UPDATED with BP profit announcement and further thoughts

Only a small proportion of Shell and BP’s profit is made in the UK, so we should be unsurprised that only a small amount of their huge profits are taxed in the UK. But when energy companies make “windfall profits”, at the expense of the rest of us, there is a case that normal principles shouldn’t apply, and the windfall should be taxed.

Shell

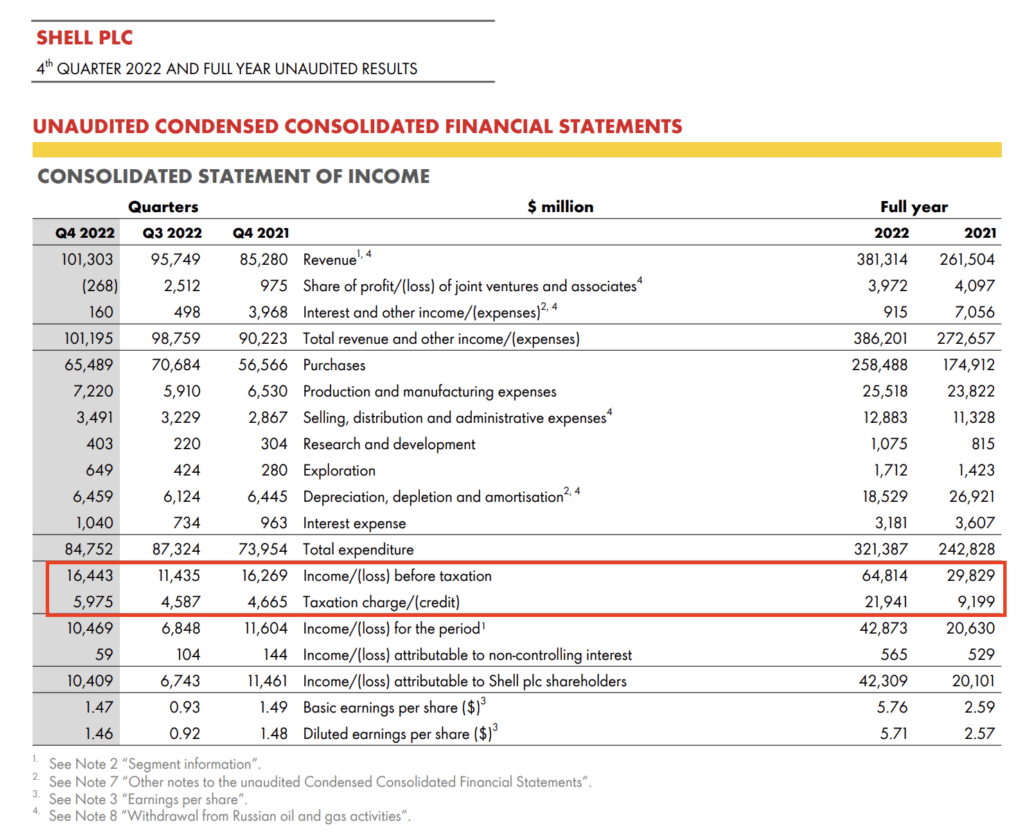

Here are Shell’s unaudited financial statements for 2022:

$65bn of pre-tax profit – more than twice that for the previous year – and $22bn of tax. That’s a 34% effective rate – which we’d normally say is around what we’d expect (much higher than a normal company, because oil/gas extraction tends to be subject to special taxes).

Nothing surprising.

No figures yet on how much of that $22bn of tax will be paid in the UK, but it’s likely very small. Why? Because only 5% of Shell’s business is in the UK. The rest is abroad, and we don’t tax that.

Before 2009, the UK *did* tax foreign profits, but with a complex tax credit system to stop anything being taxed twice. Why did the UK abandon that, and move to an “exemption” system where we almost never tax foreign profits? A mixture of:

- A series of daft CJEU decisions made it difficult and perhaps impossible in practice to operate a credit system without breaking EU law.

- The credit system was *very* complicated, and it’s unclear it ultimately raised more tax.

- For these reasons, other countries had dropped the credit system, and the UK government wanted to be “competitive”

So there is nothing surprising about only around $1bn of the perhaps $22bn total Shell tax bill being paid in the UK. Nothing to see here. Move along.

Except…

These are not normal times. This is not a normal level of profit. Shell made twice as much profit in 2022 as in 2021, but not by being twice as clever. Shell simply is benefiting from the same high energy prices which are hurting households and businesses across the world. There is an obvious political case for rebalancing that equation, and redistributing some of Shell’s winnings back to the people who lost the great 2022 energy game (us).

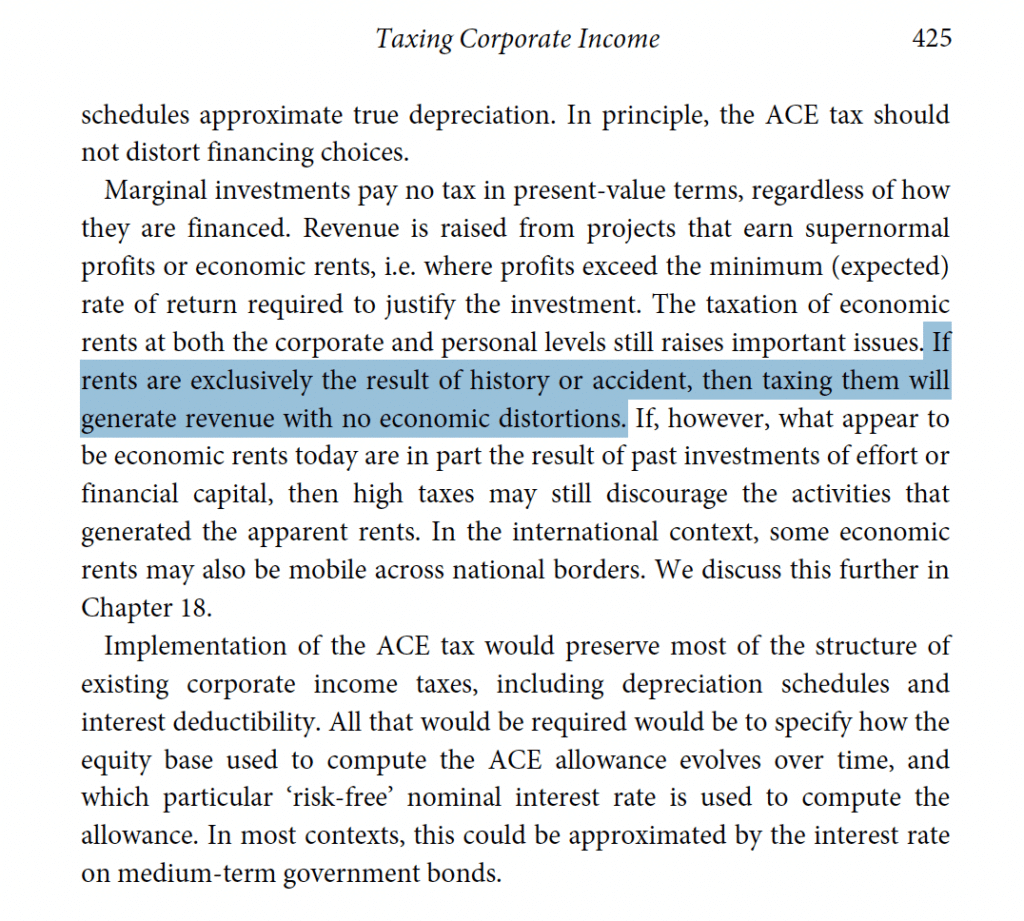

Often these kinds of populist political arguments have large economic and tax policy downsides. In this case, it’s different. Shell’s profits aren’t just normal profits – they’re “economic rent”. Shell is – by pure accident – making a return which doesn’t just exceed its costs, but exceeds the normal return it would expect for the risks that it runs. In other words: a “windfall”.

Standard economics and tax policy says we absolutely *should* tax economic rents that arise by accident. And because those profits arise by accident, that shouldn’t deter investment, or create economic distortions. Here’s what the Mirrlees Review – the bible of conventional tax policy – says:

I’d conclude:

- Shell is making a windfall profit.

- The fact Shell’s effective tax rate remains a fairly typical 34%, when its profits are super-normal, tells us that the windfall profit (Shell’s economic rent) is not in fact being taxed.

BP

Looks like a bumper year for BP:

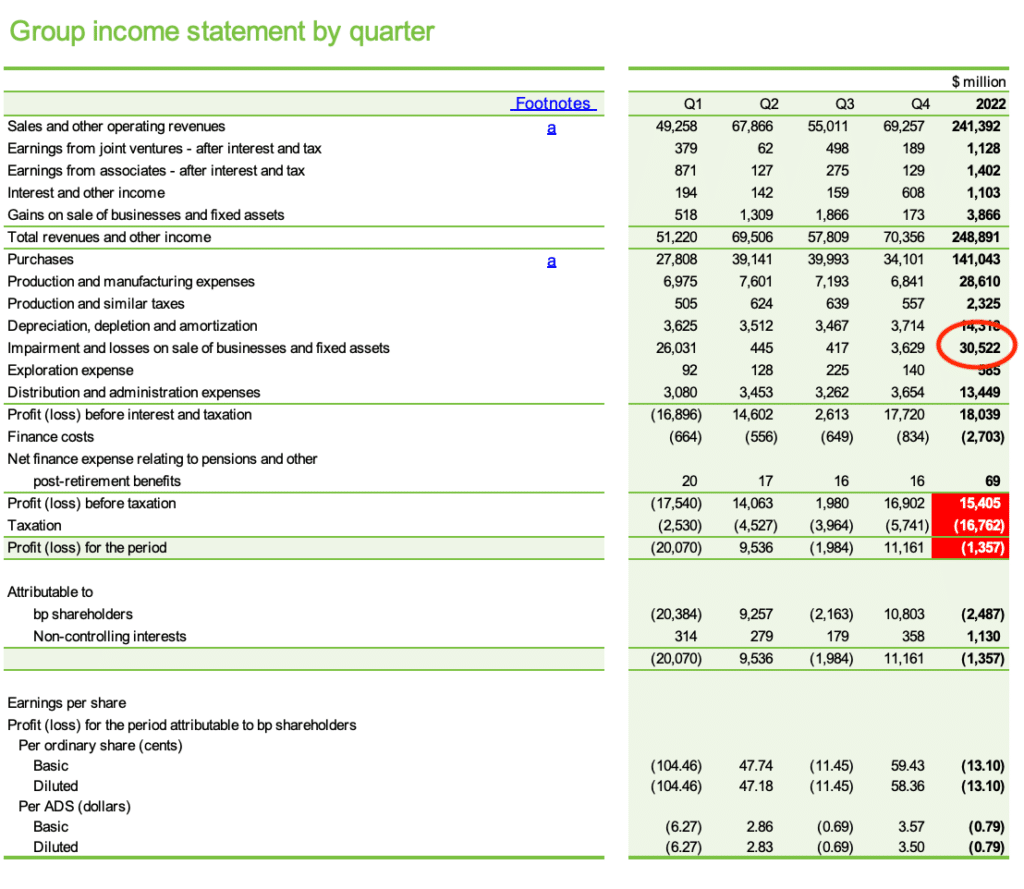

But, looking at BP’s quarterly results in detail, that reported $28bn profit is the “underlying replacement cost profit” – a non-GAAP figure (i.e. not a standard accounting definition of profit). The standard GAAP figure shows a $15bn pre-tax profit, then $17bn of tax – so a post-tax *loss*:

How can actual profit be negative, but underlying profit be $28bn? Largely because of BP’s forced sale of Rosneft, which lost them around $25bn (which goes into the $30bn figure I’ve circled above).

The Rosneft loss is absolutely a real economic cost for BP, but there’s no tax relief for it (in the UK or, I expect, anywhere else). So it massively reduces BP’s profit, but doesn’t reduce BP’s tax bill. Which is why there’s $17bn of tax on a $15bn profit.

But let’s pretend the Rosneft loss didn’t exist, and do the same calculation we made for Shell – is BP paying an appropriate level of tax on that underlying $28bn of profit?

$16bn of tax on $28bn of profit = a 61% effective tax rate. That’s much higher than Shell’s 34%, and also much higher than BP’s typical effective tax rate (which averages at around 40% in recent years, but that disguises some wild variations).

Why is the rate so high? I’m not sure. I can’t see any details of the tax calculation in the BP papers published today, although it does indicate that only $2bn comes from the increase in the UK windfall tax/energy profits levy. Update: a commentator below suggests the reason may be a Q3 negative mark-to-market on gas hedges resulting in a P&L loss that’s disregarded for tax purposes, therefore increasing the ETR. That seems plausible to me.

I’d conclude from this:

- Did BP make a massive windfall profit from its underlying energy business? Absolutely yes.

- But did BP also make a massive “reverse windfall” loss from Rosneft? Again, yes.

- It doesn’t seem fair to tax the windfall profit as if the loss wasn’t real. Because it was.

- Even if it hadn’t made the big Rosneft loss, it’s still unclear whether we could say BP isn’t paying an appropriate level of tax on its windfall/economic rent.

So what to do?

The UK is already somewhat taxing windfall profits with its “energy profits levy”, which takes the total tax on UK oil and gas production to 75%. That tax is badly flawed, but that’s not the main problem here: UK oil and gas is only a small part of Shell’s revenues (and a larger, but still quite small, part of BP’s revenues).

Mostly Shell’s rent is being untaxed because it’s not the UK’s to tax, and other countries are not taxing it. The windfall taxes that have been introduced have been relatively modest.

Which prompts the thought: if nobody else is taxing Shell’s economic rent, perhaps the UK should? A temporary and absolutely one-off return to worldwide taxation for a one-off windfall tax.

The UK has had successful windfall taxes in the past, and many people would say this is a clear case of a set of exceptional circumstances resulting in a one-off profit that isn’t deserved, and should be taxed. And a proper windfall tax is retrospective: we wait and see just how much of a windfall the energy companies made, and then tax it after the event – which prevents any possibility of avoiding the tax.

There are two significant counter-arguments:

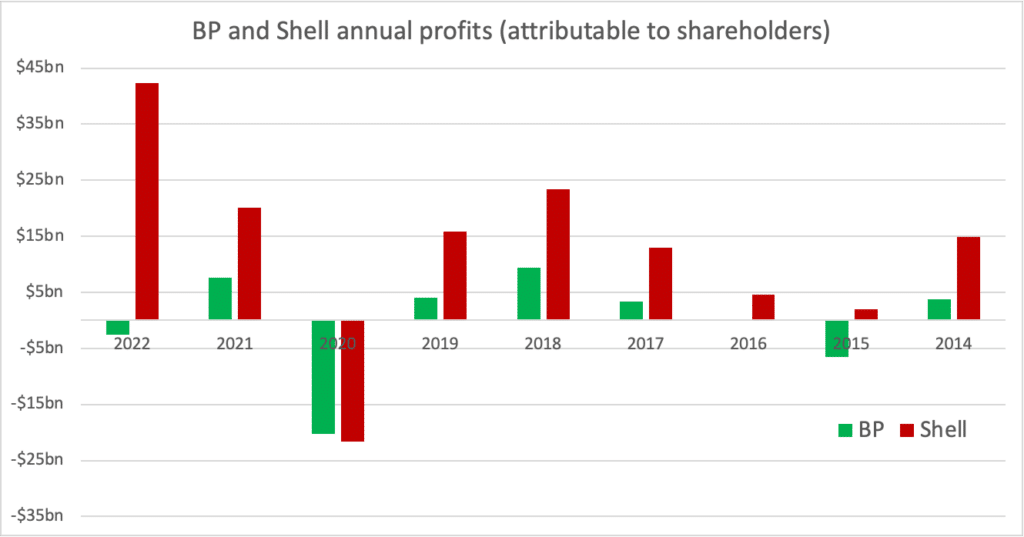

First, that energy prices are naturally cyclical, and so energy companies make big losses in bad years (2020) and big profits in good ones (2022):

The sheer scale of Shell’s 2022 profits make that a less persuasive argument.

Second, that if the UK take so extraordinary a step then we should expect BP, Shell and other large multinationals to run away, and move their holding company and headquarters elsewhere. That is much less of a risk if other countries introduce worldwide windfall taxes – that might yet happen, although the windfall taxes announced to date have tended to be territorial. But the really key question is whether people see any extraordinary new windfall tax as a one-off, never to be repeated, or the start of a series of similar taxes. The two previous UK windfall taxes: the 1981 bank deposit tax and the 1998 utility windfall tax, were promised to be exceptional one-offs, and those promises were kept. How credible would such a promise be today?

A retrospective worldwide tax on UK headquartered energy companies would unprecedented, highly controversial, and is not without risk – but in these serious times it should be given serious consideration.

I’ve written more about how such a tax could be designed.

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – just so people can clearly see the more technical comments. I will also delete comments which are political in nature

Photo by Stable Diffusion 2.1: “beautiful photo of an oil rig in the ocean, dramatic sunset, dramatic lighting”

11 responses to “Is it right that Shell and BP made $70bn profit in 2022 but pay little tax in the UK? Yes. And also, no.”

Just a quick point on the BP ETR, a quick scan of the materials suggests the issue is in Q3 with a dip in revenue around a $10bn mark to market on gas hedges (but not the underlying contracts) given the high gas price. With this unrealised “loss” being unrelieved you get a Q3 tax charge despite a book pre-tax loss. This effect is eliminated in the underlying figures.

That is an excellent spot – thank you!

Will somebody please put the Labour party straight, deducting the costs of dismantling infrastructure & site restoration is NOT a loophole. The profits of an oil or gas field can only be finalised at the end of its life once all costs have been incurred. Consequently, it can be said that any tax refund obtained at the end of life is a refund of tax overpaid in the earlier years.

How about a windfall tax on the additional profits made by umbrella manufacturers after a rainy season? Balanced, of course, by a tax credit given when they fall into losses because of a drought. And as for ice cream manufacturers…

The obvious risk (to me) is that Shell would abandon investment in activities that fall within the Uk’s remit for investment in jurisdictions with more generous taxation levels.

Well argued piece – thanks. Minor typo in this line I think “companies make big losses in bad years (2020) and big profits in good ones (2020)”. Last number should be 2022.

Thanks!

The existing structure for the OECD project on minimum global tax seems like the appropriate place to agree a global windfall tax on energy.

Perhaps I missed it but I don’t see any segmental analysis on how much of Shell’s revenue or profit comes from the UK or how much tax is paid in the UK. We can be sure that it is a small fraction of £65 billion and £22 billion. As for the UK windfall tax, it is buried but in one place they refer to a cost of “£802 million relating to the UK Energy Profits Levy” for 2022. So that is a small fraction of their overall tax cost.

Second, it is not just the UK that is taking action to tax windfall profits. Some European counties have their own windfall taxes already, and there is a proposal at EU level

for an energy “solidarity levy”. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/09/30/council-agrees-on-emergency-measures-to-reduce-energy-prices/

Not enough, I am sure, but better than nothing.

This is only the “announcement” – the actual Annual Report for 2021 was published on 2022/03/10, so this year’s is presumably a month away.

Note 5 at https://reports.shell.com/annual-report/2021/consolidated-financial-statements/notes/segment-information.html shows UK being 8% of turnover within Europe 30%, USA 28%, Asia&Africa 33%, Other Americas 8%.

CNN says approaching 40% from LNG trading, which per Shell website is based in Singapore (17%? tax rate) and Dubai (0%?). That suggests that the rest is taxed fairly heavily to get up to 34% ETR.

Thanks, Richard. Shell does publish country by country data: eg for 2021: https://reports.shell.com/tax-contribution-report/2021/our-tax-data/our-tax-data-by-country-and-location.html

Overall, in 2021, $5 billion of tax on $26 billion of profits from $630 billion of revenues.

In 2021, the UK had over 6,700 employees, there were third party revenues of almost $23 billion, and related party revenues of over $60 billion. Somehow they made a loss in the UK of almost $1 billion, and UK tax was a negative number. Similarly, in the US, the 15,000 employees made $6 billion of profits from $169 billion of revenues but the tax was also negative..

And the 111 employees in Switzerland make over $1 billion of profit from $2 billion of revenue but only $175m of tax was due. And $2 billion of tax was paid in Oman on $3 billion of profit from $8 billion of revenues. (Oman also seems to do well in 2020.)