Our report on Monday revealed the scheme: it used 10,000 UK companies, supposedly owned by 10,000 Philippine individuals, to claim at least £50m in tax incentives. A central player admits the scheme was fraudulent. On Wednesday published the Giles Goodfellow QC opinion that approved the scheme, and explained why we regarded the opinion as improper.

We now are publishing an earlier opinion from another KC, issued around the time the scheme was created. We believe the opinion is improper, as it proceeds on the basis of stated and unstated assumptions which the KC should have realised were fictional. However, it is less clear to us that this KC could or should have identified that the scheme was fraudulent – we are therefore not publishing the KC’s name (and we don’t believe it can be guessed from the opinion text).

The Goodfellow opinion related to the Contrella scheme. The director behind that scheme admits it was a fraud, and has been financially ruined and disqualified. It is not entirely clear who the commercial party behind the scheme was.

This second KC opinion relates to the MyPSU scheme, which The Guardian convincingly linked to the (now defunct) Anderson Group – and the opinion itself identifies Anderson. It is important to note that this defunct Anderson Group has no connection whatsoever to the current Anderson Group, or the many other businesses called Anderson/Andersen.

The director behind MyPSU, Scott Rooney, has also been disqualified, in highly suspicious circumstances.

The opinion

We are publishing a full copy of the opinion here, with our commentary.

The opinion is remarkably short, and light on technical content. Most of the tax conclusions follow immediately from key assumptions, presented to the KC by the client. Those assumptions are highly questionable.

Implausible stated assumptions

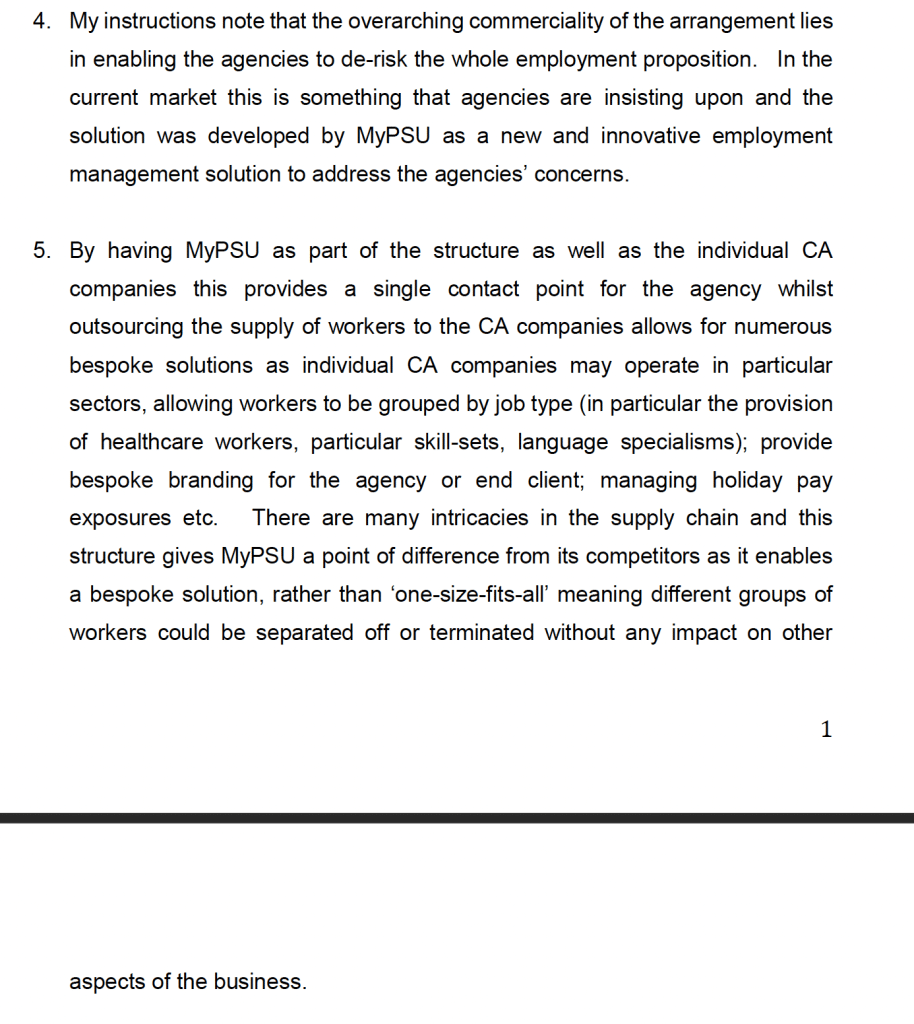

The opinion is in some respects more questionable than the Goodfellow opinion, as it disposes of most of the analysis by accepting a far-fetched claim in the instructions that the structure is commercially motivated.

This is the key section:

This assumption is absolutely key: the structure was commercial because it “enables the agencies to de-risk the whole employment proposition”. That is gobbledegook. There is no purpose or benefit to the structure other than obtaining the employment allowance (and VAT flat rate scheme). Agencies liked it because they shared in some of the economic benefit of this tax avoidance.

The various explanations in paragraph 5 are window-dressing. Recruitment companies had operated for decades with numerous employees in one company. MUCs make management more difficult, not easier.

Essentially all the opinion analysis then follows from this assumption.

It would surely be improper to advise on the basis of instructions that a barrister knows are false. But the KC is an experienced barrister – why did he think these claims were credible?

Once opinions can be given on the basis of false instructions, tax opinions become a game. All difficulties can be assumed away. The opinion becomes of no technical value; it is merely window dressing that enables the parties to say they have a “KC opinion”, and provides a valuable potential defence against HMRC penalties and any attempt at a prosecution for tax evasion.

This was obviously a tax avoidance scheme, and a properly independent KC should have advised on that basis.

Implausible unstated assumptions

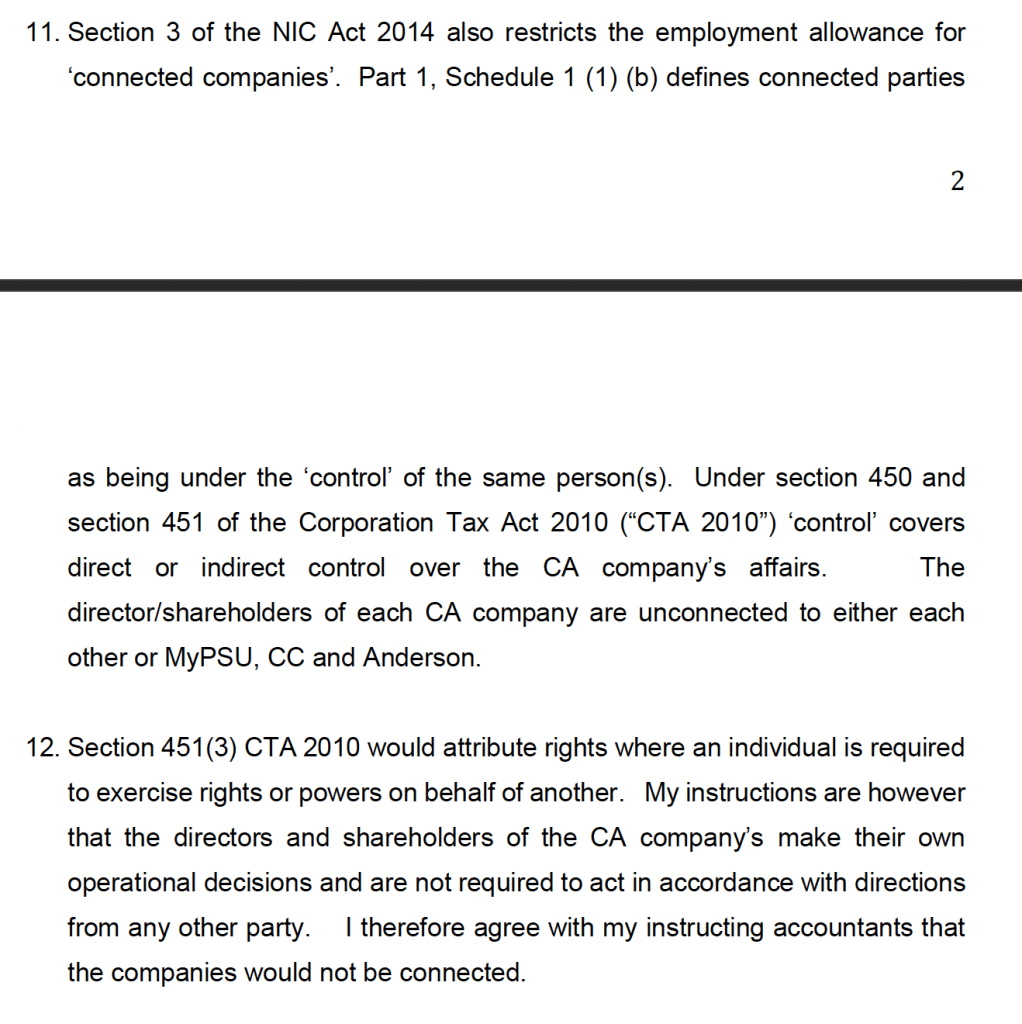

The Giles Goodfellow KC opinion had a lengthy analysis on whether the MUCs were under common control. This opinion disposes of the point in two paragraphs:

This evidences no independent thought by the KC. How did he think the companies would be coordinated? How did he think the shareholders/directors would be recruited and managed? We do not know if the KC was aware of the agent arrangement and director/shareholder portal. But he should have realised that the tax benefit of the structure for any one MUC was much too small to justify independent management activity. Indeed if the MUCs behaved independently then the structure would not work commercially.

The problem is that the coordination required for the structure to be commercially viable presents a “control” problem. Mr Goodfellow was aware of that (although we think his analysis was clearly wrong). This KC missed the point entirely, making an implicit assumption there would be no control as a matter of fact. He was wrong – and he should have known better.

Were there fraud “red flags”?

That is not clear. The opinion does not have several of the “red flag” elements present in the Goodfellow opinion:

- It is not clear from the opinion that the KC knew the plan was to appoint Philippine directors of the MUCs. Mr Goodfellow did know that. He also knew that an effect of this was to make it impossible in practice for HMRC to recover unpaid tax from those directors.

- Mr Goodfellow answered a series of questions about what happens if HMRC assess the MUCs for tax and it is not paid, and whether the tax can then be collected from those behind the structure. This KC does not appear to have been asked these questions.

- Mr Goodfellow advised that (in essence) the existence of his opinion provided a defence against any allegation of criminal tax evasion. This opinion contains no such advice.

- Mr Goodfellow knew that a bank account would be held for the benefit of a large number of companies with unknown Philippine individuals as directors, and he should have realised that the bank would not be informed.

We believe that Mr Goodfellow could and should have identified (from the information before him) that the structure would end up fraudulent. It is not clear to us that this KC could have done so.

We are therefore not naming this KC. Any authorities, barristers or researchers who wish to know his name, or have a copy of the original PDF opinion, should contact us; under the right circumstances, we will provide these details, subject to appropriate confidentiality agreements.

The problem with KC opinions

This opinion and the Goodfellow opinion had consequences. They enabled promoters to sell the scheme to people (read the comments of David Smith here). The schemes ended up fraudulent, costing the UK many tens of millions of pounds in lost tax. There are plausible estimates that, since 2014, all the various mini-umbrella schemes have cost the UK over £1bn.

However, there is currently no consequence for KCs issuing opinions based on highly dubious factual assumptions, and highly questionable legal theories – even when the KCs could and should have suspected fraud. In normal commercial transactions, lawyers have strong incentives to provide prudent and correct advice. In these tax avoidance schemes, they do not. That has to change – we need incentives and proper accountability.

Perhaps the Bar Standards Board will take action (and we will be referring both opinions). But we think the real answer is to create a statutory standard for tax advice.

Thanks to Simon Goodley at the Guardian for the original reporting on this, and Richard Smith, Gillian Schonrock and Graham Barrow for their amazing investigative work (again noting that they draw no legal conclusions; the legal conclusions are the sole responsibility of Tax Policy Associates Ltd).

Thanks to R, P, T, C, M and B for their help with our tax analysis, to K for assistance with the confidential information and privilege elements, to Michael Gomulka for a useful discussion of the barristers’ Code of Conduct, and to A for finding the reference to umbrella schemes in recent tax tribunal data. Thanks to JK for her insight on umbrella companies

5 responses to “The other KC opinion behind the outrageous £50m tax scheme (part 3 of a series)”

My spidey senses started tingling when I read the bit about the national minumum wage in the opinion. But lets get to that in a bit.

My assumption of the “overarching commerciality” thing is that (i) the end client doesn’t want the hassle of employing people directly, (ii) the agency doesn’t want this hassle either, and (iii) the derisking is done by the umbrella company employing the individuals. That makes commercial sense to me and is normal. But I don’t see that going a stage further and splitting the employment of the individuals over a large number of companies that (they hope) qualify for the maximum possible amount of employment allowance is commercial. Having non-resident directors (if that is the case here) makes the system even harder to operate in practice (e.g. what happens if a non-resident director goes AWOL?).

I’ve skimmed through the opinion and saw this (my emphasis): “For both the purposes of the employment allowance *** and the national minimum wage legislation *** it is important that the CA, rather than MyPSU, is the true employer”.

NMW would apply no matter whether the CA or MyPSU was the true employer. So is counsel saying something like (in my words): “”For both the purposes [of paying individuals less than] … the national minimum wage legislation it is important that the CA, rather than MyPSU, is the true employer [since when they are paid less than the NMW you guys won’t be liable to pay the short-fall]”?

I could see counsel saying “don’t forget NMW” or “don’t forget NMW will be due even if the directors are non-UK resident”. That’s a helpful reminder. But to say that “it is important” for the NMW legislation that MyPSU is not the true employer really makes me wonder.

I know that HMRC changed the law from April 2014 to stop schemes circumventing the NMW (the salaried member rules were designed to stop “night club bouncers” and “cherry-pickers” being paid less than the NMW by making them members of an LLP – the consultation said: “At one end of the scale, groups of low paid workers who would normally be regarded as employees are being taken on as LLP members as a condition for their obtaining work”). Was this a way of getting around the NMW too?

Oh, and I’ve you captcha – way more fun that most.

Those are great points. Thank you. I’ll add a note in the opinion commentary.

And sorry about the captcha – it infuriates me as well, but I haven’t found a better solution..

Is there a parallel universe located near Gray’s Inn in which these KC’s opinions are intended to operate? Because they seem divorced from the real world of the labour market and interacting with HMRC on a regular basis.

The one de-risking element I could see is to avoid employment protection legislation.

Great point. “This isn’t tax avoidance because it’s employment protection avoidance” would make for an interesting time in court.