Tax Policy Associates has new data suggesting that around 26,000 businesses are stalling their growth for fear of hitting the VAT threshold.

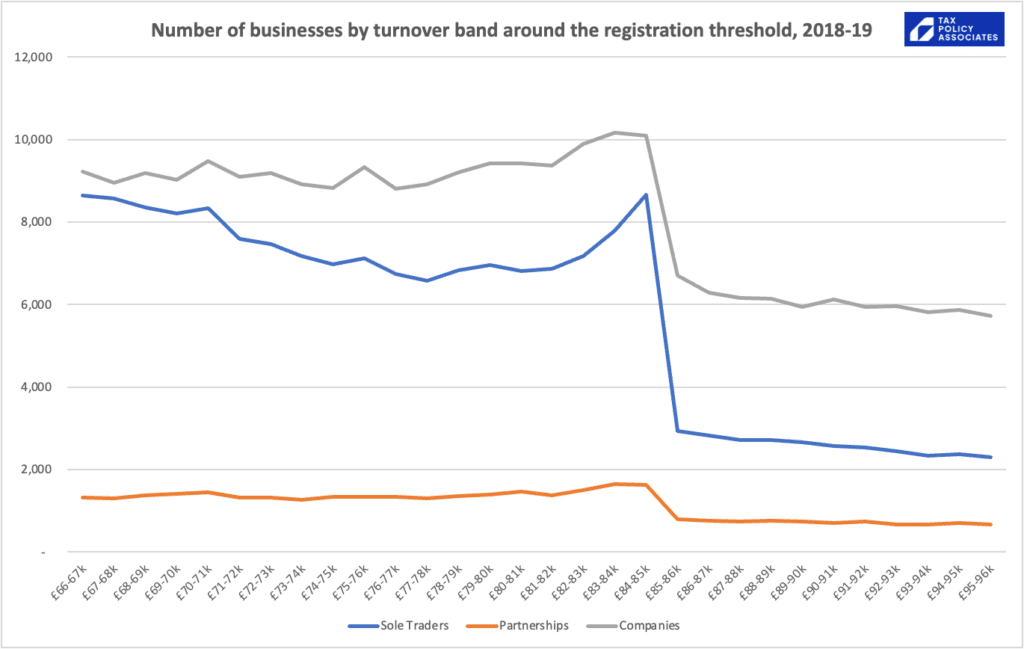

This chart deserves more attention:

It shows the number of businesses at each turnover level in 2018/19. You’d expect a reasonably smooth curve, falling from a large number of small businesses on the left side, down to a smaller number of larger businesses on the right. But we don’t see that at all – we see a massive cliff edge right on the £85,000 VAT registration threshold – the point at which they’d need to charge 20% VAT.1The HMRC FOIA response is here, and our analysis preadsheet here.. The FT covered this here – apologies for not writing it up sooner.

What does that mean? It means that companies are holding back their turnover – slowing and stopping growth – to avoid having to charge VAT.

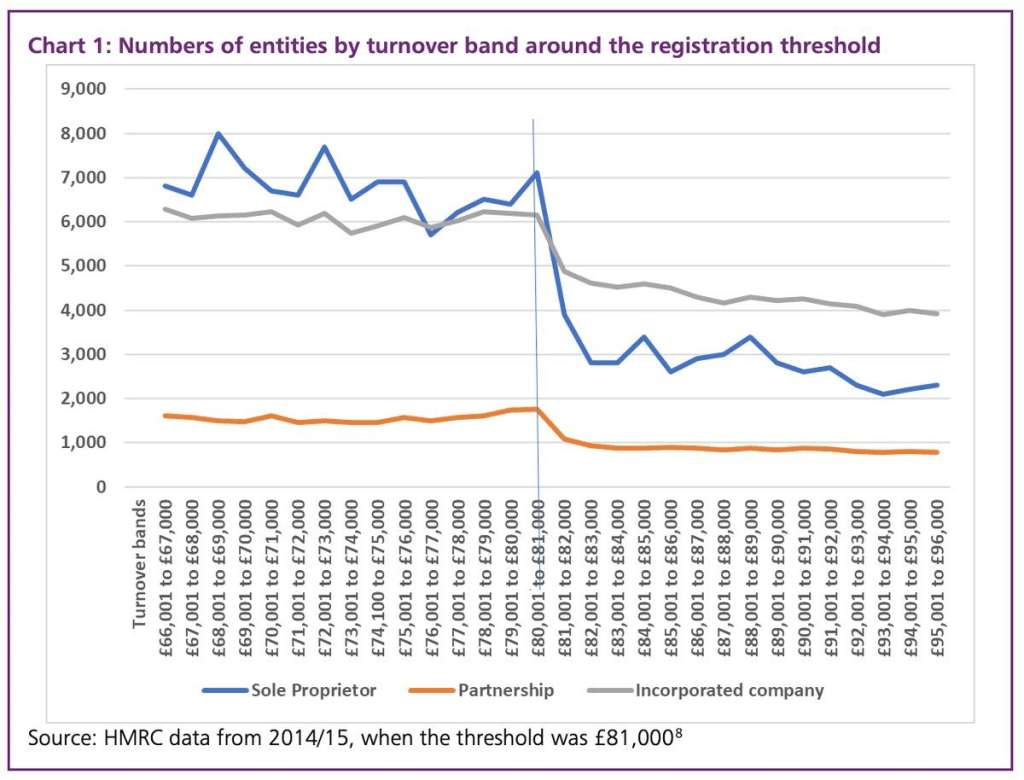

That looks much worse than the data HMRC published for 2014/15, which I commented on here.2from the OTS review of VAT in 2017.

Worse in two ways: more bunching before the threshold, and a steeper decline afterwards. About 3,500 companies per £1k turnover band go “missing” (compared to about3I’m having to eyeball that, as we don’t have the raw data for 2014/15, only the chart 2,000 in 2014/15) and about 4,500 sole traders (around 3,500 in 2014/15). Why? I don’t know. 4An obvious response is “Brexit”, but I don’t think that can be right. Brexit certainly made things more complicated for cross-border sales, but only after legally effective exit on 1 January 2021. Some firms adapted their business models ahead of 2021, but those were generally larger firms. And in this case it would be odd for small firms to suppress their turnover (i.e. make less money!) or hide income (commit criminal tax evasion!) before it gave them any advantage. So I can’t immediately see why there would be any Brexit effects as early as 2018/19. However, there could be significant Brexit effects from 1 January 2021, meaning that the effect could plausibly be much worse today than it was in 2018/19. One plausible cause is the significant limitations placed on the VAT flat rate scheme after 2015-16.5Many thanks to Damian McBride on Twitter for suggesting this. The flat rate scheme was restricted for good reason – it was being widely abused – but it would be good to have some assurance that the cure is better than the disease… right now I don’t know

Why do we see the cliff-edge effect? Because businesses don’t want to have to charge VAT – and have to raise prices by up to 20%.6“up to” because many businesses will be able to recover significant input VAT. For example, if I run a restaurant with £100k of turnover, £20k of ingredient costs (plus VAT) and £30k of rent (plus VAT) then I’ll owe HMRC 20% of £100k but be able to recover 20% of £20k and 20% of £30k. My net VAT bill is therefore £20 – £4 – £6 = £10. So becoming VAT registered is actually costing me 10% of my turnover, not 20%. Contrast with e.g. if I’m a tax consultant operating out of my house with few VATable expenses – my VAT cost is then likely close to 20%. Of course they could instead eat some of the VAT cost in the form of reduced profits – but in most cases their profits will be too small to cover more than a teensy bit of the VAT costCompliance hassle is also a factor, but evidence suggests much less important than the cold hard cash cost.

So they suppress their turnover. If the 2022 Warwick paper is correct, this is decelerated growth rather than failure to report income/VAT evasion. I wrote about that more here.

How? For example: plumbers don’t take on an apprentice. Contractors stop working in February. Accountants work separately rather than combining into one business. What effect is this going to have on overall UK productivity? I’m not an economist, but it doesn’t feel fantastic…

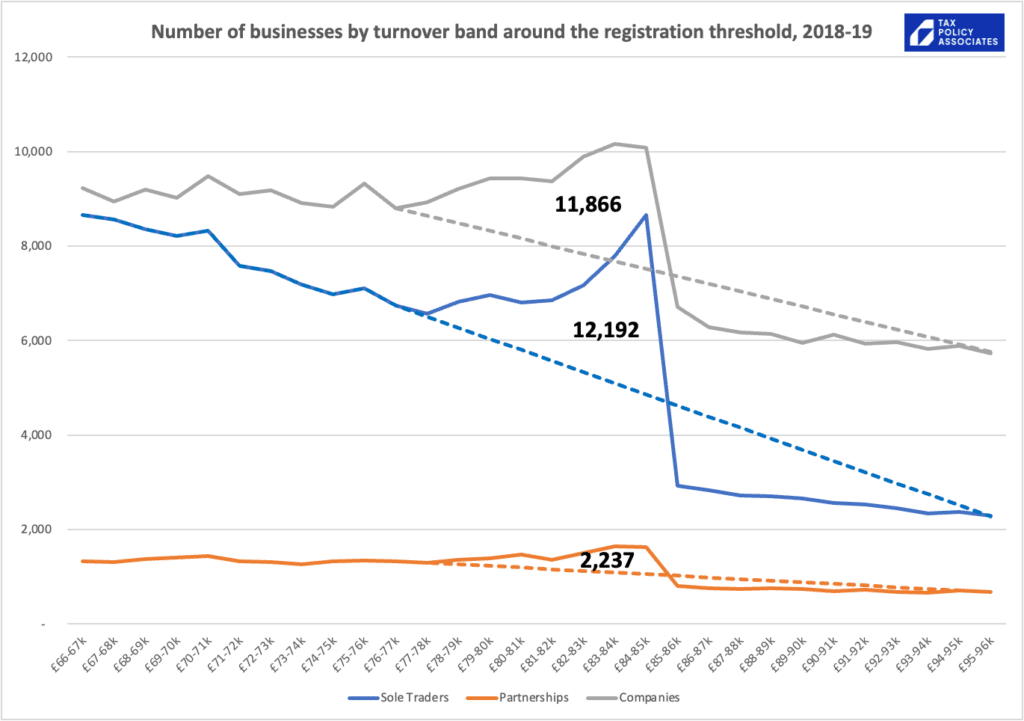

We can approximately measure the effect by measuring the size of the “bulge” before the cliff in the chart, and counting the number of firms in it:

That’s about 26,000 businesses whose growth has been stalled by the VAT threshold.

I continue to think that this is one of the most critical UK tax policy problems.

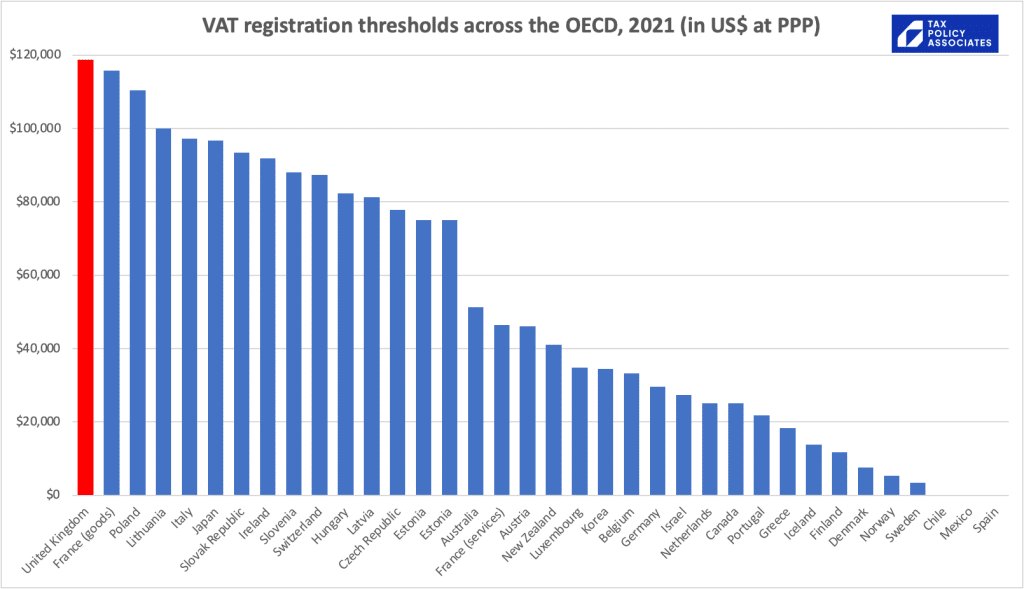

How does the UK’s registration threshold compare with everyone else?

The UK has the highest registration threshold in the world:7The chart doesn’t include the US because, whilst many States apply sales taxes with thresholds as high as $500,000, they’re conceptually very different from VATs. The rates are much lower (averaging around 6%), they don’t apply B2B, and the tax bases are relatively limited. Singapore also isn’t on the chart, as it’s not an OECD member – it has a high GST registration threshold of SGD 1m/year, but that’s much easier in a country where the tax/GDP ratio is less than half the OECD average

When the threshold is as low as $30,000, it becomes unrealistic for businesses to suppress their growth to keep below it. Only the most micro of micro businesses won’t charge VAT, and everyone else is on a level playing field.

Why is this a problem?

One way to view this is that the UK is losing out on VAT revenue. I think that is to miss some much more important issues.

It doesn’t seem fanciful to think that some of the 26,000 firms that are holding their growth below the VAT threshold might have thrived if they’d gone beyond it. Hired more employees, grown from micro companies into small, then medium, then – who knows? – become large businesses. What is the impact on macroeconomic growth of some companies’ growth simply stalling?

And could this be part of the productivity puzzle? The effect of staying below the threshold is that businesses never grow past one employee… but there is good evidence that businesses with more employees are more productive. There is an excellent article making exactly this point from the Adam Smith Institute (they seem to have been the first people to write about the issue – full credit to them).

I’d love to see an economist undertake some analysis on whether there is a material macroeconomic impact from the effects shown by the HMRC and Warwick data.

What’s the solution?

Here are three bad solutions:

- Raise the threshold dramatically. That doesn’t remove the problem; it just moves it to a higher turnover level. It would also be extremely expensive – every £1,000 of increase in the threshold costs approximately £50m in lost VAT revenues.

- Reduce the threshold to an OECD average. That in principle fixes the problem, but at that cost of requiring every small/micro business to apply VAT at 20% overnight. That doesn’t seem wise or politically realistic.

- Reduce the threshold a bit. I fear even (say) a £5,000 cut in the threshold is too politically difficult, and it would just move the problem elsewhere.

And a boring solution, which is probably what’s happening at the moment:

- Freeze the £85,000 registration threshold over time. Inflation is 10% this year; if we then assume 4% average inflation for the next ten years8I am also assuming politicians can resist heavy lobbying to stop the freeze. You may feel that is like assuming a spherical cow., then in real terms the threshold will be £52,000 by 2034, and £35,000 by 2044. So a partial solution – but if the current cliff edge is a real economic problem, waiting twenty years to solve it feels like an inadequate response.

What we need is a way to eliminate the dramatic “cliff-edge” effect that takes less than twenty years, doesn’t just move the cliff-edge elsewhere, and is neutral in government revenue terms. And one benefit of Brexit is that we have the freedom to change VAT however we like.9mostly

Here’s one potential idea:

Instead of a dramatic threshold, that takes VAT from zero to 20%, let’s smoothly phase it in. So, for example, at £30,000 VAT would be applied at 1% (and input tax recoverable at 1%), with the rate increasing bit-by-bit until by £140,000 VAT would fully apply at 20% (with the intention that the overall effect is revenue-neutral). The OTS proposed further investigation of such a system back in 2019, but I don’t believe it went any further.10See paragraph 1.29 here

This would once have been impractical, given that the complications it creates for business customers of a business applying (say) 7% VAT. But all VAT returns will soon be digital – so that element now feels like a relatively trivial technical problem, rather than a difficult human one.

I shouldn’t understate the challenges. One particularly difficult element is how you decide in advance what rate a business should charge. Easy(ish) for an established business with a consistent quarterly turnover. Hard for a new business, or one that’s growing or shrinking unpredictably.

You could sidestep that difficulty, but achieve an economically identical result, with a rebate system. Everyone charges 20% VAT from (say) £30,000 of turnover, but 19% of that is rebated for £30k businesses. The rebate drops as turnover increases, vanishing entirely at (say) £140k. If you pay the rebate quarterly in arrears then that removes the need to predict future turnover – that does, however, create a three-month cashflow problem for small businesses, and trying to solve that problem just runs into the predictability issue again. Rebate systems also can create tricky issues with cross-border supplies – how do we give foreign suppliers a rebate? And if we don’t, how can we avoid distortions and unfairness (and potentially WTO/GATS difficulties)?

And we shouldn’t minimise the political difficulties with any proposal which increases prices/reduces profit for £30k-£85k businesses. I don’t expect the immediate beneficiaries (the £85k-140k businesses) would call many demonstrations in support. So it would take a brave Government, which recognises a potential brake on growth and is willing to court unpopularity to release it.

I’d love to see this issue becoming part of the public tax debate. I can’t lie: solving it will be really hard, and require input from people with expertise that I don’t begin to have. Specifically, economists need to confirm the intuition that this is a serious problem for the UK economy, and compliance specialists (in HMRC and the private sector) need to work up a solution that doesn’t cause more problems than it fixes. It’s possible we end up concluding that the current situation is bad, but any radical solution would be worse, and we just have to sit tight for ten/twenty years and let inflation erode the VAT threshold to something sensible.

All of this would need very serious thought, and I am absolutely not saying I have all the answers. Very possibly I have none of the answers. I do, however, believe I have a question.

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area). I love reading emails thanking us for our work, but I will delete those when they’re comments – just so people can clearly see the more technical comments. I will also delete comments which are political in nature.

Image by DALL-E: “a colourful set of equal-sized cubic children’s wooden building blocks with the letters VAT (in order), on a wooden table, digital art”

- 1

-

2from the OTS review of VAT in 2017

-

3I’m having to eyeball that, as we don’t have the raw data for 2014/15, only the chart

-

4An obvious response is “Brexit”, but I don’t think that can be right. Brexit certainly made things more complicated for cross-border sales, but only after legally effective exit on 1 January 2021. Some firms adapted their business models ahead of 2021, but those were generally larger firms. And in this case it would be odd for small firms to suppress their turnover (i.e. make less money!) or hide income (commit criminal tax evasion!) before it gave them any advantage. So I can’t immediately see why there would be any Brexit effects as early as 2018/19. However, there could be significant Brexit effects from 1 January 2021, meaning that the effect could plausibly be much worse today than it was in 2018/19.

-

5Many thanks to Damian McBride on Twitter for suggesting this. The flat rate scheme was restricted for good reason – it was being widely abused – but it would be good to have some assurance that the cure is better than the disease… right now I don’t know

-

6“up to” because many businesses will be able to recover significant input VAT. For example, if I run a restaurant with £100k of turnover, £20k of ingredient costs (plus VAT) and £30k of rent (plus VAT) then I’ll owe HMRC 20% of £100k but be able to recover 20% of £20k and 20% of £30k. My net VAT bill is therefore £20 – £4 – £6 = £10. So becoming VAT registered is actually costing me 10% of my turnover, not 20%. Contrast with e.g. if I’m a tax consultant operating out of my house with few VATable expenses – my VAT cost is then likely close to 20%. Of course they could instead eat some of the VAT cost in the form of reduced profits – but in most cases their profits will be too small to cover more than a teensy bit of the VAT cost

-

7The chart doesn’t include the US because, whilst many States apply sales taxes with thresholds as high as $500,000, they’re conceptually very different from VATs. The rates are much lower (averaging around 6%), they don’t apply B2B, and the tax bases are relatively limited. Singapore also isn’t on the chart, as it’s not an OECD member – it has a high GST registration threshold of SGD 1m/year, but that’s much easier in a country where the tax/GDP ratio is less than half the OECD average

-

8I am also assuming politicians can resist heavy lobbying to stop the freeze. You may feel that is like assuming a spherical cow.

-

9mostly

-

10See paragraph 1.29 here

27 responses to “Is VAT stopping 26,000 businesses from growing? More on the VAT growth brake.”

Something to be said for cutting the registration threshold to a very low level, and offsetting it by lowering the rate for 19% small profits corporate tax (maybe to zero, would make it politically saleable)?

Yes, it also creates incentives to split activity into separate businesses, but at least going over the £50k profit threshold would only see profits marginal profits above that threshold subject to corporate tax (until the £250k threshold is crossed).

Wouldn’t it be a cleaner solution to just apply VAT to anything over the threshold – eg £85000 turnover – no Vat, £86000 turnover, you just pay VAT on the £1000 you’re over by. Maybe use one of the other solutions in tandem to reduce the government income hit. This way, you don’t end up with stupid situations where contractors earning £110,000 get less take home pay than one earning £80,000.

That would be amazingly expensive – £30bn or more. Also creates a big incentive, just as at the moment, for people to fragment their business into multiple <85k businesses...

Why not have a timed transition window

When you cross 85k, either

– [3-5] y to pay zero vat until 120k of revenue

– [3-5]y to pay VAT only on the marginal revenue above 85k?

problem with timed transitions is it creates an incentive to close/reopen businesses to restart the clock. I think any solution has to be “clean” and apply to everyone…

Why even have a sales tax? Or is that too maverick? I have never understood why most of the world follows this system and it strikes me as inefficient. Why tax sales when you could just tax profits (or income tax) at a higher rate?

I agree with all your points but for me the flipside to consider is by having a sizeable (£85k) threshold you are encouraging entrepreneurship by giving small businesses a competitive edge in their pricing (I.e. a soletrader plumber can undercut Pimlico due to the VAT differential).

The other factor is the negative impact on consumer spending if more businesses start charging VAT – takeaways, hairdressers, tradesmen will all get 20% more expensive with no benefit for the consumer.

Its a tough one and I’m not sure what the answer is, but my view has always been scrap it or mandate it for everyone (similar to your thoughts). A stepped VAT rate as you say is probably the ideal but the administration would be complex and hard to understand for many business owners.

Well worth reading the Mirrlees Review – there is a consensus that VAT has significant advantages over profits taxes in terms of not deterring investment, and robustness vs avoidance. The sums also don’t add up – VAT raises £140bn and corporation tax @19% raised £60bn. Just not possible to raise £140bn more from taxing profits.

I went freelance three years ago, and work as a sole trader in the charity sector. I am well under the threshold, and that is definitely a benefit for me, both in terms of administrative simplicity, and in terms of pricing my services (particularly as most charities are not VAT registered).

In terms of the threshold, I can see the logic to it coming down somewhat, but a reasonably high threshold does mean that (most) sole traders are not having to grapple with VAT at start up (which is one of the most difficult stages for a business) – i.e. if the threshold is too low, then it may address the cliff edge issue (which is mainly a price one) but simply replace it with a discouragement of new businesses (where the admin factor is much more significant).

The other option which surely is worth a look at is lower VAT rates? Its a very regressive tax for consumers. Lower rates would then mean that the price impact of crossing the VAT threshold is less severe. In contrast, tiered VAT rates sounds like a truly awful solution – why would be want to make taxes more complex? And anything that relies on – “it’s all digital anyway so it doesn’t matter if it is complex” – surely should ring alarm bells…

Lower rates would be extraordinarily expensive. Broadly each percentage point cut will cost £8bn.

It’s also not as regressive as you think – it’s mildly regressive with respect to income, but mildly progressive with respect to consumption – see https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/09chap10.pdf

Having worked with many small businesses over the years I have had this discussion on numerous occasions.

My view has long been that a low threshold is preferable. It avoids the severe impact on a small business, especially a service-sector B2C business, of straying over the £85k threshold. With little input tax and perhaps local competition, that business can suffer a loss (or perceived loss) of over £15,000. Hence the bunching in turnover.

I like the tapered approach. I would use a less nuanced taper. For example, up to £25k turnover, an effective VAT rate of 5%; £25k-£50k an effective rate of 10%, etc. This would still require innovative software solutions and accuracy record-keeping. But it would soften the impact of exceeding the threshold. AND, it would teach the population that, “if you are in business, you register for VAT.”

Further, disaggregation disappears!

These three ideas all used together:

1.. Your rebate scheme.

Plus:

2. Monthly VAT for small/new traders. (With each month counted as a tax period.)

Plus:

3. Rebate paid back within 3 days of submission.

I see a few people mentioning it, but a big factor here is VAT was designed around material businesses and more and more of our economy is composed of services. VAT as stands is a subsidy on material businesses (and ecologically unsound on that basis). Of course, in damaging services businesses some would say we’re helping productivity (because Baumol) but at the same time it’s a negative because we damage the sectors we have some advantages in – and that’s the real heart of our productivity problems, stunted economic activity and not just at the threshold.

I was involved in VAT when the original threshold was introduced. The problem was recognised even then & was, I recall, why the threshold was set relatively high compared to the rest of the EEC (as it was then). It was also recognised that there would be a major temptation to start making cash/off the record sales when businesses approached the threshold. However, at that stage it was such a new tax for the UK, like much of it we essentially adopted a policy of “suck it and see”. (I can’t recall the exact detail of the discussions as I was engaged on VAT applying to food, former purchase taxable goods, finance and later the higher rate).

I agree that your bad solutions aren’t attractive. The sliding scale arrangement seems potentially complicated, and unless IT programmes were available to do the calculations for small traders, I’m not sure how easily they could manage it, especially where they were supplying other registered traders, where the input tax might vary between different suppliers (and pretty horrendous for the VATman trying to assess whether the correct tax was paid).

Thinking about this before I read your whole article (just the headline stuff on Twitter), I confess that I felt that some form of rebate arrangement was probably the only workable answer, as it would enable traders to lower their prices so that the imposition of VAT would reduce the cost to non-registered/exempt/partially exempt customers. Theoretically, you could do it in advance, using previous turnover figures for the level of rebate from day 1 of the scheme. The problem (which applies to the whole proposal, of course), is whatever provides a cash flow benefit to traders equates to a cash-flow loss for the Treasury. In any case, it would be necessary to have an reliable economic assessment that the cost to the Treasury of a rebate scheme would be more than offset by the increased revenue gained from businesses not cutting back as they approach the threshold.

When I had a VAT registered business (£300k t/o) there was a constant pressure to take cash and not charge the VAT – mainly from professional classes. Once, a peer of the realm got his gardener to ask ‘Lord X says, if he pays cash, can he avoid the VAT’!

I suspect lowering both the rate and threshold would increase the tax take, and reduce the ‘black economy’.

I was so interested to see this article, which describes exactly the problem my business has had for the last 8 years or so. And it’s just, sort of DEMORALISING – you start a business, nurture it, see it thrive. And then you have to consciously decide to stunt its growth. Actually we DID register for VAT for 2 years, but we were hemhorrhaging money (we’re a service industry and can’t claim much VAT back)… so we had to shrink and deregister in order to survive.

Two points:

1. We have two employees, so with the cost of living crisis, there is now a squeeze between what we need to earn to live (a rising floor) against that fixed ceiling of the £85k turnover. We’re modest people and don’t need to earn loads, but – ya know – one does wonder how we’re gonna manage.

2. I’m ashamed to say that another aspect of the VAT threshhold issue is our approach to staffing. We would like to employ colleagues properly, sick pay, holiday pay, all that. Instead, we subcontract to self-employed staff who take the money and then pay us a commission (not sure if that technically counts as subcontracting, but you get what I mean). If we employed people directly, all the money they earn would go through our business and we’d be over that threshhold and have to charge VAT. Point is – this has serious consequences for people’s employment status, and means they are far more insecure

Thank you so much for your comment.

As a (now retired) bank manager I worked with small businesses for 30 years. The threshold has always been a problem for growth. Many hundreds of business conversations focussed on this point. The core point for the business owner is always, “can I live decently from my labour charge?” (Within the vat threshold). Note, if your business requires supply/fit of goods (say a boiler) your capacity for personal labour charge diminishes. One way around that is to arrange a deal with the wholesaler through the tradespeople, so that the price of the “goods” is not passed through the tradesperson’s turnover, it’s paid direct by the customer.

No small business has ever been able to lift their prices overnight by 20%without significant risk. “Regulars” just go elsewhere. Any growth plan has to be a jump that adds at least 50% to turnover … which needs to be “Labour based”. The risk is very often simply too great to take.

We introduced VAT because it was a requirement when we joined the Common Market. Now that we’ve Brexited, is there any particular reason why we need to keep it? Raise what we need via other existing regimes, which people are already familiar with. VAT is a bloody awful tax to administer.

VAT replaced purchase tax and a whole bunch of levies and tariffs. Overall, the total level of tax on goods and services is much the same as it was pre-VAT – but the system is much better and easier to operate for taxpayers and HMRC alike. See https://heacham.neidles.com/2022/10/11/four-infographics/ So I’m afraid I disagree!

One consequence of the low VAT threshold on the continent, plus the high VAT rate, is a substantial amount of tax avoidance by sole traders. The effect of reducing the VAT threshold in the UK could thus be an increase in the cash economy. This might be reduced if the level of registration for VAT – and most importantly VAT rebate – is less than the threshold for payment. Or it might not. This is, I suspect an issue for a sociologist as much as for a tax specialist.

that’s a great point, and these kinds of effects absolutely need to be fully through-through before a change is made. The UK does appear to have a smaller undocumented/shadow economy than most of the EU, although the difference is in most cases not great… see https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/734007/IPOL_STU(2022)734007_EN.pdf

Interesting on VAT factor. I’ve read lots of academic micro-SME research recently and found other issues around growth for small businesses…

Growth doesn’t equate to increased profit to put back into the business UNLESS there is rapid growth. Most SMEs probably achieve incremental growth so they struggle to get profit increase. So owners end up with more complex businesses, for limited/ no extra benefit.

Scalability does increase profit because there are no aligned/ increasing resource costs. But scaling is done through tech mainly and not every SME has that capability.

Micro SME owners tend to be more risk averse to finanical risk e.g. borrowing/ taking on additional resources, because there is an intrinsic link between eco and non-eco goals e.g family stability.

Growth/ business development for SMEs up to 85k is highly likely to be down to the SME-owner so they will have a capacity cut-off point and for the reasons above, they cant get additional resources.

And then add on ability to get low cost financing…. etc etc

It’s tough!

The UK’s unusually high VAT threshold is always presented as an advantage to small businesses, which can charge less than competing VAT-registered businesses and don’t have to do VAT compliance (issue invoices, keep accounts, file returns, etc.).

The bunching of businesses below the threshold suggests it is indeed a competitive advantage for these business, but at what cost if it becomes a barrier that inhibits their future growth? Or indeed if it means these businesses don’t keep good business records for other purposes, including income tax or corporation tax.

As the OECD bar chart shows, most EU countries (and most non-EU countries) have domestic VAT thresholds that are substantially lower: effectively zero in places like Spain and Greece, but mostly (including Germany) at around the €30,000 to €40,000 mark, and a handful of exceptions that are higher including Italy, Ireland and France.

Another possibility is setting a level at which a business has to register and provide information (perhaps even recover VAT on inputs) which is lower than the level at which VAT must be charged. I believe Germany is an example.

Although I am also not an economist, I could quibble about the way you’ve drawn trend lines on your third graph: for example, in principle I would expect the number above the dotted line in each case to be about the same as the number below the line. That said, around 20,000 UK business bunched below the threshold (that would otherwise go above) looks about right.

From the graph, we can probably guesstimate the loss of turnover at £20,000 or more so for each business. (I expect that is a substantial underestimate too, but it aligns with the need to increase turnover by about £21,000 to stand still when VAT begins to be charged, ignoring recovery of input VAT). That might be about £400 million of lost economic activity.

Even if it is ten times that, with the UK’s GDP at about £2 trillion, is it moving the needle very much?. The 2017 article at the Adam Smith Institute estimates about £2 billion of additional tax revenue which is in the same ballpark (ultimately I think that is an OTS number). I suppose every little helps but is a few billion here or there solving the UK’s long-standing productivity problem?

Approximately 25 years ago I worked as a vat officer in York. Lots of businesses attempted to stay under the vat registration threshold, most of these were small guest houses who used to close ( allegedly) for a couple of months, say October/ November or February/ March.

Of course the increase in marketing of places such as York as all year/ special occasions visiting venues plus the increase in inflation and the non increase in the vat registration limit has made it much more difficult to remain under the threshold than previously. Remember businesses such as these have little in way of input tax and 20 % output tax on lettings , so a big disincentive to want to be registered whatever the threshold !

I suspect the onset of a cashless society will make keeping under any threshold much more difficult now.

Presumably the type of business makes a difference? If the majority of my inputs are VATable, VAT registration means that the business’s input costs go down by the amount of the now recoverable VAT. There is therefore a positive incentive to cross the threshold. However, if the majority of your inputs are non-VATable (e.g. most services businesses) you get hit much harder. I wonder if, as a policy response, allowing firms in the (say) 80-150k bracket to retain part of the VAT that they collect might be a runner? If you equalized the cash impact by extending the threshold down to (say) 50k you might kill two birds with one stone?

Not all supplies are subject to VAT and so a rebate system only works if that is not the case.

And start up businesses often reclaim VAT ahead of the supplies. If someone is incurring VAT and is in the rebate system, but then grows above that level, how would one adjust so that the inputs in the earlier phase matched the un-rebated outputs in the later phase.

And this is before we even get to B2B supplies and the revenue impacts when A (rebated) makes a supply to B (unrebated).

I agree completely something must be done but I think there is a much easier solution, but it does have some political costs…hence the issue.

This is to start to reduce the threshold. I think about £30k is a good target say within 10 years.

Freezing as you say does have an impact but the level of businesses then registering may not increase as much as expected because of ‘creative’ solutions to make sure the threshold is not increased.

I think also starting to apply some subtle nudges and messages would be a good idea, to try to impact the thinking that being under the threshold by planning is pro business.

In reality it could be considered to be tax avoidance or rather a choice to let others ‘chip in’ towards paying for the essential services we all need.

Paying tax requires a collective commitment to paying in towards things that you and others need. When you have a section of the community that feels it’s wrong for the tax to be paid over through growth and employment etc that’s a problem I think.

Yes having a lower threshold would mean in some cases prices will rise but the impact could be less due to VAT recovery on costs.

And I think from a wider society point of view it would be better for their to be much less VAT reliefs and much more collective paying into the tax club.

This must be matched by appropriate support for the poor etc through the social support system. Relieving VAT on supplies for all to help certain people must be wrong. Classic example – housing. Why should a billionaire be able to buy a new house at the zero rate?

Which politician is brave enough? Hmmm….

As a practising accountant dealing mainly with micro-entities, small partnerships and sole traders, I am aware of many clients who will refuse work/go on holiday etc. to avoid their turnover going above the VAT registration threshold. If they make standard rated supplies of their own or their employee’s labour, they immediately have to increase their turnover by £17K just to maintain their profit and that is assuming the turnover increase does not bring additional costs. I am sure some traders adopt ruses such as getting their customers to supply any standard rated goods and services (builders particularly) and dare I say that some may even look for cash in hand?! Heaven forbid !!