I keep going back to this Daily Mail story. And, in particular:

How could that happen? How did Mr Duff end up with only £8,000? Indeed how come one postmaster applied for only £15.75 compensation? I didn’t forget to add “thousand” or “million” – the Post Office revealed to me1See below, and the Post Office’s response to allegation number 2 that they received one application for £15.75 compensation. That indicates a very serious problem with the application process.

This article answers that question. Our conclusion: the Post Office has adopted a strategy to minimise compensation for the worst miscarriage of justice in British history. It does that by minimising the initial claim postmasters are making. The Post Office can then point to all the procedures in place to ensure claims are handled fairly – but the unfairness happened right at the start.

Here’s how.

The background

Between 2000 and 20172I have previously written that this was between 2000 and 2013, but I have now spoken to postmasters who faced false allegations of theft as late as 2017, the Post Office falsely accused thousands of postmasters of theft. Some went to prison. Many had their assets seized and their reputations shredded. Marriages and livelihoods were destroyed, and at least 61 have now died, never receiving an apology or recompense. These prosecutions were on the basis of financial discrepancies reported by a computer accounting system called Horizon. The Post Office knew from the start that there were serious problems with the Horizon system, but covered it up, and proceeded with aggressive prosecutions based on unreliable data. It’s beyond shocking, and there should be criminal prosecutions of those responsible.

The Post Office then spent years fighting compensation claims in the courts, using every trick in the book to draw things out as long as possible – even a completely meritless application for a judge to recuse himself on the basis he was biased, which the Court of Appeal described as “without substance”, “fatally flawed” and “absurd”.

Now, finally – ten years after the Post Office almost certainly knew 3Although important people at the Post Office surely knew well before 2013, albeit that the details of “who knew what when” remain unclear that it had wronged these people, it is paying compensation – but in a way that guarantees the wronged postmasters receive derisory sums. This article focuses on the “historical shortfall scheme” (HSS), which compensates postmasters who were not actually convicted of theft, but who were accused of theft, lost their jobs, threatened with prosecution, and forced to repay cash “shortfalls” which in fact were entirely fictitious. There are about 2,500 HSS claims. The average settlement payment so far is only £32,0004The HSS scheme doesn’t cover the postmasters who were wrongly convicted, or the 555 postmasters who claimed under the group litigation order (GLO) – these two groups overlap, but there are likely others who haven’t claimed under any scheme. So the total number of affected postmasters is unknown, but certainly over 3,000

The Post Office say this about the HSS claim process:

I would invite anyone to read the below and then return to this paragraph, and decide for themselves how “simple and user friendly” the scheme is, and how fair and reasonable it is for the Post Office to not cover the legal costs of applying.

There are eight elements of the HSS scheme that in my view amount to a strategy to minimise the initial HSS claims. In other circumstances, I would willingly accept that this was a series of good faith mistakes; but given the history here, I don’t think we can assume good faith.

Here are the eight:

1. Force postmasters (mostly in their 70s and 80s) to go through a complex legal process.

The Post Office could have proactively investigated what had happened, identified and interviewed the people it wronged, and proposed full and fair compensation. After all, it’s the Post Office that required postmasters to repay the phoney “shortfalls” – it surely has at least some data that it could be using to estimate the compensation due, and “pre-complete” forms for postmasters.

But instead, the postmasters are required to complete a lengthy and very legal form, with the Post Office providing absolutely nothing in the way of information or assistance. Even where the Post Office writes to a postmaster saying they identified an issue that may have caused a shortfall, they make no attempt to pre-populate the form with that issue.

I have heard (but do not know for sure) that the Post Office’s systems and recordkeeping were such a disaster that it in fact has little useful data. If so, it is outrageous that the Post Office expects elderly postmasters to have better recordkeeping than a large corporate, and – if they don’t – that this reduces the compensation they receive.

I put this point to the Post Office. Their reply is as follows:

This is all irrelevant, as it’s about the process after postmasters send in claims. None of it is about the claims themselves. The forms are lengthy and complex, and the key elements (dates, amounts of “shortfalls” repaid) should be in the possession of the Post Office. The onus should not be on the memory of elderly postmasters. The fact it is ensures that claims are for far less than they should be. Nothing in the later processes can fix that initial injustice.

2. Ensure the postmasters don’t receive legal advice when they complete the form

The HSS claim form is in reality a complicated legal claim, and nobody should be completing it without detailed legal advice.

The form itself is fourteen pages, plus eligibility criteria, terms of reference, explanatory notes to the terms of reference, seven pages of consequential loss guidance, and six pages of Q&A. I was a senior partner in one of the largest law firms in the world, and I personally wouldn’t complete the form myself – specialist advice is essential.

That legal advice will need to consider all the facts specific to the individual’s treatment by the Post Office, and the financial, health and reputational consequences over the subsequent years/decades. I understand from discussions with experienced lawyers that, for all but the simplest cases, this would require at least a week’s work by a couple of experienced claimant lawyers, so ballpark fees of £10,000.

Few postmasters could afford anything like that. So how much is the Post Office covering?

Zero.

The Post Office provides no cover for legal costs in completing the form. None. It doesn’t even suggest they should obtain legal advice.

Postmasters are being asked to assert their legal rights, and their legal claims for compensation, without legal advice. The intention was that this would be an informal process for which legal advice would not be necessary. However, that is not remotely how it has worked out.

After the Post Office receives the form, it will send the postmaster a settlement offer. At that point the Post Office will cover some legal costs. But it’s too late – the offer has been framed by the form, and the postmaster received no legal advice in completing the form. And only 10% of postmasters took legal advice even at that late point.5The source for this is that, as of 4 April, 1,924 settlements had been entered into, of which the Post Office had covered legal fees of only 198 (see our FOIA correspondence, linked here). Given the age and limited resources of most of the postmasters, it is reasonable to take from these figures that around 90% of the postmasters had no legal representation.

So aged and vulnerable postmasters applying for compensation are required to complete lengthy and complex legal documentation without legal advice.

Here is the Post Office’s response. They say that applying for the scheme is straightforward. Postmasters disagree, and I think most people (lawyers or laypeople) would share that view.

If I was the Post Office, and someone had submitted a claim for £15.75, I would have thought something was very seriously wrong with the claims process.

All of this amounts to conduct by the Post Office’s lawyers which took unfair advantage of unrepresented individuals, contrary to Solicitors Regulation Authority guidance. I will be referring it to the SRA tomorrow.

3. Write the form to prevent claims for damage to reputation

That complicated form seems designed to limit compensation to financial loss – principally loss of earnings, and the fake accounting “shortfalls” which postmasters were required to repay the Post Office if they wanted to avoid prosecution.

Any lawyer – I think any right-minded person – would say that financial loss is the least of it. Stress, suffering, damage to reputation – all of these should be compensated for. But the form goes out of its way to stop this.

Claimants are surely entitled to compensation for damage to their reputation. In many cases that was significant – everyone in the village where they lived and worked became convinced that the postmaster was a thief, with many postmasters forced to move.

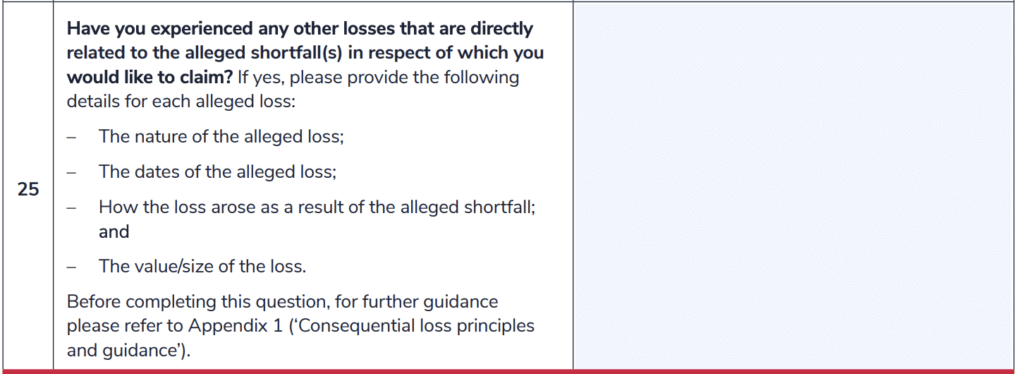

But the design of the form means that claimants are unlikely to realise they can claim for this. Here’s the relevant box:

A lawyer would know this is referring to consequential loss, and would think (amongst other things) about damage to reputation. I doubt many 80-year-old postmasters would do that.

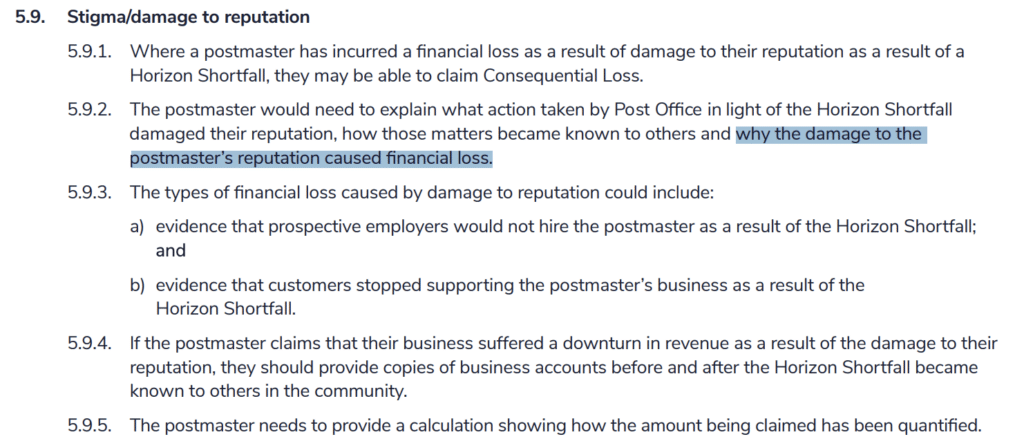

But I suppose a particularly assiduous postmaster might go into the detail of Appendix 1, where we see an acknowledgement that damage to reputation can be included…

… but only where it causes financial loss – which is notoriously hard to quantify.

I paused when I read this, as I wasn’t aware of a legal principle that a person could recover for damage to reputation only where it causes financial loss. I called a few much-more-qualified lawyer contacts. Their answer: there is no such legal principle. The Post Office invented it, to minimise compensation claims.6See the helpful summary set out by Warby J in Barron v Vines, paragraph 21.

I put this point to the Post Office. Their response:

But that is absolutely not what the Post Office’s own guidance says. It says: “Where a postmaster has incurred a financial loss as a result of damage to their reputation, they may be able to claim… The Postmaster would need to explain… why the damage to the postmaster’s reputation caused financial loss”. This is a statement that damage to reputation can only be claimed where a financial loss is incurred, and that is absolutely a misrepresentation of the legal position.

So even if a layperson goes deep into the small print, they won’t realise that they are entitled to compensation for damage to reputation which goes beyond mere financial loss. They have been misled by the Post Office, and that will mean they end up claiming for much less than they should.

Of course, this issue would be spotted by a competent lawyer, but the Post Office ensured that the form would always be completed by an unadvised layperson. So a postmaster would, almost inevitably, claim less compensation than he or she is due.

This is, therefore, conduct by the Post Office’s lawyers which failed to uphold the rule of law, took (once more) unfair advantage of unrepresented individuals and was misleading, contrary to Principle 1 and paragraphs 1.2 and 1.4 of the Code of Conduct for Solicitors. I will be including this in my SRA referral tomorrow.

4. Write the form to prevent exemplary damages claims

When a wrongdoer causes harm intentionally, recklessly, or with gross negligence, then a court can award “punitive” or “exemplary” damages. This seems a model case where such damages would be awarded – so where on the HSS form is the box for a claimant to assert exemplary damages? Where is that mentioned in the Appendix?

Nowhere.

Both of these omissions would be spotted by a competent lawyer; but are unlikely to be spotted by a layperson. And the Post Office ensured that the form would always be completed by an unadvised layperson. So a postmaster would, almost inevitably, claim less compensation than he or she is due.

This is how the Post Office responded:

Again, this doesn’t address the point – the Post Office’s own form, and (lack of) guidance means that unrepresented postmasters will not make these claims.

And the Post Office appear to be saying that punitive damages have only been offered in malicious prosecution cases, and perhaps not even all of those. That cannot be right.

I would suggest exemplary damages should be the rule, not the exception. It seems beyond doubt that the Post Office did act either intentionally, recklessly or with gross negligence (even if at this point we cannot be sure which of these it was).

This is again conduct by the Post Office’s lawyers which failed to uphold the rule of law, took unfair advantage of unrepresented individuals and was misleading – and I’ll be referring it to the SRA.

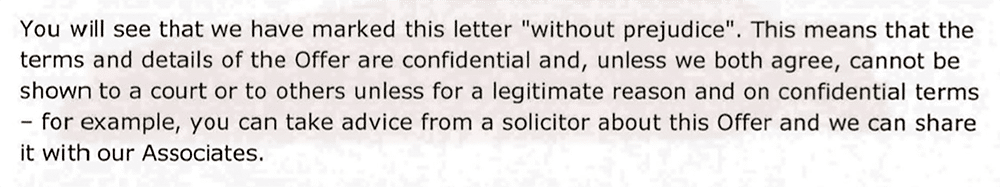

5. Intimidate postmasters into silence, to stop them discussing their settlement offers with each other, friends, family, or the media

As already reported by us and The Times, each postmaster receiving an HSS offer was warned by the Post Office that legally they were not permitted to mention the compensation terms to anyone. This had consequences. They weren’t able to compare compensation terms with each other. They weren’t able to speak to family or friends (who might have suggested they speak to a lawyer). And they weren’t able to go public about the way they were being treated.

This was the key paragraph in each of the offers:

It’s not true. Postmasters were completely free to show their offers to friends, family and the media. We’ve written more about this here, and referred the Post Office’s legal team to the Solicitors Regulation Authority.

The Post Office refused to respond to this point, saying:

This was, yet again, conduct which took advantage of unrepresented individuals. It was also contrary to specific SRA guidance on Conduct in Disputes and the linked Warning Notice on SLAPPs, regarding sending correspondence with restrictive labels where there are no good legal grounds for doing so. I have already referred it to the SRA.

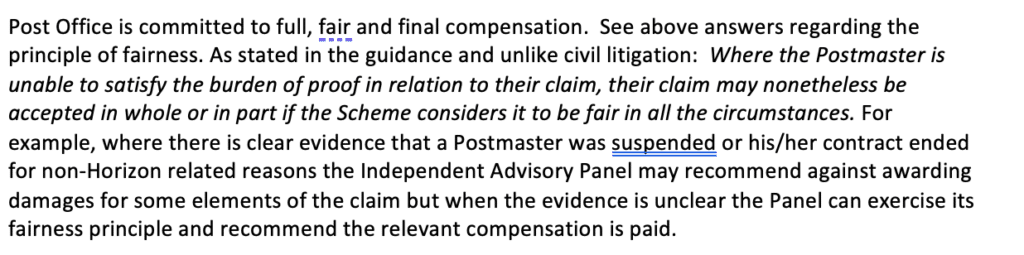

6. Run every possible argument to minimise payouts

The Post Office’s litigation strategy in the 2010s was described by the Court of Appeal as evidencing a “desire to take every point, regardless of quality or consequences”. The Post Office has never apologised for that approach – and seems to be continuing it.

What I’m hearing from postmasters is that the Post Office is running every possible argument to minimise its payouts:

- responding to claims for loss of earnings by arguing that the Post Office would have shut down the Post Office in question under its “transformation programme”, so compensation is limited to the 26 week notice the Post Office typically gives. In strict legal terms that it is a legitimate argument, but (1) it is inconsistent with the informal approach the Post Office should be taking, (2) the Post Office is not running a proper counter-factual but simply asserting the argument, even in cases where the transformation programme would not have applied.

- minimising all payouts for non-financial loss – for example offering £15k to a postmaster who had a stroke as a result of the stress of the Post Office’s false allegations. Indeed it seems that payouts for stress and inconvenience under the HSS rarely, and perhaps never, exceed £15,000.

- responded to postmasters who entered bankruptcy by arguing that the bankruptcy was caused by other factors (whilst providing no evidence of what those other factors might be)

The Post Office appears to be completely ignoring Sir Wyn’s initial finding that “normal negotiating tactics often found in hard-fought litigation in the courts should have no place in the administration of any of the schemes for compensation”.

The Post Office’s response to me does not address the key point here – that the Post Office is running aggressive arguments to minimise payouts:

Where it runs these arguments against unrepresented postmasters – and, remember, 90% of postmasters are unrepresented, the Post Office is in my view taking advantage of unrepresented individuals. I will be drawing the SRA’s attention to this as well.

7. Provide a token amount to cover a lawyer reviewing the settlement

Once the postmaster sends the form to the Post Office, the Post Office responds with a draft settlement agreement, and the postmaster is invited to sign it. At that point, the Post Office will pay for the postmaster to engage a lawyer.

It’s too late. The advice should have been right at the start, to enable the postmaster to construct their claim in a sensible manner, and work out how much tax is due.

And the Post Office is paying an amount which won’t begin to pay for a lawyer actually looking at the fundamentals of the claim. In a Freedom of Information Act response, the Post Office confirmed to me they have paid 1,924 HSS settlements totalling £62m, but in only 198 cases did they cover legal fees, amounting to £217k (i.e. an average of £1,100 each).7Apparently the Post Office pays £400 for small claims and £1,200 for larger claims.

£1,200 of legal advice (for the few people receiving it) would realistically cover a “sense check” of whether the settlement terms themselves are reasonable. It will not cover an assessment of whether the right amount of compensation is being paid.

So this is a fig leaf which enables the Post Office to tell the world it is paying postmasters to receive legal advice, without taking the consequences of postmasters actually receiving legal advice (i.e. having to pay out the compensation that it realistically should be paying).

Back in August 2022, Sir Wyn’s initial report said that reasonable legal fees should be paid where the Post Office’s initial HSS offer was rejected by a postmaster. The evidence suggests that didn’t happen between August 2022 and April 2023, when a large number of settlements were agreed.

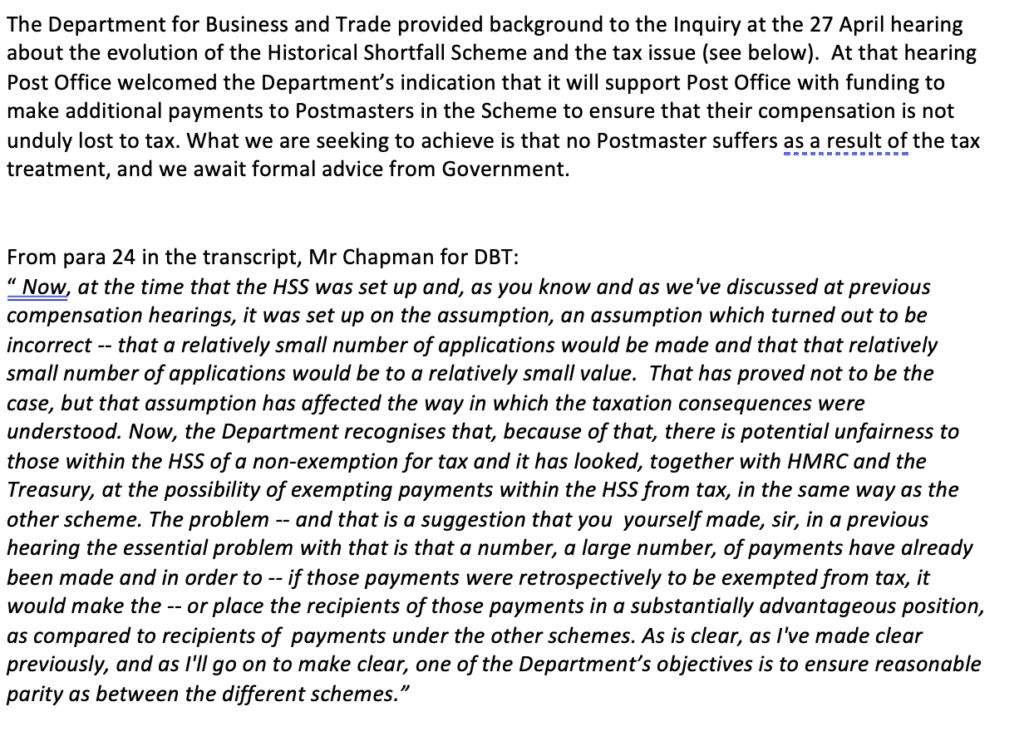

8. Make no attempt to compensate the claimants for tax

UPDATE: as of 19 June 2023, it looks very much like this has now been solved. But the question remains: why did the Post Office put the postmasters in this position?

The Post Office made no attempt to assist the postmasters’ tax position, and didn’t adjust the compensation upwards to reflect tax. So postmasters have ended up losing far too much of their compensation in tax – in some cases up to half. And I fear some will end up falling into default with HMRC.

Many people åssumed this mess must have been because the Post Office didn’t receive proper tax advice on the impact of compensation on postmasters. But the Post Office has now confirmed to me, in another Freedom of Information Act response, that they themselves did receive tax advice from a law firm on the tax position of HSS claimants.8They’re refusing to provide me with that advice; given the overriding public interest, I will be appealing.

These problems could have been avoided if the Post Office had paid for claimants to receive tax advice, covering the terms of the settlement, its consequences, and completion of their subsequent self assessment forms. They didn’t. Out of 1,920 settlements, the Post Office paid for postmasters to receive tax advice on precisely two, and a miserly £500 apiece.

The Government is committed to fixing this – but may be unable to avoid complexity for HMRC and postmasters. All of which is down to the Post Office’s failure. I asked the Post Office why this happened, and why they still weren’t funding tax advice for postmasters – they gave me an irrelevant answer, which dodges both these questions:

If the Post Office did indeed receive tax legal advice which indicated that the Postmasters were being put in an unfortunate position, and it did not relay that to unrepresented Postmasters when making them an offer, then that again is a serious breach of SRA Rules and Principles.

What should happen now?

The HSS compensation scheme isn’t fit for purpose, and has become just one more entry in the sordid list of Post Office failures and obfuscations.

Ideally, it would be replaced, but it’s too late for that – out of 2,400 original applications only 23 are awaiting offers, and 200-300 have pending offers. Time is running out for many of the postmasters, and we can’t have more months and years of delay.

So I would let the scheme let it run its course, but establish a quango empowered to review every single Post Office compensation payment, from all the different schemes/settlements, and make whatever additional payments to the postmasters as it thinks is fair and just under all the circumstances. The usual paradigm of legal claims would be replaced with an informal inquisitorial process. It would, of course, be funded by the Post Office (although the Post Office is insolvent, and so ultimately every £ would come from the Government).

And what about the individuals responsible?

It remains to be seen whether individuals will be held to account for having destroyed thousands of lives.

When Sir Wyn’s Inquiry is complete, and his findings published, I hope prosecutions follow against key individuals for perjury and/or perverting the course of justice.

I also hope we see Solicitors Regulation Authority proceedings against the Post Office’s internal and external lawyers. That means the lawyers involved in the original prosecutions, and the lawyers involved in sustaining meritless litigation for years (including those making a hopeless recusal application which they must have known would fail, and was no more than a cynical delaying tactic).

It should also mean SRA proceedings against those lawyers who constructed a compensation process which has the effect of taking advantage of vulnerable people who the Post Office knew were not legally advised.

The compensation process itself is a scandal, and there should be consequences for those involved.

Thanks to Anthony Armitage for his expertise on the SRA Standards, to P and F for their input on the tort law elements of the above, and all the postmasters who have contacted me with their practical experience of the HSS process. And thanks to Tom Witherow and the Daily Mail for their original story which inspired/infuriated me to look into the Post Office scandal in more detail. Finally to the Times, for ensuring that the continuing horrors of the Post Office scandal are making regular headlines.

-

1See below, and the Post Office’s response to allegation number 2

-

2I have previously written that this was between 2000 and 2013, but I have now spoken to postmasters who faced false allegations of theft as late as 2017

-

3Although important people at the Post Office surely knew well before 2013, albeit that the details of “who knew what when” remain unclear

-

4The HSS scheme doesn’t cover the postmasters who were wrongly convicted, or the 555 postmasters who claimed under the group litigation order (GLO) – these two groups overlap, but there are likely others who haven’t claimed under any scheme. So the total number of affected postmasters is unknown, but certainly over 3,000

-

5The source for this is that, as of 4 April, 1,924 settlements had been entered into, of which the Post Office had covered legal fees of only 198 (see our FOIA correspondence, linked here). Given the age and limited resources of most of the postmasters, it is reasonable to take from these figures that around 90% of the postmasters had no legal representation.

-

6See the helpful summary set out by Warby J in Barron v Vines, paragraph 21.

-

7Apparently the Post Office pays £400 for small claims and £1,200 for larger claims.

-

8They’re refusing to provide me with that advice; given the overriding public interest, I will be appealing

Comment Policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – it’s better if the discussion is focussed on the key technical and policy issues. I will also delete comments which are purely political in nature.

11 responses to “Eight reasons why the Post Office compensation scheme is a scandal”

I can’t understand how the postmasters had to pay the shortfall, as they were allegedly thieving from the post office. It has now being proven that the post office stole from them. Why are they not entitled to the over payments back, as well as compensation? People lost their homes and jobs needlessly! This is without even considering health, stress and family. None of which can be rectified, but the financial losses can and should be.

I am familiar with the pressure that partners in service firms (including lawyers and accountants etc) are under in order to achieve their revenue targets let alone gain further promotion and I have no doubt that the personal interests of the various ‘advisors’ in this morally bankrupt process were manipulated by their clients to achieve the required result. People in these positions have very little moral fibre – a past colleague of mine once said to me as we put together a large proposal – why let the truth get in the way of a good sale?

This summarises what I think of ‘advisors’ in this debacle

The reason I feel so strongly about this is that I read recently that Post Office (or, as my father – a head postmaster for many years who stayed with The Post Office all his working life used to refer to it – The Post Office) said that they have not had to pay out as much as they had budgeted for on this matter because fewer than expected had claimed and those who had, had clearly not claimed enough. Can somebody please tell me how we have got into a situation where corporate organisations have become so devoid of any sense of morality and integrity for example the PPI refund scandal with the banking system and the Big Pharma fentanyl scandal and now Post Office.

The onus should NOT be on wronged customers to have to prove that they are due compensation, the organisation has all the records/data needed whatever they claim to the contrary and the onus should be on them to identify the problem, communicate it to the customer/employee and make an offer of compensation which can be assessed without prejudice by the plaintiff and/or their lawyer.

Post Office used to be known for their honesty and integrity which in turn elicited a loyal conscientious workforce – how things have changed, my father would turn in his grave if he could see how morally bankrupt this organisation has become – the latest set of corporate cowboys to join the gang – despicable people with not an ounce of conscience or integrity.

But they all keep getting away with it because they have the money to fund clever lawyers who exploit those who do not even understand how they can be/are/continue to be manipulated – not only that but I understand that the ordinary tax payer is funding a significant amount of the Post Office’s costs associated with these spurious prolonged drawn out proceedings – it’s a disgrace – our justice system and democratic governance should be ashamed of themselves – but, hang on, that assumes they actually have a conscience

Thanks for this. I was aware of the general issues but not the legal ones, and my outrage continues.

As an Accountant rather than a lawyer it stuck me for the first time that in fact there must have been a massive fraud going on at the Post Office HQ because if all these people are innocent (and it seems obvious [except to the PO management] that most of them must be) then combined they injected a huge amount of extra cash into the PO coffers – which must have been removed elsewhere in the system for the books to balance in reality (vs the fan tasty of the IT system). Who were the auditors ? Where were/are they ? I’m not clear why we are not hearing about this aspect.

funnily enough someone was asking me the other day about the accounting treatment of the “shortfalls”, the payments to correct them, and the ultimate compensation payments. I don’t know the answer.

Although I’m aware of the situation, I’ve not followed this closely, but it does sound like a class action lawsuit would be appropriate here?

I’m only a layman and I’m not legally qualified in anyway but I’ve followed the story and it makes my blood boil! That people can be treated in this way is appalling.

Did the Post Office perdue Fujitsu for their part in this?

If so, did they get any money out of them?

If so how much and where did it go?

Could the Legal Ombudsman investigate with a view to claiming money back?

Great article, thanks for taking an interest in this. There is a role for the SRA here, both regarding the original wrongful prosecutions plus the abusively-designed so-called compensation scheme.

The law firms involved, and the specific partners responsible, need to be investigated and punished. That should include crippling, solvency-undermining fines for the former, and fines and strike-offs for the latter. Done sufficiently robustly, this should set an example for the future. It’s impossible to play whack-a-mole with every dishonest individual and organisation in society, but (a) we can shape systemic incentives; and (b) that has the potential to determine future outcomes. Doing so at the regulatory level has the potential to achieve systemic change. As Charlie Munger warned, ‘Show me the incentive, I will show you the outcome’. The example here is perhaps NDAs: after the Weinstein NDA became a cause célèbre, the SDT prosecuted the A&O partner responsible, and articulated stringent new rules. The substance of that prosecution was arguable on the merits, but the Post Office scandal is far more clear cut in terms of both the wrongful prosecutions and the compensation scheme.

Professor Richard Moorhead has written superbly on the topic of what he (charitably in my view – I’d be far more accusatory) calls client/lawyer ‘mutual irresponsibility’:

“A striking feature of many corporate or other scandals is how organisations and their lawyers construct a system of mutually assured irresponsibility. Some of this is done artfully, some without even thinking about it. The problem often, subtly or unsubtly, comes down to this: the client says they did what they did because the lawyer advised them it was legal and the lawyer says they were mere advisers following instructions. Lawyers, too often, and often incorrectly in my view, say they bear no moral or professional responsibility for the acts of clients that flow from their advice. It boils down to this: the client says, my lawyer said I could do it; and the lawyer says, that doesn’t mean I said they should do it. Or, It’s the law’s fault, not mine. Or, bloody law professors don’t understand what commercially savvy legal advisers need to do to make a living these days.

There are two convenient features of this: (1) no one is to blame when the proverbial hits the fan and (2) the factual accuracy of who did what and why lies hidden behind legal professional privilege. Sometimes, as appears to be the case in the Levitt report, when the veil is lifted, the lawyer is seen to be telling the client exactly what the client should do and doing so on shaky legal grounds.

We can see an example of mutually assured irresponsibility in the Post Office case in this letter from Paula Vennells, former CEO to the Post Office, to the BEIS Select Committee in 2020. In this letter she seeks to diffuse responsibility for the Post Office scandal far and wide. Part of that diffusion involves her relying on legal advice… [continues]”

https://lawyerwatch.wordpress.com/2021/09/18/mutually-assured-irresponsibility-an-example-from-the-post-office.

SRA and BSB guidelines are meant to limit lawyers’ ability to run improper arguments of fraud, or similarly serious allegations. In practice however, (a) some clients will sack law firms which are insufficiently aggressive; (b) partners will sack counsel who refuse to run whatever points they insist upon; and so (c) ultimately, SRA and BSB guidelines are toothless and impotent – Munger’s incentive/outcome problem noted above. (As you’ll infer, I’m commenting on this from personal observations in large law firms).

The issues arise even without all three parties (client/solicitor/barrister) being equally ruthless and mendacious. For example, the pressure on newly-appointed salary partners in large firms to justify their promotion – and to claw their way up the pole to equity partner – must be immense. The partner’s self-interest is the plainly to do whatever necessary to make their business case for equity partner. That includes generating ££££ of revenue and keeping/making happy clients. It’s plain to see how ethics gets thrown out of the window.

The Post Office debacle has been truly shameful, but even though the SRA are sniffing around the topic, it is unclear that (a) they/the SDT will take powerful enough action; (b) the BSB are famously lax, so counsel may emerge unscathed (Google ‘Hendron BSB’ for simply one example, and consider how in contrast the SRA sometimes prosecutes trivialities); and (c) whether the opportunity will be taken to put teeth into the currently routinely-ignored rules SRA and BSB on running improper prosecutions/arguments/claims which risk destroying people’s lives.

My understanding is that WBD were responsible for the wrongful prosecutions, and HSF were responsible for the abusively-designed compensation scheme. In my view, the SDT should prosecute both firms and all of the implicated partners. If even a fraction of what has been openly reported is true, the resultant financial penalties should be so severe that the survival of the firms is fatally undermined. The collapse of two firms would be a clarion call to the rest of the profession that ethics matter, and to do better in future. Presently, any such incentives are notably only by their absence.

I have heard a few comments to the effect that sums of £500-£1,100 for subpostmasters to receive legal advice may seem very high rather than miserly.

This is an understandable perspective but to provide some background (and apologies to Dan as I know he has touched on some of these in previous articles).

i) These are complicated and difficult legal claims that the subpostmasters have. The history of these goes back up to 15-20 years so there is a lot of documentation and evidence to trawl through. A proper assessment of these claims is likely to take many many hours. Accounting advice may be needed to establish the nature and amount of loss suffered. In that context, the amounts offered are derisory. £10k’s worth of work is not unreasonable at all.

ii) The structure of the scheme to only offer a contribution to legal costs AFTER a draft compensation figure has been proposed by the Post Office is particularly cynical. The message is – take our first offer or you will be out of pocket. There is no reason to do this other than to pressure a claimant into settling early and for an undervalue. As a solicitor I find this morally reprehensible.

iii) The Post Office themselves have hired City lawyers on hourly rates of several hundred pounds an hour, amounting to over £100m over the years (paid for and underwritten by the public purse). In comparison, many of the solicitors working for subpostmasters in reviewing these settlements are not the “fatcat lawyers” that some will imagine – rather, they will be doing this work either pro bono or for fixed fees at a breakeven price or possibly even a loss.

Thanks, Chris. One way to think about it is that if you’re expecting £300k compensation (say) then £10k in legal fees doesn’t feel large. Another is that this would be a week’s work by a couple of people. 70 hours x £150/hour = £10k. And that’s a low hourly rate for a lawyer.

Most lay people have no idea about law firm fees. Having worked at a similar firm to HSF in London, fees were broadly as follows:

Associate: £400-600/hour.

Senior associate: £700-800/hour.

Counsel: £900/hour.

Partner: £1,000-1,200/hour.

The problem is that most people in the UK are relatively unskilled and paid accordingly (hence why taxes on London professionals de facto pay for most of the UK). Average weekly earnings across the UK were, for example, £568 per week and £642 per week for April 2021 and May 2023, respectively.*

Here, people’s lack of understanding creates a vulnerability which HSF (who, I understand, designed the compensation scheme) appear to have been very happy to exploit. Let’s hope that (a) the wrong is rectified; and (b) HSF pay a price for it.

*

April 2021: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/averageweeklyearningsingreatbritain/april2021#average-weekly-earnings-data

May 2023: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/averageweeklyearningsingreatbritain/may2023