The two biggest tax-cutting Conservative Chancellors in British history both increased capital gains tax – and for good reasons. Jeremy Hunt should follow them, and raise £8bn.

Here’s the current situation: someone earning £50k pays income tax at a marginal rate of 40%; someone earning £150k pays a marginal rate of 45%. But the same person making a capital gain pays nothing on the first £12,300 of gain, and only 20% on the rest. This is a problem for several reasons:

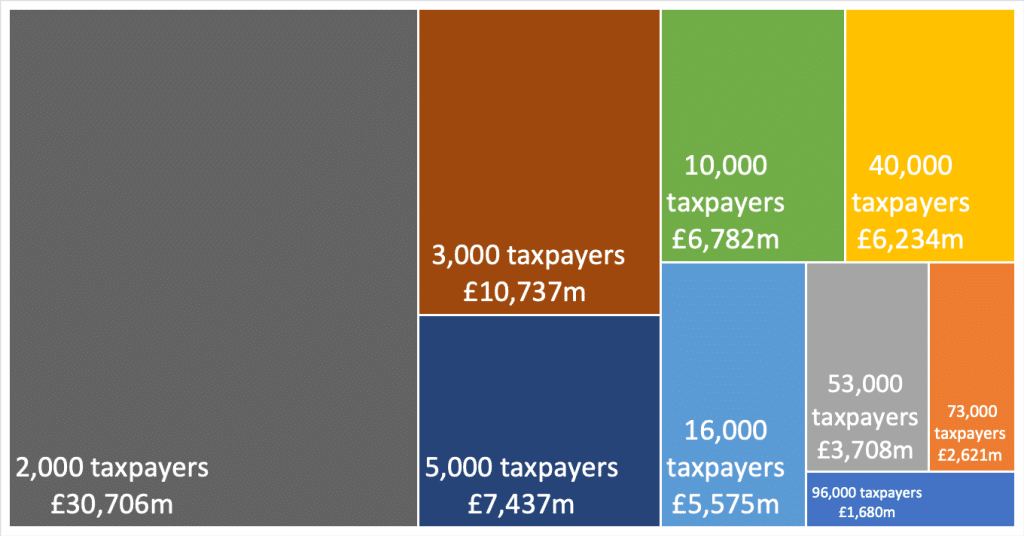

- It’s inequitable that a type of income received mainly by the wealthy is taxed less than other types of income (and particularly employment income). “Mainly” understates the case – HMRC statistics show that over half of all taxable gains are received by only 5,000 people:

- The difference between income tax and capital gains tax rates is so great that it creates a powerful incentive to shift income into capital. This can be done on a small level by an individual investor – for example, if you hold shares in a company or mutual fund about to pay a large dividend, then that dividend would be taxed at a top marginal rate of 39.35%. If instead, you sell the shares after the dividend is declared (but before it is paid) then you’re receiving the value of the dividend (embedded in the share price), but only paying 20% capital gains tax. It can be done on a much larger scale by a large investor, or indeed the owner of a sizeable private company.

- On a larger scale, a good chunk of the private funds industry gives its executives “carried interest” in its funds, which makes up the majority of their remuneration. This is usually subject to capital gains tax at 28% (a higher rate than usual, but still considerably less than the 39.35% dividend rate). That is inequitable. It also creates a distortion where the precise nature of an asset management business can have a dramatic effect on the tax paid by its executives1for example Anthony managing “managed accounts” for several large clients can’t have carried interest; Amelia managing a private fund for several large clients can. That’s an undesirable and inefficient distortion.

- And finally, there’s a £12,570 personal allowance for income tax – anything below that isn’t taxed. Fair enough. But then there’s another completely separate £12,300 allowance for capital gains. Shouldn’t there be just one allowance for everything? (Perhaps with a small de minimis, say £1,000, to remove the need for filing for small gains.) Otherwise it’s just a £2.5k giveaway to investors, and one which is widely gamed.

To my mind, the case for change is irresistible.

How did we get into this mess?

Today’s CGT problems are nothing compared to how things were before 1962, when capital gains were completely untaxed. So when you see 90%+ top rates of income tax in the 1950s, you’re safe to assume that the properly wealthy took most of their returns as capital gain, and paid no tax at all. The halcyon days of progressive taxation it was not.2To return to a recent theme: never, ever, look at tax rates in isolation – the question is *what* the rates apply to, and what they *don’t*.

Then in 1962 the second most spectacularly tax-cutting Chancellor in British history, Anthony Barber, introduced (when he was Financial Secretary to the Treasury3I got this muddled in my first draft, and said Barber was Chancellor in 1962, which he wasn’t until 1970) a “speculative gains tax” that taxed some short-term capital gains as income (countering some of the most obvious avoidance schemes that were around at the time). Three years later, an actual capital gains tax was introduced, at a flat rate of 30%4There is a nice summary of the history from HMRC here. Again much less than the rate of tax on normal income – I’m not clear why.

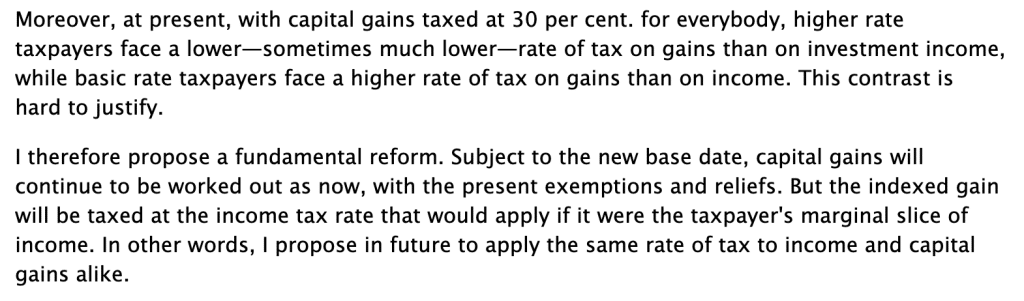

The rate stayed at 30% for 20 years, with an “indexation allowance” introduced in 1982 so that inflationary gains wouldn’t be taxed. And then the absolutely most spectacularly tax-cutting Chancellor in British history, Nigel Lawson, in the absolute most tax cutting Budget in British history, increased the rate in 1988, so it applied at whatever the taxpayer’s marginal rate was. His explanation couldn’t have been clearer:

There it stayed throughout the Blair premiership.5I’m skipping over the taper, entrepreneur’s relief etc Then one of Gordon Brown’s big mistakes – he and Alistair Darling cut the rate to 18% in 2008. George Osborne pushed it back up to 28% in his first Budget in 2010; then cut the rate to 20% (in most cases) in 2016.

This leaves us today with the problem that Lawson thought he’d solved: a capital gains tax rate that’s often much lower than the income tax rate.

What’s the answer?

In short:

- Go back to the Lawson solution, with capital gains charged at the same marginal rate as income.6The trust rate would also have to be increased.

- One exception: just as dividends are taxed at a somewhat lower rate than other income (to reflect the fact they’re paid out of a company’s post-tax profits), so capital gains in shares should be taxed at a somewhat lower rate. The obvious answer is to simply apply the relevant dividend rate.7If you don’t buy the logical argument for this, then accept the pragmatic one: if the CGT rate is higher than the dividend income tax rate, people will shift from gains into dividends. That’s precisely what happened in the post-Lawson era, with people using scrip dividends for this purpose.

- Merge the income tax and CGT personal allowances. Once the allowance is used, all capital gains should be taxable (with say a £1,000 de minimis to prevent taxpayers and HMRC having the hassle of dealing with small gains).

- If we keep Business Asset Disposal Relief then there should be little/no impact on small businesses (which is where much of the debate has been around changing CGT rates, even though CGT is mostly paid elsewhere).

- Care also needs to be taken to introduce any increase in CGT rates very quickly, ideally overnight. Otherwise, people will accelerate gains to beat the rate increase. If an incoming Labour Government plans to increase the rate then it may be wise to pre-announce it ahead of a Budget, and very soon after the election, with the new rate applying retrospectively from the date of the announcement.

None of this is very controversial in tax policy circles. Rishi Sunak asked the Office of Tax Simplification to look into problems with CGT, and equalising rates and reducing the allowance were their key recommendations. Sadly, Rishi shelved it.

There is a debate to be had as to whether, if we’re returning to the higher rates of the 80s and 90s, we should return to having an indexation allowance so that inflationary gains aren’t taxed. The argument for: it’s unfair to tax a gain that isn’t real. The argument against: we tax inflationary elements of income returns (e.g. interest on a loan, bond or bank account is fully taxed). On balance, I would probably tend to providing an inflation allowance (or, alternatively, follow the Mirrlees Review recommendation of giving an allowance equal to the risk-free return on government bonds), but I do not have a strong view.8There’s a good discussion of this in Arun Advani’s paper here.

Would increasing the rate of CGT adversely affect business investment?

There is no evidence for that. IFS research has found that the current low CGT rates save plenty of tax for investors, but don’t increase investment.

How much would it raise?

In 2020-21, CGT raised a record £14.3bn. I estimate an additional £7bn would have been raised that year if CGT rates had been equalised with income tax and dividend rates9Much of the revenue would be income tax, as people cease bothering to convert income to gains. That’s on the basis of a simple static analysis applied to HMRC data on how much gain is attributable to the various different asset types. It’s quite a lot less than some other estimates out there, very possibly because I am equalising at the dividend tax rate, not the income tax rate.

HMRC estimated that in 2020-21 the £12,300 annual allowance cost £900m.

So overall we are looking at approximately £8bn of revenues. Dynamic effects will reduce this, but I don’t expect by much provided sensible steps are taken to protect the base.

-

1for example Anthony managing “managed accounts” for several large clients can’t have carried interest; Amelia managing a private fund for several large clients can. That’s an undesirable and inefficient distortion.

-

2To return to a recent theme: never, ever, look at tax rates in isolation – the question is *what* the rates apply to, and what they *don’t*.

-

3I got this muddled in my first draft, and said Barber was Chancellor in 1962, which he wasn’t until 1970

-

4There is a nice summary of the history from HMRC here

-

5I’m skipping over the taper, entrepreneur’s relief etc

-

6The trust rate would also have to be increased.

-

7If you don’t buy the logical argument for this, then accept the pragmatic one: if the CGT rate is higher than the dividend income tax rate, people will shift from gains into dividends. That’s precisely what happened in the post-Lawson era, with people using scrip dividends for this purpose.

-

8There’s a good discussion of this in Arun Advani’s paper here.

-

9Much of the revenue would be income tax, as people cease bothering to convert income to gains

14 responses to “How to raise £8bn by increasing capital gains tax”

You failed to consider the “moving to a tax haven” – e.g. New Zealand / Belgium / somewhere hot – for 5 years issue.

If you have a £1m+ potential tax bill you effectively get paid £200k per year (after tax – so close to £400k before) to move somewhere hot and sunny and do nothing – vs live in the UK and work hard /take risks…

As the rate goes up the number of people considering this option increases.

What’s your evidence for this claim? Looking at data on CGT collected, it does not appear to be true.

https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=REVGBR

Taper relief was introduced in 1998, following which there was an immediate, significant and sustained increase in CGT collected, even with a much lower tax rate.

You might argue that people started shifting income into gains after this – who knows – but it’s difficult to find any support for what you’re saying in the data. I suspect many people took the view that if the Govt was allowing them to sell their companies at 10% tax, great, I’ll sell.

The common sense answer to aligning CGT with income tax remains as set out above. People will not sell assets if to do so would significantly worsen their financial position.

I’ll post some data on this soon.

If you have data showing a material decrease in CGT collected after Gordon Brown introduced taper relief, then fair enough. You might reasonably assume a corresponding increase if you hike the CGT rate. I still don’t think most in the position above would sell (and there are plenty of business owners in this position). They could just hold until death, keep receiving an income yield on the untaxed/ gross value, and get BPR with a CGT base cost uplift, assuming you don’t shut that down as well…

I doubt the £8bn figure is accurate and I really don’t think this is a good idea at all. One obvious consequence is that people would be less inclined to sell their businesses (I don’t mean small businesses – the £1m BADR allowance won’t do much for owners of medium-sized or large businesses). I am going on memory here but I think I’m right in saying that when CGT was at 40%, we also had business asset taper relief, which was uncapped. Just as a question of maths – why would anyone sell an income producing asset only to lose almost half its value in tax (assuming no/ low base cost)? You can retain the asset and get an income yield on the gross/ pre-tax value, whereas if you sell you will be investing the net and receiving a much lower return. The same logic would apply to other assets, in addition to businesses.

I don’t agree with either point.

Taper relief was introduced by Gordon Brown – we operated with 40% tax plus indexation for many years, and I don’t see why we couldn’t do that again.

If you retain the asset you receive an income yield that’s fully subject to tax. So it’s perfectly rational for selling the asset to be taxed at the same rate.

Pre Gordon Brown is before my time!

You say it is “rational” to tax the capital gain at the same rate as the income stream. Whether or not this is right, it is surely going to act as a disincentive to sell assets.

Suppose I founded a company which is now worth £20m and produces £2m/ year in dividends. I am now 45 and am considering selling and doing something else. If I did sell, I would not spend the whole £20m immediately – I would need to invest some for the long term.

At the moment I am receiving a 10% yield on the gross value of the asset.

If I sell and am taxed at 45%, I will lose almost half of the asset value and will only receive an income yield on £11m of assets rather than £20m. It may be a stretch but if even if I can get a 10% return per year, that is clearly only £1.1m. So selling does not make sense. I will just hold on to the asset. Your £8bn figure really needs to factor this in and it may in fact either reduce the £8bn, or even turn it into a negative figure. Query also what the wider economic effects of companies/ assets remaining in the same ownership long term would be.

Just to add – if on the other hand you offer me a 20% CGT rate, you are giving me an incentive to sell the asset and generate money for the Exchequer (or at least not disincentivising me to the same extent that your proposed alignment would). Clearly, a capital asset is not like salary. I can’t really just stop receiving a salary, but I can and will refuse to sell an asset if you make it strongly against my interests to sell it.

That’s a testable hypothesis – look at what happened when the rate was cut from 40%. Was there a significant and sustained increase in disposals? There was not.

Indexation was introduced in 1982 because of the high rate of inflation then. Without it, Nigel Lawson could not have unified the rates of income tax and CGT. As inflation waned and time wore on, it became harder and harder to make the indexation calculations, especially for non-professional investors and where assets had been added to over time (e.g. upgrades to second homes). Abolition of indexation and the adoption of a lower rate of tax on capital gains were two sides of a single coin, a rough-and-ready response to practical difficulties.

I don’t agree with that – most of the time, indexation isn’t that complicated, and the complications don’t justify the inequity and distortions that result from taxing capital gains at half the rate of income.

I’m not saying Nigel Lawson’s approach wasn’t right: intellectually it is admirable. What I was trying to do was to provide a perspective of what I recall as having been the views at the time of commentators and non-professional investors who faced CGT bills. You have also (not unreasonably) failed to indicate the complexity of the CGT calculations once indexation had been introduced (it’s simple in theory; more difficult once you get into the rules on partial disposals and further purchases). For non-financial assets there were also difficulties in obtaining a retrospective valuation at the baseline date. The whole thing became a gravy train for professional advisers. Some of those issues would be addressed today by tax return software; others (such as retrospective valuations at the baseline date) would remain.

Kwasi who?

I agree completely with your analysis and proposal. Even if it does also mean agreeing with Nigel Lawson.