It’s often said there’s been a race to the bottom in corporate tax, with tax competition resulting in corporations paying less and less over the last few decades. The most recent claim was by the IPPR, which I commented on here.

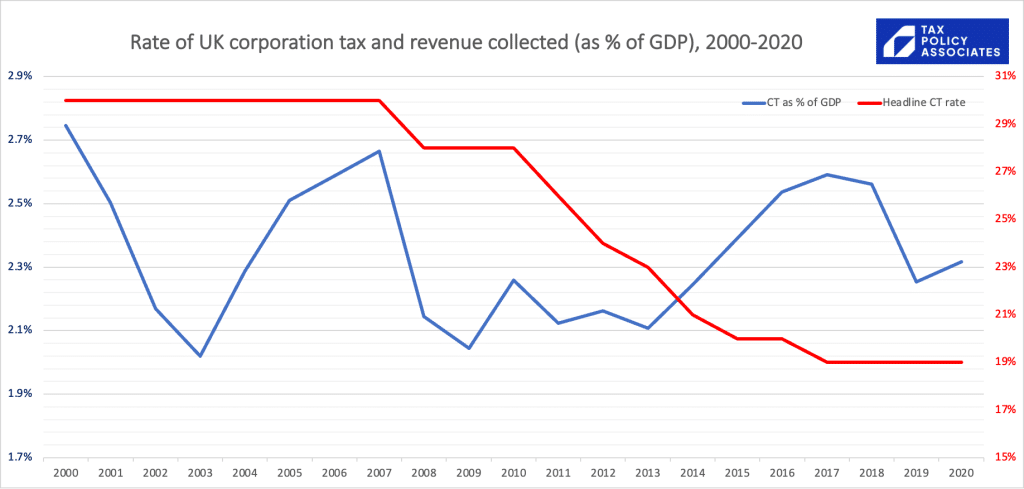

These claims are wrong, at least when it comes to the UK: the UK corporate tax rate plummeted over the last 20 years, but the actual tax collected, as a percentage of GDP, stayed broadly the same. See the chart above or the OBR piece here.

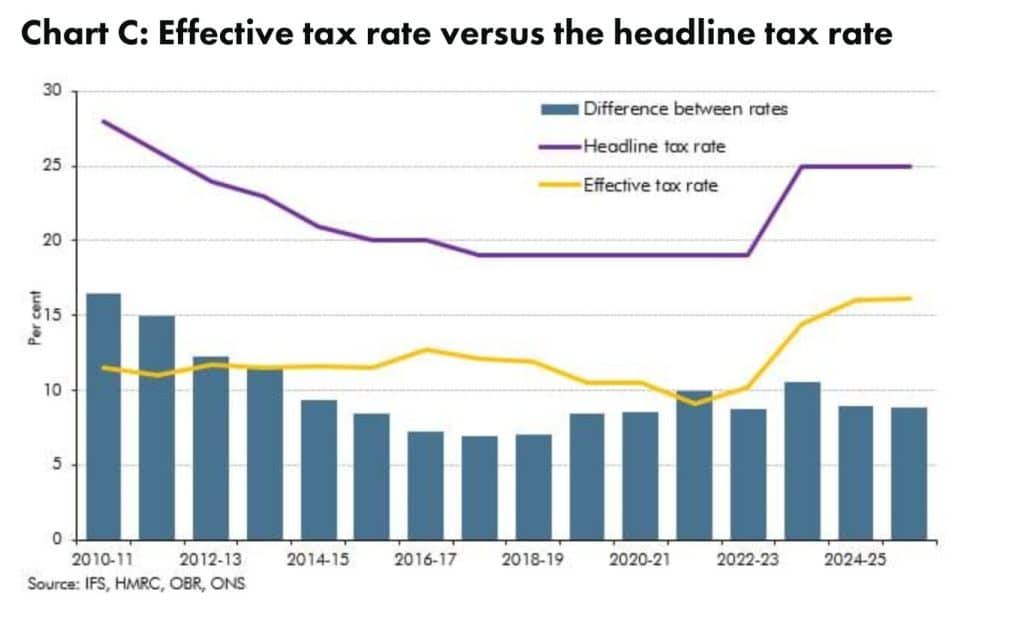

Why? Because a company’s corporate tax liability is the tax rate multiplied by its taxable profit. The UK definition of “taxable profit” – often termed the “tax base” – has expanded over the same period that the rate fell. Either by accident or design, the two effects broadly countered each other.1With some noise from “incorporation” – sole traders establishing companies to save tax, which tends to reduce income tax/national insurance and boost corporation tax – but not enough to make a difference to this analysis. This means that the average effective tax rate (i.e. tax paid divided by profits) is largely unchanged:2This comes from the excellent OBR piece. Well worth a read

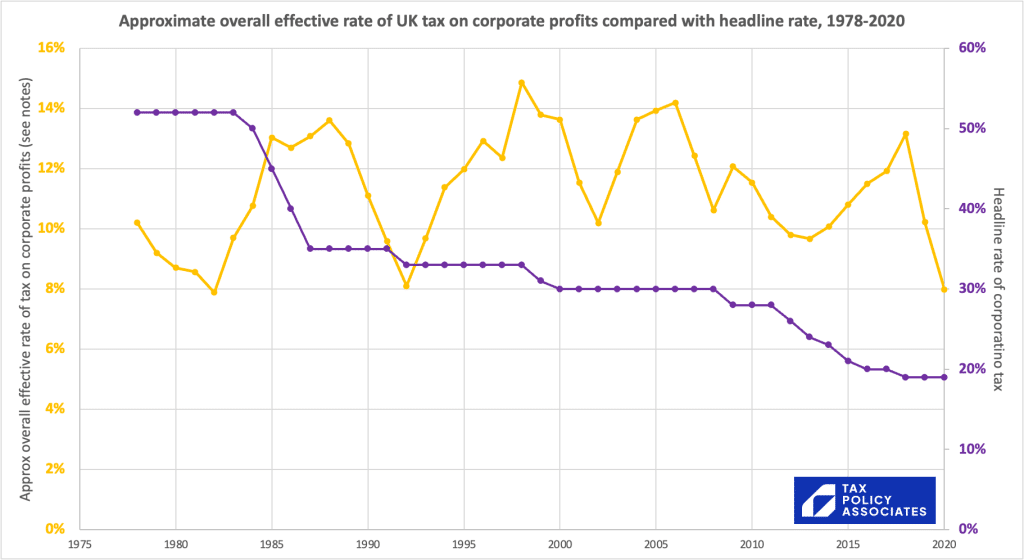

Unfortunately, the ONS doesn’t publish that chart going back further than 2010 – but we can calculate a reasonable proxy for effective tax rate using the ONS data for corporate gross operating surplus. That results in this chart, which needs to be read with many many caveats,3The two big ones: (1) GOS is not the same as accounting profit, and in particular excludes depreciation (so the chart understates ETR), (2) the tax stats are for cash collected by HMRC in a tax year, which used to lag profits by around a year, and now mainly doesn’t – neither factor should affect the overall trend, but both will create/mask considerable noise. With some work they could be corrected. but nevertheless is a good indication that the long-term trend is indeed that the headline rate (purple) plummets, but the effective tax rate (yellow) does nothing much at all.

So the stories people tell of [brave tax-cutting Chancellors][evil tax-cutting Tories] are all wrong, and are because people are looking at the (mostly irrelevant) purple line. The yellow line – reflecting the tax actually paid – tells us that corporate tax wasn’t cut at all – it just changed in lots of very complicated and opaque ways. Great.

What about other countries?

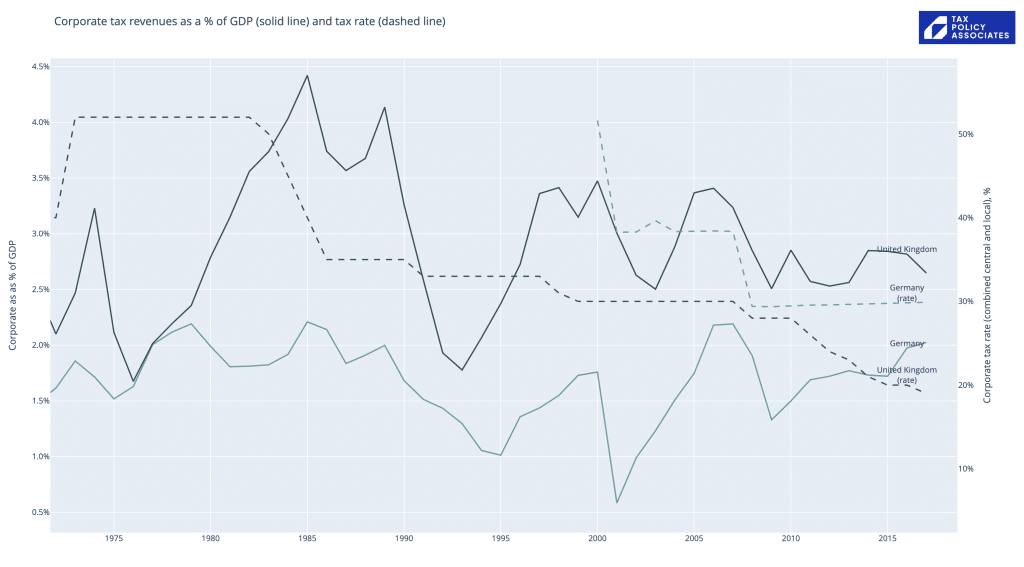

I’ve quickly pulled together some data from the OECD’s fantastic corporate tax database, and have made an interactive chart that lets us compare corporate tax rates and revenue across the OECD. Click this image:

The OECD sadly only has tax rate data going back to 2000 – I added the earlier UK tax rate data myself. But you can zoom and focus on 2000-2020, then click on the right hand side to select/deselect individual countries.4If anyone can point me towards pre-2000 tax rate data I’d be most obliged.

The code and underlying spreadsheet is here.5If you have feedback on the quality of my incredibly amateurish coding then please do add comments on our official code feedback page here.

Unfortunately, I can’t find useful international gross operating surplus data, so can’t compare effective tax rates across the OECD.6The OECD data only goes back to 2008 If anyone can find that data, please let me know.

So what?

I can play with the interactive chart all day but – fun as it is – it’s just cherry-picking.7Just promise me you won’t look at the US chart, because pass-through taxation (company profits taxed in the hands of owners/shareholders) means US corporate tax statistics can’t easily be compared with other countries’.

The question we really want to answer is: is there evidence across the OECD that falling rates drove falling revenues over the period 2000-2018?

I’ll post more on this soon.

-

1With some noise from “incorporation” – sole traders establishing companies to save tax, which tends to reduce income tax/national insurance and boost corporation tax – but not enough to make a difference to this analysis.

-

2This comes from the excellent OBR piece. Well worth a read

-

3The two big ones: (1) GOS is not the same as accounting profit, and in particular excludes depreciation (so the chart understates ETR), (2) the tax stats are for cash collected by HMRC in a tax year, which used to lag profits by around a year, and now mainly doesn’t – neither factor should affect the overall trend, but both will create/mask considerable noise. With some work they could be corrected.

-

4If anyone can point me towards pre-2000 tax rate data I’d be most obliged.

-

5If you have feedback on the quality of my incredibly amateurish coding then please do add comments on our official code feedback page here

-

6The OECD data only goes back to 2008

-

7Just promise me you won’t look at the US chart, because pass-through taxation (company profits taxed in the hands of owners/shareholders) means US corporate tax statistics can’t easily be compared with other countries’.

2 responses to “The myth of the corporate tax “race to the bottom””

No, this is incorrect. None of the above relates to the tax base of an individual company. The ONS chart shows the economy-wide effective tax rate, i.e. total corporate tax divided by total corporate profits (excluding financials and offshore oil/gas, who all pay a significantly higher rate).

The incorporation effect (increased CT; reduced IT/NICs) is real, but relatively small. Around £1bn. Was bigger when the corporation tax rate was 10% – perhaps as much as £3bn, but still not large enough to dent the trends shown above.

I really don’t think there is room for debate on this. The evidence is clear that corporate tax, as a % of GDP or a % of profits, has not been cut.

Dan, I think you are eliding the difference between the “tax base” of an individual company and the aggregate base of corporate profits taxed in the UK. An analysis of whether cutting the CIT rate reduces the revenues from CIT should take account of the relative size of that aggregate base. Your footnote 1 concedes that this base has grown, partly due to a rise in incorporation. This is likely to be partly driven by the reduction of the CIT rate below the individual income tax rate, as well as other tax advantages of incorporation. Your footnote says this is just “noise”, and makes no difference to the analysis, but I think it’s important not to confuse the individual company’s tax base with aggregate UK corporate profits. Cutting CIT rates may boost CIT revenue while reducing the revenue from other taxes.