We all pay stamp duty when we buy a house. But there’s a well-known trick: have your house owned by a company – a special purpose company that does absolutely nothing else (often called “enveloping”). Then, when you come to sell, you sell the shares in the company, and the buyer1 since it’s the buyer making the stamp duty saving, why does the seller go to the trouble of enveloping the property? Because in practice, stamp duty is economically shared between the buyer and the seller, and by arranging a stamp duty-free sale, you expect that you are increasing your future sale proceeds. pays no stamp duty.2If it was a UK company, there would be 0.5% UK stamp duty/stamp duty reserve tax. So all envelopes are in practice non-UK companies. Do people really go to this trouble just to save 0.5%? Yes – helped by the fact that it is often cheaper to maintain an offshore company than a UK company.

This had been going on forever, but became widely publicised in the early 2010s. In a sane world, the “loophole”3Scare quotes because I have zero interest in arguing whether or not it is really a loophole would’ve been closed by simply applying stamp duty to the sale of the shares. But for obscure reasons,4in large part EU law complications around the Capital Duties Directive the loophole was left open, but anyone exploiting it and buying residential real estate held by a company was stung with an annual tax – the “annual tax on enveloped dwellings” introduced in 2013 – ATED.

The idea was that the prospect of paying an annual tax would put people off enveloping altogether – ATED wouldn’t raise much money, but would increase stamp duty revenues. That didn’t quite happen – and ATED, the tax that nobody was supposed to pay, ended up raising over £100m each year, with around 5,000 residential properties still held in envelopes (including about 100 properties worth more than £20m).

Why are people stubbornly keeping their homes enveloped, despite ATED?

Sometimes to hide the identity of owners (whether because of security concerns or more malign reasons) – although this will now be harder to do.

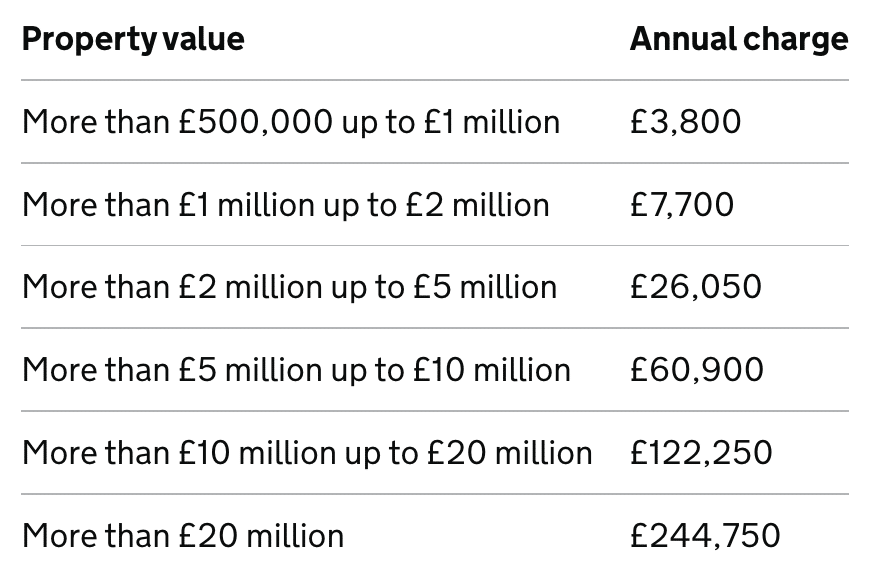

Sometimes simply because ATED is way too small to undo the stamp duty saving from enveloping. The tax applies in bands like this:

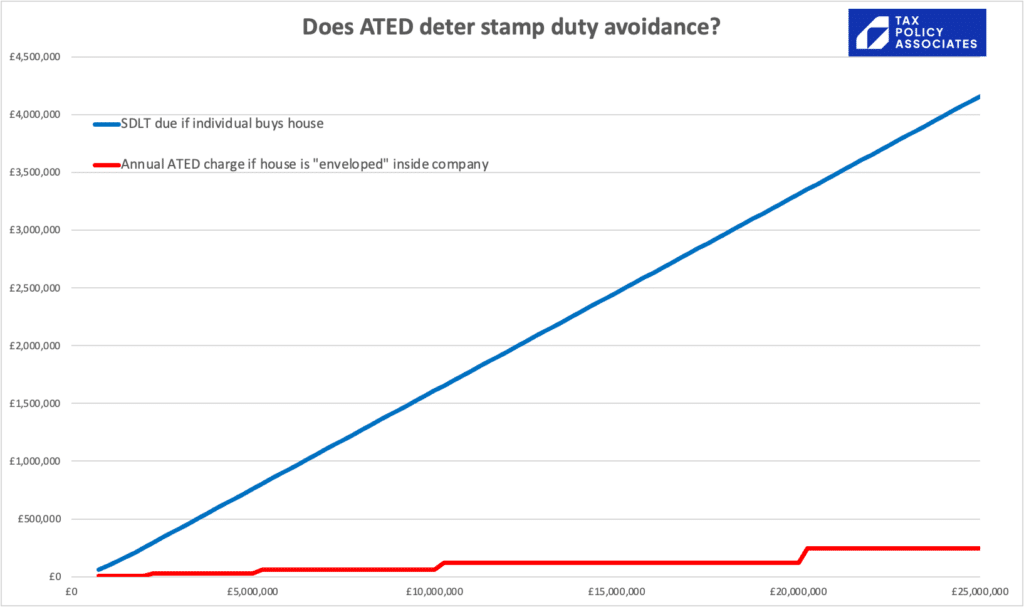

This means that the gap between stamp duty and ATED is fairly dramatic, particularly at the high end.

In other words:

- Stamp duty on a £1 million house is £91,250.5This, and the other figures here, all assume that the buyer is a non-resident who already owns property ATED at that level is only £3,800. So you could happily pay the annual tax for 24 years before your total ATED bill exceeds the stamp duty you’d have paid if the property wasn’t enveloped.6This ignores set-up and maintenance costs; but it also ignores the time value of money, so I don’t think it’s an unrepresentative way to look at things. Let’s call 24 years the “ATED break-even point”.

- Or more dramatically, stamp duty on a £25m house is over £4m. ATED is £244,750/year. So the ATED break-even point here is 17 years – i.e. you’d have to pay ATED for 17 years before the cost exceeded the stamp duty saving.

- And ATED caps out at £244,750. So once we get into truly silly money, the benefit becomes stark: stamp duty on a £100m house is a cool £17m – the ATED break-even point is 69 years.

So ATED is too low to do the job it was designed to do. The enveloping “loophole” is still worthwhile, and the more expensive the property, the more worthwhile it is.

The sensible solution is to close the loophole properly, and make stamp duty apply on the sale of companies holding residential real estate (just as I think we should for companies purchasing commercial real estate). But if we don’t want to do that (or want a stopgap while we finalise how we’re going to properly sort things out), let’s just increase ATED.

ATED currently raises £111 million, and the average ATED break-even point is about 20 years. So if we triple the rate, we can expect to raise around £200m – much of which would be in increased stamp duty revenues, as people “de-envelope”.7Ordinarily one worries that greatly increasing a tax will take it past the “revenue maximising” point, and actually reduce revenues (as well as do economic harm). Here we can be reasonably relaxed, because the unusual nature of ATED means that the revenue-maximising point will be where the level of ATED exactly equals the benefit that people receive from enveloping. This can’t realistically be calculated, because it will vary dependent on personal circumstances. But the important thing is that people always have an escape route – they can “de-envelope” and suffer stamp duty on their sales instead of ATED – so there shouldn’t be a risk of damaging revenues or the housing market by setting ATED too high (even if the ATED rate was set at $100bn, we would remain at (and not past) the revenue-maximising rate) That would reduce the average ATED break-even point to around 6 years, which seems a more realistic timeframe for ownership of high-value real estate. We’re not quite done: increasing ATED at each of the existing bands doesn’t solve the problem of ATED “capping-out” for very high-value properties – here, the obvious solution is for ATED to continue to apply at each additional £5m of value.8Of course one could instead have a percentage charge, but that then creates a need for precise valuation, which is probably just justified given the small scale of this tax

This seems a simple, fair and straightforward-to-implement way to raise £200m. How could any Chancellor resist such a proposition?

Photo of One Hyde Park by Rob Deutscher Follow, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Why pick a picture of One Hyde Park? No particular reason.

-

1since it’s the buyer making the stamp duty saving, why does the seller go to the trouble of enveloping the property? Because in practice, stamp duty is economically shared between the buyer and the seller, and by arranging a stamp duty-free sale, you expect that you are increasing your future sale proceeds.

-

2If it was a UK company, there would be 0.5% UK stamp duty/stamp duty reserve tax. So all envelopes are in practice non-UK companies. Do people really go to this trouble just to save 0.5%? Yes – helped by the fact that it is often cheaper to maintain an offshore company than a UK company.

-

3Scare quotes because I have zero interest in arguing whether or not it is really a loophole

-

4in large part EU law complications around the Capital Duties Directive

-

5This, and the other figures here, all assume that the buyer is a non-resident who already owns property

-

6This ignores set-up and maintenance costs; but it also ignores the time value of money, so I don’t think it’s an unrepresentative way to look at things.

-

7Ordinarily one worries that greatly increasing a tax will take it past the “revenue maximising” point, and actually reduce revenues (as well as do economic harm). Here we can be reasonably relaxed, because the unusual nature of ATED means that the revenue-maximising point will be where the level of ATED exactly equals the benefit that people receive from enveloping. This can’t realistically be calculated, because it will vary dependent on personal circumstances. But the important thing is that people always have an escape route – they can “de-envelope” and suffer stamp duty on their sales instead of ATED – so there shouldn’t be a risk of damaging revenues or the housing market by setting ATED too high (even if the ATED rate was set at $100bn, we would remain at (and not past) the revenue-maximising rate)

-

8Of course one could instead have a percentage charge, but that then creates a need for precise valuation, which is probably just justified given the small scale of this tax

6 responses to “ATED – the obscure tax that nobody was supposed to pay (and why we should raise £200m of tax by increasing it)”

This envelope structure became very popular in South Africa in the early 2000s. The law was promptly changed to ensure that “Transfer Duty” (equivalent to SDLT) is payable when shares in a residential property-owning company (one whose assets exceed 50% residential property) are sold.

Problem solved, without having to create an alternative such as ATED.

Hi Dan- interesting article. We have a ‘landholder duty’ in all Australian states and territories to catch transactions in shares, rather than the underlying asset. It can in certain cases exceed the equivalent value of stamp duty (particularly for foreign headquartered property developers). The debate in my home state, NSW, is whether the stamp duty on residential real estate is changed to an annual land tax, which as your other correspondents have noted is much more economically efficient. It is hard for the govt to transition away from the ‘sugar hit’ of revenue of a purchase price based tax in a bouyant market, than a smoother annualised land tax. A very political discussion!

Thanks for a fascinating insight into a world I previously knew very little about.

I have to confess some scepticism about the concept of stamp duty land tax at all. Since it is a tax on transactions (a) it discourages liquidity in the housing market and makes it more difficult for people to move house in order to maximise their economic potential and (b) it is unfair, because buyers will pay the same amount irrespective of the capital appreciation they have made in the property market.

Wouldn’t it instead be better to move everyone onto an equivalent of ATED, but set at a higher rate and without a cap?

Indeed. Scrap SDLT and turn council tax into a proper tax on real estate value!

Hi Dan. Another really interesting article – thanks! As you note in the piece, the economic burden of SDLT is shared between both sides to the sale, hence the incentive for the seller to envelope in the first place. Presumably any purchaser looking to subsequently ‘de-envelope’ would be subject to SDLT in full at that point (i.e., as a sale by the company and purchase by the individual), so the property would essentially become ‘trapped’ in the envelope – or is there any further complexity here that would allow the individual to take the property out of the envelope?

that’s a great point – one might imagine some form of partial SDLT relief on de-enveloping transactions that are (for example) more than six years after the purchase of the property.