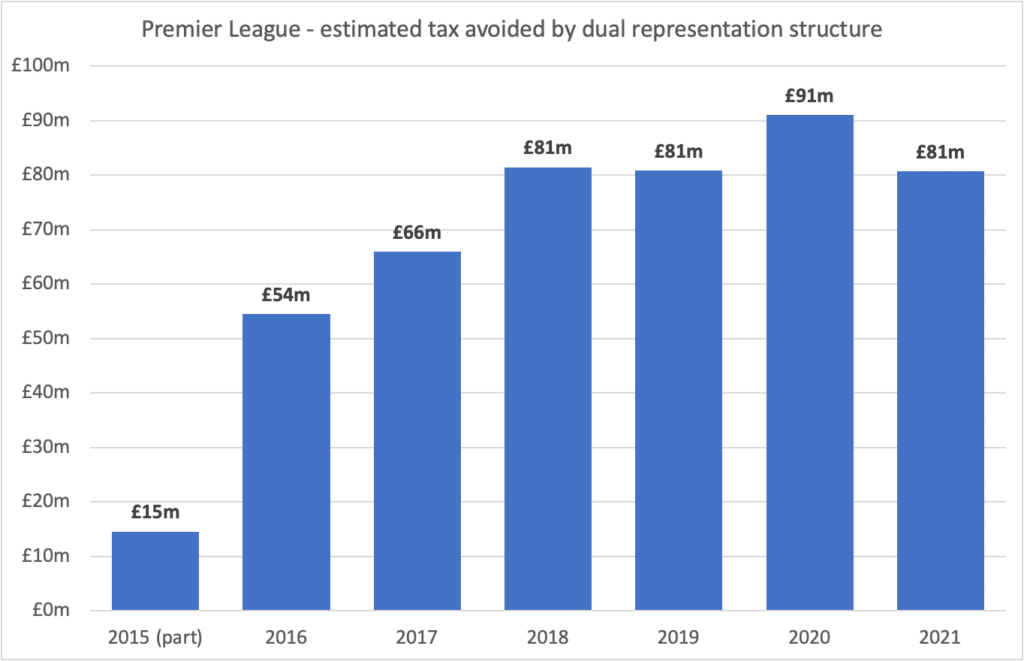

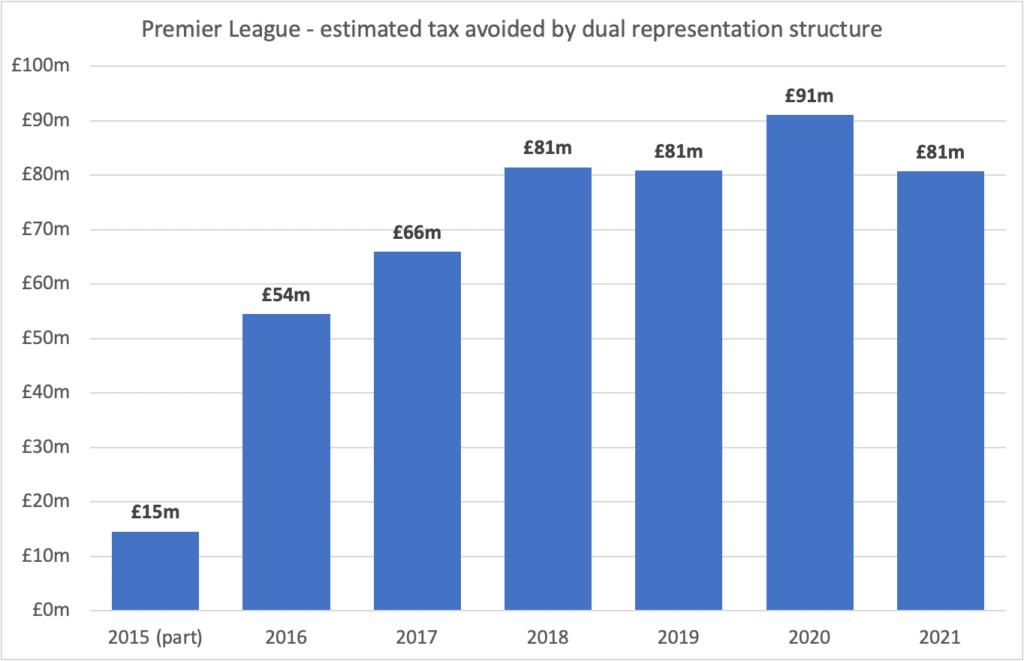

Tax Policy Associates today reveals that Premier League football clubs are avoiding tax on an industrial scale, by artificially structuring their payments to football agents. We estimate it cost £250m in lost tax from 2019-2021, and £470m since 2015.

In our view this is failed tax avoidance – it was never compliant with the law, and HMRC can and should require all the lost tax to be repaid.

There’s extensive BBC Newsnight coverage and analysis here.

Football clubs at all levels are using an artificial tax avoidance scheme to avoid VAT, income tax and national insurance/social security. In the Premier League alone we estimate that this has resulted in £250m of lost tax in the last three years, and £470m of lost tax since 2015:

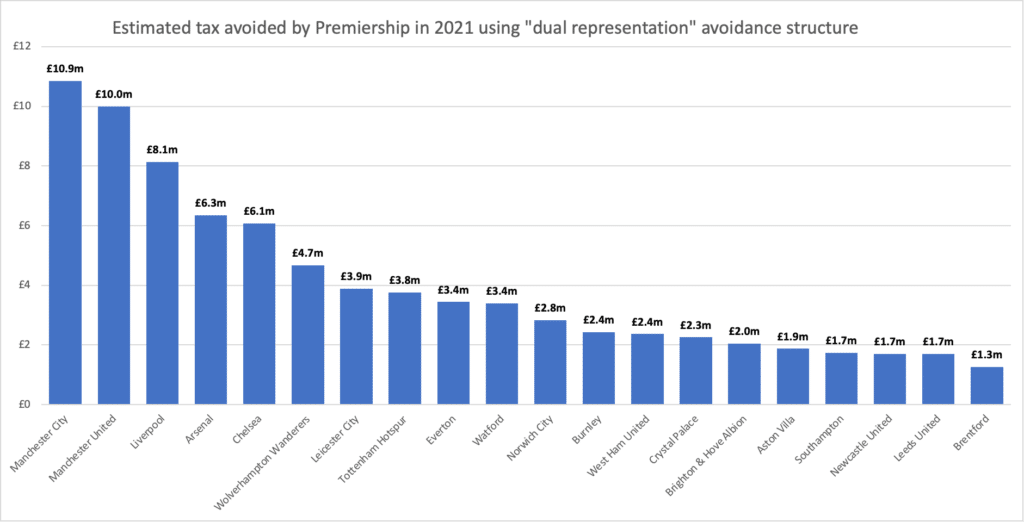

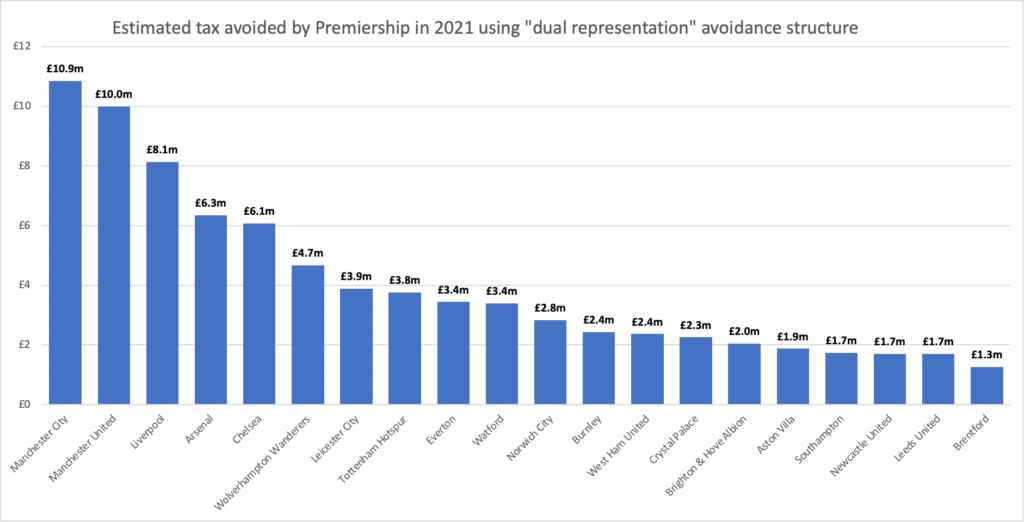

And here’s our estimate for each Premier League club’s tax avoidance in 2021:

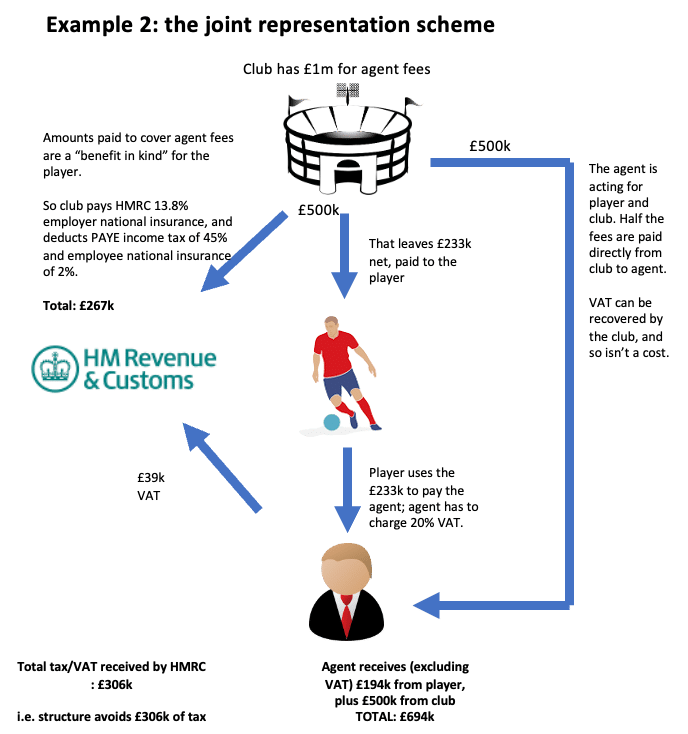

The purpose of the scheme is to avoid employment taxes and VAT on the large commissions paid to football agents. In reality, these agents act for players. But the scheme works by constructing artificial contracts where the agent acts for the club as well as the player – so-called “dual representation contracts”. Half the fees are then paid by the club – even though it is the player who is really benefiting from all (or almost all) of the agent’s work – and these fees escape income tax, national insurance and VAT.

The defence of dual representation contracts by clubs is that “everybody does it”. That is true. But it’s our view that the arrangements are improper – they contravene both the letter and the spirit of the law. This isn’t “legal tax avoidance” – it’s a failure to comply with the law. HMRC should be aggressively challenging it (and we understand that, in least some cases, it already is).

There are potentially serious consequences for football. If HMRC were able to recover all £470m then Premier League clubs would struggle to pay it – the Premier League’s total profits in 2022 were the largest for some time, but still only £479m.

This report explains how the scheme is supposed to work, why it technically fails, and what should be done to stop it

Football agents and fees

Football agents usually act for players. Sometimes the agent is one individual who is close to a particular player and acts for them and nobody else. Sometimes the agent is a business which acts for multiple players. But the role is much the same in either case: connecting the player with clubs, managing contract negotiations, finding sponsorship, and generally advancing the player’s career.

Agents (sometimes called “intermediaries”1The football industry currently prefers to use the term “intermediary”, but in our view it is both clearer and more accurate to use the traditional term “agent”, and that is the term we will use in this report.)) are typically paid by receiving a percentage of their players’ remuneration. In the past this has sometimes led to extraordinarily high payments, with a FIFA report suggesting $3.5bn was paid to agents between 2011 and 2020, and another report estimating $500m in agent fees were paid in 2021 alone (a slight decline on the $650m paid in 2019, probably as a result of Covid).

Of all the tasks undertaken by the agents, the contract negotiations are the most critical, given that the outcome of those negotiations drives remuneration for the player, and therefore the agent.

New FIFA rules were approved in December 2022 capping agent fees at (for large amounts) broadly 6% of the remuneration paid to the player. Given the size of transfer payments, that still equates to very large fees to agents but, whilst the rules are supposed to enter force in October 2023, it is unclear whether that will happen.2It is likely that agents will assert that there are competition law/anti-trust problems with the proposal and, whilst we have no expertise in competition law, that does not seem a frivolous objection.

The usual treatment of agent fees

Everyone who is employed and working in the UK pays income tax and national insurance on their wages. When we hire someone to carry out a service (plumber, lawyer, estate agent, etc) we are not entitled to deduct that cost from our taxes. In other words, we pay almost all service providers on an after-tax basis. In addition, if the service provider is VAT registered, then we usually pay VAT on their fee.

In some cases, it will be the employer who pays the cost of the service. For example, an employer may agree to cover an employee’s personal legal fees. That will usually be a “benefit in kind” with the employee taxed in exactly the same way as if he or she had received the cost of the legal fees as additional salary or bonus. The legal fees will also be subject to VAT, which the employer will not be able to recover (unlike the company’s own legal fees, which will often be recoverable).

So whether an employee engages a service provider directly, or their company does so on their behalf, should make no difference to the tax result.

How should agents and clubs be taxed on agent fees?

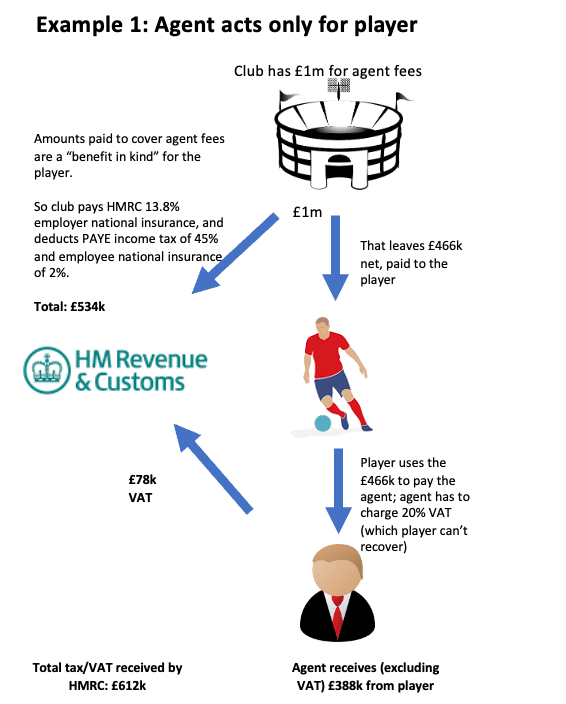

The same principles should apply for clubs and football agents. The agents are hired by the player, represent the player in fee negotiations, and their loyalty is to the player. The player therefore shouldn’t be able to deduct the agent’s fees from his income tax bill, and the player should have to pay 20% VAT on the agent fees.

And, as with the legal fee example above, none of this should change if the football club agrees to pay the agent’s fee – they’re doing so on behalf of the player, and so it’s a benefit in kind. The tax bill ends up the same – income tax, national insurance and VAT on the agent’s fee.

This example shows how it should work, with £1m paid in agent fees. HMRC ends up receiving £612,000 of tax. It would be the same if the club was paying £1m in legal fees or estate agent fees.

The tax avoidance scheme

The scheme

Historically, agents were hired by players, and either paid by players or paid by clubs (with the benefit-in-kind and VAT consequences discussed on the previous page). However, many years ago, some people in the football industry realised they could avoid a significant amount of tax if they wrote all the contracts so the agent purported to be the agent of the football club, not the player.

This had two sizeable tax benefits. First, the club could now pay the agent fee without it being a taxable benefit for the player – saving (at current rates) 45% income tax, 2% employee national insurance, and 13.8% employer national insurance. Second, the club (unlike the player) could recover the 20% VAT the agent will charge on the fee. Add these up, and the total tax saving is equal to 80.8% of the agent fee.

Over time, a degree of caution from advisers meant that this approach was replaced with “dual representation” – the agent supposedly acting for both the player and the club. By 2021, the fees were typically (and, we understand, almost universally) allocated 50-50 as between player and club.3Interestingly, the 50-50 split has now been formalised by FIFA in its new regulations (see Article 12(8)(a). Indeed, at first sight, the regulations seem to incentivise joint representation, because the cap on agent fees will be 3% (rather than 6%) if an agent is acting solely for a player. The reason for this is unclear, but we would speculate that agents and/or clubs lobbied for the rule to give cover to the dual representation tax avoidance scheme. This reduced the total tax saving to (at current rates) 40.4% of the agent fee (i.e., half the benefit compared to if the agent was solely acting for the club).

This second example shows what happens when the 50-50 dual representation avoidance scheme is used. As with the first example, £1m is paid in agent fees – but the effect of the scheme is that HMRC ends up receiving £311,000 less tax.:

Why call this a “tax avoidance scheme”?

A common characteristic of tax avoidance schemes is that an arrangement which would usually have one tax result is structured in a different and artificial way, and claimed therefore to have a different and more favourable tax result. That is exactly what is happening here.

The “dual representation” arrangement is fundamentally artificial. Whatever the contract says, everybody knows the agent isn’t really the agent of the club. The agent is hired by the player, and their principal role is representing the player in negotiations with the club, to extract as a high a price as possible from the club for the player.

There’s an obvious conflict of interest. The player wants to be paid as much as possible. The agent is paid a percentage of the player’s earnings, and so also wants the player to be paid as much as possible. On the other hand, the club wants to pay as little as it can get away with.

It is often asserted that the agent does in fact provide real services for the club. For example, the agent may assist with work permits, and help the player get settled into their new home. However, there are two obvious responses to this. First, these services primarily benefit the player. Second, the value of the services is low, and can’t begin to justify half the fee being allocated to the club.

Are joint representation contracts permitted by the Football Association and FIFA?

The Football Association prohibits an agent from acting for both the player and the club – but with a remarkably wide exemption4see section E of the FA guidance here: https://www.thefa.com/-/media/files/thefaportal/governance-docs/agents/intermediaries/the-fa-working-with-intermediaries-regulations-2020-21.ashx that in fact allows an agent to act for both the player and the club, provided the right boxes are ticked.

FIFA was at one point proposing to end joint representation contracts, but the final version of the rules mirrors the Football Association in having an apparently clear prohibition followed by an extremely wide exception to the prohibition:5See the new regulations, Article 12(8)(a)

A Football Agent may only perform Football Agent Services and Other Services for one party in a Transaction, subject to the sole exception in this article.

a) Permitted dual representation: a Football Agent may perform Football Agent Services and Other Services for an Individual and an Engaging Entity in the same Transaction, provided that prior explicit written consent is given by both Clients.

So triple representation is prohibited, but dual representation has been given the green light.

How much tax is being avoided?

We estimate £470m of tax was avoided in the Premier League between 2015 and 2021:

Looking at 2021 in detail, we estimate that the £81m of tax avoided was split between clubs as follows:

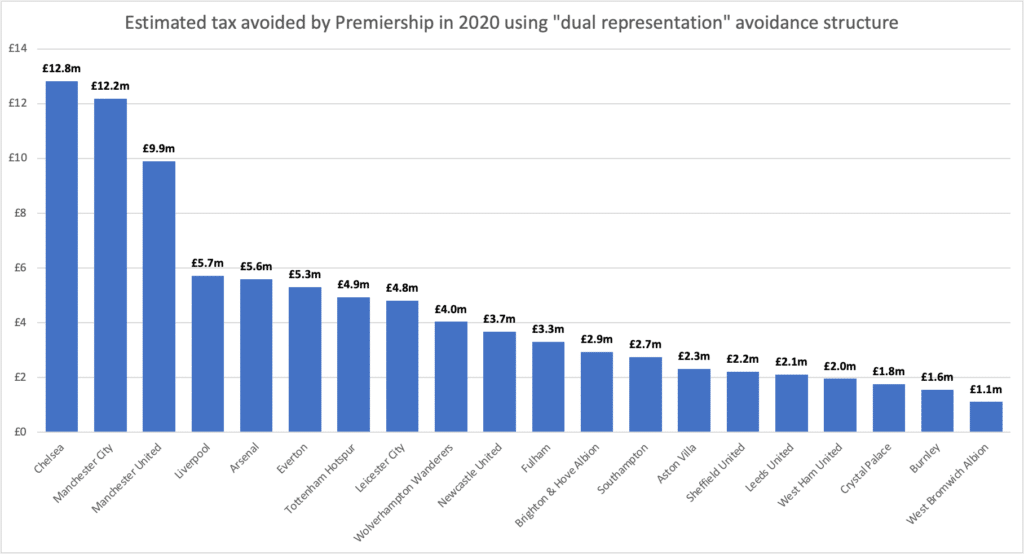

And the £91m avoided in 2020 was split as follows:

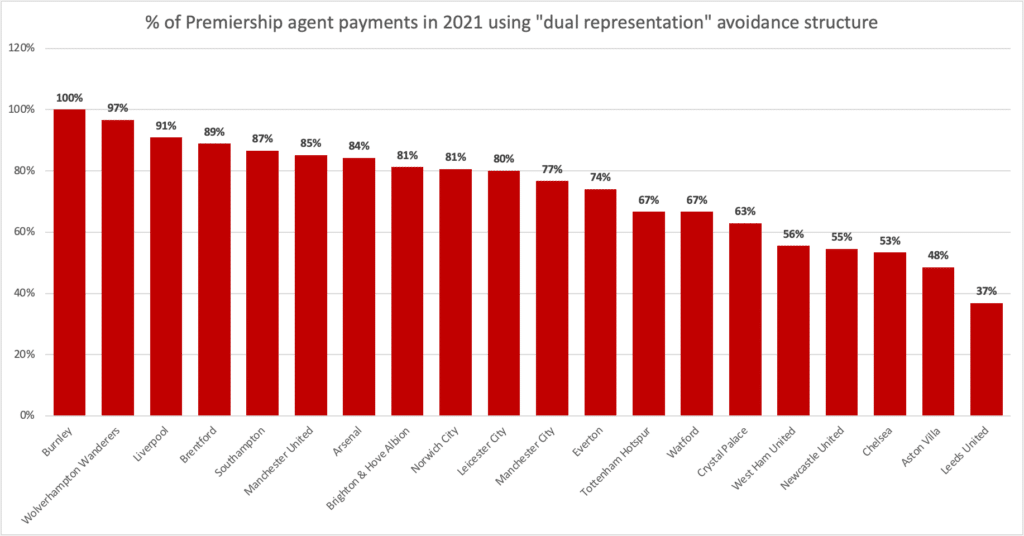

The biggest clubs pay the biggest fees, and so dominate the charts above. However, if we look at the proportion of transactions using the dual agent structure in 2021, it is clear that some clubs use the structure all the time; others are less consistent. Generally, the richest clubs are the most frequent users, but Burnley and Brentford are also heavy users:

What are HMRC doing?

In the 2010s, clubs convinced themselves that there was a “safe harbour” that meant HMRC wouldn’t challenge dual representation structures provided the split was no greater than 50-50. However we don’t believe that is correct – there never was a safe harbour, and HMRC never accepted these arrangements.

HMRC became aware of the urban myth of a “safe harbour”, and issued particularly clear guidance in May 2021 refuting the claim. The guidance says that a 50-50 split cannot be the default position, and has to be carefully justified by reference to the work actually undertaken by the agent for the club, and with detailed records kept. This was in the context of an overall high level of HMRC scrutiny on football and football agents in particular.6See for example https://www.gov.uk/government/news/top-football-agent-scores-12-million-tax-avoidance-own-goal and https://www.mirror.co.uk/sport/football/news/taxman-probing-thousands-football-agents-16228503

HMRC guidance is just an expression of HMRC’s opinion, and is not legally binding. Given the likelihood of a dispute, well-advised taxpayers typically are very cautious before ignoring HMRC guidance. However, it is not uncommon for some taxpayers (and advisers) to follow the letter of the guidance and ignore the spirit. That seems to have happened in this case; we understand from sources in the industry that most clubs still use a 50-50 split (albeit they are more careful to justify it, and create a supportive “paper trail” which purports to demonstrate value being provided to the club).

Perhaps for this reason, there is no evidence of dual representation contracts declining in 2021 – 68% of relevant contracts were dual representation that year, the same as in 2020, and only slightly down on 2019 (when it was 70%)

Part of the problem is the competitive dynamic between clubs – agents will play one off against another, and any club that’s too scrupulous in its tax planning can find itself losing out in the race to hire new talent. This is a common dynamic that drives tax avoidance in many industries, and the solution is public pressure, aggressive enforcement by HMRC, and a change in the law. We discuss this further below.

Another problem is that we understand there is close collaboration between the tax teams at the Premier League clubs. That can create an atmosphere that their tax positions are “too big too fail” – for surely HMRC wouldn’t challenge everyone? In most industries, competition law concerns mean that tax teams in different companies do not coordinate their positions in this way. It is unclear why football is different.

We understand there are several live HMRC enquiries into the use of dual representation structures by Premier League clubs, but the scale of HMRC’s work in this area is not clear.

If HMRC does pursue the structures aggressively, and across several past years, there could be serious financial consequences for the clubs involved. In the worst-case scenario for the clubs, all the tax we identify as having been avoided could be repayable, plus interest and potentially penalties. Whilst there is certainly lots of money in the Premier League, there is very little spare cash available to fund unexpected tax liabilities – total Premier League profits for 2022 were only £479m.

Our view – is the dual representation structure lawful?

Dan Neidle worked as a tax lawyer for 25 years, and was head of UK tax for one of the world’s largest law firms7It is important to note that Dan never advised on the use of dual representation contracts, and so holds no client-confidential information relating to these schemes.. He had particular expertise advising clients who had previously entered into tax/VAT avoidance schemes, or who were exposed to risk as a result of other parties’ use of such schemes.8This is a common commercial problem that tax lawyers are asked to solve, for example where a bank is lending to a business that had might have entered into a tax avoidance scheme, or a company taking over a business in that position. In both cases, the lawyer’s client will want to understand the nature and risks of its counterparty’s tax planning, and whether and how that planning should be conceded and settled with HMRC.

Dan’s view of the dual representation scheme is as follows:

“In my view it is clear that the dual representation schemes do not work. HMRC should challenge current and historic use of dual representation contracts, and in my view HMRC would win.

In relation to income tax and national insurance, modern caselaw has established that these taxes apply realistically to the actual commercial transaction, and not to artfully constructed paperwork.9There is an accessible summary of modern direct tax principles of interpretation in Barclays Mercantile Business Finance Limited (Respondents) v. Mawson (Her Majesty’s Inspector of Taxes (Appellant) – see paragraph 26 here. Realistically, the agent is acting only for the player. The most economically valuable part of the agent’s role, and the basis on which agents are remunerated, is their negotiation of the player’s remuneration. When entering into these negotiations, the agent can only be acting for the payer, and not the club (as otherwise the agent would be negotiating against him or herself). The club may be making the payments, but this is a matter of convenience – the agent is not, in reality, acting for the club (other than for minor ancillary services). Hence, I expect a tribunal would simply apply the income tax and national insurance legislation on the basis that all, or almost all, the payments made by the club to the agent are made on behalf of the player, for services provided by the agent to the player.

In some cases, where the agent in reality provides no services at all to the club, the contractual appointment of the agent by the club might be a sham.10The sham doctrine in Snook v London and West Riding Investments Ltd (available here) is narrow in scope, and requires that parties create a document which appears to HMRC (or other third parties) to do one thing, but actually intend and act in a different way. Hence a typical artificial tax avoidance scheme is not a sham, because the parties do intend to be bound by the documentation. In this case the divergence between reality and documentation means that the potential for a sham cannot be entirely excluded, although it will depend upon the precise facts.

Different civil law-style “abuse” principles apply for VAT (see the Halifax decision), but in this case it is likely that those principles are not necessary, and the correct VAT result will simply follow from a proper analysis of the nature of the services that are actually being provided. In particular, a Tribunal is likely to readily conclude that the supplies by the agent are “made to” the player and not “made to” the club under Article 168 of the VAT Directive11The VAT Directive remains part of UK tax law post-Brexit – that was necessary to avoid the huge amount of uncertainty which would have resulted had it been repealed. and section 24 of the Value Added Tax Act 1994 (and the fact the club is making the payment to the agent is irrelevant). That conclusion is consistent with the Supreme Court judgment in the Airtours case.

The key question for clubs to answer is why they thought it was appropriate to say that half the value provided by agents was provided to clubs, when it’s the players who receive almost all the benefit.

I expect the clubs will say that they have tax advice that the dual representation structures are appropriate. But I understand that advice is usually based upon a critical factual assumption that agents really provide value equal to half of their fees – an assumption that is plainly incorrect. If that’s right, then the advice is worthless, and the clubs should have known that. I would also query whether it was appropriate for advisers to advise on the basis of an assumption that, if they’d thought about, they would have realised was false.

The clubs may have thought they were avoiding tax; but in fact they were simply failing to pay tax that was due, based upon factual assumptions they should have known were false. If they actually knew the assumptions were false, then it is possible that criminal offences were committed.”

Recommendations

We have three key recommendations:

- Parliament should enact specific income tax, national insurance and VAT anti-avoidance rules, to put beyond all doubt that the dual representation schemes do not work. Ministers have previously warned that employment tax avoidance can be countered by retrospective legislation, and that is something that should be considered in this instance. This would save the time and cost of litigating against dozens of clubs across the Premier League and Championships – the result of which is not realistically in doubt.

- Absent retrospective legislation, HMRC should aggressively challenge all the clubs which have historically used joint representation contracts. The starting point should be that little or none of agents’ fees should be allocated to the club – they act solely (or almost solely) for the players. The tax/VAT result should follow straightforwardly from that (with late payment interest also due). Where these contracts were constructed without a reasonable contemporaneous justification for the fees allocated to clubs, penalties should be charged.12Penalties apply where, broadly speaking, a taxpayer has been “careless”. Allocating fees without a reasonable commercial justification in our view falls into that category. HMRC guidance on penalties is here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/penalties-an-overview-for-agents-and-advisers

- Unless full disclosure was provided to HMRC (including the amount of value provided by agents) then HMRC should be able to open a “discovery assessment” and challenge the previous four years of tax returns (and any earlier years which remain “open”13Meaning that an enquiry was opened on this or some unrelated matter for that year, and it has not been resolved). If a failure to provide full disclosure can be said to be “careless” (which is very plausible, particularly where there was not contemporaneous justification for the allocation), HMRC should be able to challenge six years of tax returns. The fictitious nature of the structure also creates the possibility that the 20 year time limit for deliberate loss of tax could apply.

We understand that dual representation contracts are used elsewhere in Europe, and that – as with the UK – the principal purpose is tax avoidance. Other countries’ tax authorities and football associations may wish to consider taking similar steps to those recommended above.

Methodology

Sources of data

In April 2015, FIFA required national football associations to publish statistics on agents (“intermediaries”). Originally it only published the total agent fees paid by each club, and limited data on transactions. However, from 2019, that data also includes whether agents were instructed on a sole or joint basis, which enables the analysis in this paper. The full data is here.

The fee and transaction datasets are separate, so that it is not possible to ascertain the fees paid to any individual agent, or in respect of any individual player.

Approach

We can take the Football Association statistics for 2019, 2020 and 2021 (running from February in each year to the end of January in the next year) and estimate the total tax avoided, using the approach set out below. All the calculations are available in the spreadsheet here.

- For each year 2019-2021, take the FA transactions list and exclude duplicate entries (which we assume are errors). The lists are in the spreadsheet on the “transaction data” tabs for each year.

- Take the FA lists of total fee payments to agents. These are in column B on the “calculations” tab for each year.

- Include only permanent transfers in, loans in, updated contracts, and international loans in (as other transactions are not likely to give rise to material fee payments). These are the “in scope transactions” on the “assumptions” tab. Count the number of payments made by each club on “in scope” transactions – this is column C on the “calculations” tab.

- For each club, calculate the number of those payments which involve joint representations (i.e. where agents were acting for both the player and the club). This is column D on the “calculations” tab. This gives us the percentage of dual representation transactions – column E.

- Assume we can simply apply that percentage to the total agent fees paid by each club (probably resulting in too small a number, because joint representation is likely more common on larger transactions, where more tax is at stake). That gives us the “implied dual representation fees” in column G of the “calculations” tab (which excludes VAT).

- Assume that all the joint representations are 50-50 (the industry standard), and so multiply the total joint representation fees by 50%. The assumption is in cell C4 of the “assumptions” tab.

- Calculate the total rate of tax avoided on this VAT-exclusive agent fee. That will be VAT (20%) plus the top rate of tax (45%) plus the highest rate of employee national insurance (2%) plus the highest rate of employer national insurance (13.8%). That totals 80.8%. This total is in cell C8 on the “assumptions” tab.

- Multiply the VAT-exclusive agent fee allocated to the club (from step 5) by the 50% figure (step 6) by the rate of tax avoided (step 7). This gives the estimate for tax avoided for each club for each year 2019, 2020 and 2021 (column H of the “calculations” tab for each year).

- For the years before 2019, we have agent fee data but no data on the proportion of dual representation contracts. So we proceed on the assumption that the percentage of tax avoided (out of total agent fees) will be broadly the same as in the later years where we do have that data. So a simple pro-rata calculation provides the tax avoidance estimate for 2015 (where we only have the last quarter data), 2016, 2017 and 2018. This is a conservative assumption given that the industry settled on 50% as a supposed “safe harbour” – previously a higher percentage was used. The calculation here is in cells D6-D9 of the “calculation” tab.

- The total tax avoidance estimate sums to £469m (cell D14).

The data also shows a smaller number of cases where the agent is solely acting for the club. Many of these appear to be cases where there are separate contracts between agent and player, and agent and club. We do not know if this is a legitimate arrangement which splits bona fide obligations and fees between player and club, or a tax avoidance arrangement which is effectively the same as a dual representation contract, but splits the contract into two halves. We are conservatively assuming it is the former, and not including any figures from these cases in our estimates of tax avoided.

We are focussing on the Premier League, as its financial predominance means that the amount of tax avoided is disproportionately focussed here. However, “joint representation contracts” are also used in the Championship/lower divisions. Agent fees in the Championship are about 15% of those in the Premier League – so as a rough order of magnitude estimate, we’d expect Championship tax avoidance to be around £70m (i.e. simply calculating 15% of £470m).

An important assumption in our analysis is that fees were allocated between players and clubs 50-50 on all “joint representation” contracts, and that this continued through to 2021 (despite the HMRC warning in the middle of that year). We understand from industry and HMRC sources that this is correct, and that clubs responded to the HMRC warning by being more careful about how they justified the 50-50 split, but not changing it.

If Premier League clubs wish to dispute our use of the 50-50 figure, they can respond by disclosing what the actual dual representation figures are, and we will then immediately update this report.

Response from Premier League clubs

Until the BBC published its story, the Premier League clubs were entirely unresponsive. We contacted the press office of each club for comment late last year, and know that our messages were received – but not a single club replied. BBC Newsnight also contacted the Premier League clubs for comment more recently – again no response was received. Nor did the BBC get a response from the Association of Football Agents.

It is highly unusual for a company which is credibly accused of tax avoidance to fail to provide even a short form response. It is even more unusual for an entire sector to refuse to respond to enquiries. The obvious inference is that the Premier League clubs collectively realise that their position is impossible to defend.

Since the BBC published its report tomorrow, we finally do have a response. Of sorts.

The Association of Football Agents now says it disputes our findings, saying we’re making “fundamental misunderstanding of how the football transfer market works”. Oddly they don’t bother saying what that misunderstanding is. They’ve had months to come up with something better.

The Premier League also provides a non-answer: “We believe that the overall figure suggested here is based on assumptions that do not recognise the individual circumstances of each transaction”. What are those assumptions? How are they wrong? They don’t say. And, again, they’ve had months.

Note what these responses don’t do. They don’t provide a principled justification for dual representation contracts existing at all. They don’t deny that the industry is using 50-50 across the board, despite HMRC guidance saying they shouldn’t.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mike Cowan, Ben Chu and the Newsnight team for helping to develop the story, and to all the tax professionals – solicitors, accountants, barristers and retired HMRC officers, who commented on early drafts of this paper. Particular thanks to Max Schofield for his invaluable comments on the VAT analysis, and to A, F and T for their equally valuable input on the income tax and national insurance analysis. And many thanks to the industry contacts who prompted this investigation, and provided background information on the historic and current use of dual representation contracts. Final thanks, as ever, to J.

Image by DALL-E – “a soccer ball with cash exploding from it, on a grass football pitch, digital art”

-

1The football industry currently prefers to use the term “intermediary”, but in our view it is both clearer and more accurate to use the traditional term “agent”, and that is the term we will use in this report.)

-

2It is likely that agents will assert that there are competition law/anti-trust problems with the proposal and, whilst we have no expertise in competition law, that does not seem a frivolous objection.

-

3Interestingly, the 50-50 split has now been formalised by FIFA in its new regulations (see Article 12(8)(a). Indeed, at first sight, the regulations seem to incentivise joint representation, because the cap on agent fees will be 3% (rather than 6%) if an agent is acting solely for a player. The reason for this is unclear, but we would speculate that agents and/or clubs lobbied for the rule to give cover to the dual representation tax avoidance scheme.

-

4see section E of the FA guidance here: https://www.thefa.com/-/media/files/thefaportal/governance-docs/agents/intermediaries/the-fa-working-with-intermediaries-regulations-2020-21.ashx

-

5See the new regulations, Article 12(8)(a)

- 6

-

7It is important to note that Dan never advised on the use of dual representation contracts, and so holds no client-confidential information relating to these schemes.

-

8This is a common commercial problem that tax lawyers are asked to solve, for example where a bank is lending to a business that had might have entered into a tax avoidance scheme, or a company taking over a business in that position. In both cases, the lawyer’s client will want to understand the nature and risks of its counterparty’s tax planning, and whether and how that planning should be conceded and settled with HMRC.

-

9There is an accessible summary of modern direct tax principles of interpretation in Barclays Mercantile Business Finance Limited (Respondents) v. Mawson (Her Majesty’s Inspector of Taxes (Appellant) – see paragraph 26 here.

-

10The sham doctrine in Snook v London and West Riding Investments Ltd (available here) is narrow in scope, and requires that parties create a document which appears to HMRC (or other third parties) to do one thing, but actually intend and act in a different way. Hence a typical artificial tax avoidance scheme is not a sham, because the parties do intend to be bound by the documentation. In this case the divergence between reality and documentation means that the potential for a sham cannot be entirely excluded, although it will depend upon the precise facts.

-

11The VAT Directive remains part of UK tax law post-Brexit – that was necessary to avoid the huge amount of uncertainty which would have resulted had it been repealed.

-

12Penalties apply where, broadly speaking, a taxpayer has been “careless”. Allocating fees without a reasonable commercial justification in our view falls into that category. HMRC guidance on penalties is here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/penalties-an-overview-for-agents-and-advisers

-

13Meaning that an enquiry was opened on this or some unrelated matter for that year, and it has not been resolved

37 responses to “New report: how Premier League Football clubs have avoided £470m of tax, and how to stop it”

If HMRC fail to pursue premier league clubs for outstanding amounts do you feel such a decision would open the door to companies/individuals who have been penalised by HMRC for adopting similar practices to sue for recovery? Are there fairness clauses inherent in tax law and its application?

Doesn’t HMRC have an open-ear policy? ie they are at the other end of a phone to give direction or sort out a query. Is it credible that there has been no dialogue between HMRC and clubs on this matter? Would it be open to you Dan to make a FOI request to HMRC seeking any advice they may have offered on this subject to any footballing party?

Was wondering if you had already been alerted to the recent FTT decision in Sports Invest UK Limited? Haven’t studied in great depth yet but concerns VAT on football agent services (albeit not in relation to a premier league club and probably quite fact-specific). The conclusion appears to be (perhaps surprisingly) on the facts that all the consideration related to services supplied to the club. Interested to hear whether you think any implications for your analysis (aware only FTT and may be appealed by HMRC).

https://financeandtax.decisions.tribunals.gov.uk/judgmentfiles/j12718/TC%2008797.pdf

Thanks! Will be writing on it soon

For players above a certain level of recognition, with sponsorship/endorsement deals, it seems to me that they have a better case in common sense for claiming to run a business than most of the programmers challenged by IR35.

Arguably the continuing to play for a club is something done largely to maintain their brand value for sponsorships.

So I would have expected them to be self-employed with the agent’s fees as a deductible expense.

Was that the case at one stage, killed by IR35?

Sorry, my first writing was overly condensed – let’s try this:

The loyalty of the agents is to the players.

When they represent the players negotiating with sponsors, that seems to be very much a business expense, and therefore the cost of the agent is deductible.

Whether the player is taxed as self-employed, Ltd, LLP, or a partnership where he signs himself, makes no difference.

(I don’t think anybody would claim a player was an employee of a sponsor)

When the same agent is negotiating for the same player with a Club, the difference is that the resulting contact is one of employment (there is certainly no substitution possible!)

The fees of the agent look to me to be wholly and exclusively to do with the earning of money.

“Necessarily”? Well, in the sense that they result in more income (and so more tax paid) I would say yes.

So while I agree that the 50-50 papering is farcical and does not stand up as tax avoidance, I question “The player therefore shouldn’t be able to deduct the agent’s fees from his income tax bill”.

And as regards the VAT, for players earning more than £85k, they should be VAT-registered, and so while the agents should charge VAT, that would be reclaimed. (or do they push it all offshore?)

Is it possible that HMRC see the potential for 100% deduction of the agent cost as a business expense by the employee, and so consider getting 50% disallowed as a good outcome?

Or are the players still deducting the 50% as a business expense, in which case the numbers from correcting the farcical paperwork are much smaller?

… earning more than £85k from sponsorship …

I don’t think that the fees would be deductible by the player from his employment income as they are not incurred ‘ ‘in the performance of the duties of the employment’ (s336 ITEPA 2003). I would take this to be whilst on the pitch!

Like John Barnett, I don’t think it’s that simple. Assuming it’s not a sham, the correct starting point under modern Ramsay statutory interpretation is not to simply ignore the 50/50 deal as follows from para 53 of the case below:

“The correct response of the courts was not to disregard elements of transactions which had no commercial value. That, he said, was going too far.”

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2022/2770.html

Also, PA Holdings etc. may be germane here as a non-Ramsay case of substance over form re the “realistic facts”, but that all depends on the evidence. Such non-Ramsay cases where HMRC are successful do not involve any purposive widening/narrowing of the literal legislation to defeat realistic facts that would otherwise pay less tax. HMRC wins such cases based only on the realistic facts as found applied to the literal legislation. Also, as you know, some legislation (e.g. probably s62 ITEPA 2003) is not amenable to Ramsay purposive modification e.g. Mayes and para 86 here http://taxandchancery_ut.decisions.tribunals.gov.uk/Documents/decisions/Clive-Bowring-Juliet-Bowring-v-HMRC.pdf .

So it’s all really only about the realistic facts here i.e. the evidence and it’s hard for anyone to prejudge that.

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2022/2770.html

This recent CoA case shows that finding and applying the realistic facts to the legislation (purposively construed), is not always simple: https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2023/362.html

Dan, expanding the argument I started on Twitter. Why doesnt the same logic apply to payments made by professional firms to recruitment agents? Putting it more confrontationally, have you (and indeed I) benefited from the same tax avoidance you are challenging here?

s201 ITEPA Employment-related benefits

(1)This Chapter applies to employment-related benefits.

(2)In this Chapter—

“benefit” means a benefit or facility of any kind;

“employment-related benefit” means a benefit, other than an excluded benefit, which is provided in a tax year—

(a)for an employee, or

(b)for a member of an employee’s family or household,

by reason of the employment. For the definition of “excluded benefit” see section 202.

(3)A benefit provided by an employer is to be regarded as provided by reason of the employment unless—

(a)the employer is an individual, and

(b)the provision is made in the normal course of the employer’s domestic, family or personal relationships.

(4)For the purposes of this Chapter it does not matter whether the employment is held at the time when the benefit is provided so long as it is held at some point in the tax year in which the benefit is provided.

(5)References in this Chapter to an employee accordingly include a prospective or former employee.

There is no doubt that the recruitment agents provide a benefit to the candidate (help drafting CVs, advice on which firms to apply to; longer term career advice), but which is paid for (at between 15% and 30% of year 1 salary) by the professional firm. (NB at a higher rate but on a much smaller sum than the footballers). On the legislation above, the bit that relates to the advice to the candidate should be taxable.

Did Clifford Chance ever tax it? Of course not.

So its really a question of fact. Is the 50:50 split the right answer? Probably not, but the ‘right’ answer will be incredibly fact dependent and will require lots of investigation. 50:50 taxes something, unlike with Clifford Chance and every other professional firm. I’d rather have HMRC use their resources on the black economy and transfer pricing with multinationals, than spending three years on this.

I’m going to write about this soon, but there are two big differences. First, a football agent has a long term relationship with a player, often over their entire career. They are paid a % of lifetime earnings. It’s not a one-off transactional relationship. Second, a football agent is an agent for the player; a recruitment consultant is not normally an agent.

You are right that the recruitment agent is also conflicted in their duty to the employer because their fee is usually a proportion of the starting salary (as employer I therefore try to set the fee as a fixed proportion of the *expected* salary)

I see the difference being in who chooses the intermediary.

If Clifford Chance have appointed Egon Zehnder to find a candidate, a potential employee does not have the option of asking Hays to act in the role.

(yes, I know other agencies sometimes try and the disputes that arise!)

Governments have always tackled the football business with great reluctance. HMRC in this case will be, or have been, pressed by the government via No10 and the Treasury to back off. The reason is of course because governments are wary of the numbers at the disposal of clubs. Millions of carefully considered votes can in practice be spun against a government on the volley if HMRC shapes up to slide in.

If £1b “isn’t a lot of money” (Prescott) then £470m over eight years isn’t worth a penalty shoot out.

I’ve been thinking more about the maths of this report. I think the calculation is flawed. There is absolutely an ‘avoided tax’ number, but I don’t think it is correct to say that it is 80.8% of the fee paid directly from club to agent. The 80.8% is the sum of the income tax (45%), EE NIC (2%), ER NIC (13.8%), and VAT (20%) not received by HMRC. But those percentages are not applied to the same base, because some of them (ER NIC and VAT) need to be netted down and the rest of them (income tax and EE NIC) are only applied to the net base. So instead of 80.8%, I believe the correct percentage is 61.2%. That accords with your example where £306k was the tax ‘saving’. Obviously still big numbers, but quite a material difference.

I would then go further and say that the logic is flawed in another way (see one of my other comments below). Because of the netting down and cumulative way the taxes are calculated, the agent’s fee is higher in example 2, meaning the agent will pay more income tax and EE NIC (to be precise, £104k more). This means the avoided tax number would actually be £201k, and the implicit rate is 40.3%. Again, quite a material difference – although I acknowledge that your model does not take into account agent taxes, so this is not an error as such. But I think perhaps a fairer reflection.

I promise I really am fun at parties.

The Newcastle United v HMRC Tax Tribunal case of 2006 was followed by another VAT Tribunal case involving Birmingham City (2007 UKVAT V20151) https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/uk/cases/UKVAT/2007/V20151.html&query=(%22Birmingham)+AND+(City%22)+AND+(HMRC)

At paragraph 62 the Tribunal state “it is not possible to take the documentary evidence produced by BCFC (Birmingham City FC) at face value.

Dan

Does this also mean that the amounts paid to the agent by the premier league club’s company/corporate entity is not deductible (under wholly and exclusively purpose test) for corporation tax purposes?

Therefore, there is potential for additional amounts of corporation tax liabilities arising depending on the tax profile of the entity concerned i.e. tax losses b/fwd, claiming group relief etc.

well that is a very interesting point…

on the one hand, paying someone to negotiate against you does not seem wholly and exclusively for the benefit of the trade.

On the other hand, in the “normal” scenario where the payment is made by the club as a benefit in kind for the player, it would be deductible for the club (i.e. as it’s part of the player’s remuneration).

It seems an unfair result if the tax-motivated direct engagement gets a worse corporation tax result than the “normal” engagement – but certainly not impossible..

Hi Dan,

Noob question – in the second example, why does the agent not pay tax on the £500k received directly from the club?

I don’t know anything about Tax really, appreciated if explained

The agent pays tax in both scenarios, and then whoever the agent spends its money on pays tax, and then they pay tax etc etc. But we focus only on the club and player’s tax.

It’s a good point though. The amount of income tax and NIC the agent pays increases in Example 2 because the amount of the ex-VAT fee is higher. To show the ‘true’ tax avoided number, wouldn’t we need to adjust for that?

The way I look at it is this: in our example 2, the club is declaring to the FA that it has paid £500k to the FA.

If this is now successfully attacked by HMRC then tax due will be 13.8% employee national insurance, plus 47% income tax/employee NI, plus 20% VAT. So – £404k, i.e. 80.8%.

Now I can see if they’d anticipated that result from the start then (depending on budgets etc) they might have grossed-down the payments so that you end up with 61.2% tax paid. But they didn’t, and we can’t be sure how the payment would have been adjusted in that scenario.

Which figure is the “tax avoided”? That’s something of a philosophical and unknowable question. On the other hand, how much tax do I think HMRC can collect from them now? 80.8%

That’s true. Retrospectively netting down is a bit like having your cake, finding out it was never your cake, and then trying to eat it anyway. Either way, millions at stake. The clubs will hardly win any favour by quibbling how many millions!

Have you considered whether there should be “grossing up”? That would concentrate a few minds.

The pedant in me says that, in the illustrative Example 1, the agent fee is not £lm but is in fact £878,735. The remaining £121,265 being ER NIC which comes out of the club’s pocket. I am fun at parties.

You are entirely correct! I should have said the budget to pay agents was £1m!

The VAT issues with dual representation were covered in (no doubt of historic interest only) in the VAT Tribunal case Newcastle United Plc v Revenue & Customs [2006] UKVAT V19718 (21 August 2006).

Yes – the tribunal was, as I recall, fairly disbelieving. I believe the adoption of the term “intermediary” was in part driven by the case. But in substance nothing has changed.

Arrangements with three or more parties – e.g. the tripartite situation of club, player and agent; possibly with an old club in a transfer situation – are often difficult to analyse from a legal and tax perspective – who is doing what for whom and why – but I’ve seen it suggested that HMRC (or at least teams within HMRC) have previously allowed a 50:50 split on a case-by-case basis in writing, and this became seen as an “industry best practice” which HMRC “commonly accepted”, at least before the new guidance was published in March 2021.

Assuming for a moment that it is possible for an “agent” or “intermediary” to act for both sides in a bilateral transaction of this sort without irreconcilable conflicts of interest (it is hard to see that the club and the player have much of a common interest, when the main role of the agent is to negotiate the terms and conditions of the player’s employment) there are some basic factual questions here:

* what services does an agent provide to the player?

* what (if any) services does an agent purport to provide to the club?

* what are any services provided by the agent to the club really worth?

* why does the value of those services depend on the wages paid by the club to the player?

It is difficult to see what services the club might be paying the agent to provide in the case of a new contract with an existing player. You can’t negotiate with yourself. I can see more of an argument in the case of a transfer, where there may be scope for the agent to negotiate with the old club on behalf of both the new club and the player together. But is this what happens in practice?

Many thanks – I agree with all that. The four-way scenario is indeed potentially legit, so we prudently excluded them from our calculations.

The clubs certainly thought HMRC was okay with 50-50, which HMRC vociferously denies. In particular, I believe HMRC doesn’t accept its recent guidance represented a change of practice.

I have no particular expertise or experience in this area, but some people who do have gone on record saying that HMRC accepted the 50:50 split until relatively recently.

A couple of examples:

* https://www.saffery.com/insights/news/new-hmrc-guidance-football-and-payments-to-agents/

* https://www.blasermills.co.uk/insights/uncategorized1/changes-to-the-hmrc-tax-guidance-for-football-intermediaries-and-agents/

While we are at it, there are some slightly eye-opening comments on the ethical issues here:

* https://erkutsogut.com/can-i-negotiate-with-myself-football-agents-multiple-representation/

(such as agents acting for both clubs and the player at the same time, or “party switching” by terminating their role as player’s agent just before the transfer goes through to engage solely with the transferee club instead)

And some more here:

* http://footballagentblog.chironsportsandmedia.com/2016/07/dual-representation-in-football-pt-2/

And then, from 14 years ago:

* https://www.theguardian.com/football/2009/feb/04/agents-premier-league-dual-representation

“”It is not in players’ culture to pay agents … If the agent helps to secure a deal for a club, then negotiates the player’s salary package, why shouldn’t he be paid by the club? There is no conflict of interest.” Says an agent.

From the outside, there seems to be a “wild west”/”anything goes” approach in play here.

Absolutely – a Wild West, and perhaps the last major sector where tax avoidance is normalised.

I don’t know whether clubs have a good case that HMRC at one point accepted 50-50 without question. However senior sources at HMRC have vociferously denied to me that was ever the case.

Towards the start of the article, you mentioned – but then entirely ignored – an important point here. You say that agents are “sometimes called intermediaries”. But in law an agent and an intermediary are different. An agent is the representative of a person and has authority to act on behalf of that person. An intermediary is a genuine middleman between two parties. Take, in a different area, a matchmaking service (say Tinder). Tinder is an intermediary between two people wanting to form a relationship. It doesn’t (I understand) favour one side or the other. (I understand that specialist providers can be found who will act for one party or the other in such a situation, but that is less typical).

Is the third-party in the relationship between club and player more akin to agency or intermediary? I guess traditionally, yes, it is more akin to an agency relationship where the third-party is agent for the player. But, to take another area again, while an estate agent may (contractually) be the agent of the seller and nominally trying to get the best price for the seller, anyone who has ever sold a house knows that the estate agent’s loyalty does tend to shift (in practice if not contractually) to the buyer – because only if the sale goes through does the estate agent get paid. So, while initially the agent may be trying to get the best price for the seller (because they will get a higher commission), their overriding interest is in the sale going through at all (and getting paid some commission rather than no commission).

Arguably, therefore, an intermediary relationship, properly defined in a contract, is a more honest relationship than an agency relationship – the problem with the latter being that (s)he who pays the piper ultimately calls the tune.

Does this apply in every case? Clearly not. In some cases (presumably particularly for high-profile players with long-standing agents and where the player is already wealthy enough to afford the agent’s services from existing resources) the agent will do the traditional job and will fight solely for the player. But in other cases (presumably newer, or less popular players) arguably an intermediary relationship is a more contractually honest representation of the true position.

So I don’t disagree with you that in some cases the position may well have been exploited. But I do disagree with you that the true contractual relationship is “obvious” or that”realistically the agent is acting only for the player”. I think that the reality of the position is more nuanced.

In a complex situation like this, I would think it within HMRC’s care-and-management powers to agree some sort of guidelines or indicia of which sort of contract is genuinely which – rather than having to negotiate each case from first principles.

And, I suppose, one wider point – has anyone given thought, at a macro level, as to whether 62% is a “fair” tax rate for payments to agents?

I

They used to be called “agents” and the terminology only changed to support the creaky tax analysis. So I prefer to use the term that I believe is legally and historically correct, as well as more easily understood.

Your description of the motivation of estate agents is absolutely what I have always thought but never seen anybody else write down – the problem is that 1.25% of total sale price gives too small a marginal motivator to act in the interest of the seller.

The rational response from seller (and not just for houses) is “Selling this for £X involves no expertise – I will pay you 10% of (sale price – £X)”

I tried to get some estate agents to work like that but they refused.

If I ever sell a business I will try the logic again.

Nice one Dan. For a moment I thought it was going to be about image rights! Does the same thing happen in other sports (such as rugby)?

Image rights have largely been closed down/abandoned, I believe.

Whether other sports do the same thing is a great question. Obviously the money will be much less, but there’s still a powerful incentive…