UPDATE: new data suggests the situation is now much worse than suggested in this article. Please see our latest report for the details.

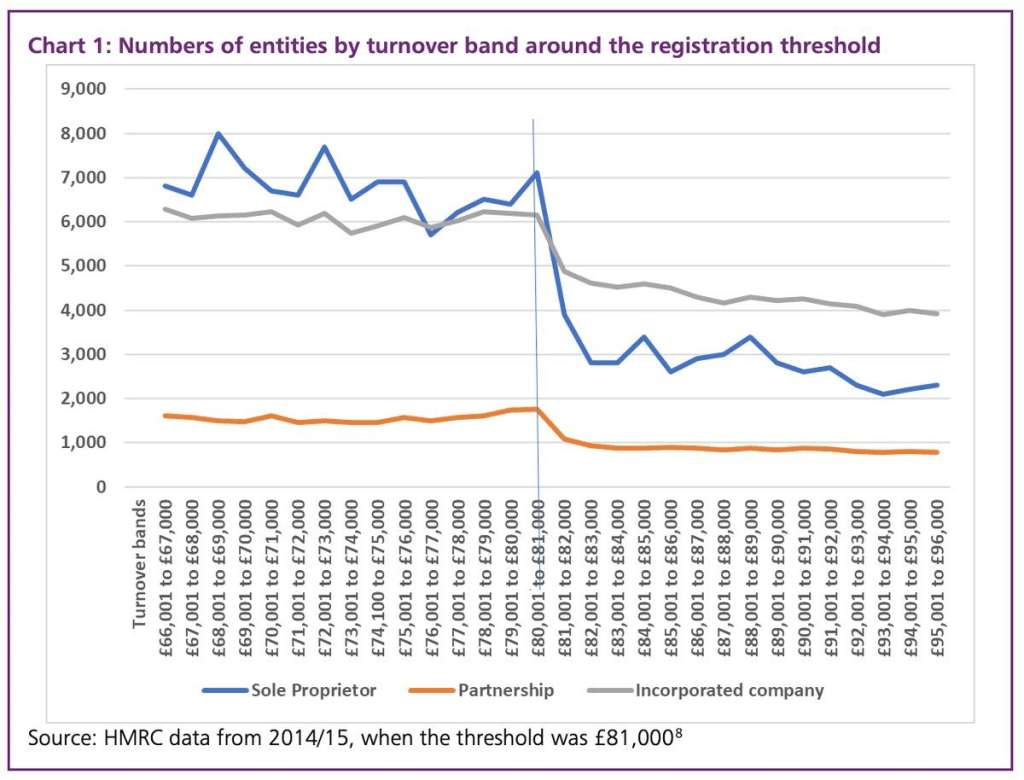

This chart should keep the Chancellor up at night. It shows the number of businesses by turnover band.1 from the OTS review of VAT in 2017

You’d expect a reasonably smooth curve, falling from a large number of small businesses on the left side, down to a smaller number of larger businesses on the right. But we don’t see that at all – we see a massive cliff edge right on the VAT registration threshold. Businesses don’t want to have to charge VAT – and therefore either raise prices by up to2“up to” because many businesses will be able to recover significant input VAT. For example, if I run a restaurant with £100k of turnover, £20k of ingredient costs (plus VAT) and £30k of rent (plus VAT) then I’ll owe HMRC 20% of £100k but be able to recover 20% of £20k and 20% of £30k. My net VAT bill is therefore £20 – £4 – £6 = £10. So becoming VAT registered is actually costing me 10% of my turnover, not 20%. Contrast with e.g. if I’m a tax consultant operating out of my house with few VATable expenses – my VAT cost is then likely close to 20%20% or reduce their profits by the same amount (and the admin hassle is likely also a factor, but I expect a much smaller one). So they suppress their turnover.

This isn’t news – and it got some coverage at the time. But a new paper from the CAGE research centre at Warwick puts beyond doubt that this one of the most critical UK tax policy problems.

New evidence

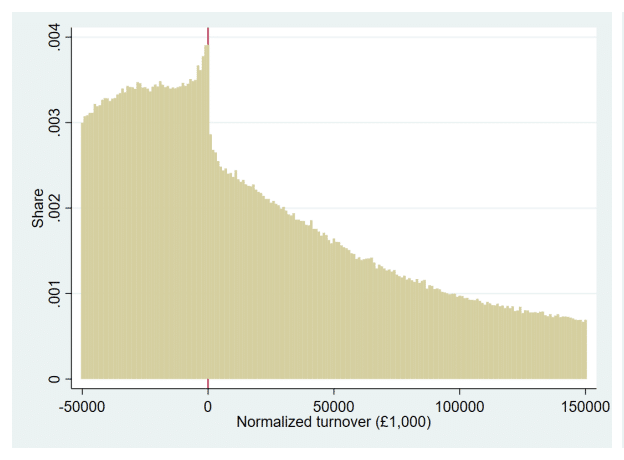

The CAGE team analysed a huge dataset of companies from 2004-2015, with sophisticated controls to minimise confounding effects. They find an even clearer effect than the simple OTS chart above. Here’s a chart showing the proportion of firms that are growing for given levels of turnover:

The ‘0’ point on the x axis and red line running through it) is the VAT threshold. Look how growth peaks immediately before that point and then slumps right on the threshold.

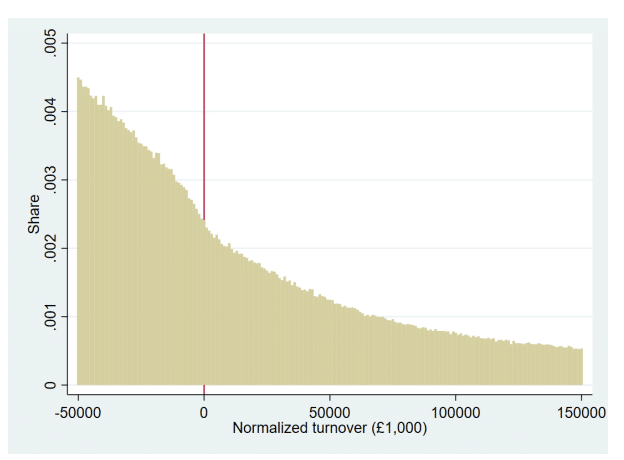

By contrast, shrinking firms show the kind of smooth curve we’d expect:

The smooth shrinkage curves also suggests that the growth cliff-edge is real, and not being driven by failure to declare turnover (i.e. criminal tax evasion). If firms did evade tax to keep below the threshold, then we’d expect to see the same effect in reverse, with a cliff-edge for shrinking firms (so, for example, a firm with £90k of revenue would fail to declare £5k of that, to slip below the threshold before it’s entitled to do so). But we don’t see any evidence of that.

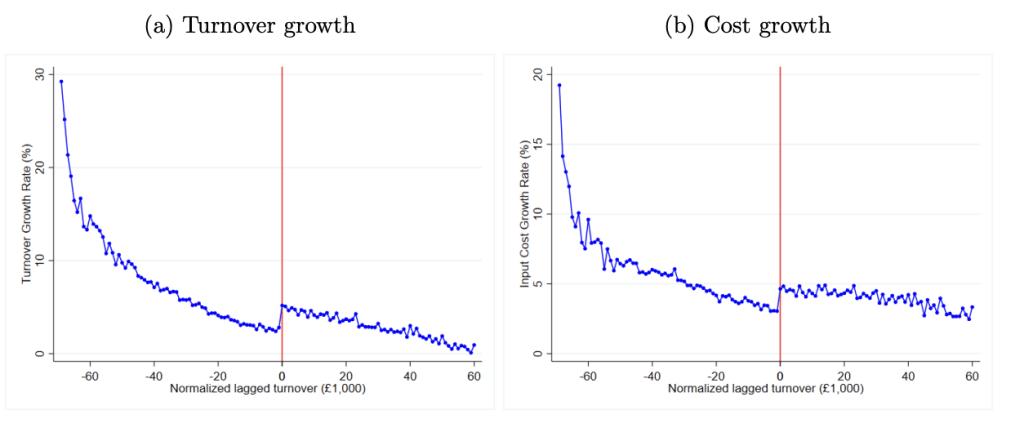

The Warwick team goes further, and look at the impact on rates of growth on turnover and cost:

We can see the brakes being put on – with turnover and cost growth slowing down just before the threshold, but then returning to a higher level afterwards. The fact it happens to cost as well as turnover is important, because this again suggests the effect is real and not just turnover being kept “off the books” (you can’t keep costs off the books without conspiring with your supplier3The one exception here is the apparently (anecdotally) common tactic of builders asking clients to buy their supplies directly, so it doesn’t go through the builder’s books and therefore take them over the threshold. This may be tax avoidance (depending on your own perspective), but in my view it’s not improper and certainly not criminal tax evasion).

How do firms manage their growth?

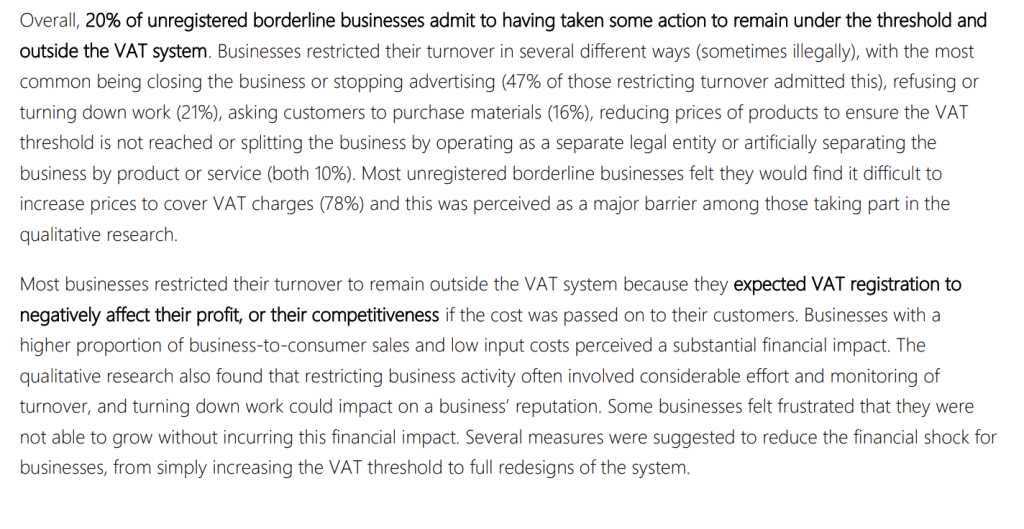

We can get a sense of this in research which HMRC commissioned from Ipsos MORI in 2017. The findings were stark:

If 20% admit to restricting their turnover, I expect the real proportion is significantly higher.

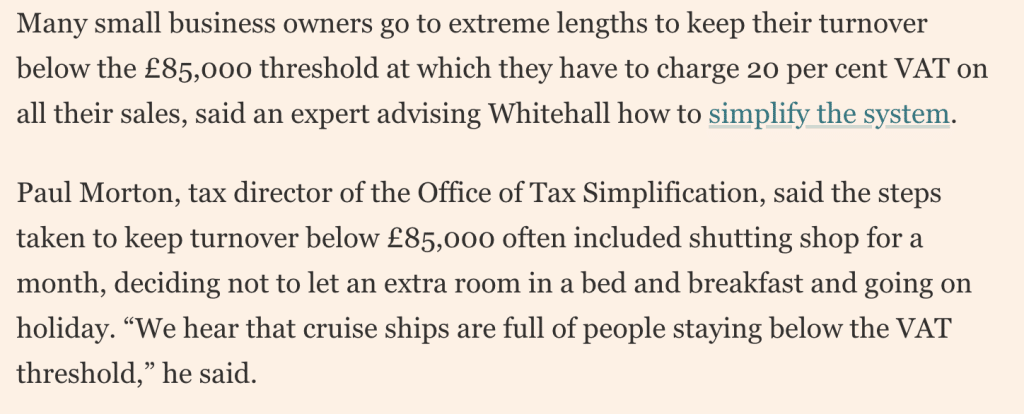

And this accords with the anecdotal evidence I hear from everyone I ask about the subject – whether SME consultants, accountants, coffee shop-owners, builders, builders’ clients… it’s common knowledge that small businesses depress their revenue, most typically by not expanding, not taking on apprentices, and/or cutting back on hours when approaching the threshold. Such as:

Anecdote is not data, but given we already have the data, I find the consistency of the anecdotes compelling.

Are there similar effects elsewhere in the world?

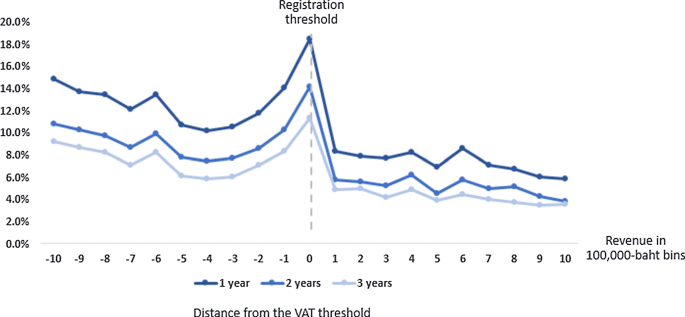

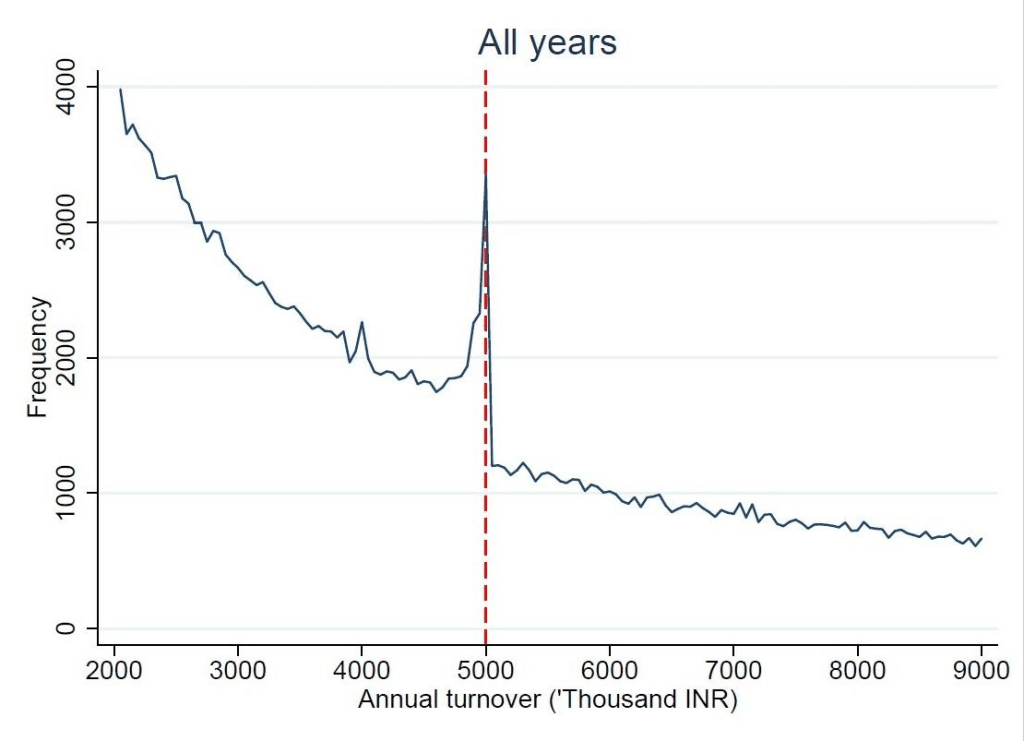

Surprisingly little work has been undertaken in this area, and none that I can find elsewhere in the OECD. However, there has been a detailed analysis of Thai VAT returns, which can be neatly summarised by this chart:

and this chart, from a preliminary analysis of Indian VAT returns:

A similar effect to the UK, albeit more dramatic. Note how the Indian and Thai charts show a much more pronounced peak before the threshold than the UK chart. I would speculate this is because of increased tax evasion compared to the UK – i.e. businesses not just decelerating growth as they approach the threshold, but failing to report sales that would take them over it.

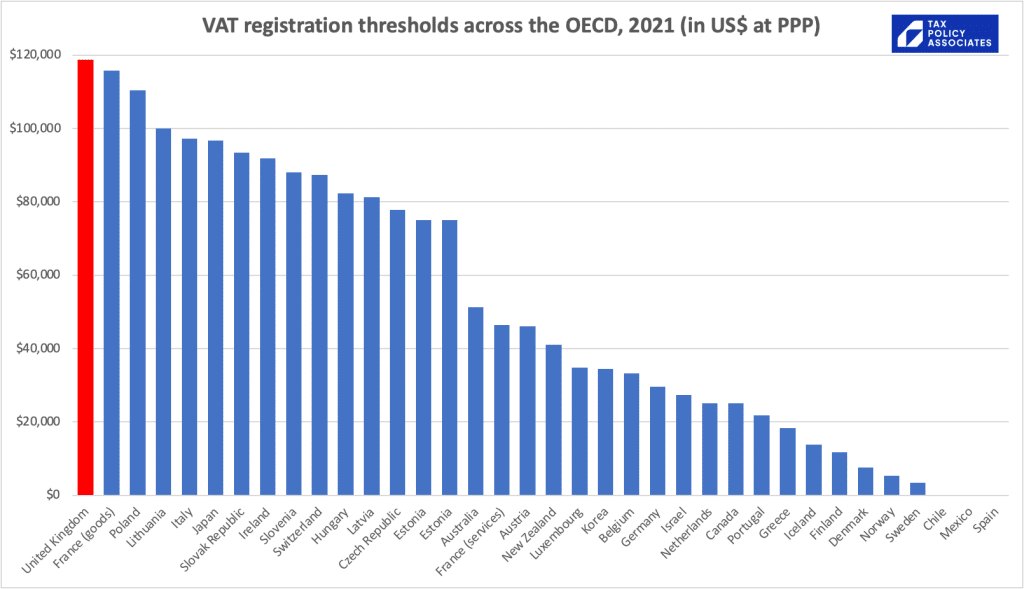

How does the UK’s registration threshold compare with everyone else?

The UK has the highest registration threshold in the world:4The chart doesn’t include the US because, whilst many States apply sales taxes with thresholds as high as $500,000, they’re conceptually very different from VATs. The rates are much lower (averaging around 6%), they don’t apply B2B, and the tax bases are relatively limited. Singapore also isn’t on the chart, as it’s not an OECD member – it has a high GST registration threshold of SGD 1m/year, but that’s much easier in a country where the tax/GDP ratio is less than half the OECD average

When the threshold is as low as $30,000, it becomes unrealistic for businesses to suppress their growth to keep below it. Only the most micro of micro businesses won’t charge VAT, and everyone else is on a level playing field.

Why is this a problem?

One way to view this is that the UK is losing out on VAT revenue. I think that is to miss some much more important issues.

It doesn’t seem fanciful to think that, some of the firms that are staying below the VAT threshold might have thrived if they’d gone beyond it. Hired more employees, grown from micro companies into small, then medium, then – who knows? – become large businesses. What is the impact on macroeconomic growth of some companies’ growth simply stalling?

And could this be part of the productivity puzzle? The effect of staying below the threshold is that businesses never grow past one employee… but there is good evidence that businesses with more employees are more productive. There is an excellent article making exactly this point from the Adam Smith Institute.

I’d love to see an economist undertake some analysis on whether there is a material macroeconomic impact from the effects shown by the HMRC and Warwick data.

What’s the solution?

Here are two bad solutions:

- Raise the threshold dramatically. That doesn’t remove the problem; it just moves it to a higher turnover level. It would also be extremely expensive – every £1,000 of increase in the threshold costs approximately £50m in lost VAT revenues.

- Reduce the threshold to an OECD average. That in principle fixes the problem, but at that cost of requiring every small/micro business to apply VAT at 20% overnight. That doesn’t seem wise or politically realistic.

And a boring solution, which is probably what’s happening at the moment:

- Freeze the £85,000 registration threshold over time. Inflation is 10% this year; if we then assume 4% average inflation for the next ten years5I am also assuming politicians can resist heavy lobbying to stop the freeze. You may feel that is like assuming a spherical cow., then in real terms the threshold will be £52,000 by 2034. So a partial solution – but if the current cliff edge is a real economic problem, waiting ten years to solve it feels like an inadequate response.

What we need is a way to eliminate the dramatic “cliff-edge” effect that takes less than ten years, doesn’t just move the cliff-edge elsewhere, and is neutral in government revenue terms.

Here’s one potential solution:

Instead of a dramatic threshold, that takes VAT from zero to 20%, let’s smoothly phase it in. So, for example, at £30,000 VAT would be applied at 1% (and input tax recoverable at 1%), with the rate increasing bit-by-bit until by £140,000 VAT would fully apply at 20% (with the intention that the overall effect is revenue-neutral). The OTS proposed further investigation of such a system back in 2019, but I don’t believe it went any further.6See paragraph 1.29 here

This would once have been impractical, given that the complications it creates for business customers of a business applying (say) 7% VAT. But all VAT returns will soon be digital – so that element now feels like a relatively trivial technical problem, rather than a difficult human one.

I shouldn’t understate the challenges. One particularly difficult element is how you decide in advance what rate a business should charge. Easy(ish) for an established business with a consistent quarterly turnover. Hard for a new business, or one that’s growing or shrinking unpredictably.

You could sidestep that difficulty, but achieve an economically identical result, with a rebate system. Everyone charges 20% VAT from (say) £30,000 of turnover, but 19% of that is rebated for £30k businesses, and the rebate dropping as turnover increases, vanishing entirely at (say) £140k. If you pay the rebate quarterly in arrears then that removes the need to predict future turnover – that does, however, create a three-month cashflow problem for small businesses, and trying to solve that problem just runs into the predictability issue again. Rebate systems also can create tricky issues with cross-border supplies – how do we give foreign suppliers a rebate? And if we don’t, how can we avoid distortions and unfairness (and potentially WTO/GATS difficulties)?

And we shouldn’t minimise the political difficulties with any proposal which increases prices/reduces profit for £30k-£85k businesses. I don’t expect the immediate beneficiaries (the £85k-140k businesses) would call many demonstrations in support. So it would take a brave Government, which recognises a potential brake on growth and is willing to court unpopularity to release it.

I’d love to see this issue becoming part of the public tax debate. I can’t lie: solving it will be really hard, and require input from people with expertise that I don’t begin to have. Specifically, economists need to confirm the intuition that this is a serious problem for the UK economy, and compliance specialists (in HMRC and the private sector) need to work up a solution that doesn’t cause more problems than it fixes.

So all of this would need very serious thought, and I am absolutely not saying I have all the answers, or indeed many of the answers. I do, however, believe I have a question.

Image by DALL-E: “a colourful set of equal-sized cubic children’s wooden building blocks with the letters VAT (in order), on a wooden table, digital art”

-

1from the OTS review of VAT in 2017

-

2“up to” because many businesses will be able to recover significant input VAT. For example, if I run a restaurant with £100k of turnover, £20k of ingredient costs (plus VAT) and £30k of rent (plus VAT) then I’ll owe HMRC 20% of £100k but be able to recover 20% of £20k and 20% of £30k. My net VAT bill is therefore £20 – £4 – £6 = £10. So becoming VAT registered is actually costing me 10% of my turnover, not 20%. Contrast with e.g. if I’m a tax consultant operating out of my house with few VATable expenses – my VAT cost is then likely close to 20%

-

3The one exception here is the apparently (anecdotally) common tactic of builders asking clients to buy their supplies directly, so it doesn’t go through the builder’s books and therefore take them over the threshold. This may be tax avoidance (depending on your own perspective), but in my view it’s not improper and certainly not criminal tax evasion

-

4The chart doesn’t include the US because, whilst many States apply sales taxes with thresholds as high as $500,000, they’re conceptually very different from VATs. The rates are much lower (averaging around 6%), they don’t apply B2B, and the tax bases are relatively limited. Singapore also isn’t on the chart, as it’s not an OECD member – it has a high GST registration threshold of SGD 1m/year, but that’s much easier in a country where the tax/GDP ratio is less than half the OECD average

-

5I am also assuming politicians can resist heavy lobbying to stop the freeze. You may feel that is like assuming a spherical cow.

-

6See paragraph 1.29 here

9 responses to “Why VAT may be a brake on UK growth, and how to fix it”

Also sorry to be late this, but have only just found it (and this blog)

My thought is that the disincentive to growth – the problem described – is nothing to do with the rate of tax charged, but is a result of the cost of having to do a VAT return (and everything associated with it) – however little or much is on it.

I am just about old enough to recall two comments from when it was first introduced (50 years ago?) – one was that it essentially made millions of small businesses effectively tax collectors on behalf of Customs & Excise (as I think was); and the other that consequently required them all to keep proper accounts (for the first time)

So in effect there is a completely different problem – but what the answer is I’ve no idea. My first – and very tentative – idea is that HMRC pay something to businesses for doing (and correctly submitting) their VAT returns – I suspect that those more in the know will be able to come up with something better.

And at the same time I would greatly cut the threshold – perhaps to zero for incorporated companies or partnerships.

I am sorry for coming late to this, Dan, but I have only just managed to get round to studying in detail the paper you cite.

All of us in practice supporting smaller businesses will probably have come across examples of entities deliberately trying to keep their declared turnover below the VAT registration threshold, but I think we need to treat with caution the claims made by academics as to the extent of this issue.

The paper from Warwick appears to be based on some fundamental misunderstandings both of the VAT system and the data it is using. The two most obvious errors in the analysis are:

• the understanding of the rules for compulsory registration, and

• the treatment of the turnover figures in the CT600 (the corporation tax return)

It is implausible that the data suggests, as the paper asserts (p.7) that the forward-looking turnover test (sales of more than the threshold in the next 30 days alone) is more important than the backward-looking test. What is much more likely is that the 68% of new registrations that the paper thinks are applying the forward-looking test are carefully monitoring their historical turnover and registering, in the following financial year, as soon as they go over the threshold. The research appears to have been based on the incorrect assumption that the backward-looking test is an annual one based on an entity’s financial year, rather than one that applies at the end of every month.

The paper says (p. 9) that it takes the turnover figures from the corporation tax return form, CT600 . There is no indication given that the amounts entered in the return have been adjusted in any way, for example to gross up the net-of-VAT figure entered in the return to account for the output VAT collected be registered companies. I suspect that the use of the CT600 figures may account for much of the observed bunching below the threshold and also the apparent reduction in growth. What we have is more an artefact of a naïve research methodology than a genuine indication of potential problems with the VAT system.

To take a simple example based on the current VAT threshold of £85,000. If my company is currently unregistered and had a turnover of £84,000 for the last accounting year that is the figure I will enter on my CT600. If I grow my sales in the following year to, say, £100,000, I will register for VAT at some point in the following year and my CT600 will show the net-of-VAT figure which could be as low as £83,333 (£100k x 5/6). It will appear that my growth has stalled even though that is very far from the truth. The paper does not recognise this situation. It offers only two possible interpretations of the data (p.11) – suppression of real activity or suppression of reported purchases/sales -neither of which apply here.

My company will also be represented in the graphs to the left of the VAT threshold rather than to the right where it belongs. The CT600 data thus exaggerates the number of companies immediately to the left of the threshold while at the same time diminishing those immediately to the right. I suspect that a proper treatment of the data would eliminate much of the bunching at the threshold. Practical experience tells us that both types of suppression do exist but probably not at the scale the paper suggests.

My company will also be mis-identified as a voluntary registration (using the criteria set out on page 2 of the paper). Much of the analysis seems to be based on being able to correctly identify those businesses which have (or have not) registered voluntarily. I think we must regard any findings as unreliable.

David

thanks, David – that’s very interesting. and I’ll go through the paper again. But do you think these sorts of issues will also apply to the HMRC data on which the chart at the top of this piece is based?

I suspect it does, Dan. I have messaged the OBR to ask which HMRC figures they used when constructing their more recent graph but have yet to hear back. I think all those involved at OTS will have moved on so it may not be easy to check with them.

It’s much easier to just reduce the threshold to a very low level, so then everyone can chip in towards the essential services – which is what VAT contributes to. And the concept of having a reduced recovery rate would I think cause tremendous difficulties, because of the lack of connection often between inputs and outputs and indeed outputs may be planned but not arise, but you still get the recovery if you in the club. And someone who in your model had a 1% recovery at £30k, but grew fast. What happens then when they get to £85k and start owing full VAT – are they not entitled to that lost VAT that will be used to generate those 20% returns? How do you do this without it being really complex?

And some businesses have zero rated sales…(not that this is generally a good idea as you have discussed previously).

like many thinks in life and in VAT, sometimes what you have with all its foibles and quirks is sometimes better than tinkering – which I believe is pretty much Treasury policy after the 2012 Omni-shambles budget with it’s tinkering on pasties etc!

Great analysis Dan. But I’m not yet as convinced as you are that it’s such a serious problem . A lot of the businesses near the threshold will be lifestyle businesses where the owner never intends to grow much further in any case. Maybe some of them would grow to £100k, £120k, in the absence of VAT considerations, but not much further. Unless someone has done the research which shows otherwise ? Or do all those extra £15-35k’s add up ? Though in that case, just go the other way and push the threshold up instead.

Not all of these lifestyle businesses would exist though if it weren’t for the VAT rate. Cleaners, nannies, handyperson, person and van, etc. are all sectors where small businesses with a few employees really struggle to exist despite potential benefits of scale because they can’t compete with sole traders charging 20% less.

I am sure that you are right that the VAT threshold set at its current high level is to the detriment to the economy. It provides a strong incentive for a small business not to grow beyond that level of turnover. It also means that businesses that are registered for VAT suffer a big disadvantage versus unregistered businesses in competing for work for private customers.

Your proposed solution of a phasing in of the rate of VAT linked to turnover is ingenious and could work. However, I would advocate for the simpler solution of reducing the threshold to the OECD average. It could be done in a phased approach over a few years, e.g. give 12 months’ notice that the threshold for registration will be reduced to £70k, then by £10k each subsequent year until it reaches, say, £30k.

I would also do away with the flat rate scheme. I think that most businesses that adopt the FRS do so because their accountant has done the calculation for their particular business and worked out that they will pay less VAT under FRS than they would under the standard scheme. If you Google FRS and VAT, you will find accountancy firms giving examples of how much you might be able to save.

I don’t think that the difference between the growing and shrinking businesses curve shows that there is not significant evasion as growing businesses near the thresholds. The shrinking business will already have taken whatever detriments there might be for operating VAT, so are not going to be sufficiently concerned with a change that takes them out of VAT to themselves evade tax to dip below. And anecdotally evasion as businesses approach the threshold is a problem, that I and many other FTT judges would attest from dealing with what I suspect is the tip of the iceberg – ie those cases that HMRC discover and which the taxpayer wants to litigate especially when HMRC backdate their registration several years.

Similar anecdotage was rife in IR/HMRC at a much lower level in the past. There was a £15,000 turnover threshold under which you could compute your profits from a trade on a “3-line” basis: Turnover, total expenses and profit. Even at that level there as a big peak at £14,500 which could not have been caused by the problems that registering for VAT causes. The threshold for this was reset at the VAT threshold not so long ago and applies to landlords as well as traders.

It will be interesting to see if something similar happens for MTD for income tax, if it ever happens, now that the threshold has gone up to £50k.