We’ve been asked a few times to analyse the revenue impact of imposing 20% VAT on private schools. We’ve declined, because it’s a complicated piece of work which probably requires a large team with economic and educational expertise – the actual tax element is relatively small and straightforward.

UPDATE 11 JULY: this article is now out of date – the IFS has published a serious piece of research on the subject

A think tank, EDSK, published a paper today looking at this point. Unfortunately, they have not actually undertaken their own analysis, just made some simple calculations based upon previously published figures. The problem is that those figures are, in our view are highly questionable, and perhaps useless. Hence this is a case of “garbage in, garbage out”, and we would caution against taking any figures in the report seriously.

For the same reason, we would caution against taking any of the various figures floating around seriously, unless and until a full analysis is undertaken.

Credit to EDSK – their paper readily admits its own flaws, right at the end – key effects were not taken into account. But these are significant issues which can’t just be ignored:

The questionable figures

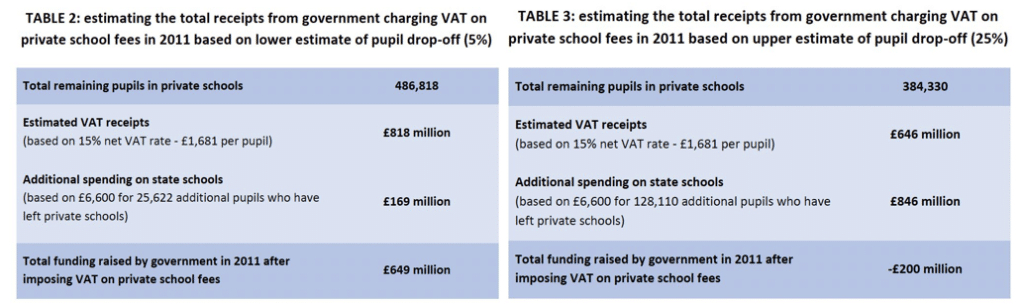

Any estimate of the revenue impact rests upon a key question: what percentage of children would leave private schools if VAT was imposed? The paper uses two previous estimates: 5% and 25%. It treats them as higher and lower upper bound estimates:

But the 5% and 25% figures shouldn’t be treated so seriously.

The 5% figure comes from the 2019 Labour Party manifesto. It took a price elasticity estimate from an IFS analysis which looked at the impact of changes in school fees on the rate of children going to private schools. Then the Labour Party simply applied the elasticity to a 20% price increase.

This was not a good approach. The IFS paper looks like a serious piece of work, but it looked at much smaller prices than 20%, and occurring over a long period. So it is likely incorrect to assume the IFS elasticity holds for an immediate 20% VAT increase, and this error surely means that the Labour Party figure was understated. On the other hand, the IFS found price sensitivity only at entry points – ages 7, 11, 13, and so it’s not correct to simply apply this elasticity to all private school pupils. That would tend to over-state the effect. Taken together, these effects render the 5% estimate of limited and perhaps no use.

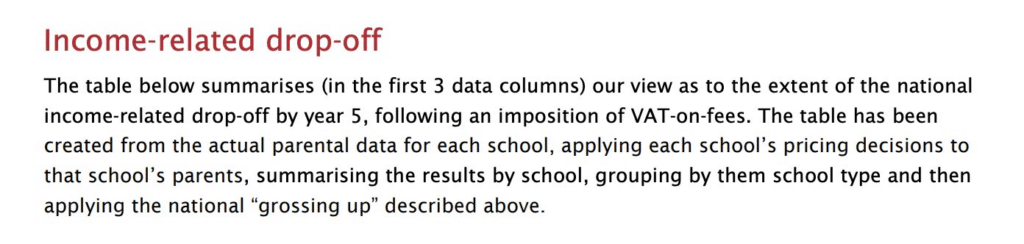

The 25% figure comes from a slightly mysterious survey of heads and parents at 21 schools by a consultancy engaged by the Independent Schools Council. The mystery being that details of the methodology are scant and, even in principle, surveying parents and headteachers in a mere 21 schools seems unlikely to reveal much about what would actually happen across the country if school fees increased. The likelihood of conscious and unconscious bias is obvious:

Exactly how the calculations were carried out is not revealed in the paper, but there is no evidence of any statistical analysis, and results are presented to two decimal points without any discussion of statistical error (or indeed even a single mention of any statistical tools).

Hence we would regard the 25% figure as meaningless. We don’t think EDSK should have taken them as upper/lower bound estimates, or even used them at all.

How would an actual analysis be undertaken?

Having spoken to a variety of economic and education policy experts, we believe a proper analysis would look something like this:

- Dividing independent schools into different size/wealth/location categories. Then for each, analyse sample accounts & model the extent to which private school will absorb additional costs, reducing profit (for for-profit schools), cutting back on capital expenditure, etc.

- Where the VAT leads to increased fees for a category of school, model the effect on different categories of parents – different income levels, overseas vs local etc. Simple uniform elasticity calculations don’t really cut it, because there are so many different types of schools and children/parents. One would also need to model parents switching from more expensive to less expensive private schools. This would all be very challenging, and none of the experts we spoke to were sure how it would be done (albeit these were brief conversations).

- To complicate things further, Some schools may increase bursaries/i.e. cross-subsidise from wealthier parents to poorer. So impact may be greatest on “middle income” parents (relatively speaking). And/or some schools may scrap bursaries, making the impact greatest on lower income parents. Predicting the outcome here may not be straightforward.

- That gives the response for different types of parent in different types of school. But then it’s necessary to adjust for a significant time factor. Expect a small immediate effect (i.e. few parents would pull their children out mid-year). Then a somewhat larger effect for pupils moving into next academic year but, per the IFS paper, by far the greatest impact on new pupils starting at the school at 7, 11, 13. There would plausibly be an initial time-lag to reflect the fact that parents may have missed the deadline to start in the state sector.

- Then model how the schools would respond to the pupils leaving. This would be a sudden shock for the sector, and we could see dramatic reactions. Some schools could become uneconomic after losing just a few pupils, and shut down. Other schools could change their model to enable them to reduce fees. In the longer term, new schools could start up operating a lower-cost model. It’s often said that, in the 1970s, Eton had contingency plans to move to Ireland – that must be another possibility, although query if the schools most able to afford so dramatic a move would economically need to?

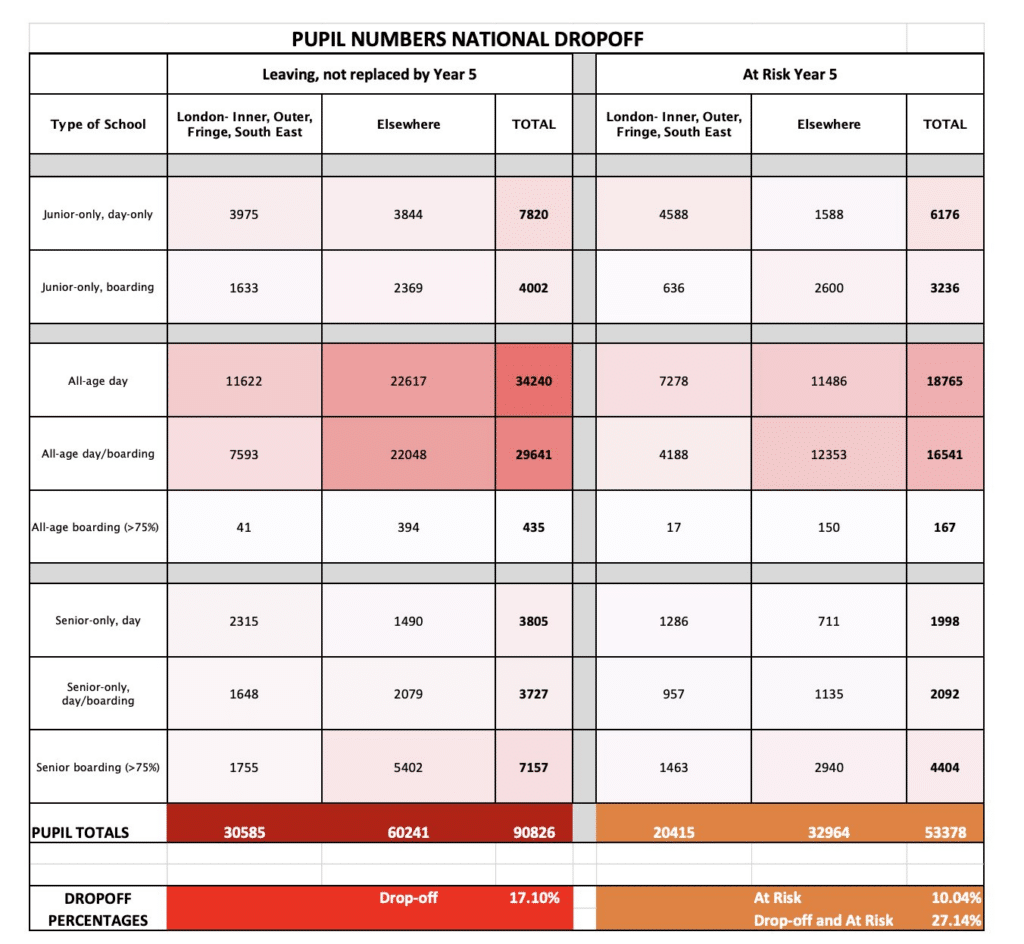

- Then find the cost for educating each category of pupil that leaves and joins the state system. The EDSK paper does this by pulling out a calculator and dividing (1) the total cost of state education system by (2) number of pupils:

- That’s not reflective of the actual cost. The extent to which local state schools have capacity to absorb leaving pupils with/without significant additional expenditure will vary hugely area-to-area and school-to-school. One plausible story: the incremental costs of absorbing a few pupils are very small, particularly given long-term demographic trends (fewer young people). Another plausible story: private schools thrive in areas with less choice of state school, and those schools are already packed, so there simply isn’t space to absorb the influx of new pupils, and new buildings/capital expenditure would be required. Then the costs would be large. Which is it? Or is it something else? Without actually undertaking a detailed analysis of private schools, state schools and demographics, this is just more guesswork.

- Then, in case the above is insufficiently challenging, there are the wider third and fourth order effects. What do people who leave the private sector do with the saved £? Spend it on tutors? on holidays? Save it? Reduce debt? What happens to teachers who leave private schools? All has economic and tax effects. Perhaps this enhances the tax yield, because parents now buy more VATable stuff. Or perhaps not.

So the figures in this paper are just guesses multiplied by guesses. The difficult and uncertainty analysis that is omitted is where the truth actually lies. To be fair, the paper really admits that at the end.

How much would the 20% VAT be offset by recovering VATable expenses?

Something the report gets right is that the cost for a private school of imposing 20% VAT would not be 20%.

At present, private schools suffer VAT on their expenses (“input VAT”) but, unlike a normal VATable business, they recover little or none of this.

In other words, a normal business buys a £1,000 computer. They pay £1,000 plus £200 VAT, but can recover the VAT. Net cost: £1,000. But for a private school, the net cost would be £1,200 (or almost £1,200).

Once school fees become VATable then the private school would be treated in the same way as a normal business. That computer would cost £1,000 net.

The extent of this effect depends on the proportion of a school’s costs that are currently VATable. The majority of the costs will be staff wages, and there’s no VAT on that. The Independent Schools Association estimated the net impact would be 15% – we haven’t seen underlying data supporting this, and so the figure should be used with caution. But it feels in the right ballpark.

What about the technical VAT concerns raised in the paper?

Here we are able to comment fairly definitively. The concerns raised are weak and in some cases incorrect.

This section suggests that there is doubt as to how “closely related” supplies such as boarding accommodation will be taxed.

But that’s straightforwardly wrong. If education becomes VATable then closely related supplies will too. No further legislation would be required.

Then the report suggests there are obvious ways schools could escape the tax:

Trying to avoid the VAT by pushing boarding into a charity would be (naive) VAT avoidance, with no realistic prospect of success.

The paper mentions other potential complications, like the capital goods scheme and people paying years of fees up-front. But these are obvious points that I’d expect any legislation to deal with.

Our conclusion

Technically it is straightforward to impose VAT on private schools. Things only get difficult if it’s done in such a way as to create arbitrary boundaries. For example, imposing VAT on schools charging (say) £8k/year or more would create a powerful incentive for a school currently charging (e.g.) £10k to reduce its fees to £7,999 and then pile on a series of individual charges for books, trips, etc.

Fortunately, politicians never create VAT rules with arbitrary boundaries, so there is nothing to worry about here.

However at present we simply do not know what the revenue impact would be. We don’t know how schools would respond, and the extent to which the tax would be passed-on. We don’t know how parents would respond, and the extent to which pupils would leave the private sector. We don’t know how the State sector would absorb those pupils who would leave the private sector.

We’d therefore suggest disregarding the figures in the EDSK report, and the other figures sometimes referred to. At least until someone actually does the difficult job of undertaking a proper analysis.

More generally, when there’s limited or bad data, the temptation is to use it anyway, because it’s “all we have”. That temptation should be resisted. Garbage in, garbage out.

24 responses to “Don’t (for now) believe anything you read about the revenue impact of charging VAT on private schools”

Dan – I think it would be helpful for you to provide an analysis of the IFS report as, although thorough, I feel there are problems with it.

The IFS have made a very bizarre assumption in their report

“ If parents chose to reduce demand for private schooling, then demand for other goods and services would rise, thereby increasing VAT revenues from those other goods and services. Indeed, if we assume constant consumer expenditure and an effective VAT rate of 15% on other goods and services, then while reduced demand for private schooling would reduce VAT from private schools, it would have zero effect on overall VAT revenues.”

Why would parents who chose to spend their money on private education decide to spend the money they “save” by their child being forced out of education on VATable goods and services?

The obvious immediate ways to spend that money are on

1. Moving close to a top state school or

2. Private tuition

1. Is hard to do. Yes it raises SDLT, but not at 15%. And is just makes the top state schools elitist

2. Labour could make this VATable I guess,

There is no way that the parents of children who send them to private school are going to start spending their money on cars/holidays etc. The vast majority of these people having given up exactly those things for their children’s education.

Another issue the IFS does not address is that for many, many schools the loss of a handful of pupils will make it unsustainable. They would have to raise fees even further, resulting in more parents not being able to afford them. The impact of multiple private schools closing down has not been taking into account. And it won’t be Eton closing down.

Finally, what also seems totally bizarre in the whole argument is that education is investment. It’s not consumption. Even the EU knew that and so if it weren’t for Brexit, this move would be illegal. This makes it obvious that Labour’s reasons for doing this are nothing other than political and have no basis in economic/tax theory or equity

I can’t really comment on those IFS points, as I don’t have exercise. But I would add that EU law isn’t much impediment to scrapping the VAT exemption, as it permits the exemption to be conditioned so narrowly as to be effectively scrapped.

According to VAT Notice 701/30:

“If school, higher or further education is being provided for a charge (see paragraph 3.1), the VAT consequences are for an eligible body (see section 4):

* the education provided is exempt

* any ‘closely-related’ goods or services provided are exempt

* the sales of other goods or services are taxed in the normal way”

So an independent fee-paying school (per 3.1) providing “education” is exempt. Note that para 3.1 also includes

* non-maintained special schools

* universities

* institutions teaching EFL

So any change would need very careful guidance to avoid fallout hitting other educational institutions.

At least, that’s my reading of it.

One likely result that doesn’t get discussed.. The VAT change will push the privates to strongly increase recruitment of foreign students. The schools will increasingly be a UK export business of credentials for wealthy non-Uk students. If that is Labour’s solution to UK inequality.. then u get what u wish for, BTW: in this case the schools stay open, VAT is collected, and the Corbyn dream of closing Privates is changed into a repurposing of the Privates. But does this help UK education? The wealthy non-uk will thank u though…

As alluded to by a previous commenter, the charitable status of many private schools may be of more importance than the VAT issue. Traditionally the provision of education has always been considered a charitable purpose. However what if “the provision of education in return for payment” was specifically excluded from being a charitable activity. This would not prevent private schools creating connected charities to pay the fees for pupils whose parents’ would not otherwise be able to afford them but it would prevent fee paying pupils from receiving any benefit from such charities. It would also place the definition of charitable activity more in line with a common understanding. Not many people would see subsidising general fees at Eton or Harrow as having any recognisable charitable purpose or benefit.

Perhaps the Labour Party should look at the definition of charitable purposes more closely before considering imposing VAT on School fees. Obviously if the provision of Education (for payment) was no longer considered a charitable purpose then most closely related activities would fall with it.

An excellent paper. Good to see an appreciation of the impact of statistics and behavioural issues which make it impossible to reduce an issue such as this to a simple mathematical problem.

I found the comment about Eton’s 1970s back-up plan to move to Ireland interesting. You may not know but fee-paying schools in Ireland benefit from government-paid teachers albeit at a higher pupil/teacher ratio than non-fee paying schools. A move to Ireland would dramatically reduce the cost base irrespective of VAT!

This advice note from Farrers whose clients include various private schools discusses options for disaggregating fees with not just boarding but welfare services potentially chargeable at a different rate. I realise it will all come down to legislation.

https://www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/vat-on-school-fees-qa/

I think there is a typo. Change

What do people who leave the state sector do with the saved £? Spend it on tutors? on holidays? Save it? Reduce debt? What happens to teachers who leave private schools?

To

What do people who leave the private sector do with the saved £? Spend it on tutors? on holidays? Save it? Reduce debt? What happens to teachers who leave private schools?

thank you!

If the imposition of VAT leads to falling student numbers and a number of closures of private schools, won’t the overall tax take also fall given the laying off of staff from those schools – eg reduced income tax and NICs, lower VAT as those people cut back on spending etc?

maybe, and that’s the kind of difficult third/fourth order question we refer to – it would need to be counterbalanced against the overall economic and tax effect of whatever it is that parents do with the money that used to go on fees.

Good article. Maybe the better question is to ask for the analysis which Labour has done on the effect of their proposal / what assumptions they have made / how reliable they are / and how their £1.6 billion figure is arrived at.

Great article.

I wonder that with all the unknowns mentioned the above would be to start taxing at a realtivy small level, say 5%, letting it run for say 2 years. Then reviewing actual hard data to see likely impacts of further increases?

I totally get that this is a slow burn imposition (short term politics gets in the way)

Thoughts?

Sadly I fear VAT changes never work this way…

Whether I agree in principle or not, but bringing into VAT at reduced rate (5% as suggested) you also bring in full recovery of input tax so possibly very minimal financial impact. To do otherwise means creating something like IPT and a whole new set of rules (please no, we have complicated our tax system enough already).

This is a very good point.

Superb analysis on all levels Dan. Do we know where Labour gets their figure as to how much would be raised if they changed the VAT rules to add VAT to private school fees?

(I understand that a number of schools for special needs pupils are also run privately (all be it I assume as charities) and might be worthy of exemption from any new rules intended to hit those who choose to pay private school fees more generally)

I’m not sure, but I’m guessing it’s based on the probably wrong 5% figure…

Schools would be able to reduce their fees before adding VAT as currently an amount of their fees include their running costs with vat included. When they can claim input tax their running costs become net of VAT and therefore this could be removed from the net cost. Not a massive saving but surely somewhere between 2-5%. Those schools that just add 20% onto current fees wold actudd as lily be making higher profit margins.

There is one more complication you have not considered.

Private schools offer bursaries for talented pupils who can’t afford the fees. Assume, for arguments sake, that 1/6 of the total fees a school receives pre awarding bursaries is awarded in bursaries. This means the total spent of bursaries equals the VAT that would be charged on all non bursary pupils fees.

Perhaps the parents who can currently afford the fees when VAT isn’t charge will feel that the school should stop awarding bursaries and use those savings to reduce the fees so that the VAT inclusive price is the same as the old VAT exempt price? I doubt they will be feeling particularly charitable.

So charging VAT on private school fees could lead to the removal of bursaries. Well done Labour, you’ve just made private schools more elitist.

“assume 1/6th funds bursaries”

“assume they stop all bursaries”

draw conclusions on invented assumptions.

Re-read the article and try to grasp the main point perhaps?

The article is about how complicated the issue is

I’m adding one more complication to it not mentioned in the article.

Put it another way. Private schools are perfectly within their rights to stop giving bursaries and use the money saved to offset the VAT increase.

The assumptions are explicitly stated as assumptions to illustrate a point. The first can be proved or disproved. The second is can only be observed after the fact but is not unreasonable. But whatever the proportion of fees funded by bursaries is, it would still be at risk of being used to offset the vat charged

No need to be rude, is there? Not sure why you felt the need to be

Please let’s all assume everyone is writing in good faith and steer away from rudeness.

The potential impact on bursaries is absolutely another unknown, which could go in either direction – I’ve added this to the piece.

> Private schools are perfectly within their rights to stop giving bursaries and use the money saved to offset the VAT increase.

That might be so for for-profit schools. But many (I would think the vast majority of?) private schools are charities. Abolishing their charitable status is a different reform from imposing VAT on fees, and not Labour policy. If most schools were still charities, they would still have an obligation to demonstrate public benefit, not just benefiting their paying customers, whether through bursaries or other measures (such as state schools using their playing facilities). Most would probably be happy about that (because they would still avoid paying business rates). But even if they were unhappy, it would be unprecedented for them to lose their charitable status without specific provision in the legislation.