The UK charged 20% VAT on ebooks until May 2020, when it was abolished following a lobbying campaign by the publishing industry. They claimed that consumers would benefit from lower prices. Our analysis shows that this didn’t happen – publishers retained the VAT saving for themselves, costing the country £200m.

Background

Books have always benefited from 0% VAT. Ebooks were subject to 20% VAT.1Historically, EU law permitted reduced or 0% VAT on books, but required ebooks to be subject to the full rate – so 20% in the UK. That was changed in October 2018, permitting Member States flexibility in what rate they applied. An EU law change in 20182In July 2019 many EU states reduced the rate of VAT on ebooks. The UK didn’t follow until March 2020, when the then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced that the UK would cut the rate to 0% from end 2020. Then in April 2020 he announced the cut would be accelerated to May 2020. permitted the UK to reduce the rate of VAT on ebooks, which the UK initially resisted. Following a lobbying campaign from the publishing industry, the UK scrapped3Technically this was a reduction in VAT from 20% to 0%, which is different from an exemption (and more favourable, because it means retailers/publishers can claim a refund of VAT on their inputs/expenses). In the interests of clarity we will use terms like “scrapped” and “cut” because we think that is easier to understand, and the further technical consequences of a 0% rate are not relevant to this report VAT on ebooks4VAT was also cut for electronic newspapers/magazines, but that’s outside the scope of this report in March 2020. The cost to the Exchequer was £200m.5See page 66 of the March 2020 Budget Red Book, item 15

The Axe The Reading Tax Campaign (run by the Publishers Association) said that removing VAT from ebooks would result in lower prices for consumers:

Did it?

Our conclusions

We analysed the detailed ONS sampling data of ebook pricing, compiled as part of the consumer price index. We found no significant change in ebook pricing around the time of the VAT cut. Full details of the ONS analysis are below.

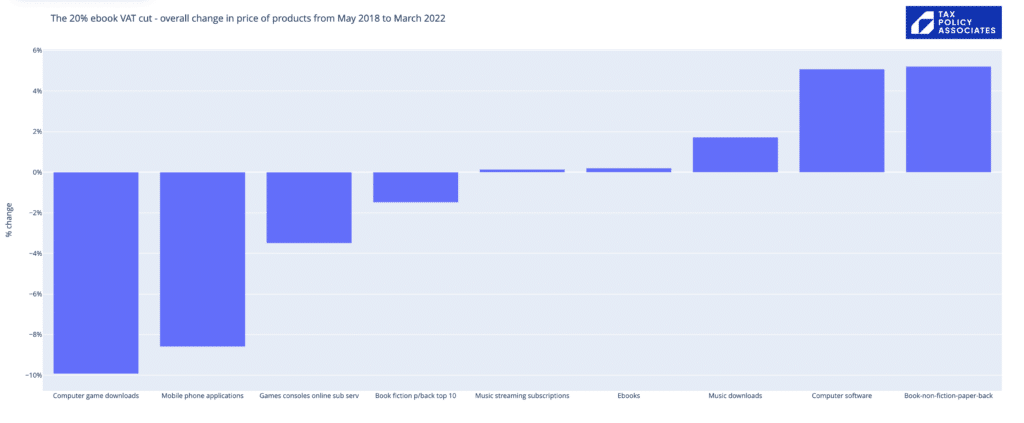

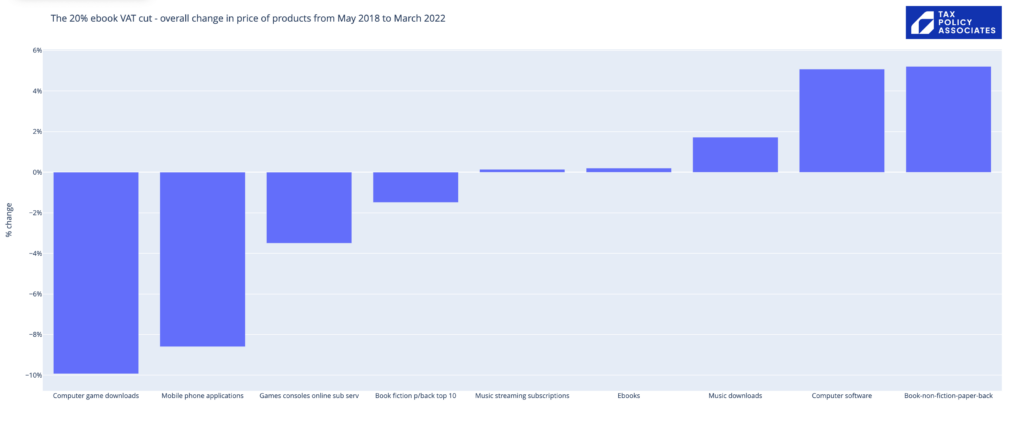

This is the key chart, showing the change in average pricing for the 23 months6We set the cut-off at 23 months because inflation tends to dominate after Q1 2023 before and after the VAT cut, for both ebooks and other comparable products:

The VAT cut means that ebook publishers could have cut their prices by 17%7Why 17% and not 20%? Because a £10 ebook before May 2020 represented a £8.33 price plus £1.67 VAT. After May 2020, the publisher could charge £8.33 and receive the same net proceeds – that’s a 17% price cut to the consumer. and made the same profit. They didn’t. Over this period there were 8%+ price reductions for comparable products – computer game and app downloads – where there was no VAT cut. There were no overall price reductions for ebooks.

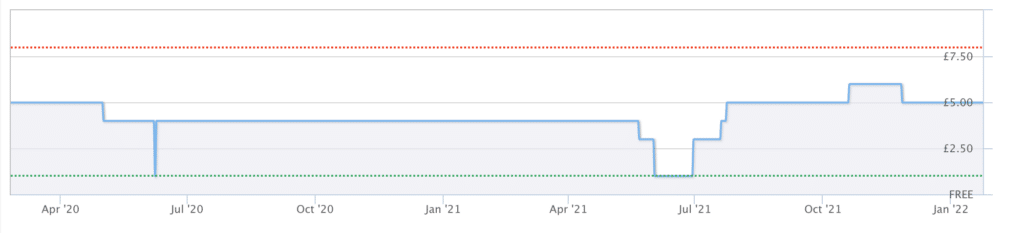

We also analysed individual pricing data for the 30 best-selling ebooks on Amazon UK in 2020 (as Amazon is by far the most significant ebook retailer). Only (at most) four out of thirty showed a sustained price reduction which could plausibly have been attributed to the May 2020 VAT cut. That likely overstates the effect.8Overstates because these changes could be coincidental; only one was the “correct” percentage price cut at the “correct” date; also the prices of individual books tend to fall after they are published. The ONS data samples the ebook market as a whole, and so is not prone to these problems. Full details of price movements on these ebooks are below.

VAT was also cut for electronically delivered newspapers and magazines – that’s not something we’ve looked into in this report.

Perhaps there was a benefit to consumers, but that was hidden by increased costs/inflation?

This is often the excuse for a failure to pass on VAT cuts, but it doesn’t wash here – this is an unusually clear effect:

- These are ebooks. The usual fluctuations in price of inputs such as e.g. paper are irrelevant.

- This was a big cut in VAT at one moment in time. It would be easy to spot the effect, if there was one.

- Inflation over the period was low, much lower than the VAT cut, and was concentrated in other areas, e.g. energy prices.

- There is an easy comparison with other downloaded products, which have a similar cost base and supply/demand factors.

Perhaps the cost of paper was rising, so book prices increased, and publishers felt ebook pricing had to follow book pricing?

There’s no evidence of that. Paperback fiction pricing dropped slightly across the period we looked at (1%); non-fiction pricing rose slightly (5%).

Who benefited?

Amazon dominates the UK ebook market. Precise up-to-date figures are hard to come by, but its UK market share in 2015 was estimated as 95%; that has now come down, perhaps to the level of its global ebook market share of around 67%.

However, ebook prices are set by publishers, not Amazon. The publishers lobbied for the VAT cut. In May 2020 they could have reduced their prices by 17% and received the same post-VAT income. They didn’t.

Amazon generally retains a royalty of around 30%, so we can say that of the £200m annual cost of the VAT abolition, Amazon received about £60m and publishers/authors about £140m.

To put these figures in context, the publishing industry’s UK profit in 2021 was probably around £200m. Even after increased author royalty payments, this looks like a very significant enhancement to publisher profitability9Publishing industry UK revenue was £3bn in 2021, with a profit margin of about 6% (that figure is a rough estimate from industry sources).

What does this mean?

Our conclusions above are unlikely to surprise either consumers or tax policy specialists. They reflect what we found when we analysed the impact of the January 2021 abolition of VAT on tampons. We believe they also accord with common sense.

Professor Rita de la Feria is Chair in Tax Law at the University of Leeds, and probably the world’s leading academic expert on VAT. Professor de la Feria has previously written about how special interest groups (publishers, in this case) lobby for favourable VAT changes, and has kindly reviewed a draft of this report. She says:

“These results are consistent with previous empirical studies on VAT cuts carried out in many countries and as regards a wide range of products: VAT cuts tend not to be passed through fully to consumers. So, decreasing VAT tends to help businesses, not consumers. It is also important to note that, even if the cut had been passed [to consumers], a tax cut on e-book sales would increase the regressivity of the tax system, as we know that those products are overwhelmingly consumed by those on higher incomes. So, it represents in effect a tax cut on the richest, at the time when we should be protecting the poorest.”

Despite this evidence, we risk repeating the ebook experience, this time with sunscreen. An MP tabled an Early Day Motion. The House of Commons is debated cutting VAT on sunscreen . The Government has sensibly noted that any VAT cuts may not be passed onto consumers. The House of Commons Library has published a research paper citing our tampon pricing research.

We hope MPs will review the evidence of the impact of well-intentioned VAT cuts, and stop lobbying for VAT cuts that will benefit industry rather than consumers.

Methodology – analysis of ONS data

We followed the same methodology we used for our “tampon tax” report last year – a python script analysed ONS inflation data to track price movements in ebooks and other comparable products. That approach is explained in detail in our tampon tax report, and all the code and data for our ebook analysis is on our Github. We welcome comments and criticisms.

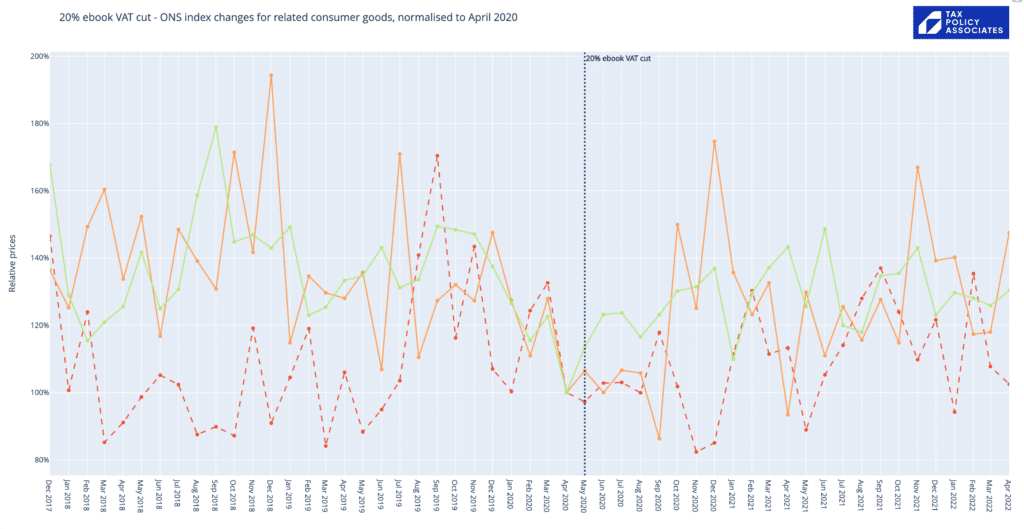

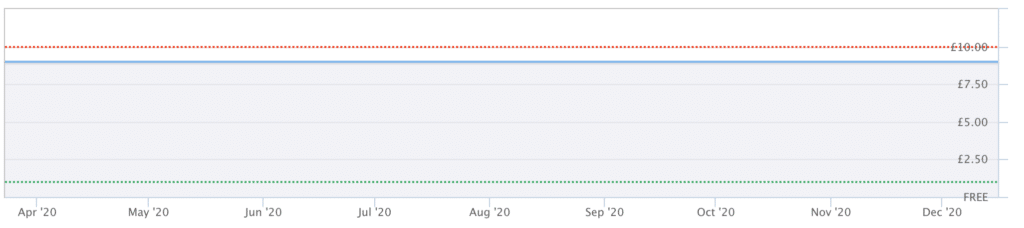

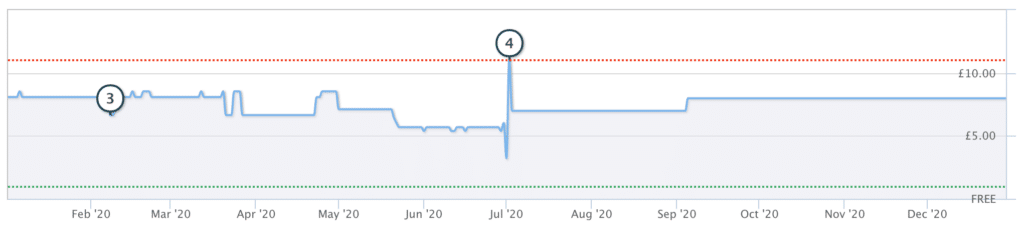

This interactive chart (full screen version here) shows how ebook pricing changed across the point when the 20% VAT was abolished. It’s clear there was no change at all:

The chart is normalised to April 2020 – i.e. we call the April 2020 prices 100%, and everything else is relative to that. Inflation (CPI) was low at the time (you can add that into the chart as well). We stop at two years because, after March 2022, inflation starts to dominate, and render this kind of analysis much more difficult.

There was an immediate 3% drop in ebook pricing from April 2020 to May 2020, when the VAT cut took effect. However the volatility in pricing means that does not give a true picture of the effect of the cut. The volatility is considerable, with a 70% increase in Autumn 2019 and then more-or-less a reversion to the previous trend.10It is interesting that, just as with the tampon data, there is an apparent price increase immediately prior to the VAT cut. The July spike in UK ebook pricing coincides with the moment when many other EU member states cut VAT on ebooks. However for now we are putting this down to a coincidence rather than any intentional pricing manipulation.

There is an even higher level of volatility for the two best comparators – mobile phone apps (green) and computer game downloads (orange):11We consider apps and computer game downloads the best comparators because, like ebooks, pricing is set by publishers. By contrast, music download pricing is subject to a more complex negotiation between platforms and publishers; subscriptions are (for obvious reasons) less volatile

So it is sensible to look at averages across the 23 month12We have a 23 month cut-off because inflation effects start to dominate once we get into Q2 2023 period before and after the May 2020 VAT cut:

This shows almost no change in ebook pricing. Over the same period, the price of physical books rose by 5%, as did computer software; the price of music downloads increased by 2%; computer game downloads and mobile phone apps had åverage price reductions of over 8%. Of course none of these other products experienced any VAT change.

CPI rose by 8% across that period, mostly post-pandemic and then immediately after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but that was largely driven by price increases in housing, energy, fuel and transport.

We would conclude from this that there is no evidence of any price reduction in ebooks.

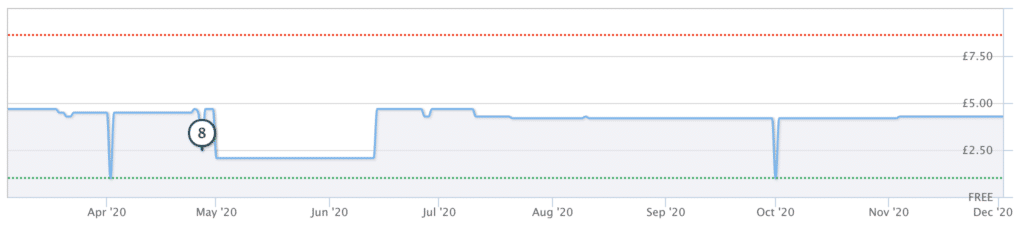

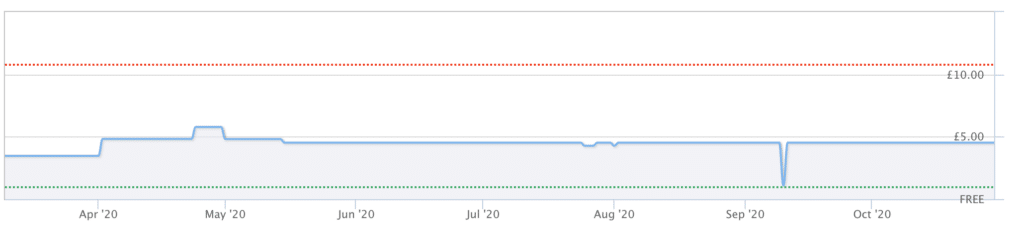

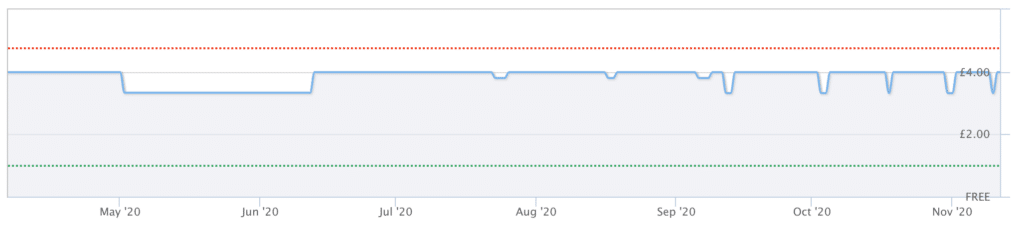

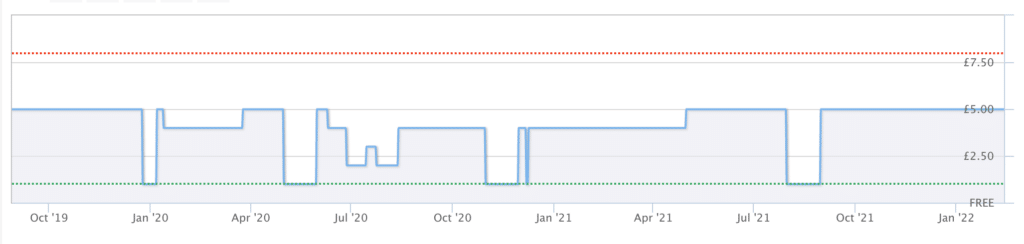

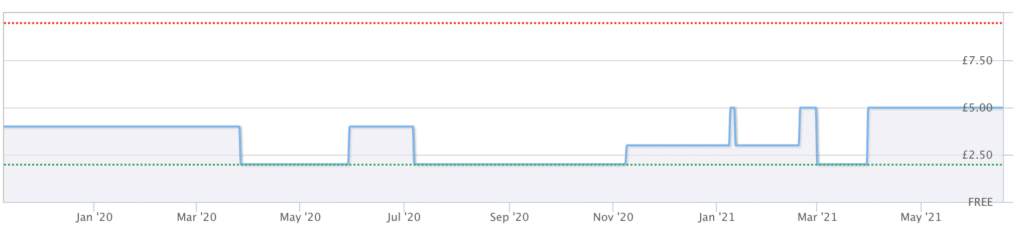

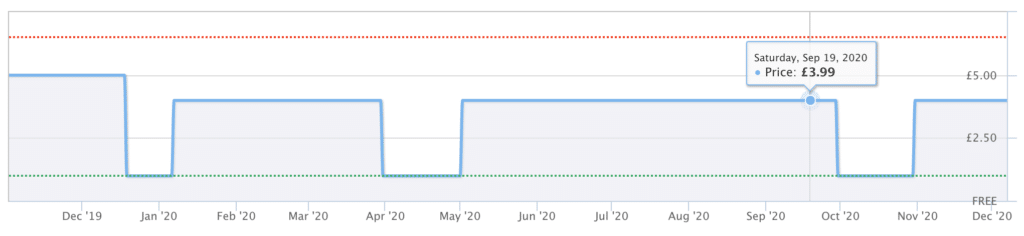

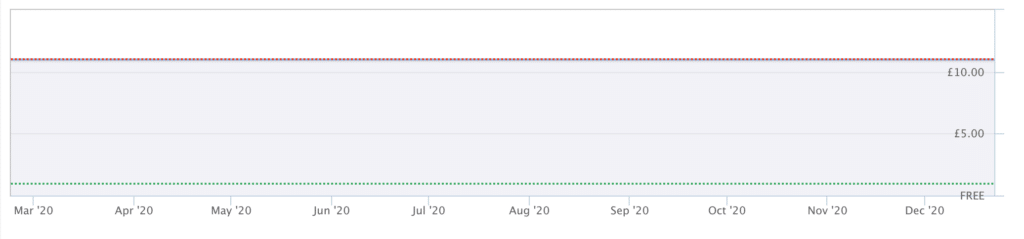

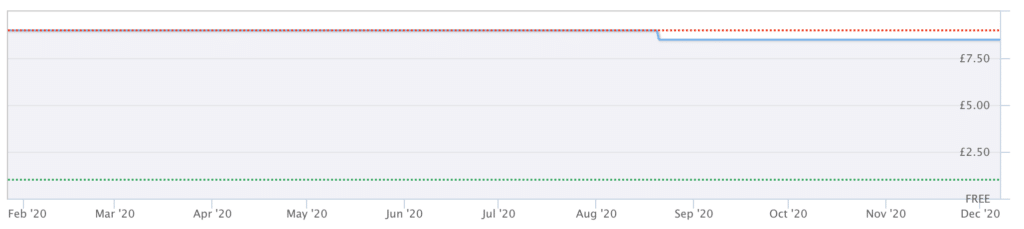

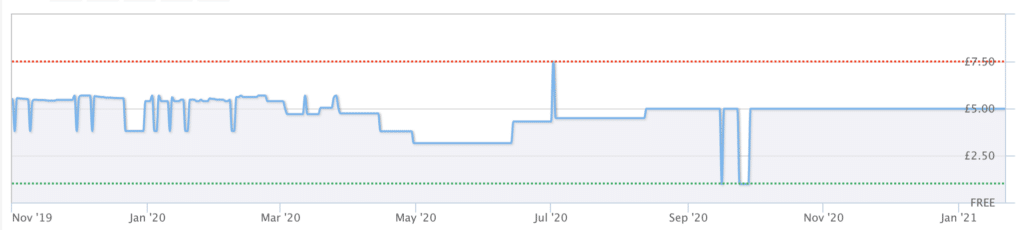

Methodology – pricing data for the top 30 ebooks sold on Amazon UK in 2020

To sense-check the ONS results, we looked at historic ebook pricing tracked by the wonderful website eReaderIQ for the top 30 ebooks from Amazon’s 100 bestselling books in 2020 (skipping over those where eReaderIQ doesn’t have data, e.g. because no ebook was available on April 2020). All charts are taken from eReaderIQ, with their kind permission.13We would discourage anyone from scraping the website to try to research pricing further; for the reasons we mention we don’t think this could achieve statistical validity; it would also abuse a fantastic service

It is important to note that this approach has no statistical validity as, whilst we have pricing data for each book, we don’t have data on the number of sales of each book, total Amazon UK ebook sales, or total UK ebook sales. Furthermore, looking at individual books may give a false impression of price cuts which do not reflect the market as a whole.14i.e. because many books will decline in both sales and price the longer they remain on the market, and so tracking individual books (as opposed to the market as a whole) may given a false impression of price cuts (a type of cohort effect).

So why look at individual book pricing at all? Because if, for example, we saw most of the top 30 books consistently having a 20% price cut around May 2020, that would call into question our findings from the ONS data. We do not see this. Only four books out of the top 30 show a sustained price reduction consistent with the May 2020 VAT cut. That likely overstates the effect, because these changes could be coincidental; only one book demonstrated the “correct” 17% price cut on the “correct” date.

It’s important to note that Amazon does not set prices. Amazon may have profited from the VAT cut, but it was publishers who chose not to pass the benefit onto consumers.

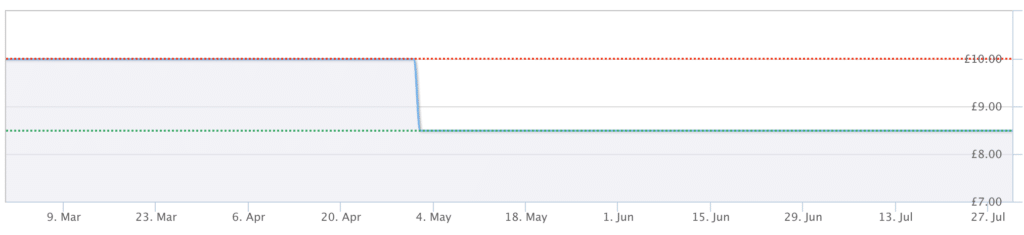

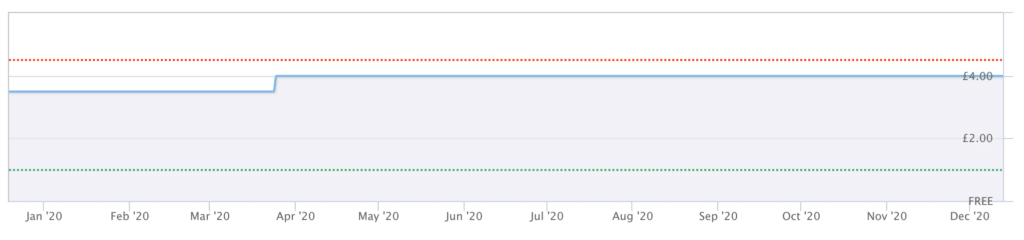

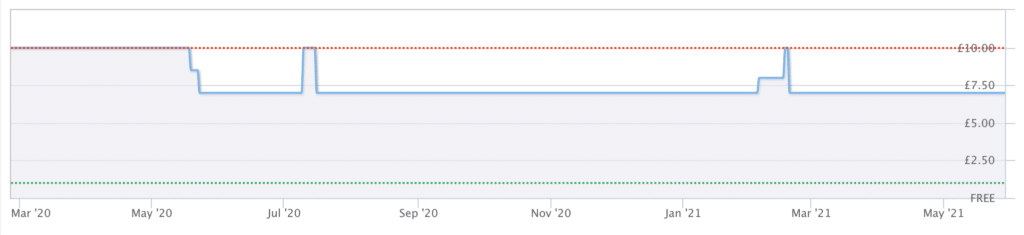

1. The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse:

15% price cut in May 2020 – kept at that level. This is consistent with the VAT cut being passed to consumers.

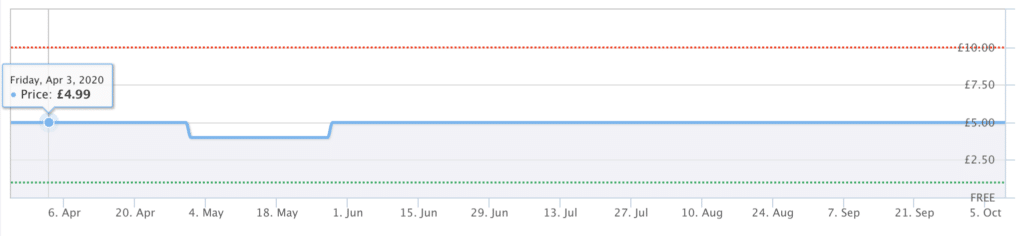

2. The Thursday Murder Club:

15% price cut, but only for four months – then back up.

3. Where the Crawdads Sing:

No change.

4. Pinch of Nom Everyday Light:

No change.

6. Pinch of Nom: 100 Slimming, Home-style Recipes:

No change.

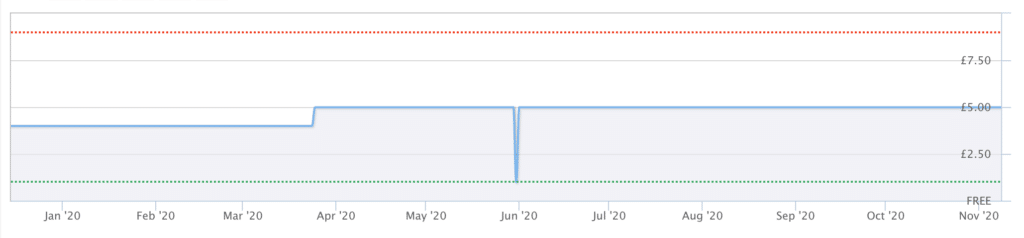

11. Girl, Woman, Other

20% price cut on 1 May 2020, but returning to the previous price on 1 June.

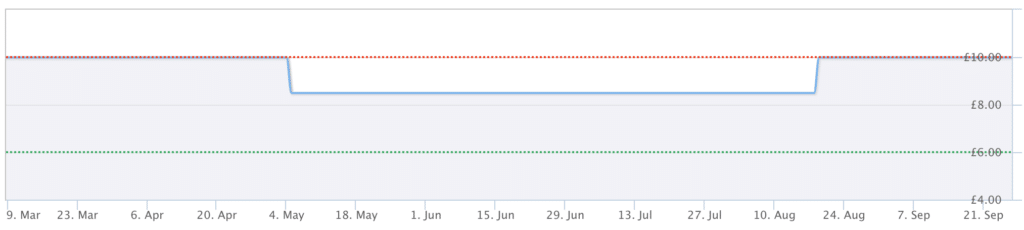

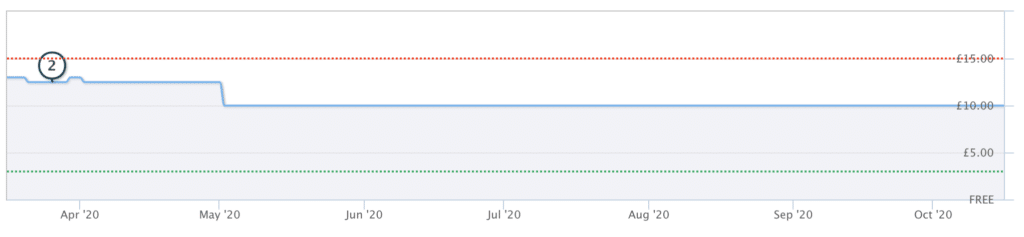

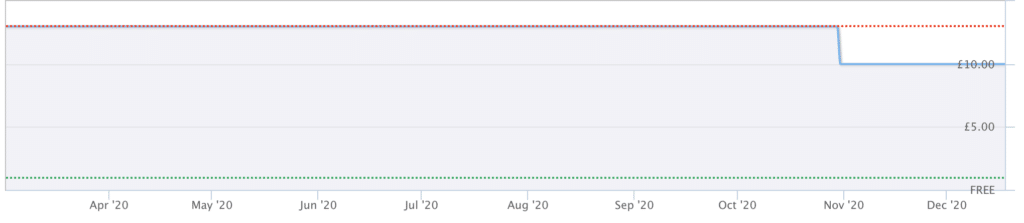

15. The Mirror and the Light

20% price cut in May 2020, sustained. Potentially consistent with the VAT cut being passed to consumers.

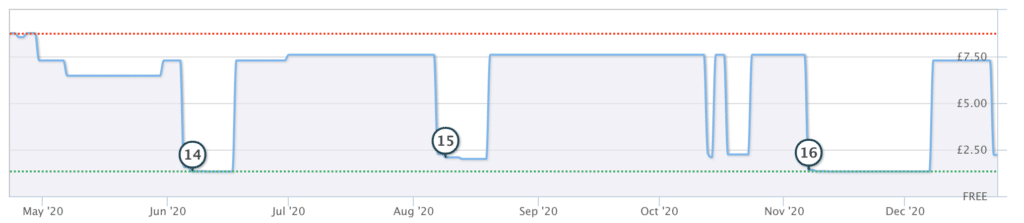

16. Good Vibes, Good Life

17% price cut on 30 April 2020, sustained. That could be an example of the 17% price benefit being passed to consumers; although given it was a newly launched book, it could also be a post-launch price reduction.

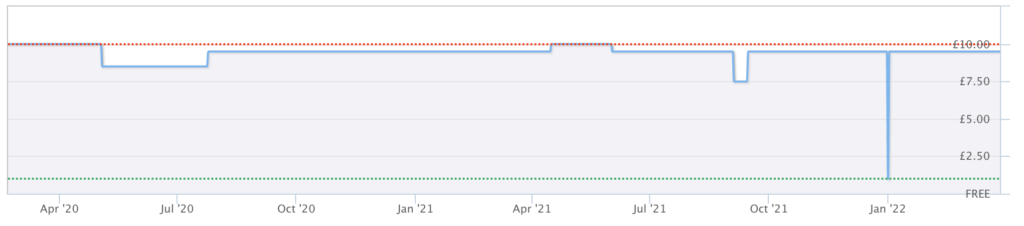

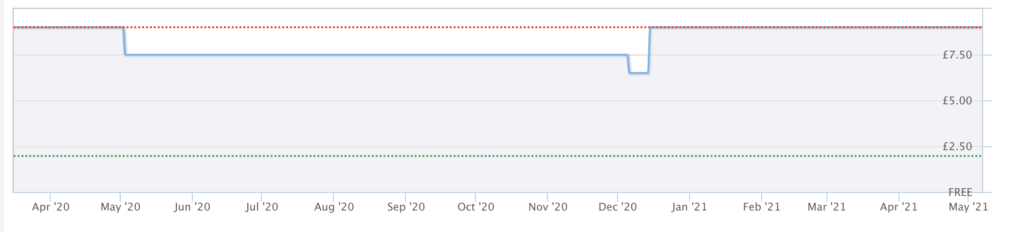

17. Normal people

55% price cut in May 2020, but only for a month.

19. Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race

No change.

20. The Beekeeper of Aleppo

17% price cut in May 2020, but only for six weeks.

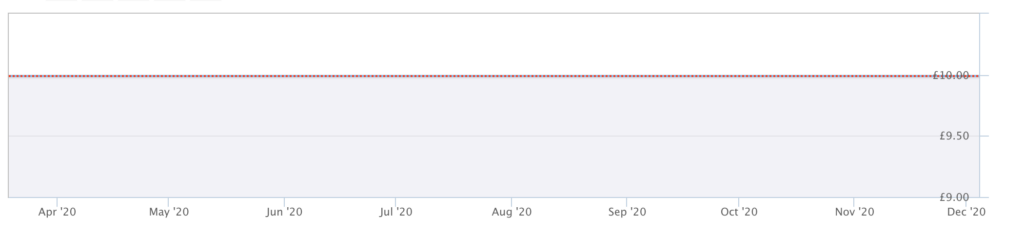

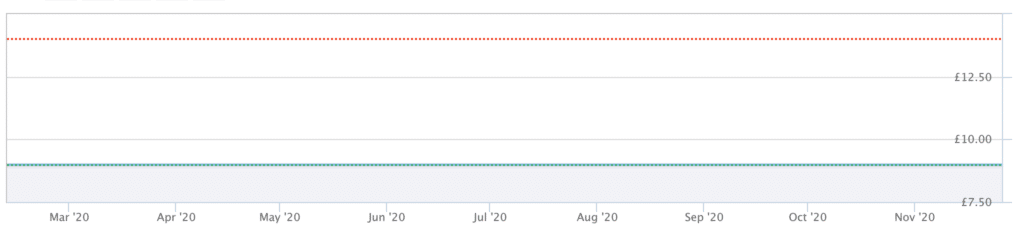

21. The Silent Patient

Lots of variation, but no sustained price cut (and that trend continued right to February 2023).

24. The Family Upstairs

20% price cut, maintained for a year, then back to where it was.

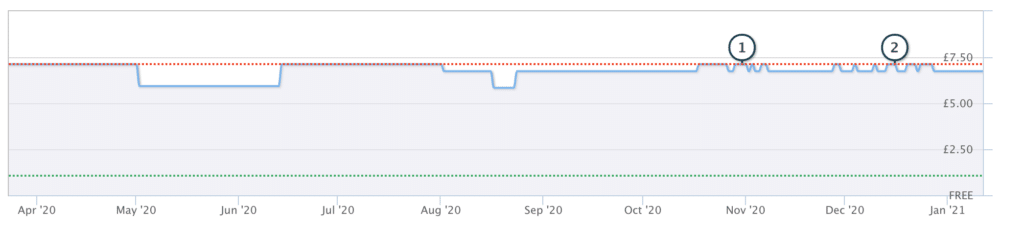

25. Cook, Eat, Repeat:

No price cut.

26. Wean in 15

No price cut.

27. The Fast 800 Recipe Book

No clear trend.

32. This is Going to Hurt

No clear trend.

35. Nadiya Bakes

No price reduction.

36. Blood Orange

No price reduction.

38. Troubled Blood

No price reduction.

40. Shuggie Bain

No price reduction.

43. The Boy At the Back of the Class

No price reduction.

45. Happy: Finding joy in every day

No price reduction.

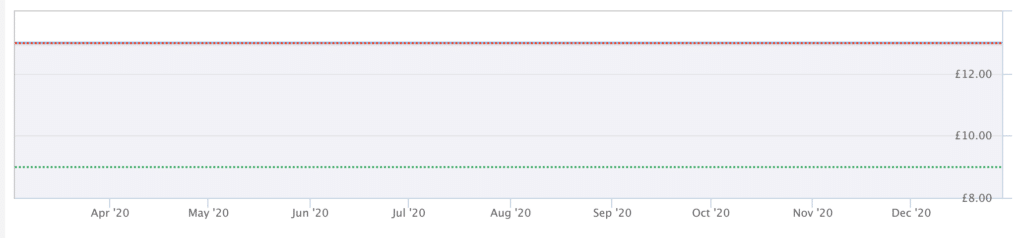

46. Hinch Yourself Happy

15% price reduction for ten weeks, then mostly reversed, trending to a 5% price reduction.

47 Ottolenghi FLAVOUR

No price reduction.

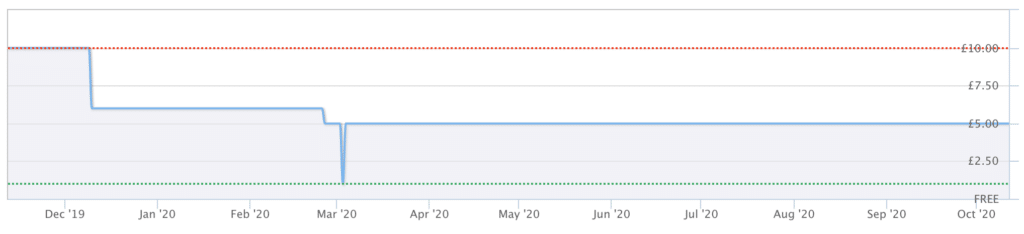

48. The Green Roasting Tin

30% price reduction in mid-May 2020. Potentially consistent with the VAT saving being passed to consumers (although the higher amount suggests there could have been another factor here).

51. Kay’s Anatomy

17% price cut in May 2020, reversed after six months.

52. The Midnight Library

17% price cut in May 2020, reversed after six weeks, stabilising at a 5% price cut.

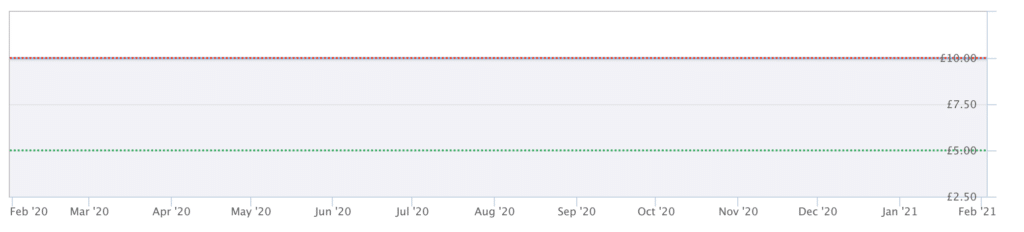

53. The Sentinel

No price cut.

54. The Fast 800

No clear trend.

Many thanks to the ONS for publishing all their CPI data, and being so responsive to our queries. Thanks to eReaderIQ for permitting us to use their ebook pricing tracking data and publish their tracking charts.

Thanks to G and R for their review of an early draft of this report, to J and C for industry insights, and to Professor Rita de la Feria for her comments and her previous work in this area.

Image by Stable Diffusion: “cinematic photo of an electronic book, masterpiece, highly detailed, trending on artstation, 4k”

-

1Historically, EU law permitted reduced or 0% VAT on books, but required ebooks to be subject to the full rate – so 20% in the UK. That was changed in October 2018, permitting Member States flexibility in what rate they applied.

-

2In July 2019 many EU states reduced the rate of VAT on ebooks. The UK didn’t follow until March 2020, when the then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced that the UK would cut the rate to 0% from end 2020. Then in April 2020 he announced the cut would be accelerated to May 2020.

-

3Technically this was a reduction in VAT from 20% to 0%, which is different from an exemption (and more favourable, because it means retailers/publishers can claim a refund of VAT on their inputs/expenses). In the interests of clarity we will use terms like “scrapped” and “cut” because we think that is easier to understand, and the further technical consequences of a 0% rate are not relevant to this report

-

4VAT was also cut for electronic newspapers/magazines, but that’s outside the scope of this report

-

5See page 66 of the March 2020 Budget Red Book, item 15

-

6We set the cut-off at 23 months because inflation tends to dominate after Q1 2023

-

7Why 17% and not 20%? Because a £10 ebook before May 2020 represented a £8.33 price plus £1.67 VAT. After May 2020, the publisher could charge £8.33 and receive the same net proceeds – that’s a 17% price cut to the consumer.

-

8Overstates because these changes could be coincidental; only one was the “correct” percentage price cut at the “correct” date; also the prices of individual books tend to fall after they are published. The ONS data samples the ebook market as a whole, and so is not prone to these problems.

-

9Publishing industry UK revenue was £3bn in 2021, with a profit margin of about 6% (that figure is a rough estimate from industry sources)

-

10It is interesting that, just as with the tampon data, there is an apparent price increase immediately prior to the VAT cut. The July spike in UK ebook pricing coincides with the moment when many other EU member states cut VAT on ebooks. However for now we are putting this down to a coincidence rather than any intentional pricing manipulation.

-

11We consider apps and computer game downloads the best comparators because, like ebooks, pricing is set by publishers. By contrast, music download pricing is subject to a more complex negotiation between platforms and publishers; subscriptions are (for obvious reasons) less volatile

-

12We have a 23 month cut-off because inflation effects start to dominate once we get into Q2 2023

-

13We would discourage anyone from scraping the website to try to research pricing further; for the reasons we mention we don’t think this could achieve statistical validity; it would also abuse a fantastic service

-

14i.e. because many books will decline in both sales and price the longer they remain on the market, and so tracking individual books (as opposed to the market as a whole) may given a false impression of price cuts (a type of cohort effect).

14 responses to “The abolition of VAT on ebooks was a £200m handout to publishers”

I’m surprised that you’re showing consternation over a VAT cut, VAT is such a regressive tax, it’s paid post income tax, is a tax on consumption (it tacitly encourages hoarding one’s money rather spending it), it takes no account of one’s ability to pay it, it is levied the same regardless of whether a poor person pays it or a rich person does at the point of purchase.

Not only that it raises the barrier to entry, consumption tax advocates such as the conservatives and the right in general would like to profess that poor people don’t pay much of it at all as a proportion of their income, but that’s merely a post hoc observation, one can’t pay VAT that they can’t afford!

Not only that, VAT is an inflation multiplier and a demand dampener simultaneously.

Then there’s the whole inefficiency in allocating the bureaucracy in enforcing VAT compliance at the public’s expense as well as resources wasted in the private sector mitigating one’s own VAT liabilities.

I see the main umbrage that you take from this particular episode is that the publishers did not pass on the costs to the consumers.

This is merely a short term contrivance, their margins will eventually contract in line with what they were able to bear before the cut in real terms eventually, this is like a windfall.

On the principle of the matter, I don’t see why physical books that have a real tangible environmental cost as well as a physical labour inefficiency and allocation of physical commodities ie paper and fuel etc, ought be VAT free and the same data, knowledge etc be levied an additional fee.

Also to be somewhat pedantic, that £200 million shortfall to the treasury that you’ve highlighted, is not necessarily that large, as this would be somewhat mitigated by higher receipts of Corporation Tax, Dividend Taxes etc from the profiting parties.

The treasury should be seeking to mitigate the loss of such income through raising other more progressive tax measures, such as income, capital gains and wealth to name but a few.

For anybody else reading, the conservatives and their bankrollers have always held a long tradition of cutting (direct) income and wealth taxes whilst raising (indirect) consumption taxes like VAT and excise duty. In fact when income tax was first introduced by the Liberals, the Tories quickly repealed it once they were in power, much more recently Thatcher raised it to historical highs and slashed income taxes, this shifted the tax burden from the rich to the poor. The current Conservatives have raised VAT to highest rate ever after the outgoing Labour government cut it to 15%, which they didn’t get enough credit for doing.

I’m afraid I disagree with almost all of that.

VAT is slightly regressive as to income, but mildly progressive as to consumption (which is more important). See https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/09chap10.pdf . Certainly the benefit of most VAT cuts, if passed to consumers, will disproportionately go to those who consume more. Even if it worked as intended, a VAT cut on ebooks is a regressive measure, not a progressive measure. Rita de la Feria has written extensively about this.

Will margins eventually contract? I suppose that’s possible, but it has been two years and there is nothing in the data suggesting that it’s happened yet.

The balance between direct and indirect taxes has been much more stable over the last 60 years than most people think – see the second chart here: https://heacham.neidles.com/2022/10/11/four-infographics/

Labour did not cut VAT to 15%. It was 17.5% in 1997 and 17.5% in 2010. Perhaps you are thinking of the temporary cut to 15% in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis? Reversed well before the 2010 election.

Thank you for replying to my verbose post, however I do want to clarify that I am not in favour of VAT being cut without any other direct taxes being raised to compensate such a cut.

I would not advocate such a position as it would ultimately result in some kind of regressive outcome ie cutting of public expenditure, borrowing more etc.

I’m advocating that income taxes would have to rise accordingly on those who as you say stand to disproportionately benefit more from their relative greater consumption, anything less would indeed be regressive. In a similar vein I am well aware that a VAT free Ferrari doesn’t do a whole lot of good for someone on minimum wage.

I appreciate that you’ve appended those charts in your response as well, but they don’t contextualise how the burden of taxation shifted among different income groups which the main point of contention from its detractors, only total receipts from each category are shown, and provided without the actual changes in RATES of income tax and VAT levied.

It almost conveys a zero sum game, as though it’s one homogeneous block of taxpayers who are paying the income tax and VAT, giving the impression that had I been working around 1979 years ago, I would have paid less VAT but more income tax anyway as though tax adjustments since have had the same impact across all income strata. It treats the origins of the revenues as having no consequential importance as though they’re externalities, so as long as the accounts are balanced. So indeed as far as the Treasury is concerned, VAT has not replaced income taxes, but that’s merely a superficial observation.

This is my fault for not clarifying but the often touted claim that tax has shifted from income tax to VAT is an abridged concise claim, it’s more nuanced in that the proponents of that shorthand claim is that the tax burden has shifted to the lower income strata abetted by indirect taxation, for example under Thatcher the top rate of tax being cut from 83% to 40% with basic income tax being cut from 33% to 25%, with the standard rate of VAT rising from 8% to 15% by the end of her tenure. Notwithstanding payroll taxes and others including CGT, this context is absent from your charts and makes the subtle changes in UK tax trajectory appear more innocuous for it.

Also you are correct about the 15% VAT measure by Brown, it was already reverted back to 17.5% before he even held the 2010 election, nonetheless it was raised to an historical high since then.

Back to the original topic at hand, I didn’t want to condone the behaviour of the Publishers here, they acted out of self interest in lobbying the government, extolling promises to the public of immediate substantial material consumer benefits but yet ultimately yielding none. That prices have remained uncompetitive appear to be in breach of anti-cartel legislation, which unfortunately isn’t going to be enforced by the government providing the aforementioned favour.

To be fair (although I’m not sure to whom) prices didn’t seem to especially increase when the VAT rules changed (circa 13-15) and the rate charged moved from that of the Member State of sale to the Member State of the purchaser. IIRC Amazon were selling Kindle books from Lux at a low rate and then had to charge 20% for sales to UK readers.

I contacted a company selling ebook compilations of classic 80s comics back in May 20 asking if they would be cutting their prices – I received no reply!

Thanks – one plausible answer for this and the 2020 effect could simply be that ebook prices track physical book prices, more or less. Which is fine – but the publishers were naughty (or even cynical) in suggesting there would be a different result in 2020.

An interesting analysis, Dan, and one that is probably mirrored across many markets and product sectors, as suggested in Chokepoint Capitalism by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow (https://chokepointcapitalism.com/). They note that industry concentration in the creative sectors, such as book and music publishing, distribution and performance, has been terrible for creatives and customers. A large part of the problem is the ability of corporates to lobby and get legislation and regulations that favour them, as indicated by Corporate Europe Observatory (https://corporateeurope.org/en/lobbying-the-eu).

Fortunately, the mood is changing, helped by your efforts. But even President Biden is having his administration look at Ticketmaster, and the UK’s Competitive Markets Agency this week found the Microsoft/Activision merger problematic, to say the least, for the very reasons explored in Chokepoint Capitalism.

I had some dealings with publishers when they were campaigning on this issue. To a degree I can understand why they didn’t reduce the prices. Firstly For years they suffered a collapse in the price of physical books caused by the dominance of Amazon who used their position to force the price of books down in an attempt to become the only place consumers visited to buy anything (and that is a statement direct from an Amazon employee). This behaviour was paricularly harmful to publishers of academic books who relied on high prices in order to remain viable. Secondly Amazon dominated the ebook market as well taking a large margin. In the light of these factors you can understand why when there was an opportunity to keep the extra margin resulting from the removal of VAT, altjough I am not sure to ehat degree that was also the result of Amazon. Richard Allen RAVAS

I wouldn’t have a problem with them keeping the extra margin if the publishing industry hadn’t lobbied so heavily on the basis that consumer prices would be cut. It still would have been a bad policy idea, but I wouldn’t blame the publishers for taking whatever additional margin they could.

With or without VAT, the average ebook is still ludicrously cheap. According to goodereader.com, the average price of the 100 bestselling Amazon Kindle books was £3.06.

Three quid.

Compare that to a trip to a football match, a night at the cinema or even a pint of beer in London. For a book. That you get to read and keep. Forever.

Thing is, if the publishers had said “we are dying, and VAT is just the final nail in our collective coffin” then I’d respect that. Lobbying on the basis of price cuts, and not delivering them? It’s pure cynicism.

Three quid for a paper book sounds cheap, given the cost of paper and distribution and warehouses and shops and so on.

But what is the marginal cost of production of an ebook, given the publisher must have the text available in digital form already to publish a physical book, and the customer is using and paying for their own device, their own internet connection, and their own electricity, forever, to be able to read it forever?

Ebooks aren’t _always_ forever https://www.theregister.com/2009/07/18/amazon_removes_1984_from_kindle/

Exactly why I prefer proper books!

That was down to incorrect rights. Nothing more sinister than that. Unfortunately it’s become a poster child for those determined to dismiss ebooks.