5% VAT applied to tampons until January 2021 – then it was abolished. Many were hoping that the savings would go to women, in reduced tampon prices. Our analysis of ONS pricing data shows that no more than 1% of the VAT savings was passed to consumers; the rest – and very possibly all the saving – was retained by retailers.

Our report is available in PDF format here. An interactive chart demonstrating our conclusions is here. The Guardian report on our paper is here and the FT here.

A web version of the PDF report follows below:

Executive Summary

5% VAT applied to tampons and other menstrual products until January 2021. Then, following the high-profile “tampon tax” campaign, it was abolished. Many expected that the benefit of the tax saving would go to women, in the form of reduced prices.

However, an analysis of ONS data by Tax Policy Associates demonstrates that the 5% VAT saving was not passed onto women. At least 80% of the saving was retained by retailers (and very possibly all of it).

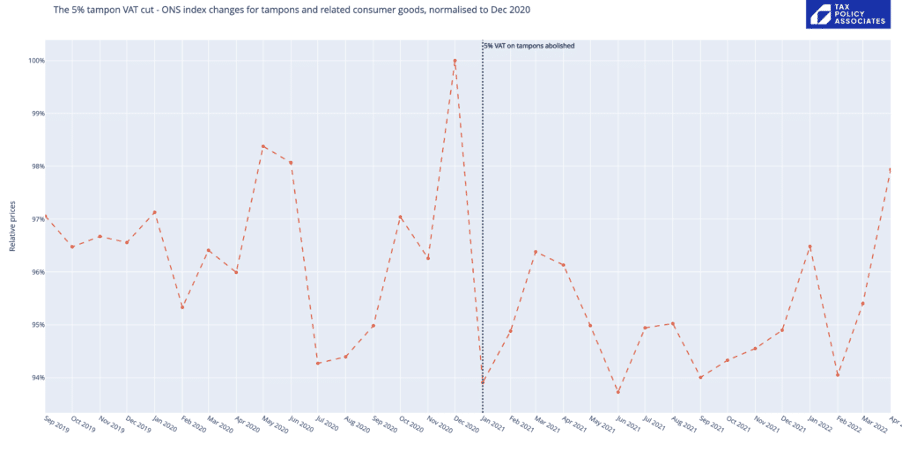

The key piece of evidence is this chart showing price changes before and after the abolition of the “tampon tax” on 1 January 2021. Ignoring the large spike in December 2020, average prices after the change are only slightly lower than before the change. For reasons explained further below, this likely reflects normal market movements rather than the passing on of the VAT saving.

Interactive charts that illustrate this in more detail are available here.

Background

Campaigners had been pushing for years for the 5% VAT on menstrual products to be scrapped[1]. EU law prevented this, but in 2016 the then-Government obtained in-principle agreement with the EU[2] that this would change. In the event, these discussions were overtaken by Brexit, and it was not until January 2021 that the tax was abolished. [3]

There will be widespread interest in who benefited from the abolition of the tampon tax – consumers or retailers. And there is also an important tax policy point. We have recently seen proposals that VAT or duties be reduced or removed from particular products or services (e.g. VAT on the tourism industry, VAT on petrol or fuel duty on petrol/diesel). However, these campaigns often assume that the benefit of the tax cuts will be passed onto consumers. The “tampon tax” provides further evidence that this will often not be the case.

Analysis

We used Office for National Statistics data to analyse tampon price changes around 1 January 2021, the date that the “tampon tax” was abolished. We were able to do this because the ONS includes tampons (but not other menstrual products) in the price quotes it samples every month to compile the consumer prices index. Since 2017, the ONS has published the full datasets for its price sampling. [4]

We set out our methodology below.

Qualitative analysis

Our methodology results in the above chart of tampon prices before and after 1 January 2021. The data is normalised to December 2020, i.e. the price on December 2020 is set at 100% for ease of reference – this facilitates easy comparisons between different products.

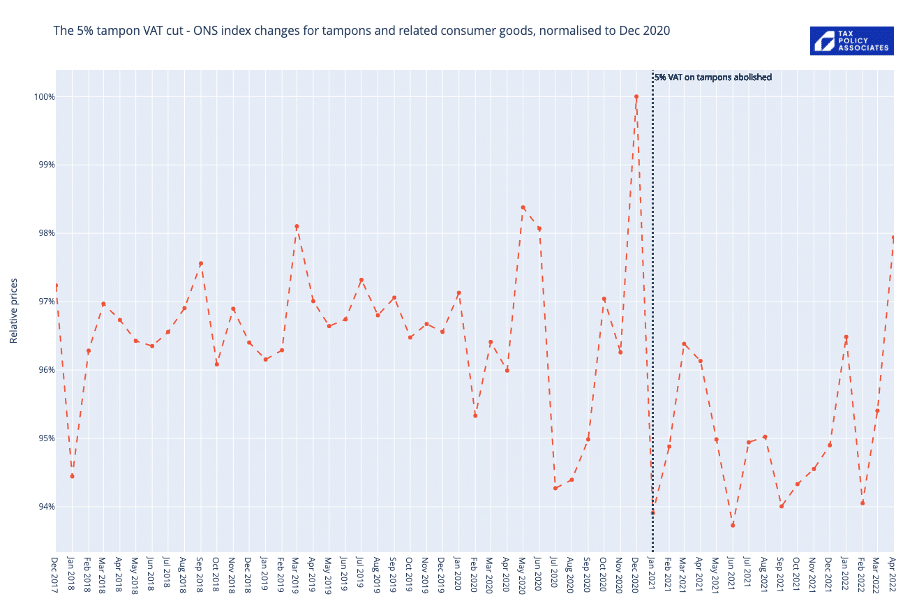

Or, over a longer period:

The charts show a 6% fall in tampon prices in January 2021 – that is largely a reversal of a 4% increase the previous month; there is then a 2.5% increase in February 2021. Overall, the average price for the period after the VAT abolition is about 1.5% less than it was beforehand.

The December 2020 price spike

It could be suggested that the 4% price rise in December 2020 was a deliberate strategy to make it look as though the 5% VAT cut was being passed to consumers the next month. However, we regard that as highly unlikely. It would require astonishing cynicism on the part of retailers. It would also suggest a degree of coordination between a large number of retailers that would be difficult to arrange in practice, as well as a flagrant breach of competition law.

As we will show below, other products also show price spikes at a variety of different times, which we expect are driven by a complex and unpredictable mixture of seasonal and situational supply/demand factors. This seems the more likely explanation. However, the fact that the December 2020 price was a “spike” means that it would be incorrect to conclude from the December and January data that tampon pricing fell by 5% when VAT was abolished.

Comparison with other products

It is insufficient to look at tampon pricing in isolation. For example, if many other consumer products were materially increasing in price in January 2021, then the absence of an increase in tampon pricing could be consistent with the benefit of the VAT abolition being passed to consumers. However, the evidence does not show this.

Our analysis includes price movements for thirteen other products that would likely be subject to similar supply and demand effects to tampons – toiletries and products made of cotton. It is important to note that none of these projects were subject to VAT changes over the period in question. Hence, if the benefit of the VAT abolition was passed on to consumers, we would expect to see a significant divergence between price changes in tampons and price changes in the other products. We do not.

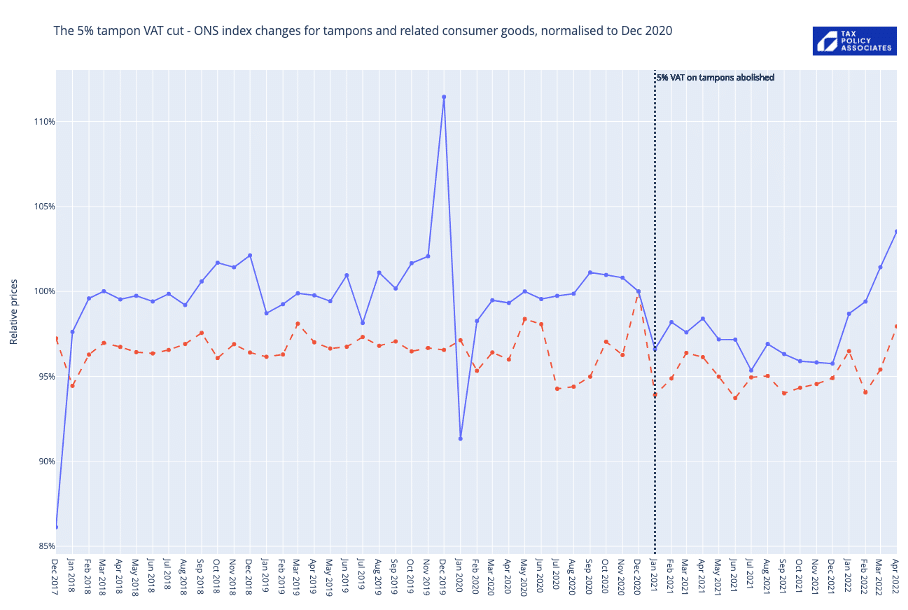

This chart compares price changes in tampons (the red dotted line) with price changes in tissues (the blue line).

The two datasets seem reasonably correlated on either side of 1 January 2021 (with the exception of a large spike in tissue pricing in December 2019, and another spike at the start of the data in December 2017). If the benefit of the tampon VAT abolition was passed onto consumers we would expect a divergence between the two datasets after 1 January, as tampon prices fell but tissue prices did not. However, we see no such effect.

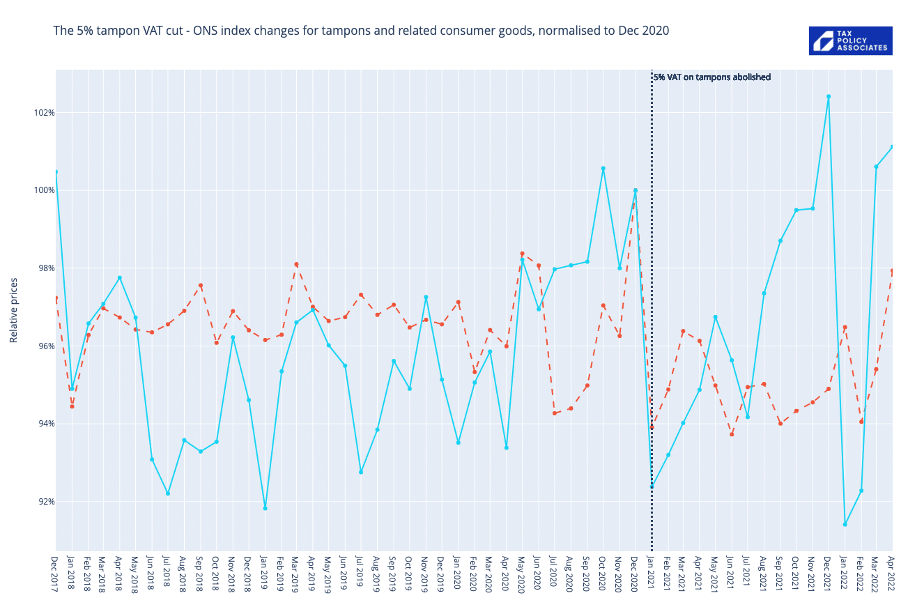

This chart compares tampon pricing (red dashed line) with t-shirts (cyan line). T-shirts are largely, but not entirely, made of cotton, and therefore are in principle subject to similar demand factors:

While t-shirt pricing seems much more volatile than tampon pricing, there is again no evidence of prices diverging after 1 January 2021.

There is an interactive version of the chart here that lets the user compare tampon price movements with the other toiletry and cotton products included in the CPI, as well as the CPI itself (which, towards the end of the period covered by the chart, increases steeply as energy costs etc start to rise). Clicking on the legend on the right-hand side will add/remove additional products.

Quantitative analysis

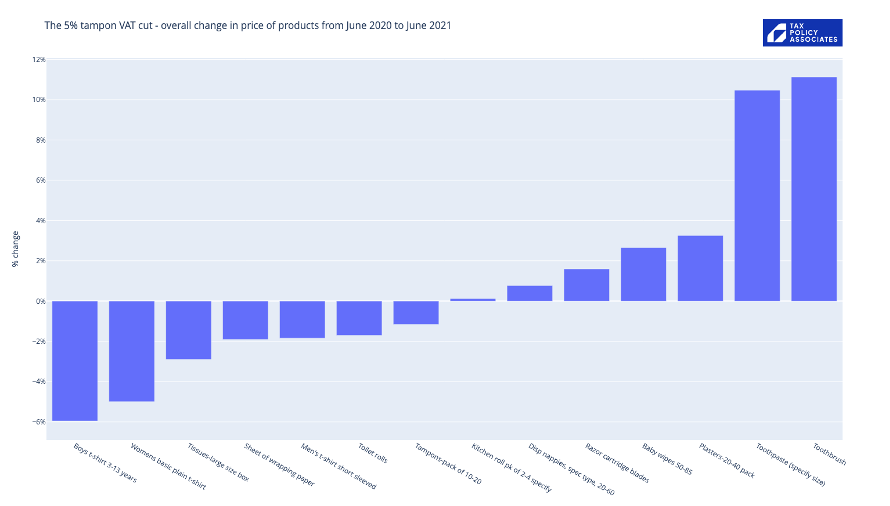

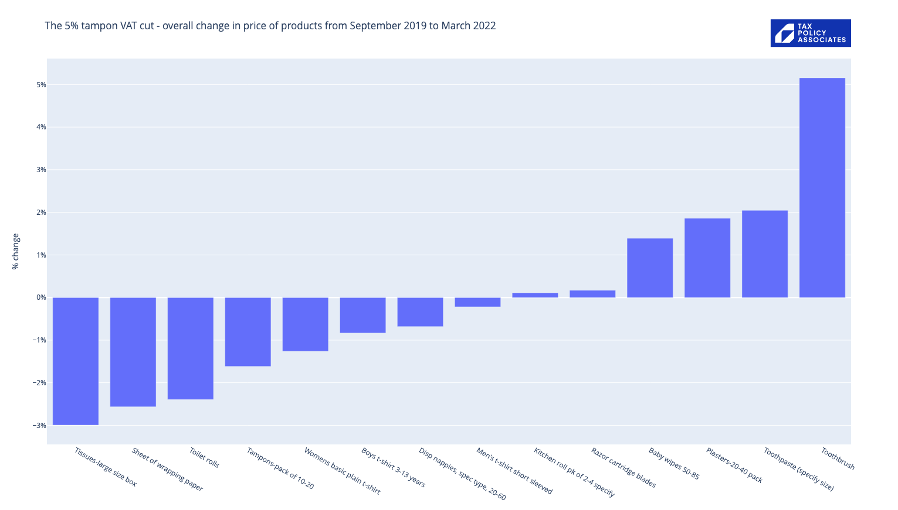

Comparing the average change in tampon prices for the six months before the abolition to the six months after confirms what we see in the above charts – the change in the price of tampons is broadly in line with other price changes we see in products where the VAT treatment did not change:

A similar picture is apparent over a longer period:

This implies that none of the VAT abolition was passed to consumers in the form of lower prices.

What if, in the interests of prudence, we ignore the other products that showed a drop in price, and look at tampon pricing in isolation? How likely is it that the apparent 1.5% drop in price is a real effect, and not just a function of the high variability of the pricing of all of these products? Our statistical analysis (see the “methodology” section on below) suggests that, at most, 1% of the price reduction was a real effect

Conclusions

Consumers did not in fact get the full benefit of the abolition of the 5% VAT “tampon tax”. At most, tampon prices were cut by around 1%, with the remaining 80% of the benefit retained by retailers. More likely, the retailers took all the benefit – amounting to £15m each year.[5]

It is open to any retailer contesting the figures in this report to publish full data showing their pricing on either side of the 1 January 2021 abolition. 1footnote Our analysis is of ONS data across retailers as a whole. It is, therefore, possible that some retailers did pass on the benefit of the VAT cut, and provided lower prices than the average figure in the data. That would, however, imply that other retailers provided higher prices. And where, as happened in at least one case, a retailer[6] announced tampon price cuts ahead of the actual abolition of the tax, that retailer should be able to demonstrate that the price cut happened, and as a result their prices remained diverged from other retailers up to (and perhaps beyond) 1 January 2021.

It is our hope that the power of the “tampon tax” campaign means that public pressure will cause retailers and suppliers, at this late stage, to pass on the full benefit of the tampon tax abolition to consumers.

Policy implications

This is an unusual case where a product is specifically included in ONS data. Prices changes are not normally so visible; nor are they normally subject to this degree of political pressure.

The public and policymakers should therefore be sceptical of those making proposals for cuts in VAT and duties, particularly if claims are made that this will benefit consumers, and/or those on low incomes (that was generally not the case for the “tampon tax” campaign, which was largely argued on a point of principle). If we want to support those who can’t afford to pay, then the answer is to put cash directly in their hands (through the tax and benefits system), or in some cases (perhaps such as this) provide free or subsidised products. We should be cautious before lowering tax rates in the hope that benevolent retailers and suppliers will pass the savings on to those who need it. The evidence from the “tampon tax” is that they won’t.

Methodology

Source of data

The Office for National Statistics compiles detailed monthly price quotes for a large variety of products, and then calculates price indices for each of those products. Since 2017, this data has been published.

To assess the change in tampon prices, we extracted the ONS data from December 2017 (When the data starts) through to April 2022,[7] and consolidated the index data for tampons and another thirteen broadly comparable products. We ended in April 2022 because after that point inflation effects start to dominate (see here).

We then wrote a short python script to analyse and chart the data. This is freely available on GitHub here. For clarity, all the price indices are normalised to 31 December 2020.

T-test

The bar charts above provide a reasonably clear indication that nothing exceptional happened to tampon pricing on the six months either side of January 2021. Whilst the average price after this date was higher than the average price before, there were greater differences in most other comparable products.

Apply statistical techniques to these datasets is not straightforward given the limited number of datapoints and very high degree of volatility. It was, however, thought appropriate to run an unequal variance one-sided t-test (using the python SciPy library) to compare the pricing datasets for the six months before 1 January 2021 with those for the subsequent six months. The null hypothesis would be that the price did not change; the alternative hypothesis was that the price was lower on and after 1 January 2021.

This resulted in the following set of p-values:

| Product | p-value (six month t-test) |

| Tissues-Large Size Box | 0.00001 |

| Women’s Basic Plain T-Shirt | 0.00627 |

| Boys T-Shirt 3-13 Years | 0.00709 |

| Sheet Of Wrapping Paper | 0.03236 |

| Men’s T-Shirt Short Sleeved | 0.09442 |

| Toilet Rolls | 0.10948 |

| Tampons | 0.14045 |

| Kitchen Roll Pk Of 2-4 Specify | 0.53249 |

| Disp Nappies Spec Type 20-60 | 0.89392 |

| Baby Wipes 50-85 | 0.95865 |

| Toothpaste (Specify Size) | 0.99270 |

| Plasters-20-40 Pack | 0.99694 |

| Razor Cartridge Blades | 0.99831 |

| Toothbrush | 0.99847 |

As expected, the p-value for tampons is not significant (> 0.05). More significant p-values were achieved for six other products, four of which were actually significant at 5%. Those products did not receive any change in VAT treatment over the period in question so, absent other unknown factors, this should be regarded as a product of the volatility of pricing decisions in a complex market environment, as well as potentially unknown supply and demand factors.

If we look at longer periods than six months then the p-value for tampons becomes more significant (because, although the average does not change, the number of datapoints increases, and significance becomes “easier” to attain). At eight months, a significant result is achieved (p-value=0.03201), although given that more significant results are (again) obtained for other products, this result should be treated with caution.

Nevertheless, if the tampon pricing results are viewed in isolation, they are compatible with the price having decreased after 1 January 2021. We can estimate the maximum likely extent of that decrease by constructing a synthetic tampon pricing sequence, identical to the actual tampon pricing sequence but with an increase of x% from 1 January 2021. If a t-test of that synthetic pricing sequence does not provide a significant p-value then that implies that the statistically significant difference between the pre-January 2021 pricing and post-January 2021 pricing is limited to a tampon price reduction of x%.

Testing different values of x, the p-value ceases to be significant with x at 1% (p-value equal to or greater than 0.0935 for any given range of months) (the precise methodology utilised can be seen in the GitHub code).

Hence, we can conclude that there is only weak evidence of any change in tampon pricing reflecting the cut in VAT, with the greatest realistic extent of any price reduction being approximately 1%.

Limitations

The analysis in this paper is subject to a number of important limitations:

- The ONS adopts a methodology that is designed to produce statistically rigorous results across consumer prices as a whole. It is not necessarily intended to provide robust figures for changes in the price of one product. Nevertheless, around 250 tampon prices[8] are sampled each month[9].

- The prices of tampons and the other consumer goods considered in this paper will be affected by numerous factors – the supply of raw materials, energy costs, and sheer random happenstance. It is therefore unsurprising that we see a large amount of month-to-month variation in prices; this makes it difficult to identify separate real trends from noise. More sophisticated statistical methods than a t-test are therefore not helpful (difference-in-difference and synthetic control methods were attempted, but did not produce meaningful results).

- The January 2021 VAT change applied to all menstrual products,[10] however ONS data only covers tampons. It is therefore possible in principle that the benefit of VAT abolition was passed to consumers of e.g. sanitary towels, although it is not obvious why that would be the case.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Arun Advani of the University of Warwick for his advice on statistical techniques, to Gemma Abbott for her advice on the background to the “tampon tax” campaign, and to Laura Coryton for her help and advice. Any errors in our analysis are the sole responsibility of Tax Policy Associates, as are the conclusions we draw from it.

And many thanks to the Office for National Statistics for publishing the data at a level of detail that facilitates this kind of analysis, and also for responding swiftly and helpfully to our queries.

[1] Technically VAT on tampons was not abolished – the rate was reduced to 0%. This is different from an exemption, because an exemption would mean that retailers can’t recover the cost of purchasing tampons from wholesalers, and would therefore probably result in higher consumer prices. However, in the interest of clarity, this report refers to “abolition”.

[2] See, e.g. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2016/mar/18/tampon-tax-scrapped-announces-osborne

[3] See the 1 January 2021 Government announcement: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tampon-tax-abolished-from-today

[4] The ONS datasets can be found here: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerpriceindicescpiandretailpricesindexrpiitemindicesandpricequotes

[5] Extrapolating from the £47m figure in the Government press release https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tampon-tax-abolished-from-today

[6] See https://www.expressandstar.com/news/uk-news/2017/07/29/tesco-beats-tampon-tax-with-5-price-cut/

[7] Most of that date is here, except the 2019 data which is here

[8] The full set of price quotes obtained in January 2021 is available here: https://www.ons.gov.uk/file?uri=/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerpriceindicescpiandretailpricesindexrpiitemindicesandpricequotes/pricequotesjanuary2021/upload-pricequotes202101.csv

[9] There are complex issues around sampling error in CPI which are outside the scope of this paper (see, for example, Smith (2021)). However, with 250 samples, the sampling error ought to be very much less than the 5% VAT reduction.

[10] The VAT term is “sanitary products” – details are in HMRC VAT Notice 701/18 – see https://www.gov.uk/guidance/vat-on-womens-sanitary-products-notice-70118

Image by DALL-E – “a pound sterling sign, £, made of tampons, digital art, on a blue background”

7 responses to “How the abolition of the “tampon tax” benefited retailers, not women”

The EU has not stood still since we left.

Article 98 of the principal VAT directive was amended in April 2022 to permit “a reduced rate lower than the minimum of 5% and an exemption with deductibility of the VAT paid at the preceding stage” for certain categories of item listed in Annex III, which includes “products used for contraception and female sanitary protection”.

To put it another way, all EU member states since April 2022 have been able avail themselves of this zero-rating treatment.

So any “Brexit dividend” from the UK’s change from January 2021 only lasted 15 months as by then we could have done it anyway.

As I recall, there has been some serious research on whether the zero rate for food in the UK (including “essentials” such as cakes, toffee apples, and candied peel for cooking, but not “luxuries” such as ice cream, unsweetened fruit bars, or roasted nuts for immediate consumption) leads to reduced food prices, compared to countries (such as France) where foods bear VAT, and the clear answer was “no”. The ridiculous antiquated excepted items, and items overriding the exceptions, are a legacy from the pre-EU purchase tax (like income tax, originally introduced as a wartime measure). But politically it will be very hard to change.

The month-by-month price data is noisy, but perhaps the statistical methods can reject either one of two possible prior assumptions: did prices of sanitary products (compared to prices of other goods) fall by 5%, or did of sanitary products (compared to prices of other goods) stay the same?

And is it possible to see what happened to prices of sanitary products when the VAT rate was reduced from 17.5% to 5% in 2001?

The data is too noisy for statistical techniques to yield much, but it seems obvious to the eyeball that, compared to other comparable goods, there was no material change in pricing over Jan 2021. The statistical analysis we did perform (the t-test) looks only at tampon pricing, and there it is clear that at most there was a 1% fall in price.

I agree with Dan, there are two major flaws with the VAT system drawn up (in about 1918). Speaking by the way as a senior VAT specialist.

1. It assumes everyone is honest when moving round the same money (elephant in the room, they are not, just the Uk VAT gap is £9bn a year)

2. There are different rates. This just creates complexity and avoidance and also reduces the taxes needed to pay for things.

On this latter point, for decades the EU discouraged zero rates and even reduced rates but has now done a 180 and changed policy and look at what has happened?

The politicians in their country are as good as ours and so telling people that they are being nice by reducing VAT on ‘essentials’ sounds great, you are Mr or Mrs Popular.

But the thing is this massively reduces the tax cash you need to pay for things and also is mostly absorbed as Dan has shown by retailers and taken as profit.

When the chickens come home to roost down the line and tax revenues are decimated and so public spending is needed to be reduced, the politicians are unlikely to be in power or by then there would be a myriad of other excuses they can blame, wars etc.

But the bottom line is taxes are needed to pay for things we all need and it’s far better to help the poorer in society by grants etc than tax cuts.

I don’t need my gas bill to be less through VAT and so what’s the sense in giving me a VAT reduction?

What do you think the most attractive idea is to a politician. Hand out benefits or cut taxes?

The EU did a study the other year that demonstrated removing the reliefs would allow a reduction in the headline rate of about 7%.

They ignored this report and I believe they will pay the price for this.

In the UK we have even more zero or reduced rates so what could our headline rate be?

I agree with Dan, there are two major flaws with the VAT system drawn up (in about 1918). Speaking by the way as a senior VAT specialist.

1. It assumes everyone is honest when moving round the same money (elephant in the room, they are not, just the Uk VAT gap is £9bn a year)

2. There are different rates. This just creates complexity and avoidance and also reduces the taxes needed to pay for things.

On this latter point, for decades the EU discouraged zero rates and even reduced rates but has now done a 180 and changed policy and look at what has happened?

The politicians in their country are as good as ours and so telling people that they are being nice by reducing VAT on ‘essentials’ sounds great, you are Mr or Mrs Popular.

But the thing is this massively reduces the tax cash you need to pay for things and also is mostly absorbed as Dan has shown by retailers and taken as profit.

When the chickens come home to roost down the line and tax revenues are decimated and so public spending is needed to be reduced, the politicians are unlikely to be in power or by then there would be a myriad of other excuses they can blame, wars etc.

But the bottom line is taxes are needed to pay for things we all need and it’s far better to help the poorer in society by grants etc than tax cuts.

I don’t need my gas bill to be less through VAT and so what’s the sense in giving me a VAT reduction?

What do you think the most attractive idea is to a politician. Hand out benefits or cut taxes?

The EU did a study the other year that demonstrated removing the reliefs would allow a reduction in the headline rate of about 7%.

They ignored this report and I believe they will pay the price for this in a huge reduction in tax revenues.

In the UK we have even more zero or reduced rates so what could our headline rate be if we simplified things?

Great to be able to comment on this. I have campaigned for over 40 years to rid our society of ridiculous taxation on essential items, toilet paper and sanitary products. There is a system that will make taxation fair for all and prevent avoidance. Many government departments are aware of this. As yet they have been silent. I won’t give up.

Just been looking at data regarding views and time spent on the website http://simplifyourtax.com there has been more time spent by Chinese people in the city of Guangzhou than in London. I looked it up. that city is the Financial hub of China. Interestingly

I don’t agree at all. The best VAT systems apply at the same rate to all products. Defining “essential” is a one-way track to uncertainty, distortion and avoidance.