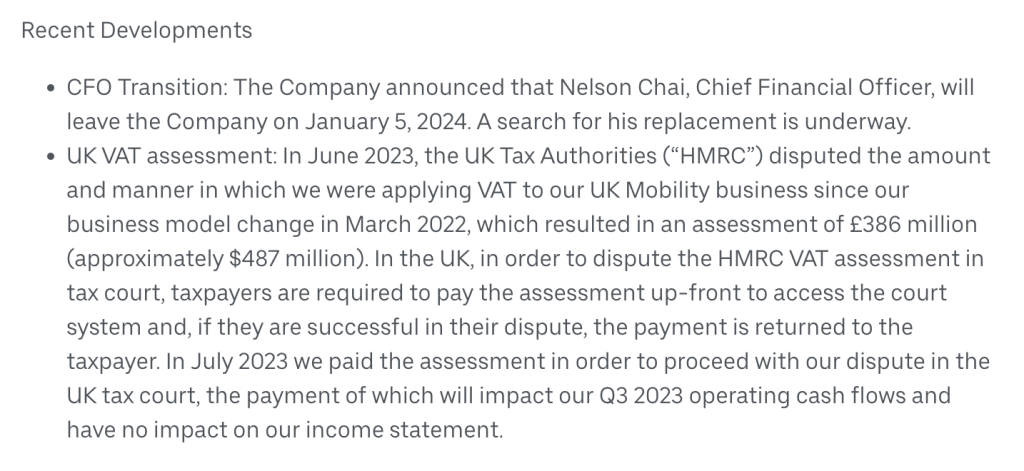

The new disclosure

It’s in Uber’s Q2 2023 results:

The background

Most businesses charge VAT at 20% on their goods and services. But the UK has an unusually high VAT threshold of £85,000 and, as most taxi drivers earn less than that, most taxis don’t charge VAT.

That was historically the case for black cabs, and for most private cabs. They might be coordinated by booking service, but realistically the drivers are independent businesses and the booking service is just their agent. Each driver pays a fee (say 10%) to the booking service, and that would be subject to VAT, but the fee the driver charged the customer is the fee for his services, and so no VAT applies.

Uber’s position was more interesting:

- Uber said it was the same as a normal taxi booking service, and was just an agent for the drivers – so the fares were not subject to VAT1 in principle, they should’ve been if the driver earned over £85,000; I’m not sure how this was dealt with in practice, and it may never have happened.

- But in tax terms, Uber was pushing their luck. Uber controls many aspects of their drivers’ business; it’s more than a mere agent, and so it always seemed more plausible that Uber was the “principal”.2The original version of this paragraph said that Uber was an outlier compared with other taxi firms; StuartW in the comments below gives good reasons to doubt that was correct. That meant they should charge VAT.

- Uber’s position became hard to defend after, in a March 2022 employment law judgment, the High Court confirmed that Uber was indeed the principal, following a Supreme Court decision that Uber drivers were “workers” and not self-employed.

- HMRC eventually agreed – they asserted VAT was due and Uber caved and paid up £615m in an agreed settlement with HMRC.3The first draft of its article This followed legal action by Jolyon Maugham KC4HMRC say they were always going to challenge Uber anyway and the timing was a coincidence

Uber saw this as putting it at a competitive disadvantage against other taxi firms, and so it looks like it has started to litigate to ensure VAT is also applied to its competitors.5It did seem to me that Uber is different, but the High Court in the Sefton case didn’t agree; see also the comment from StuartW below.

The new Uber model

A normal person, or even a normal tax advisor, might think that Uber having to charge VAT meant a 20% increase on all fares. Uber would be able to recover VAT on its expenses (“input VAT”), but this won’t be much – Uber’s main expense is paying drivers, and they mostly/all earn too little to charge VAT.

But there is something called the “Tour Operators Margin Scheme” (TOMS).

Say I am a travel agent. I put together a package holiday involving a whole bundle of different services: hotel, flights, coach services, restaurants, train tickets, etc. Potentially across multiple different countries. In theory, I should be charging my client 20% VAT on the package holiday, and recovering input VAT on those costs are incurred that were subject to VAT. But all the different countries mean my VAT position would be an unholy mess. TOMS says: yeah, it’s all too difficult. Let’s not bother with the usual VAT accounting. Instead, I’ll just account for 20% VAT on my profit margin. That’s TOMS.

Uber takes the position that TOMS applies to it. It is buying the drivers’ services, and no doubt other ancillary services as well, and then supplying a bundle to the customer in the form of their ride. You might well say; hang on, Uber is not a tour operator. However, TOMS does more than it says on the tin, and even the HMRC guidance goes out of its way to say that it can apply in cases where outside a classic tour operator.6The technical background is well explained here, but it’s subscription only

The consequence is that it is only Uber’s profit from each ride which is subject to 20% VAT. That is probably why Uber paid only £615m, and why Uber’s fares did not noticeably increase after it started charging VAT.7Uber has been stupendously loss-making for most of its existence, but from a VAT perspective that doesn’t matter, because VAT looks only at the income and costs attributable to a particular ride. Other elements responsible for Uber’s losses (such as all those coders and their expensive coffee, servers, marketing, cost of capital, etc) won’t be relevant here

The other consequence is that a business hiring an Uber taxi cannot recover VAT on the fare. That stands to reason because VAT is not the normal 20%, but some smaller amount which the business cannot know.

The new £386m claim

The disclosure doesn’t say, but my understanding from a well-informed source is that HMRC is claiming that Uber can’t use TOMS, so that Uber has to pay an additional £386m. This is very plausibly the difference between TOMS and standard VAT on one year of Uber’s revenue.8To ballpark this: Uber’s fee income is c£800m and its gross income is c£2.6bn. So the difference between TOMS and normal VAT for one year will be around 20% x (£2.6bn – £800m) = £360m.

The conditions are pretty simple:

- Uber must be a “tour operator”

- it must buy in supplies from another person (the drivers)

- those supplies must be “resupplied without material alteration or further processing”

- and Uber must supply them from an establishment in the UK, for the direct benefit of a traveller

All of these are easy, except the third. The most likely HMRC challenge is that Uber is not at all like a travel agent, because it shapes every aspect of the taxi driver’s services, so that there is “further processing” or “alteration” of those services. Importantly, the driver doesn’t control his or her pricing, and may not even know how much Uber charges.

HMRC recently made a challenge on a similar basis to a business that leased apartments and then let them to tourists. The “alteration” here was that the taxpayer painted the apartments and provided furniture. The taxpayer won; these alterations were found to be “superficial and cosmetic”. The case is Sonder Europe, and the judgment is here.

There’s another more ambitious and fundamental way in which HMRC could challenge Uber’s use of TOMS. It could argue that the drivers are in fact employees of Uber. In that case, there are no supplies bought-in, and TOMS cannot apply. The whole taxi fare becomes subject to VAT.

If I was HMRC I would run both arguments.

Is this tax avoidance?

There is no single legal definition of tax avoidance. I’ve written more about that here. But, for what it’s worth, I think Uber’s original approach was tax avoidance, because they were artificially taking a position that VAT was not due, when on the face of it, it was. The fact Uber backed down without a fight adds strength to this.

However, the question of whether TOMS applies is a dry technical question which does not relate to any particular structuring or act of Uber. Uber’s approach seems legitimate to me, whether or not it ultimately turns out to be correct. If we don’t like TOMS being used in this way, we can change the law.

Who will win?

That is hard to say. This is a difficult area with little relevant authority, and neither I nor our regular team of experts have sufficient experience to be able to call it. Both Uber and HMRC may think they have good arguments.

Given that, and the amounts involved, we can probably expect it to be appealed at least once, and possibly several times. It’s not unusual for this kind of dispute to take ten years. But, with VAT, you “pay to play”. Uber had to pay the £386m upfront. As time goes on, without the dispute being resolved, Uber will have to pay additional amounts upfront, reflecting the position that TOMS does not apply. Only if Uber eventually wins does it get its VAT back.9 Corporation tax and income tax don’t work this way at all. You almost always get to keep the tax while you dispute it, and only have to pay it to HMRC (plus interest) if you lose your final appeal. There is, needless to say, no rational basis for the distinction.

An Uber spokesperson told me “Uber is seeking clarity for the whole industry in order to protect drivers and passengers.”

Update 3 August: I belatedly remembered the way US accounting works for indirect tax disputes. We can deduce from the way the Uber disclosure is phrased that Uber has been advised that it is “more likely than not” to win the dispute, and recover the VAT back. It has therefore booked a receivable in its accounts to reflect that eventual recovery – that’s why the statement says there is a cash impact, but no impact on the income statement (because the £386m debit for the VAT is cancelled by a £386m credit for the receivable). Uber has confirmed to me that this is indeed the position.

In my experience, US corporations take these issues very seriously, and require clear advice before their accounting personnel and auditors permit such a receivable to be booked. Of course that doesn’t necessarily mean Uber will prevail – HMRC may also be confident of its position. But it does mean this is much more than a try-on. Asking around, there’s no clear view amongst VAT experts on who will win here.

What’s the consequence for the taxi industry, and our fares?

The outcome of the Sefton case means that the entire private taxi industry (i.e. not black cabs) will be affected by the result.

If Uber win, then we will continue with most of the taxi fare being outside VAT, and only the taxi firms profit margin being subject to VAT at 20%.

if Uber lose, then, unless I am missing something, the entire fair charged by taxi firms will be subject to 20% VAT. But, if you book a private car directly with the driver, there won’t be VAT. That seems a very distortive result, that would drive economic inefficiency. We all benefit from being able to book taxis in a centralised way, i.e. over the phone or on apps, and it seems crazy for tax to push in the other direction.

What about black cabs?

individual black cab riders usually earn less than £85,000, and so don’t charge VAT.

The centralised black cab booking services appear to use the same structure as Uber used before 2022, with the booking service, saying it is merely the agent for the driver. The judgements that stopped Uber and other private taxi services from operating in this way don’t apply to black cabs.

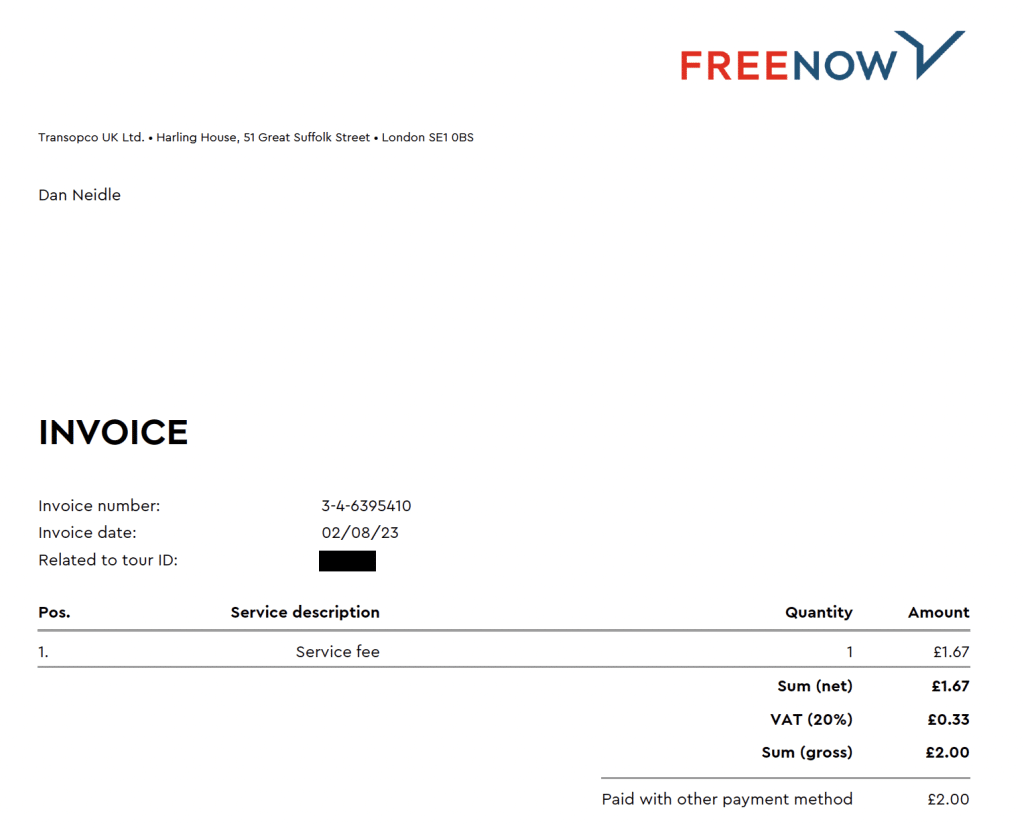

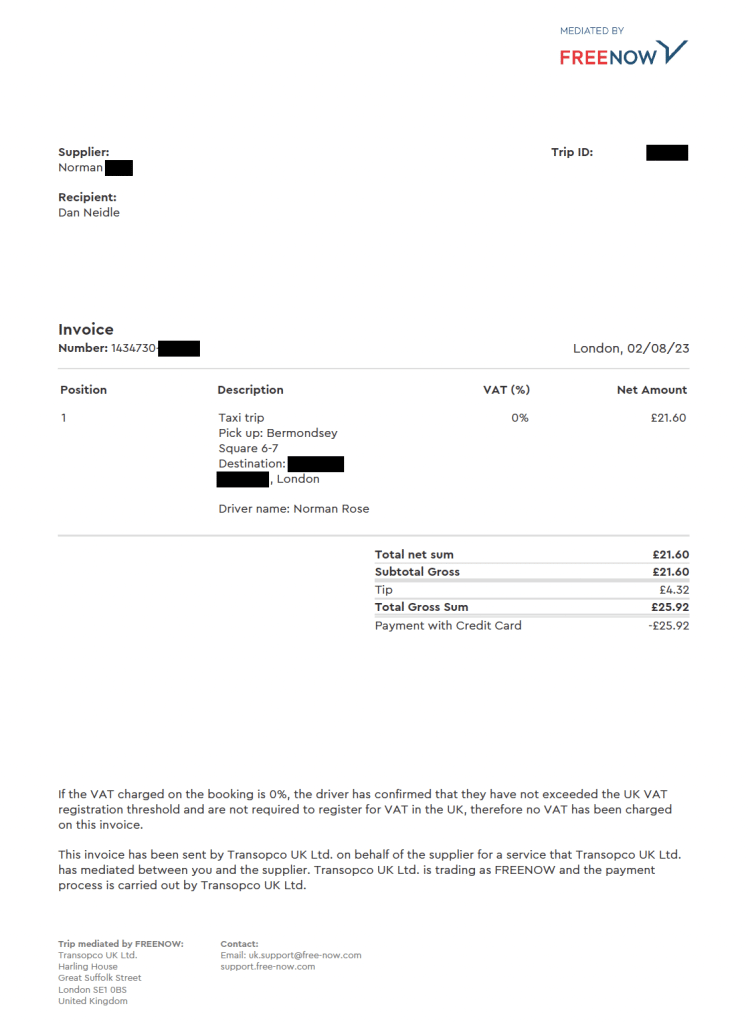

So, when I booked a taxi with FreeNow yesterday, I received two receipts.

First, the platform’s fee, with VAT.

Second, the driver’s fee, with no VAT:

The paragraph at the bottom gives away that the agency structure is being used.

Should the Government change the law?

This all seems very odd. There’s a plausible case that the TOMS rules should be amended, so that TOMS only applies in cross-border cases where there is a real need for it to apply (and, post-Brexit, the UK can easily make changes of this kind to our VAT system). That wouldn’t change Uber’s historic position, but would ensure full VAT applied going forward. Changing the law would be very easy; it looks like HMRC can just designate taxi firms as outside TOMS. There’s even an argument for abolishing TOMS – in the modern world it looks less like a simplification, and more like a hand-out.

But that would just formalise the distortive economic result that booking a taxi directly results in no VAT, and booking through an app means 20% VAT.

But the real problem here is the high VAT threshold, which (if Uber lose) will be responsible for a 20% cost difference between booking a taxi directly and booking one through an app/phoneline. That is, in my view, unjustifiable – it’s economically distortive and drives tax, evasion, tax avoidance, and uncertainty/tax disputes. The threshold should come down (enabling a VAT rate cut at the same time).

So I have to say that, from a policy standpoint, I hope Uber wins (so that there’s mostly no VAT on any taxi fare), or that the threshold is cut (so there’s VAT on all taxi fares).

Let’s just hope we don’t end up with other fudges, like a 0% rate for taxis, which would further erode the tax base and create opportunities for avoidance (e.g. by combining other VATable services with a taxi ride)

Thanks to B for the tip-off and expert input on this.

Photo by Viktor Avdeev on Unsplash, edited by us

-

1in principle, they should’ve been if the driver earned over £85,000; I’m not sure how this was dealt with in practice, and it may never have happened.

-

2The original version of this paragraph said that Uber was an outlier compared with other taxi firms; StuartW in the comments below gives good reasons to doubt that was correct.

-

3The first draft of its article

-

4HMRC say they were always going to challenge Uber anyway and the timing was a coincidence

-

5It did seem to me that Uber is different, but the High Court in the Sefton case didn’t agree; see also the comment from StuartW below.

-

6The technical background is well explained here, but it’s subscription only

-

7Uber has been stupendously loss-making for most of its existence, but from a VAT perspective that doesn’t matter, because VAT looks only at the income and costs attributable to a particular ride. Other elements responsible for Uber’s losses (such as all those coders and their expensive coffee, servers, marketing, cost of capital, etc) won’t be relevant here

-

8To ballpark this: Uber’s fee income is c£800m and its gross income is c£2.6bn. So the difference between TOMS and normal VAT for one year will be around 20% x (£2.6bn – £800m) = £360m.

-

9Corporation tax and income tax don’t work this way at all. You almost always get to keep the tax while you dispute it, and only have to pay it to HMRC (plus interest) if you lose your final appeal. There is, needless to say, no rational basis for the distinction.

25 responses to “Exclusive report: HMRC pursuing Uber for another £386m of VAT”

I bought a brand new car for sole use as a PHV. I exclusively work for Uber. How can I claim my VAT of £10K back as I am not required to pay VAT, I can register for VAT – won’t meet the threshold – so what do I do? I’d like to charge VAT on rides, but cannot now?

sorry, we can’t provide tax advice to individuals. In principle you can register for VAT and claim the VAT back, but I don’t know how it would work in practice (and if Uber permit that).

Lee Ward, not sure who your question is aimed at, but I’ll have a go. And my browser doesn’t seem to want to post a reply beneath your own post, so presumably this will appear at the bottom of the pile…

Anyway, I’ll use the terms hackney carriage (HC) and private hire vehicle (PHV), because officially a taxi is a hackney carriage (most obviously a London black cab), but the term ‘taxi’ is often used generically, which causes a lot of confusion.

But you don’t say whether the driver co-op is HC or PHV, or perhaps both – mixed HC/PHV fleets are fairly common, particularly outside the big cities. But the Sefton case was all about how *PHVs* are regulated with regard to the licensing legislation and the booking process, and to the extent that the legislation as construed by the judge considered the licensed PHV operator to be the be contractual principal, from which the VAT consequences arise.

(One source of confusion is that HCs outside the big cities aren’t always traditional black cabs. They can be standard cars like Mondeos and Passats, thus are often conflated with PHVs. In turn, PHV is the legal terminology for what was often traditionally known as a minicab. Thus a PHV is effectively a licensed minicab, and encompasses Uber and other more modern app-only booking platforms.)

So if the co-op is licensed as a private hire operator (ie informally an ‘office’, or a ‘circuit’, or app-only platform like Uber, Bolt, Freenow or Ola), then according to the Sefton judgement the co-op will be deemed to be the principal for VAT purposes, therefore I can’t really see how it would be regarded as any different to Uber, except for the obvious difference in scale (and assuming, of course, that collectively the co-op’s vehicles exceed the VAT threshold in terms of total fares, which it very probably will, as will any licensed private hire operator except the very smallest one-man-band or maybe a small fleet of two or three cars). And whether the despatch operation is structured as a co-op, sole trade, partnership or limited company shouldn’t make any difference either, in my non-expert opinion – it’s the fact that the entity is licensed as a private hire operator that’s the salient point, and to that extent any consequences flowing from the Sefton case become relevant.

On the other hand, if the co-op you mention is an all-HC circuit, then the booking function is unregulated, and to that extent the Sefton case is irrelevant, and there are no VAT consequences.

But that’s something I just don’t understand, particularly from the perspective of practicalities and economic substance. The judge in the Sefton case simply dismissed the relevance of HCs because they ‘ply for hire’ (para 30 of the judgement). But in practice, and particularly in the provinces, many HC work from offices or circuits, and to that extent are substantively the same as PHVs (although the HCs may also ply for hire, obviously, which PHVs can’t legally do).

So although my knowledge of taxation and licensing law is probably nearer to ‘sketchy’ than ‘expert’, it seems odd that a vehicle and driver doing substantively the same thing in terms of booking and despatch will or won’t come within the ambit of VAT on fares purely because one booking and despatch operation (the PHVs, as per the Sefton case) is regulated by legislation , while the other booking and despatch operation (HCs) isn’t regulated at all.

To my mind this is most obviously anomalous with regard to the mixed HC/PHV fleets that operate in the likes of Brighton and Dundee. If someone books a ‘taxi’ in Brighton, for example, will the VAT position depend on whether the despatch operation sends a PHV or an HC?

Another obvious anomaly is that in Brighton Uber uses HCs licensed by Lewes Borough Council, because the vehicle and driver specification (ie barriers to entry in economic terms) are a lot easier to meet in Lewes than in Brighton. So to that extent, if Uber is charging VAT on fares in Brighton, chances are it could be for a trip actually performed by an HC…

The likes of Dundee is also interesting, because in all the cases and articles I’ve read arising from the Uber VAT thing, I can’t recall Scotland being mentioned once.

Yet VAT law applies throughout the UK, but to the extent that the Sefton case is only about PHV licensing law in England, then are HCs and PHVs in Scotland to carry on regardless as regards VAT, while the trade in England is turned upside down? Scotland has different licensing legislation, and to that extent the Sefton case is irrelevant. But does this mean a kind of binary VAT system for the Scottish and England industries, which are substantively identical in terms of practicalities and economics, but use different licensing legislation? (Another interesting point perhaps is that in terms of booking and despatch licensing, there’s no difference between HCs and PHVs in Scotland.)

Anyway, that’s just a few questions I’ve been thinking about in a personal capacity. Any thoughts from Mr Neidle or others obviously welcome.

Another point re the co-op thing that comes to mind, though, is that the VAT and employment status questions are often portrayed as largely parallel. But maybe a co-op demonstrates where the two would be quite distinct – if it’s a licensed private hire operator then the Sefton case is relevant regarding VAT, but it seems a stretch to conclude that an owner-driver who’s a member of the co-op should be regarded as anything other than self-employed vis-a-vis the co-op.

On the other hand, I suspect purely equal and non-hierarchical co-ops are relatively rare in the industry. Some owner-drivers working for the circuit may not be *members* of the co-op, and to that extent the co-op is their Uber in terms of employment status, or at least that’s my view of how it should be. Likewise, other drivers may be taken on to drive a vehicle that isn’t theirs (so-called journeyman drivers).

But the thing with the Uber employment status case is perhaps that it’s not only a huge operation, but it’s homogeneous, too. In terms of the more traditional trade, a typical city will have several different despatch operations, all at least slightly different, HC and PH, or mixed. Across the country, the trade is highly fragmented, and encompasses thousand of different despatch operations. So not so easy to compare to Uber in terms of the Supreme Court judgement on employment status, and again the accepted wisdom seems to be that Uber is largely sui generis (as the lawyers might put it!) and, likewise, HCs are also a different beast entirely.

But in terms of the legal tests applied in employment status cases like control, subordination and dependency, I’m quite sure the courts would deem tens of thousands of non-Uber HC and PHV drivers as worthy of the ‘third limb’ ‘worker’ status, assuming any litigation or legal action got to that stage.

But the fragmented and generally local nature of the industry probably militates against grassroots drivers taking action against their circuit in terms of employment status. And a driver or two taking on the average high street minicab firm is in many ways not quite as straightforward as a substantial trade union taking on a global behemoth like Uber.

But an interesting (although obscure) recent Employment Appeal Tribunal case concluded that a journeyman driver on an HC circuit in Bournemouth should be afforded ‘worker’ status (United Taxis Limited v Comolly/Tidman). I’d guess that tens of thousands of drivers in the UK are in a similar position but currently deemed self-employed.

Anyway, that’s just a few thoughts, and obviously any input from tax or employment law experts welcome! (Would have included a few hyperlinks, but not sure if they’re allowed on here…)

wow – you clearly know the business extremely well. The Christopher Johnson case is also interesting https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/uk/cases/UKEAT/2022/6.html

My view is (1) the current regulatory/employment/VAT position (across the UK and different taxi types) is an unholy mess, and I don’t pretend to understand it, but (2) from a policy perspective, all taxi rides should have the same VAT treatment.

(I think you probably can’t post links; sorry. Spam got out of control)

Thanks – I did read a summary of the Christopher Johnson case last year, but to be honest had totally forgotten about it! But that case maybe underlines that, just like Uber on the PH side, the London HC trade is reasonably homogeneous, and any relationship the London HC drivers have with a despatch operation or app is a tad tenuous and that it’s substantially closer to genuine self-employment than worker status. (And the Johnson case in particular looked more than a tad opportunistic.)

On the other hand, the Comolly EAT case in Bournemouth demonstrates how messy the spectrum between self-employment – worker – employee can be, and maybe underlines why commentators won’t readily compare it to the Uber employment status judgement. So, for example, any mainstream press comment on the industry generally is often viewed as a binary between the London HC trade on the one hand, and Uber on the other. In the provinces, and in the non-Uber trade, it’s a lot messier, and not so amenable to the crude binary.

The United Taxis operation in Bournemouth underlines that – it’s a mixed HC and PHV circuit, and even on reading the case summary, I struggle to see how its PHV drivers are any less controlled by, subordinate to and dependent on the United Taxis platform than PH drivers working for Uber, yet all its drivers are almost certainly deemed self-employed. By the same token, as the EAT judgement makes clear, while HC drivers working for United Taxis may do some plying for hire work, this is probably minimal compared to the pre-booked jobs fed to them by the despatch platform, and to that degree there’s a large element of dependency.

The case also illustrates the issue of multi-driver vehicles, which is generally absent in any discussion on either London HCs or Uber, but encompasses thousands of drivers elsewhere, and means that, to a degree at least, the hours individual drivers can work is constrained, meaning an element of control and subordination in employment status terms.

Likewise, and related to the multi-driver vehicle angle, fundamental to the Comolly case is that the driver didn’t actually own the vehicle. Again this is a reasonably common arrangement for drivers deemed self-employed, while the Uber drivers found to be workers by the Supreme Court will almost certainly exclusively drive their own vehicle.

In this regard it’s maybe also instructive that the Bournemouth firm also uses its own app, as indeed is almost the norm these days for any HC and/or PHV despatch operation of any size. Of course, most will still accept more traditional phone bookings, but the app dimension should underline the similarities with Uber in terms of the practicalities. (And that Uber as some kind of ‘ride-hailing’ platform rather than ‘taxi’ provider is more neologism than substantively different in practical and economic terms.)

Another significant development that should concentrate official minds is how Uber’s UK expansion has continued in recent years. As far as I’m aware, Uber hasn’t really expanded into any significant new town or city for some years now. Instead, it bought the Autocab despatch software, and utilises the traditional firms using that software to supply vehicles to any customer looking to book an Uber car via the app – this ‘Local Cab’ angle is maybe a quick, easy and less costly way to enter new markets.

But, hithertoo at least, the vehicles despatched to the passenger using the Uber app by the local firm will almost certainly be driven by self-employed drivers and, hitherto at least, when despatched directly to their own customers, the ‘Local Cab’ firm won’t be charging VAT. But Uber’s ‘Local Cab’ option surely underlines the parallels between Uber and the established industry.

Anyway, presumably HMRC will be quite pro-active as regards VAT compliance, and to that extent the industry may witness fundamental change pretty soon. Ignoring the likelihood of appeal, obviously! (And local licensing authorities may have some remit in that regard insofar as they decide whether private hire operators are ‘fit and proper’ to hold a licence.)

On the other hand, presumably the employment status question depends on individual actions rather than the impetus coming from HMRC. And local authorities certainly show zero interest in that angle. So unless something significant happens at the political/central government level, I’d guess that, even though my opinion is that tens of thousands of drivers are misclassified, any movement in that regard will be fragmented and piecemeal.

I think the threshold for the recognition of the receivable will be probable (ie 75%) rather than more likely than not (>50%). The MLTN threshold is for uncertain tax provisions under ASC 740 (which applies for below the line taxes like corporation tax not VAT). Assets usually have a higher bar. Unless there’s something specific to VAT receivables under US GAAP that I’m not aware of.

You are quite right. A year out of practice and I get sloppy… I’ll amend!

“No impact on our income statement” sounds like Uber had already provided for the liability in their books. It might be worth checking their balance sheet what else might be there.

The other alternative is that they are more than 95 per cent sure they will win the dispute, which I think would be a very brave piece of accounting.

Re “pay to play” I’m wondering if it might be a vestige from times when the UK was supposed to hand over a part of the collected VAT to the EU. Now of course it can be used to fund the NHS instead. But there may be some inertia in the system.

Interesting, and kind of explains comments made by major players in the private hire trade about the application of the TOMS scheme following last week’s Sefton case. And, if forced to become principals following the Sefton case, the scheme they wanted to use themselves. But they gave the impression that HMRC had agreed the scheme with Uber, but obviously that’s not the case:

“One of the questions raised by these rulings is, which is the appropriate VAT regime for the whole Private Hire industry? Crucially it is likely that private hire operators will qualify to apply VAT on their margin from each trip rather than on the full fare. The latter would have significant implications for the entire industry and its passengers.

“Uber would claim they have been following HMRC’s own guidance (VAT Order 1987) to apply VAT on the margin of a trip. Other operators including Bolt and FreeNow have been doing the same, as stated on their invoices.”

Anyway, I’m certainly no tax expert, but I do know how the taxi and private hire trade works, and to that extent totally disagree with your claim: “Uber controls every aspect of the drivers’ business. Quite unlike a normal taxi booking service.”

In fact, in the main I’d say Uber exerts less control than many ‘normal taxi booking services’. In particular, what was genuinely new about Uber (ignoring vacuous PR constructs like the ‘gig economy’ and ‘ride-hailing’) was that Uber drivers didn’t have to fully commit to working with Uber. On the other hand, traditional cab firms would always require an exclusive commitment, or the driver would be dispensed with pronto.

Likewise, many quite substantial operations require drivers to wear some form of uniform, for example, or they rota drivers (particularly in less urban locations), while neither of those requirements have ever applied to Uber drivers.

And, most obviously, the ‘platforms’ (whether a more traditional one, or an-app only provider like Uber or Bolt) always agree the pricing with the end-customer, and the drivers have no say in fare-setting at all.

I’d guess that Uber was essentially regarded as a tall poppy by Jolyon Maugham KC, who thought Uber was a different beast as compared to the traditional industry. But the Sefton case has arguably put paid to that. Likewise, the other prong to Uber’s tall poppy status has been the related employment status question, but again it’s probable that ‘worker’ status is even more apposite for much of the mainstream industry than Uber. As indeed the judge seemed to allude in last week’s judgement at para 83.

And as regards your footnote 4, I think the judge was only scratching the surface as regards the parallels between Uber and the traditional industry. The similarities seem more important to me than the differences.

Brilliant explanation of the trade, thank you.

How would you see a driver Co-Operative working under this ruling when the drivers own the company collectively, make no profit and supply the vehicles themselves?

the link to the taxation article [footnote 5] is broken. seems to need an additional hyphen at the end!

https://www.taxation.co.uk/articles/readers-forum-is-there-vat-on-uber-taxi-rides-

Thank you!

thanks – you clearly know much more about the industry than I do… I’ll amend the piece

TOMS was always a cinderella area of VAT most tax advisors avoided it and few in HMRC had detailed knowledge, running a TOMS argument is interesting. If that bloke is still sat on the Clapham omnibus then Uber is no TOMS outfit surely? But then again he probably has never read VAT Notice 709/5!. Incidentally as Uber operates world wide how does it account for VAT and where does it have its business establishments?

The Supreme Court in Uber BV v Aslam and Ors held that the taxi drivers were workers (aka limb ‘b’ workers), not employees. Such workers have rights but of limited scope when compared to employee rights.

I am not a tax specialist but the status of the drivers has been decided in the case mentioned above. My question is whether your suggested ambitious and fundamental challenge by HMRC would work with drivers who are limb ‘b’ workers.

A minor potential editing issue:

At least on my phone, the section on ‘The New Uber Model’ seems to appear both in the main text and under footnote 3.

hopefully now fixed!

Interesting article – re the “further processing point” also worth noting the FTT’s comments in Sonder at 78 which could be picked up by Uber:

“The UK notion of alteration and further processing does not appear in Directive. Nowhere in ECJ case law does it say that bought-in supplies that are altered or subject to processing must be excluded from the EU special scheme. As I have concluded that furnishing an apartment did not constitute a material alteration to that apartment or further processing of it, I do not need to consider whether the exclusion from the TOMS of goods or services which have been materially altered or processed by the tour operator is consistent with the EU special

scheme in the PVD”.

Superb report and analysis as usual Dan. But may I question the final line of your notes where you say: There is, needless to say, no rational basis for the distinction.?

You may be right and you may have a much more detailed understanding of VAT rules than I do.

In my experience when I cannot see a rational explanation for a tax rule, it doesn’t mean there isn’t one. It simply means there isn’t an obvious explanation . At least not one that is obvious to me.

I reckon at least 10% of the time there is no rational explanation! But I’ll ask around and see if anyone has an idea. My speculation: HMRC obviously likes being paid upfront, but politically this is too hard. The introduction of an entirely new tax – VAT – gave it the opportunity to get what it wanted.

There is a simple explanation – Customs and Excise were given management of VAT, not Inland Revenue, in 1972. VAT replaced purchase tax, and if you search the Purchase Tax Act 1963 for the word “appeal” it is missing, though there was a cumbersome system for disputing wholesale values by referring the dispute to, yes, a referee appointed by the Lord Chancellor (whose decision was a final). To do that the referrer had to have deposited with the Commissioners of C & E “the amount of the tax appearing on the basis of their [CCE’s] opinion to have become due.” – s 36(2). It is hardly surprising that when forced to introduce an actual appeal system (s 40 FA 1972) it was as grudgingly restrictive as possible, with not only a requirement to pay the tax in dispute upfront (subject to a meanly interpreted exception for hardship) but you could only appeal if your VAT affairs were completely up to date and you had paid all the VAT due – s 40(2) FA 1972. That is still the case for most VAT appeals, and I think for the recently (since 1994) introduced systems of assessment and appeals for other indirect taxes.

Brilliant explanation of the trade, thank you.

How would you see a driver Co-Operative working under this ruling when the drivers own the company collectively, make no profit and supply the vehicles themselves?

Interesting Richard, I’ve read certain parts of the purchase tax act previously but hadn’t appreciated that point. Out of interest, are you the ex FTT Judge Richard Thomas?

Yes