Here’s Oxfam’s press release from earlier this month:

To Oxfam’s credit, they now link to the methodology from the press release:

So a company has made a “windfall profit” – and gets taxed at 90% – if its 2021-2022 average profit is 10% above the 2017-2020 average profit.

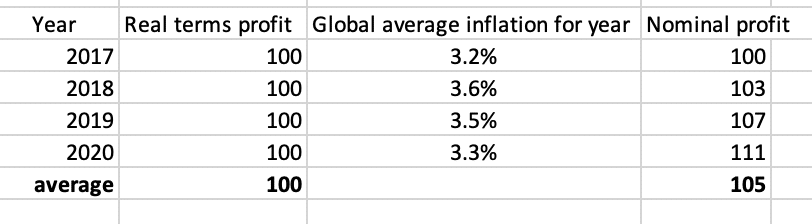

Here’s a simple math question: how fast would a company’s profitability have to grow over those six years before it has a 10% profit increase, and therefore a “windfall”?

Let’s start by assuming no real terms profitability growth at all, and see what happens. Starting with $100 profit in 2017, and using a very simple model that just uprates each year’s profit by global average inflation in the previous year:

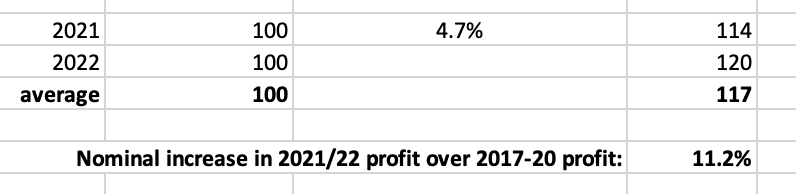

Now let’s keep going, and see where zero real terms profitability growth takes us in 2021-22:

That 11.2% increase is, in Oxfam’s terms, a windfall – and the 90% tax applies (because they only use nominal figures). But in real terms, there’s been no profit increase at all.

So the answer to the simple math question is: Oxfam forgot about inflation, and compounding. so its methodology will always consider a company to have a windfall unless its profit has shrunk in real terms. They didn’t actually find 722 multinationals that had made a windfall; they found 722 multinationals whose profits hadn’t fallen in real terms (or at least hadn’t fallen much).

I wrote to Oxfam pointing this out and received a disappointing response (full copy here) which justifies reporting profits in nominal figures (which is fine, indeed commonplace), but doesn’t justify using nominal figures/ignoring inflation to calculate “windfalls”. I don’t think it can reasonably be defended.

I don’t think this was intentional. Oxfam used to write thoughtful pieces about the role of taxation in development. Now they just throw out endless identikit windfall tax and wealth tax proposals; how and whether such proposals could actually be implemented doesn’t seem terribly important to them anymore.

It’s a shame. Oxfam have considerable resources and a large research team. If they turned back to serious tax policy they could do a lot of good.

3 responses to “Oxfam – taxing a windfall that doesn’t exist”

What profit are we talking about? There are many steps between value added, value added at current prices, pre- and post- tax profits, etc. I can see Oxfam have persuasive publicity in favour of redistribution of benefits from economic activity but this doesn’t do anything for serious improvement of the human lot. Some kind of tax has to be levied in this wonderful, complex, globalized world. Would a slice of gross revenue be simpler and enforceable?

Any suggestion based on firm facts and careful analysis would be welcome.

I don’t understand that at all. What’s wrong with taxing profits?

I think you have it, Dan. Most of these proposals placed by campaign groups are as enmeshed in what I call the Anger Reaction Complex which they believe is wholly confined to the the political right. Getting the Clikz are what they are primarily interested in.

Dear Oxfam, the sources you give for your numbers are reputable sources aimed primarily aimed at smart professional investors (plus Forbes readers). They know about inflation. They discount the nominals for inflation and other stuff and pay (or paid) people like Dan to check it and advise on aspects of investment decisions. So I agree with Dan. Unless you do this your conclusions are meaningless. He is not saying that companies do not make supra-normal profits. He is saying that your methodology mis-identifies them. but Hey! It’s all capitalist breadhead, Dude.

I have transferred my daily adjusted minor irritation from some random oligopolist megacorp to Oxfam. I will fine Oxfam one old unwanted paperback.

Cheers,

A.