In May, the Government announced the Energy Profits Levy – a windfall tax on UK oil and gas companies. It has two significant flaws, which together mean the tax will raise almost £5bn less than it could have done.

This post is an explanation and expansion of points I make in Panorama’s programme on the energy crisis, broadcast on 5 September (and reflects further thinking since I recorded the interview a few weeks ago). I’ve another post looking at how a more ambitious windfall tax could raise £30bn.

Flaw 1 – this windfall tax misses some of the windfall

The Energy Profits Levy was announced on 26 May 2022 and applies from 26 May 2022. For most taxes that wouldn’t be surprising. But for a windfall tax it’s odd, because windfall taxes are usually retrospective – i.e. taxing a windfall that’s already been made.

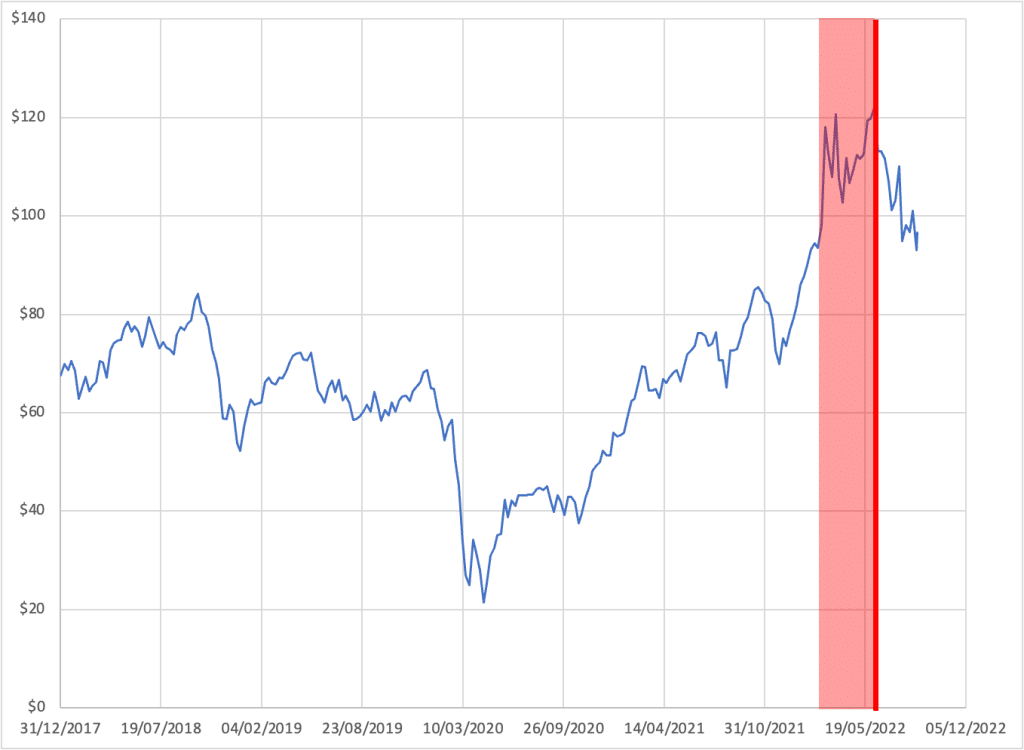

This chart at the top of this post shows the oil price over the last five years1Data from Yahoo Finance. A more serious analysis would probably be looking at natural gas futures pricing, but that’s way outside my expertise… this chart suffices for the basic point that the windfall tax kicks in well after the windfall starts – the shaded red section shows the oil price breaking $100/barrel, at the point of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The red line shows the point at which the windfall tax starts to apply… it’s clear that this windfall tax misses a large chunk of the actual windfall.

If the tax had applied from 24 February it would have raised an additional sum of approximately £1.5bn.2I estimate this by taking the £5bn yield the Government expects in its first ten months, and then pro-rating that across an additional three months.

Flaw 2 – the investment allowance is pure deadweight cost

The windfall tax is charged at 25% of oil and gas profits. So a company with £100m of windfall tax profits would pay £25m tax.

But the government was sensitive to claims that a windfall tax would deter investment, and so introduced an 80% allowance for capital expenditure and, in addition, a 100% first year allowance.

Many tax reliefs are introduced to encourage more of a Good Thing. Those reliefs always have a “deadweight cost” – the cost of giving relief to something that would have happened anyway, as well as a benefit (the Good Things that we will now get more of).

What are the benefits and deadweight costs of the investment allowance?

Calculating the benefit

The investment allowance works like this: if a company has oil and gas profits of £100m, and invests £50m in qualifying capital expenditure, it gets a deduction against its windfall tax profits of up to £90m (i.e. 180% of £50). So its windfall tax profits are reduced to £10m, and its tax only 25% of this – £2.5m.[/mfn]Needless to say, these are all highly simplified examples.[/mfn] That £50m investment has cost the company only £27.5m3i.e. because it is out of pocket £50m plus £2.5m tax; if it hadn’t invested at all it would have had £25m tax; hence the investment actually cost £52.5m minus £25m. It’s actually less than this once we take into account all the many, many, other reliefs against ringfenced oil/gas corporation tax, but I want to focus solely on the design of the windfall tax.

First thought: wow, what a fantastic incentive that is sure to generate lots of new investment!

Second thought: hang on, the windfall tax isn’t around for very long – it ends 31 December 2025. So for any oil and gas investment to be incentivised by the investment allowance, the project needs to move from drawing-board to breaking ground in 30 months. My understanding from industry contacts is that very few, if any projects will do this.

It’s even worse than that – 31 December 2025 is the “sunset date” – the tax will be phased out earlier if oil and gas prices return to “historically more normal levels”. A tax relief that lasts for an unpredictable amount of time is not a tax relief many people will be banking on.

These points suggest there will be little or no upside from the investment allowance – the only projects that will materially benefit from the investment allowance will be those that were already planned.

A more general point: giving 100% investment relief (aka “full expensing”) is a good idea, even an excellent idea, but it absolutely can’t be part of a temporary tax regime. And another important point: there is evidence that investment reliefs are ineffective in times of economic uncertainty.

Calculating the deadweight cost

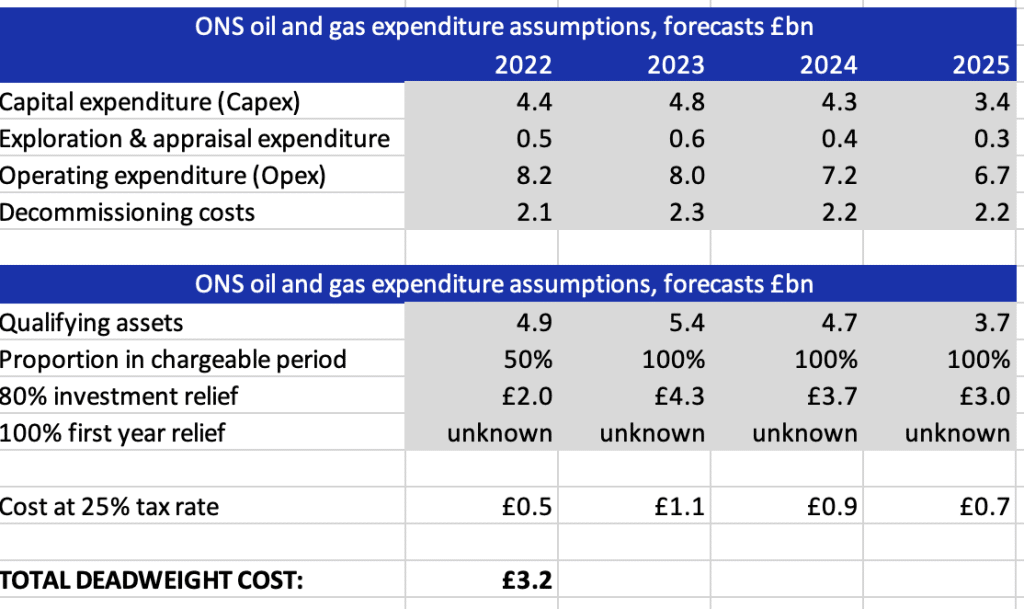

The deadweight cost is the cost of giving the investment allowance to investments that are already in the pipeline. We have a good idea of what the pipeline looks like, thanks to the ONS’s projections for North Sea capital expenditure (made prior to May 2022)4See here, and go to Supplementary fiscal tables – receipts and others, tab 2.14. We can pick out the qualifying items from this, and calculate the cost of giving them the 25% allowance:

This gives an estimate of the deadweight cost of £3.2bn. That will be a low-end estimate, because it ignores a number of factors, each of which would increase the actual deadweight cost:

- The calculation completely ignores the 100% first-year relief, as I have no data on the proportion of the capital expenditure which is first-year expenditure; any suggestions would be appreciated (although I expect the proportion will be small, given the long life of most oil/gas equipment).

- I ignore leasing expenditure, and this is not separately shown in the ONS forecast – will be an element of operating expenditure. This is likely a bigger effect. There is also an obvious avoidance route of recycling existing assets into leases to claim the allowance (although in principle HMRC out to be able to counter that).

- I’m not taking account of deferral effects – i.e. where investment planned for early 2022 was pushed back into late 2022 to benefit from the investment allowance. These are likely limited, as industry had little warning of the tax.

- Similarly, I don’t take account of acceleration effects, e.g. investment already planned for 2026 being moved up into 2025 to claim the relief – that will likely be more significant.

- Finally, there is now a large incentive to reclassify items so they benefit from the relief.

So, overall, it’s fair to say that the two flaws result in a loss of around £5bn of tax revenue.

-

1Data from Yahoo Finance. A more serious analysis would probably be looking at natural gas futures pricing, but that’s way outside my expertise… this chart suffices for the basic point that the windfall tax kicks in well after the windfall starts

-

2I estimate this by taking the £5bn yield the Government expects in its first ten months, and then pro-rating that across an additional three months

-

3i.e. because it is out of pocket £50m plus £2.5m tax; if it hadn’t invested at all it would have had £25m tax; hence the investment actually cost £52.5m minus £25m. It’s actually less than this once we take into account all the many, many, other reliefs against ringfenced oil/gas corporation tax, but I want to focus solely on the design of the windfall tax.

-

4See here, and go to Supplementary fiscal tables – receipts and others, tab 2.14

2 responses to “The £5bn flaws in the UK oil and gas windfall tax”

That doesn’t seem an alternative to the windfall tax; it’s an alternative to how the funds raised are used. You suggest a price subsidy. I suggest putting cash in peoples’ hands. The advance of the latter is that we can focus resources on those most in need, which is hard to do with a subsidy. A subsidy also means there is no price signal…

A windfall tax is a poor approach to this problem of high profits. A better idea is as follows:

1) regulate wholesale price of domestically produced natural gas

2) subsidize imported natural gas to the desired domestic price

3) cap prices of renewable and nuclear produced electricity at the new marginal cost of gas-generated electricity.

This approach puts cash straight back to all consumers rather than transiting through the government. The cost could be high but the alternative is disaster.