If we wanted to raise significantly more than the Government’s £5bn Energy Profits Levy, how would we do it?

This is a further explanation and expansion of points I make in Panorama’s programme on the energy crisis, broadcast on 5 September, and follows my previous post discussing two serious flaws in the Energy Profits Levy – the relatively modest “windfall tax” the Government introduced in May.

The politics

I’m not going to get into the rights/wrongs of windfall taxes, other than to note that the political case for a more ambitious tax may be hard to resist if energy companies make £170bn of “excess profits” over the next two years, when at the same time it seems increasingly likely that the Government is going to spend £18bn or even £29bn keeping energy prices down for consumers.

The design challenges

The big problem is: how do we define an “excess profit”? The apparent Treasury leak of the £170bn figure didn’t bother to say1Which is one reason to be suspicious of the leak, and of the figure.

It was relatively easy for the last two big UK windfall taxes.

- In the late 70s and early 80s there was a perception that the banks had made a windfall profit from low or zero interest deposit accounts, at a time when interest rates were at historic highs. So in the second Budget of the new Conservative Government, on 10 March 1981, the Chancellor introduced what was the “Special Tax on Banking Deposits”. This was a very simple tax, with the principal charging provisions fitting on one page. It simply took the average balance of zero-interest bank deposits held by banks during the last three months of 1980, and taxed that at 25% – so directly taxing the windfall, and raising approximately £400m.

Note the important common features: one-off taxes, applying to clearly identified windfalls, and doing so retrospectively. These are good design features which we should seek to copy. The retrospective element is counter-intuitive – normally we’d say retrospective taxation is undesirable, even wrong, but in this case retrospection is essential both to enable the windfall to be clearly identified, and prevent avoidance/distortions.

The difficult question in this case is: how do we identify the windfall?

Three sophisticated approaches that won’t work

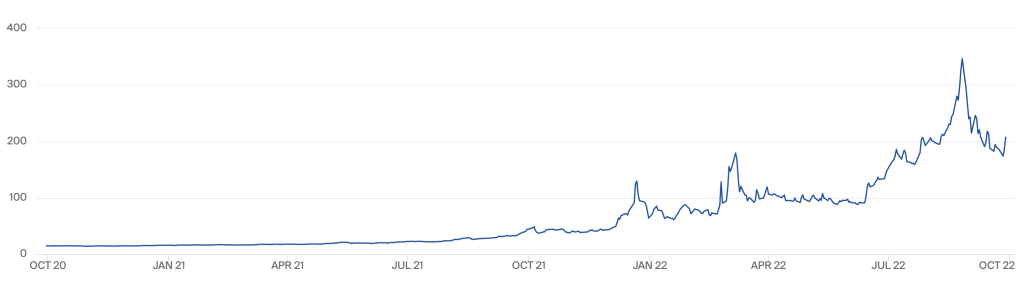

Here is the heart of the windfall, the European gas futures price:2Thanks to R for their help with this – the chart is from here

It’s this that feeds into electricity prices generally, because the marginal price of electricity is set by gas. There is an excellent explanation of this here.

In principle, we could calculate what energy company profits would have been in a parallel universe where energy prices hadn’t changed since January 2022. Then deduct that from the actual profits, and tax the difference. Fantastic, but for the minor detail that this is impossible – no complex business has systems/accounts that enable a calculation of this type to be made (i.e. because energy prices don’t go straight to the bottom line as revenue – energy prices are also a cost for most energy companies, and both costs and revenues are often hedged, energy is often sold on the basis of fixed prices, etc etc etc). If you ignore these complexities and just tax the immediate revenue impact of the increase in prices, then you end up with the Spanish windfall tax, which was something of a disaster.

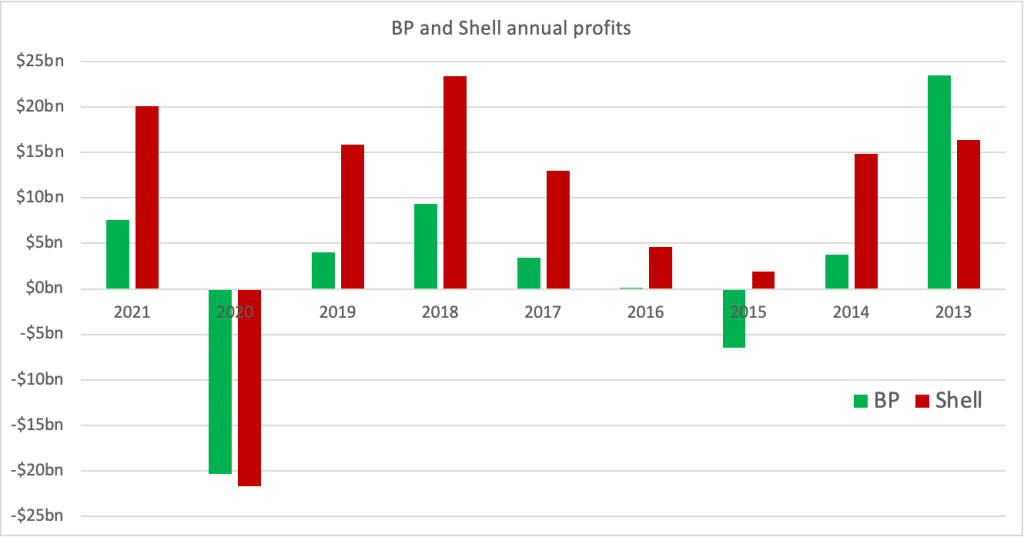

That suggests we need to look at profits, not prices, and apply some kind of revenue trend approach, for example saying that 2021 is the baseline profit, and any increase in 2022 is excess profit which we’ll tax. But that’s extremely random, and really just punishes companies who had a poor 2021. If Shell and BP go on to make identical profits in 2022, it can’t be right that we tax BP more, just because in 2021 Shell’s profit was higher.

Alternatively, we could follow the approach adopted by the various wartime excess profit taxes which looked at the average profit during a prior period. This was proposed as a way of taxing excess profits resulting from the pandemic, but to my mind is a bad fit for the energy sector, given the cyclical nature of energy company profits (exacerbated by their very poor performance in the 2020 pandemic):

I wouldn’t altogether discount this approach, particularly if we look across a very long period (say 20 years), but even then the result would be highly contingent on the precise period chosen (and where it cuts across the economic cycle), and therefore somewhat arbitrary. The extensive caselaw on the UK’s wartime excess profits duty (which shaped a surprising amount of modern tax law) is testament to quite how arbitrary and uncertain such taxes can be.

Other more sophisticated excess profit tax approaches have been proposed, e.g. categorising individual sources of profit, but they don’t seem very applicable to the problem we’re trying to solve.

A lovely idea that can’t work

Most of the large profits from the current crisis are being made elsewhere in the world – particularly in Gazprom, Saudi Aramco, and a plethora of US energy companies. Some people (okay, the Lib Dems) have suggested we tax those companies’ UK subsidiaries.

The difficulty with this is that in most cases all, or almost all, the profit is made outside the UK – so we have nothing to tax. Gazprom is an interesting exception – it has a UK trading arm with a reasonably significant market presence – and that’s probably why the Lib Dems name-check it specifically. The minor problem is that the company isn’t doing so well these days3And its profits were a fairly modest £300m even before it started running into trouble.

More radical ideas that are legally complex

Another suggestion has been to tax listed energy companies on their capital appreciation. This has a number of difficult legal issues, and in particular potential conflicts with tax treaties and EU law. I discuss this further here.

A simple approach that should work

So the best solution may be the simple one of imposing a special top-up tax on the profits of energy companies from 26 February 2022 to whenever it is that market prices settle down. I’d tentatively set out the following design features:

- The tax should be on the consolidated accounting profit of all UK-headquartered energy production/generation/trading companies, and the profit of UK subsidiaries of foreign-headquartered energy companies. Certainly not limited to the big two listed giants – Shell and BP – but to all large businesses in the sector – including nuclear, wind and solar generation4Amended to clarify that I am not just focussed on oil/gas.

- A properly fair and sophisticated tax would separate out the profits of energy generation companies in the group from other companies, and only tax the former. This leads to endless complexity and unfairnesses5See: the bank levy – not a model anyone should adopt, so this should be a rough and unsophisticated tax that simply applies to the entire consolidated group profit of groups that make a majority of their profit from energy generation or trading, or oil/gas extraction.

- The tax should be retrospective, introduced only after prices return to normal. The basic form of the tax (a tax on global accounting profit6That means, for example, that the usual tax rules that exclude gains/losses on sales of subsidiaries wouldn’t apply, which I think is the correct result here. Imposing a windfall tax on BP that ignores its very real Rosneft losses would be unfair) would be announced now, together with an indication of the target revenue yield, but little more in the way of details. That minimises avoidance and other distortions, and enables the final form of the tax to fit with the windfalls that have actually been made.

- There would need to be large penalties for any company or individual seeking to evade7I think I do mean “evade” here and not “avoid” paying the tax by extracting profits in advance of the windfall tax, leaving no cash for HMRC to collect.

- We should consider taxing companies global profits, not just UK profits. We don’t normally do this – but that’s not because it’s a high point of principle… it’s because foreign profits are normally taxed in other countries. If other countries aren’t taxing excess profits, we shouldn’t feel shy about taxing them ourselves. And if other countries do introduce similar taxes to tax excess profits, those taxes should be creditable against the tax of UK-headquartered companies.

- Why consider taxing foreign profits in this case? Because I fear that the UK profit would not be a large enough tax base to raise the necessary sums. If that is wrong, that is excellent – it is problematic to tax foreign profits, and preferable not to do so. The great thing about a retrospective windfall tax is that we should know with reasonable certainty what the tax base looks like at the point that the tax is drawn up, and it is at this point that such decisions should be taken.

- The other pragmatic reason not to tax UK companies on their foreign profits is that it incentivises businesses to relocate. Relocation risk would be reduced if other countries introduced similar taxes (as seems likely). However, the critical element is for the Government to make a credible promise that there would be no repeat of the tax (just as there was in 1981 and 1998; these promises were kept).

If the actual windfall profit ends up being around the supposed leaked Treasury figures, then it’s not unrealistic to think such a tax could potentially raise £30bn over two years.

However, it’s important to stress that we shouldn’t start taxing a windfall before a windfall has actually been made. Right now, BP and Shell had a very good Q2, and a decent Q1 (ignoring BP’s huge loss from the forced sale of its Russian business8I would allow such losses to be deductible in the proposed windfall tax, as they’re part of the IAS consolidated accounting profit – but I can see a case for excluding them, given that companies could control the timing of disposals to avoid tax. One option would be to tax/relief gains/losses from 26 Februrary 2022 up to the date the tax is announced, but not afterwards). Let’s see what happens next. When it comes to windfall taxes, there’s no time like the past.

-

1Which is one reason to be suspicious of the leak, and of the figure

-

2Thanks to R for their help with this – the chart is from here

-

3And its profits were a fairly modest £300m even before it started running into trouble

-

4Amended to clarify that I am not just focussed on oil/gas

-

5See: the bank levy – not a model anyone should adopt

-

6That means, for example, that the usual tax rules that exclude gains/losses on sales of subsidiaries wouldn’t apply, which I think is the correct result here. Imposing a windfall tax on BP that ignores its very real Rosneft losses would be unfair

-

7I think I do mean “evade” here and not “avoid”

-

8I would allow such losses to be deductible in the proposed windfall tax, as they’re part of the IAS consolidated accounting profit – but I can see a case for excluding them, given that companies could control the timing of disposals to avoid tax. One option would be to tax/relief gains/losses from 26 Februrary 2022 up to the date the tax is announced, but not afterwards

One response to “How to design a £30bn windfall tax on the energy sector”

Interesting and valuable analysis, thanks – I was alerted to your blog from Financial Times comments: https://www.ft.com/content/1801fa19-b17b-454e-ba2f-41e82caaef19?commentID=21990115-9391-472c-b980-3bfe0fbebec2 .